ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

18TH & 19TH CENTURY MARKING OF LINEN

– Garments and Bedlinen kept in a Museum Collection

In larger homes containing a considerable quantity of linen and underclothes that needed to be kept under control, some form of sorting system would be used to ensure that each item could be returned to its correct place after washing, mangling and ironing. Garments would be numbered, often with the owner’s initials or name added. The decorative and historical value – remembering the year one particular item was purchased, inherited or stitched – must additionally have been valuable for all social strata of society. This study will give a few examples from the Whitby Museum collection illustrating the traditions of marking linen in tiny, beautiful stitching or with clear hand-writing in indelible ink, dating from 1710 to 1850.

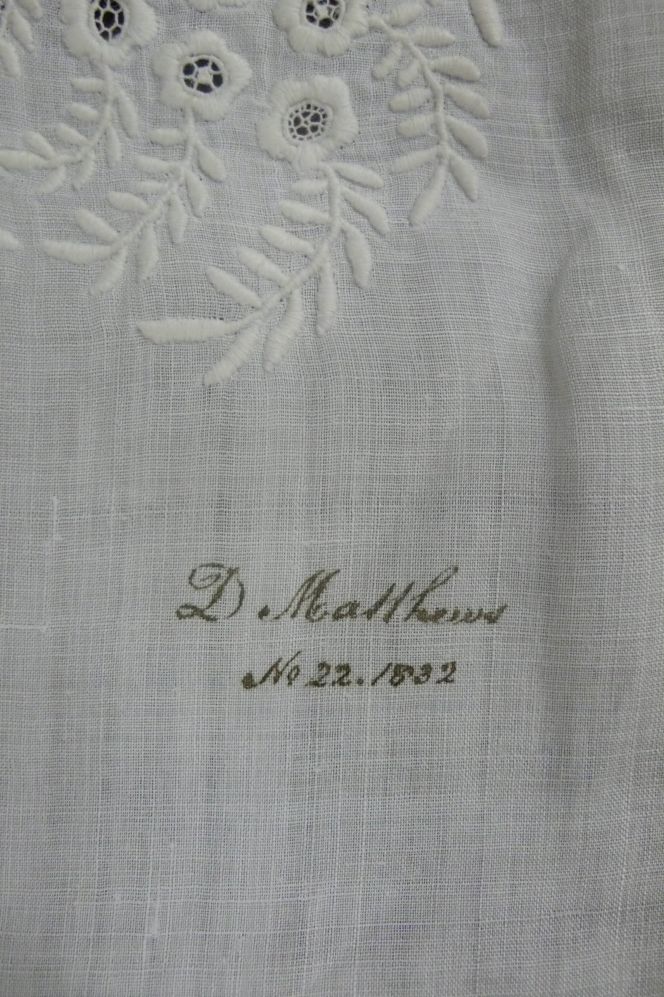

This piece of embroidery marked in ink, featuring satin stitch and drawn thread work sewn on the finest cotton fabric to decorate a handkerchief. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, unnumbered at time of research). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

This piece of embroidery marked in ink, featuring satin stitch and drawn thread work sewn on the finest cotton fabric to decorate a handkerchief. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, unnumbered at time of research). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Marking could either be done in embroidery, usually using cross-stitch or back-stitch, or often with a pen and indelible ink, a quicker way of inscribing the necessary information. Research has uncovered two good examples of the second type. The handkerchief illustrated above is made in finest quality cotton with drawn thread-work and satin stitch, which has been marked with pen and ink ‘D. Matthews No 22. 1832’, while a pair of machine-knitted long stockings in finest quality unbleached cotton has been marked ’25. Lf.C.J. 1850’.

Apart from their year of origin, both these textiles carry a number that reveals that the wearer owned a large quantity of garments that needed to be numbered for correct sorting so that nothing would be lost. This suggests a home with a housekeeper or, at the very least, several servants whose duty was to store the completed laundry in the right places – free of moth, damp and dust – in the general linen cupboard or in the personal drawers of the relevant member of the family.

![The Whitby collection includes a nightgown embroidered in white ‘VR 24’ with a crown. This garment, known as ‘Queen Victoria’s nightdress’, is said to have been used by Victoria in 1834 on a visit to Whitby before she became queen. There is written evidence that ‘Princess Victoria went up to the West Pier lighthouse in 1834, and visited the Old Museum [by Pier Road] and signed her name in the visitors’ book the same day.’ But it must be noted that the letters (VR = Victoria Regina) could not have been embroidered until after Victoria became Queen in 1837. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS58). Photo: Viveka Hansen.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-marking-of-linen-1-664x645.jpg) The Whitby collection includes a nightgown embroidered in white ‘VR 24’ with a crown. This garment, known as ‘Queen Victoria’s nightdress’, is said to have been used by Victoria in 1834 on a visit to Whitby before she became queen. There is written evidence that ‘Princess Victoria went up to the West Pier lighthouse in 1834, and visited the Old Museum [by Pier Road] and signed her name in the visitors’ book the same day.’ But it must be noted that the letters (VR = Victoria Regina) could not have been embroidered until after Victoria became Queen in 1837. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS58). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

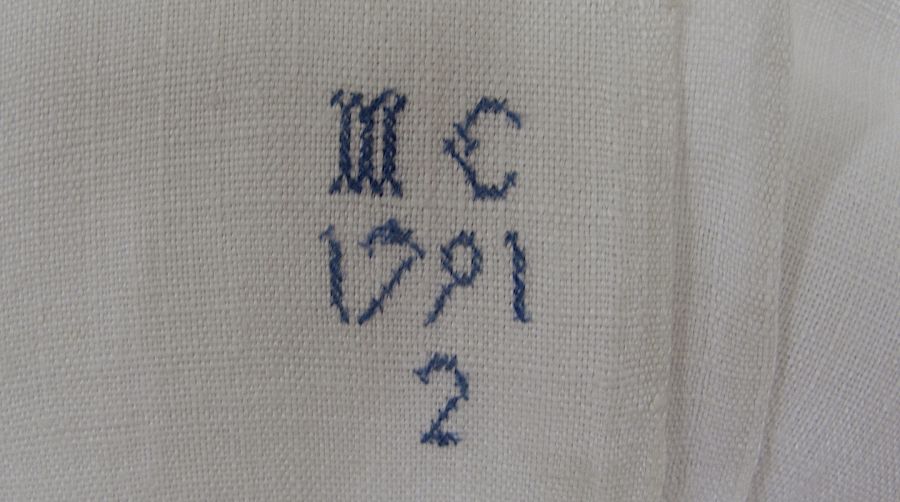

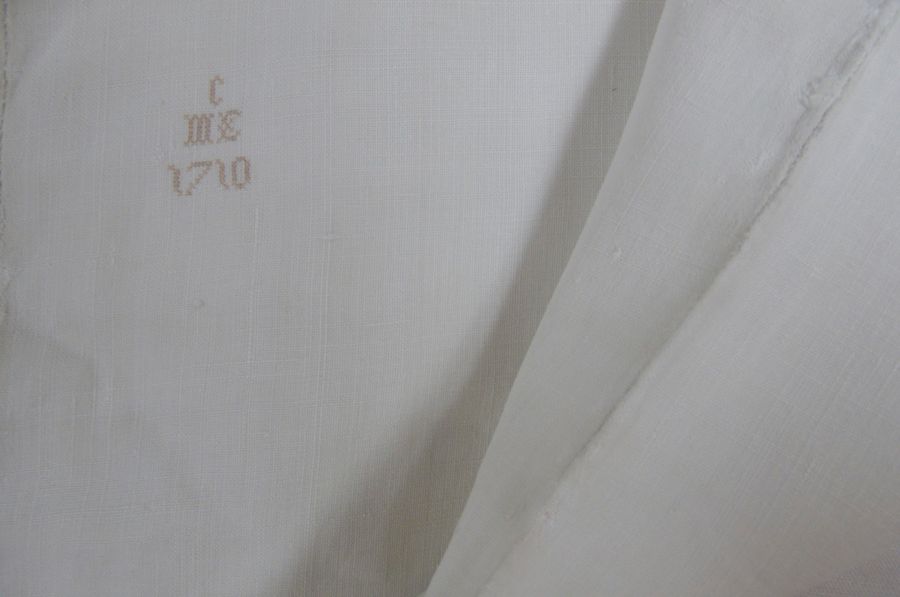

The Whitby collection includes a nightgown embroidered in white ‘VR 24’ with a crown. This garment, known as ‘Queen Victoria’s nightdress’, is said to have been used by Victoria in 1834 on a visit to Whitby before she became queen. There is written evidence that ‘Princess Victoria went up to the West Pier lighthouse in 1834, and visited the Old Museum [by Pier Road] and signed her name in the visitors’ book the same day.’ But it must be noted that the letters (VR = Victoria Regina) could not have been embroidered until after Victoria became Queen in 1837. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS58). Photo: Viveka Hansen.However, household linen was never marked with pen and ink back in the 18th century, when items would be marked with a simple cross-stitch monogram including initials and the year. Two interesting examples of this survive on hand-woven linen sheets, one with the very early date ‘C ME 1710’ while the other comes from late in the same century: ‘MC 1791 2’ – see images below. Both these sheets have a central seam, proving that they were produced on hand looms that were unable to accommodate the full width of the sheet. Besides, both selvedge and the linen itself exhibit the kind of slight structural unevenness not found after the introduction of machine weaving, which would ensure a more consistent, if less individual, result.

Well-preserved linen sheet, marked ‘C ME 1710’. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS18). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

Well-preserved linen sheet, marked ‘C ME 1710’. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS18). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 308-09 & 322-25).

- Whitby Museum, Textile & Costume Collection (studies of a multitude of linen sheets, linen garments etc and the frequency of marking).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE