ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

18TH CENTURY EAST INDIA TEXTILE TRADE

– A Study of Imported Merchandise to Sweden

A few 18th century East Indian textiles, in a Swedish museum collection, were evidently brought back to Europe via the British East India Company and probably sold in London to visiting Swedish individuals. These sought-after commodities used for fashionable clothing and interior textiles, were later on or close to the purchases in time taken back home for their own family use or to be resold. Other links to similar extensive trades are closely linked to Carl Linnaeus’ so-called seventeen apostles, whereof some had direct contact with several of the East India trading companies which imported cloth for the European market. Travel journals and correspondence from these naturalists’ long-distance voyages, while working as either ships’ chaplains or surgeons onboard or assisting botanists – include various information about silks from Canton [Guangzhou], cotton from Surat and much more, which will also be closer observed in this essay.

The European factories “Thirteen Factories”, in a line at the port of Canton, are depicted here on a Chinese oil on canvas circa 1820, eight factories were situated at the same location already 70 years earlier when Carl Linnaeus’ apostles visited the region. The Swedish factory can be seen behind the third flag on the right, where East India Company’s goods was collected prior to the return voyage to Sweden, including the many valuable fabrics, packed with particular care in chests so as best to be protected against weather and wind as well as harmful creatures onboard during the long sea voyage. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons).

The European factories “Thirteen Factories”, in a line at the port of Canton, are depicted here on a Chinese oil on canvas circa 1820, eight factories were situated at the same location already 70 years earlier when Carl Linnaeus’ apostles visited the region. The Swedish factory can be seen behind the third flag on the right, where East India Company’s goods was collected prior to the return voyage to Sweden, including the many valuable fabrics, packed with particular care in chests so as best to be protected against weather and wind as well as harmful creatures onboard during the long sea voyage. (Courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons). Three of Linnaeus’ former students travelled as ship’s chaplains with the Swedish East India Company and made textile observations in their journals. Whereof Pehr Osbeck’s journal from 1750-52 has the most detailed notes, describing the various stages of weaving, in which he had very much wanted to take part, but was partially prevented by restriction of movement and other obstacles for Europeans in the Canton area. Other interests include documentation on looms, the importance of the manufacturers, orders of fabric at arrival, the trade in fabrics onboard ships, lists of cotton and silks, etc. His contemporary, Olof Torén, also stressed the significance of fabrics within the East India trade at Canton and also from Surat in a series of letters to Linnaeus (1750-52). In addition, he described the reeling of silk and spinning of cotton at Canton and mentioned that the nankeen fabrics were considered to be the very finest of all. The first of the travelling apostles, Christopher Tärnström, who never reached Canton, nonetheless made several notes in his journal in 1746 on the East India trade. He bought, for example, pieces of cotton at Pulo Condore [Côn Són Island], which were thought to be of extremely good value, and mentioned the high-ranking officers’ private trading in East Indian fabrics of various materials along with Swedish linen fabrics. Such fabrics of different origins were sold wherever it was most advantageous, which might mean that fabrics from a previous voyage could be sold in ports on the next outward voyage. Moreover, like Torén, he described the nankeen qualities as most highly valued and worn by the prominent inhabitants of Pulo Condore during his stay in the area.

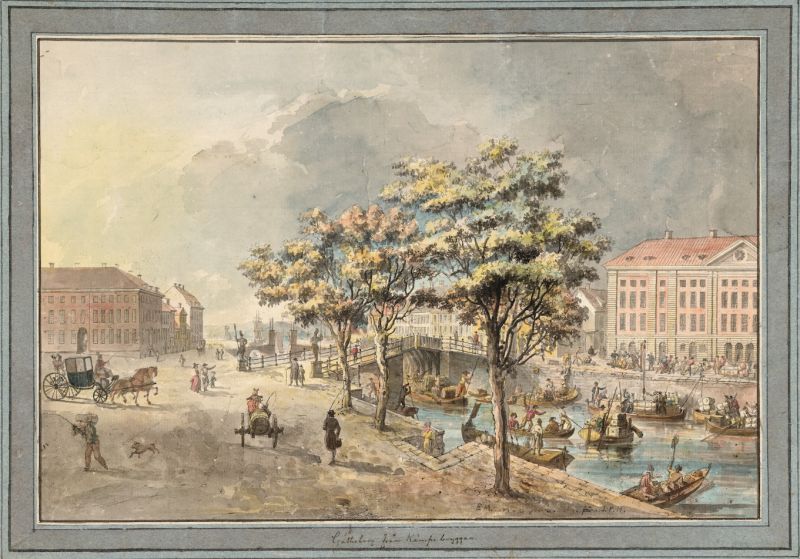

This graphic water-colour by Elias Martin from 1787 shows the bridge Kämpebron and the canal outside the Swedish East India Company building (constructed 1747-1762) in Göteborg. Although it was painted a few decades after the East India voyages of the Linnaeus Apostles, the trade using canal boats to transport goods from ships further away in the harbour and unloading goods at the Factory can be assumed to have looked fairly similar. (Courtesy of: Göteborgs Stadsmuseum…).

This graphic water-colour by Elias Martin from 1787 shows the bridge Kämpebron and the canal outside the Swedish East India Company building (constructed 1747-1762) in Göteborg. Although it was painted a few decades after the East India voyages of the Linnaeus Apostles, the trade using canal boats to transport goods from ships further away in the harbour and unloading goods at the Factory can be assumed to have looked fairly similar. (Courtesy of: Göteborgs Stadsmuseum…).The long-distance travelling naturalists of later dates during the 1760s and 1770s also provided repeated examples of notes on that textile trade. The journal writers in Daniel Solander’s group on James Cook’s first voyage demonstrated the Dutchmen’s considerable trade in fabrics from Savu and Batavia, while during his time in Africa, Anders Sparrman described the Cape as an important anchorage for that trade, with European as well as Asian fabrics being sold and bought. Carl Peter Thunberg, too, mentioned the ideal situation of the Cape for trade in fabrics, for example, in both directions for the East India ship. There were restrictions, however, on what merchandise could be traded, the East India Companies having the monopoly on certain fabrics, and contraband, therefore being a widespread occurrence. He also noted that Chinese and Javanese textile traditions were not only spread through trade in the respective countries but also through the fact that Chinese and Javanese people were themselves settled and living in the Cape; in addition, he noted the busy trade in cotton and silks in Batavia. His time in Japan also gave rise to repeated notes to do with trade. The Japanese mainly traded with the Dutch East India Company, China and Korea, but the country was otherwise inaccessible to outsiders. The fact that Thunberg had the possibility to take part in the journey to Jedo [Tokyo] as a “European observer” gave him unique insight into textile traditions, trade etc. Finally, he noted that Ceylon’s [Sri Lanka] trade in Indian muslins consisted of the finest and thinnest fabrics he had ever seen during his nine-year-long journey. Much of Carl Linnaeus’ Swedish observations during his provincial tours of the 1740s were, moreover, indirectly linked to the East India trade, as regulations on the restriction of Swedish imports were largely directed against the exclusive fabrics which entered the country via that lucrative Swedish trade.

The fine cotton quality of ikat weaving used for this full-length 18th century banyan with matching waistcoat, has been identified by historian Lena Rangström as originating from India. Due to the included British East India Company bale mark (see image below), it is evident that the fabric or maybe even the ready made garments had been exported via this trading company from India to Britain. In some unknown way the banyan and waistcoat ended up in Sweden, probably via some well-to-do visitor to London during the 1770s and were brought back on his return journey home. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0065412).

The fine cotton quality of ikat weaving used for this full-length 18th century banyan with matching waistcoat, has been identified by historian Lena Rangström as originating from India. Due to the included British East India Company bale mark (see image below), it is evident that the fabric or maybe even the ready made garments had been exported via this trading company from India to Britain. In some unknown way the banyan and waistcoat ended up in Sweden, probably via some well-to-do visitor to London during the 1770s and were brought back on his return journey home. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0065412). Close-up detail of the bale mark VEIC (Honourable East India Company/HEIC), preserved on the banyan illustrated above, dating ca 1770s to 1790s. The ‘V’ appears to originate from ‘United’ as the Company also was named ‘United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies’ (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0065411).

Close-up detail of the bale mark VEIC (Honourable East India Company/HEIC), preserved on the banyan illustrated above, dating ca 1770s to 1790s. The ‘V’ appears to originate from ‘United’ as the Company also was named ‘United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies’ (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0065411). Interestingly, this printed calico, used as the lining on an 18th century Indian palampore originating from the Coromandel Coast, includes the very same mark. This small bale mark is an additional proof for that such fine cottons, imported via the British East India Company, at times ended up in well-to-do Swedish ownership. Hundred years or more later, some of these textiles were donated or sold to museum collections like this example. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0025544).

Interestingly, this printed calico, used as the lining on an 18th century Indian palampore originating from the Coromandel Coast, includes the very same mark. This small bale mark is an additional proof for that such fine cottons, imported via the British East India Company, at times ended up in well-to-do Swedish ownership. Hundred years or more later, some of these textiles were donated or sold to museum collections like this example. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0025544).At least three names were commonly used for the British trading company: the East India Company (EIC) or British East India Company or Honourable East India Company (HEIC). Contacts with Swedish merchants, individuals linked to the Swedish East India Company, other Swedes on East India travel, meetings in harbours along the route or visits in England were obviously intertwined in a multitude of ways during the second half of the 18th century. Global cultures spread at an increasing speed due to those shipping enterprises with their commercial trade and Imperial expansion alike, giving already desired fabrics – one of the most popular merchandise to transport – in the European market even more desirable and accessible for more than the well-to-do. This ongoing consumer revolution often gave owners and shareholders large profits, at the same time as luxury wares became increasingly fashionable.

Despite all revenues for some, existing monopolies and restrictions opened up for “alternative” trades. A set of complex sumptuary laws in some European countries additionally set rules for which fabrics were allowed to be traded, sold or resold. Sweden, among others, had several such restricting laws over the century, which set out strict rules and limits for the way people of different positions in society were to dress and furnish their homes. A total ban on imports of textiles of finer sorts was therefore introduced in November 1756, for instance, and that covered not only costly silks from East India but included even finer woollen fabrics and wool yarn, which for a long time had traditionally been imported from a number of European countries. The restrictions were intended to improve the potential of the domestic manufacturers, but thanks to Sweden’s long coastlines, the bans opened up new possibilities for smugglers instead. However, such laws were revoked later on by Gustav III during his reign from 1772 to 1792, making it easier to import what luxury goods one desired. All fine East Indian silks and cotton qualities on the market overall gave positive influences and large profits for the European and Chinese traders, but from the perspective of some controlled areas, it was often another matter. One negative effect among many for local citizens may be noted from mid-18th century Bengal in India, where the population came to live under real hardship, poverty and famine due to new extended British land taxes, wars and expanding colonial settlements.

This squared piece of chintz or hand-painted Indian calico is a third example of an 18th century cotton fabric kept at the Nordic Museum, with the bale stamp VEIC at the back, that is to say another historical link to the Honourable East India Company. Judging by earlier folding and cut of corners, it must have been used for upholstering of a small chair and the fabric was carefully removed to be saved, possibly due to its beautiful design. Unknown original owner in Sweden (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0025613).

This squared piece of chintz or hand-painted Indian calico is a third example of an 18th century cotton fabric kept at the Nordic Museum, with the bale stamp VEIC at the back, that is to say another historical link to the Honourable East India Company. Judging by earlier folding and cut of corners, it must have been used for upholstering of a small chair and the fabric was carefully removed to be saved, possibly due to its beautiful design. Unknown original owner in Sweden (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum…NMA.0025613).This textile subject is very wide-ranging and has been written about a lot. Still, as far as I know, which was emphasised in my publication in 2017, there is no in-depth collected study of all the European East India Companies’ trade in textiles. The observations by Carl Linnaeus’ apostles do, in any case, provide a good contemporary insight into the Swedish and the Dutch East India Companies with detailed descriptions of fabric qualities, trading conditions, production, demand, smuggling, contraband, officers’ possibilities versus those of the rest of the crew to buy cloth etc. However, it is clear that the cotton spinning, silk reeling and cloth weaving at Canton and its environs were some of the most crucial branches of the trade, crafts which must have been continued on an industrial scale in domestic settings, taking into account the highly substantial trade with Sweden and other European companies, at times together with other East India ports, over several centuries.

Sources:

- Göteborgs Stadsmuseum, Sweden (Göteborg City Museum): water-colour by Elias Martin no. GhmB: 12971.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 301-02, 395-96 & individual chapters for mentioned naturalists).

- Hellman, Lisa, Navigating the foreign quarters – Everyday life of the Swedish East India Company employees in Canton and Macao 1730-1830, Stockholm 2015.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974.

- Peck, Amelia, ed., Interwoven Globe – The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, New York 2013.

- Rangström, Lena, Modelejon – Manligt Mode 1500-tal, 1600-tal, 1700-tal, Stockholm 2002 (p. 263).

- Söderpalm, Kristina, ed., Ostindiska Compagniet – Affärer och Föremål, Göteborgs Stadsmuseum 2003.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden (DigitaltMuseum, information on catalogue cards for one garment & two fragments originating from trade via the British East India Company).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE