ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

18TH CENTURY SILK DYERS

– in London

A selection of 68 trade cards and bill-heads from 1703 to 1818 demonstrate some fascinating facts about the dyers and cleaners of London. To regard oneself as silk dyer dominated, whilst secondary titles were scarlet dyer, scourer or cleaner of various garments, dyer of cotton/calico or woollen fabrics. These randomly preserved trade cards and receipts also give some idea of preferred colours by the customers and all other services that were available in such establishments. Additionally, this case study will include some information about the most used and desired natural dyes – in a time when neither synthetic dyes nor dry-cleaning with non-water-based methods were invented.

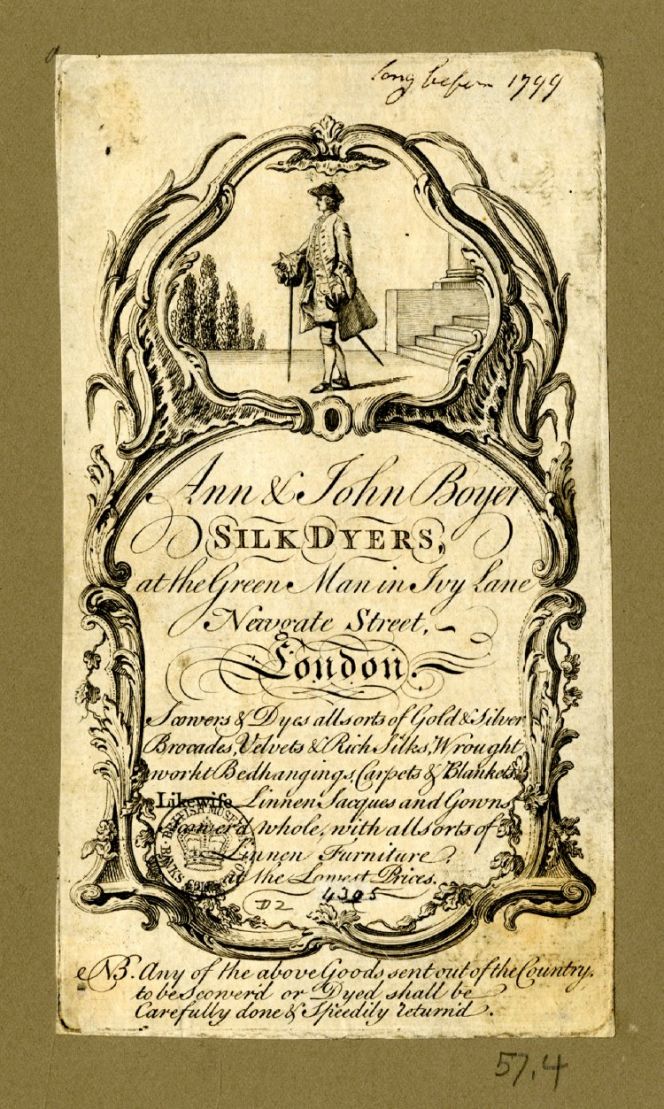

This Silk Dyer’s trade card from “long before 1799” includes information of various services. Two details may be noticed; firstly that wife and husband alternatively sister and brother, Ann & John Boyer were the owners. All the other cards are stating male silk dyers only. Secondarily that these traders assisted customers abroad, possibly from the English colonies where it was difficult to find such services. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 57.4. (Collection online).

This Silk Dyer’s trade card from “long before 1799” includes information of various services. Two details may be noticed; firstly that wife and husband alternatively sister and brother, Ann & John Boyer were the owners. All the other cards are stating male silk dyers only. Secondarily that these traders assisted customers abroad, possibly from the English colonies where it was difficult to find such services. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 57.4. (Collection online).A search for “trade card dyer” in the British Museum’s collection online returned 68 results, and all of these traders worked in London. Even if 50 establishments, or 75%, were named “Silk dyer”, – these professionals often took care of other materials like cotton, wool and linen garments or interior textiles. For example, William Marsh, who was a Silk-dyer at the Rainbow & Bush in Brook Street Holborn London, stated in 1802: ‘Dyes all Sorts of Silks, Silks; Worsted and Cotton Furniture, Blankets and Quilts’. Additionally, ‘Mens Cloaths Scower’d [scoured] Wet or Dry’. That is to say that clothes were scrubbed clean before the invention of non-water-based cleaning processes in the 19th century. The remaining 18 dyers described their occupations as follows:

- Dyer – 4

- Dyer and scowerer/cleaner – 7

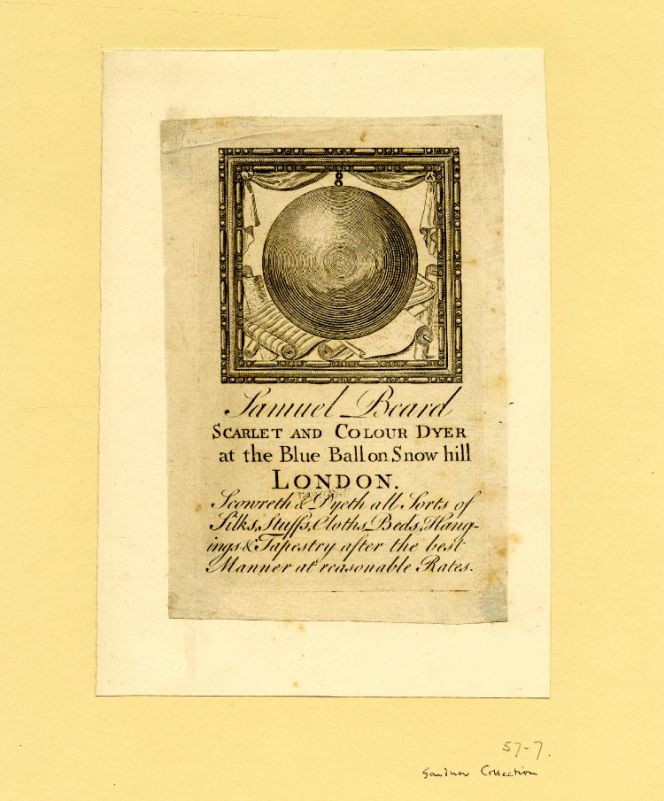

- Scarlet & colour dyer – 1

- Silk & scarlet dyer – 1

- Silk calico/cotton & woollen dyer – 2

- Silk dyer & calico glazer – 1

- Silk dyer, calenderer & glazer – 2

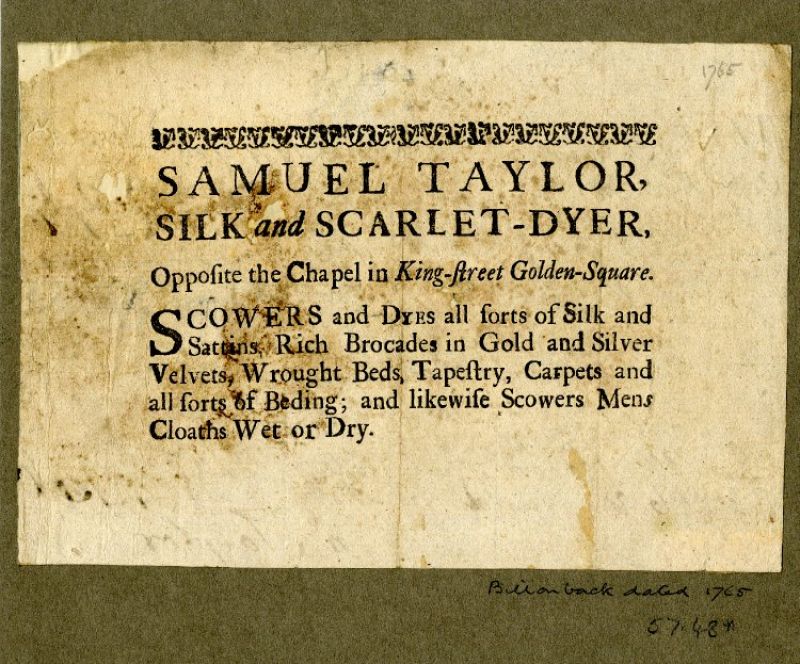

Samuel Taylor, silk and scarlet-dyer described the services he offered to customers in the mid 1760s at Kings street, Golden Square in Soho, London. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.48. (Collection online).

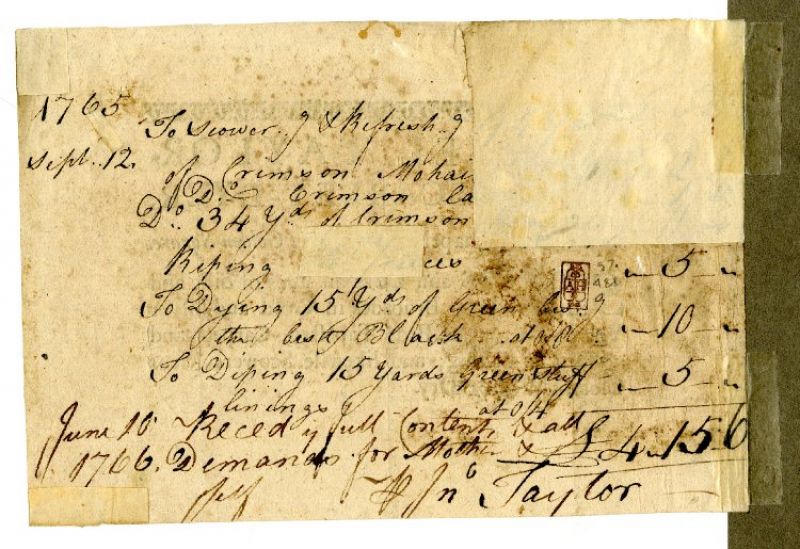

Samuel Taylor, silk and scarlet-dyer described the services he offered to customers in the mid 1760s at Kings street, Golden Square in Soho, London. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.48. (Collection online). At the back of this trade card (above), various goods were listed in 1765 and 1766 giving evidence for that this dyer among other services dyed cloths etc in ‘crimson’, ‘best black’ and ‘green stuff’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.48.+ (Collection online).

At the back of this trade card (above), various goods were listed in 1765 and 1766 giving evidence for that this dyer among other services dyed cloths etc in ‘crimson’, ‘best black’ and ‘green stuff’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.48.+ (Collection online).Even if this selection of documents is too small to prove or explain fluctuations in the dyer’s trade in London, it gives a brief view of such businesses. Twenty-two of these cards are undated, but in general, all trade cards and receipts originate from the 18th century and up to the 1820s. The dated examples may be divided into the following time periods, showing the quantity within each period:

- 1703-1740s – 4

- 1750s-1760s – 8

- 1770s-1780s – 13

- 1790s-1800s – 17

- 1810s-1820s – 4

A multitude of services were additionally listed on these cards, whilst textiles of all materials could either be dyed, cleaned or both. For instance, woven textiles such as brocades, blankets, bombasins, calicoes, carpets, Genoa damask, mantuas, mohair fabric, paduasoys, satins, shagreens, tabbies, velvets and worsted camblets. But an array of other specialised work was also available for dyeing, thorough cleaning or other services; here are some examples:

- Calenders and presses works in the best manner.

- Clean and dye all sorts of furniture.

- Cleaned and glazed linen gowns without taken to pieces.

- Cleaned wet or dry: tapestry, hangings, bed cloath, cloaks & coats etc.

- Cleans gold and silver brocades.

- Dye black.

- Embroidery darned.

- Fancy waistcoats cleaned.

- Linen of all kind dyed.

- Norwich crapes dyed.

- Restorer of all kind of silver and gold embroideries.

- Silks and stuff.

- Silk and worsted stockings cleaned and dyed.

- Takes all manner of spots and stains.

- Tambour embroidery cleaned.

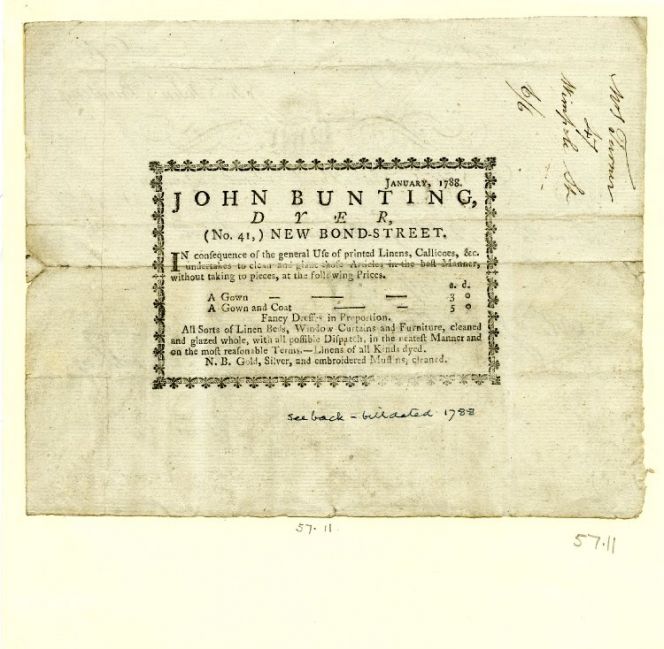

The dyer John Bunting at New Bond-Street was unusual as his work concentrated on printed linens and calicoes in the dyeing and cleaning business – some prices and other services are also included on his trade card dated 1788. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.11. (Collection online).

The dyer John Bunting at New Bond-Street was unusual as his work concentrated on printed linens and calicoes in the dyeing and cleaning business – some prices and other services are also included on his trade card dated 1788. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.11. (Collection online).A brief description of the complex process of natural textile dyes includes that some sources of dye were readily available, especially for yellow and brown, since these colours could generally be prepared from plants that grew locally. The best yellow dyes came from weld or mignonette Reseda luteola, chamomile Anthemis tinctoria, saw-wort Serratula tinctoria, silver birch Betula alba, and heather Calluna vulgaris. Mosses and lichens were usually used to make various brown barks (oak often preferred).

Traditionally, blue had been obtained from woad Isatis tinctoria grown in England, but even before 1700, this generally had to compete with imported indigo (a number of varieties of indigofera). For a long time, indigo was the dye imported in the most significant quantities, both by the British Empire and the other sea-going nations of Europe. The indigofera came from a wide range of places in America, the West Indies, India and Africa, with Bengal in India the place preferred by the British as the source for indigo at the end of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries. This was a valuable source of dye that could be picked, dried, worked, compressed and packed in chests to be transported to Europe.

This 18th century trade card illustrates the only establishment specialised as a ‘Scarlet and Colour Dyer’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.7. (Collection online).

This 18th century trade card illustrates the only establishment specialised as a ‘Scarlet and Colour Dyer’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.7. (Collection online).Orchella or archil, a source for popular red-lilac or blue-violet colours, was a lichen imported mainly from the Canary or Cape Verde Islands. But the best and most durable red dyes came from imported madder Rubia tinctoria which reached England mainly from Smyrna, Leghorn (Livorno) and Trieste. Two alternatives for red were Lac Dye, shipped from India, or strongly coloured carminic acid derived from the cochineal scale insect Coccus cacti. Lac Dye contains a deep red colouring agent. The scale insect cochineal originally came from South America via Spain, but was also freely cultivated in plantations in the Canary Islands – after the period (1830s) discussed in this case study – because of the dye’s huge popularity in Europe.

Greens could only be made by first dyeing yellow and then blue. Dyeing black or grey was the most difficult of all, since no plant naturally provides black or blackish dye. So, the dye normally used for brown had to be supplemented with large quantities of iron vitriol and galls, which often damaged the textile material, making it brittle. There were other methods that involved combining sufficient quantities of red and blue, whilst this was an expensive way of obtaining dark colours and so seldom used, but may have been used by professional dyers in London where customers were in the position to pay for such services. In general, the dyeing of cloth and yarn involved various degrees of costliness and hence varying status, with red, green and blue nearly always requiring an expensive outlay on imported dyes and frequently complicated dyeing methods.

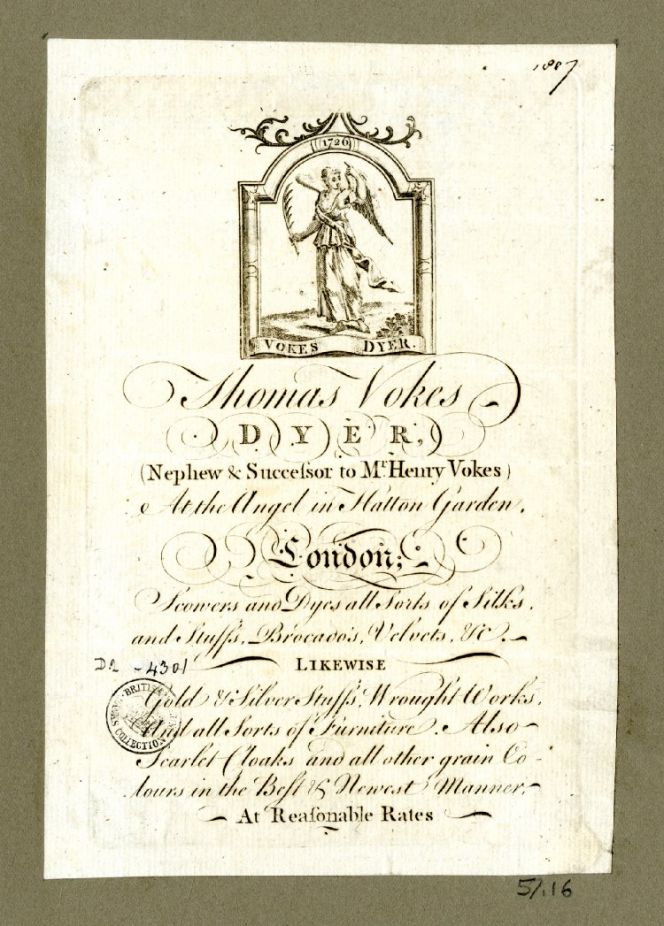

‘Vokes Dyer’ was founded in 1726 according to this trade card from 1807. Beside the long-lived family business’ services of cleaning and dyeing exquisite materials of gold, silver, brocades and velvets it may be noted their speciality for dying red was stated as: ‘Scarlet Cloaks and all other grain Colours in the Best & Newest Manner’. The word ‘grain’ in this context interestingly referred to kermes or cochineal. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.16. (Collection online).

‘Vokes Dyer’ was founded in 1726 according to this trade card from 1807. Beside the long-lived family business’ services of cleaning and dyeing exquisite materials of gold, silver, brocades and velvets it may be noted their speciality for dying red was stated as: ‘Scarlet Cloaks and all other grain Colours in the Best & Newest Manner’. The word ‘grain’ in this context interestingly referred to kermes or cochineal. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 57.16. (Collection online).A few other colour studies of the trade cards may finally be concluded with some notes of greens, reds and blacks – all costly colours to dye.

- Green silks etc on a receipt from 1790, Taylor, Silk dyer, at Maddox Street near Hanover Square.

- Dyes Scarlet, Crimson Rose Colour & Pink, 1775, Joseph Kettlewell.

- Dyed Crimson (on receipt 1755), Scowers and dyes all sorts of silks, James Hummerstone.

- Dying a lute black (on receipt 1763), William Houghton, Silk dyer.

- Dying the crimson curtains crimson, 1765 on receipt, Silk dyer Valentine Cole.

- Dye scarlet dyes to perfection, undated, Hugh Anderson Somerset House.

Sources:

- British Museum, Collection Online (Search words: ‘trade cards dyer’).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 290-92).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE