ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

18TH CENTURY WEAVERS IN LONDON

– a Case Study of Trade Cards and Bill-heads

A small selection of mostly undated 18th century trade cards and bill-heads give some enlightening facts of weavers in London. Due to observations learned from my earlier studies of trade cards linked to textile occupations, these randomly preserved documents indicate that it was less common for weavers than other traders to have actual space for a shop, where they sold their own produced wares to private customers. That is to say, fabric for clothing and interior furnishings woven in London workshops or home interiors seem mostly to have been sold via mercers, drapers, tailors or wholesale warehouses in the city – if sold locally. Exceptions existed, however, among different categories of weavers, which this essay will look more closely at.

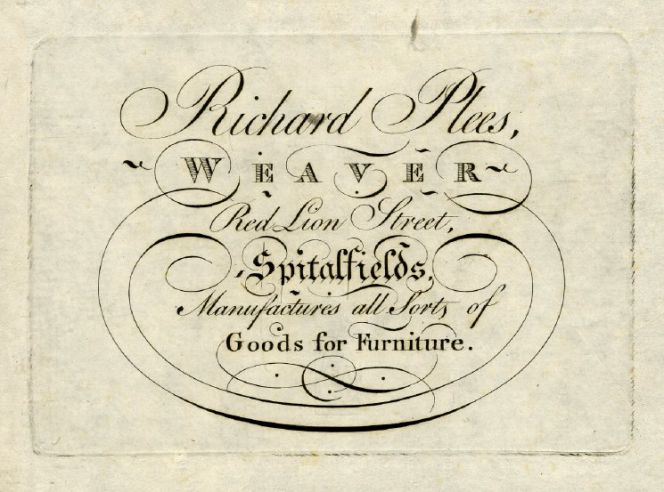

The British Museum Collection online includes a unique selection of trade-cards and bill-heads, about twenty examples are linked to 18th century weavers in London. This undated card reveals that the weaver Richard Plees in Spitalfields manufactured (and probably sold) furnishing goods. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 127.17. Collection online).

The British Museum Collection online includes a unique selection of trade-cards and bill-heads, about twenty examples are linked to 18th century weavers in London. This undated card reveals that the weaver Richard Plees in Spitalfields manufactured (and probably sold) furnishing goods. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 127.17. Collection online).One of the districts considered to have the most skilled weavers was Spitalfields in East End London, where silk weaving had been introduced in the late 17th century by Huguenot immigrants. These skilled French weavers and local people alike who learned the trade via a lengthy apprentice period belonged to various weaver’s Guilds and created the most exclusive cloth. In particular, it was used for every conceivable type of luxury in clothes, accessories and home furnishings. These categories included satins, velvets, brocades, watered silks, paduasoys, watered tabbies, lustrings and mantuas. Despite a multitude of ongoing disputes and restrictions such as petitions, sumptuary legislations, patents, smuggling, dissatisfaction with low wages, competition from Indian calicoes, etc – production prospered during most decades until the 1780s when the silk industry, like linen-weaving, ran into an even greater competition from cotton. The Spitalfields silk manufacturing is regarded to have had a downturn in the late 18th century and first made some revival around 1798.

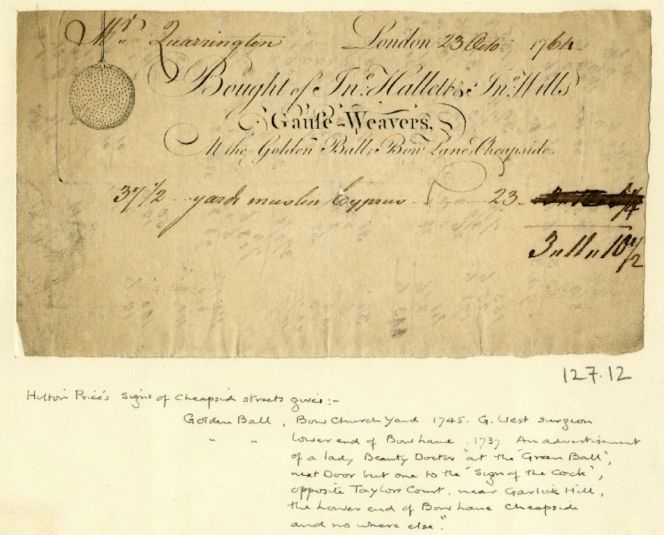

A bill-head dated 23 October 1764, which informed that the Gauze-Weavers at the Golden Ball, Bow Lane at Cheapside in London sold ’37 1/2 yards muslin Cyprus’. Fine transparent muslin – presumably woven by the mentioned weavers – of imported cotton grown at Cyprus. Since a long time Cheapside had been a busy area for manufacturers, Hallett & Mills was one of these textile establishments. Another contemporary trade card (1765), preserved from the same area, reads ‘James Brant, Silk thrower and Silk man, late Richard Finlow’s at the Blue Boar in Cheapside’. A silk thrower had an important role in the pre-weaving process, as such a business winded the silk onto bobbins and was also likely to import raw silk. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal, 127.12. & note about 127.3 Collection online).

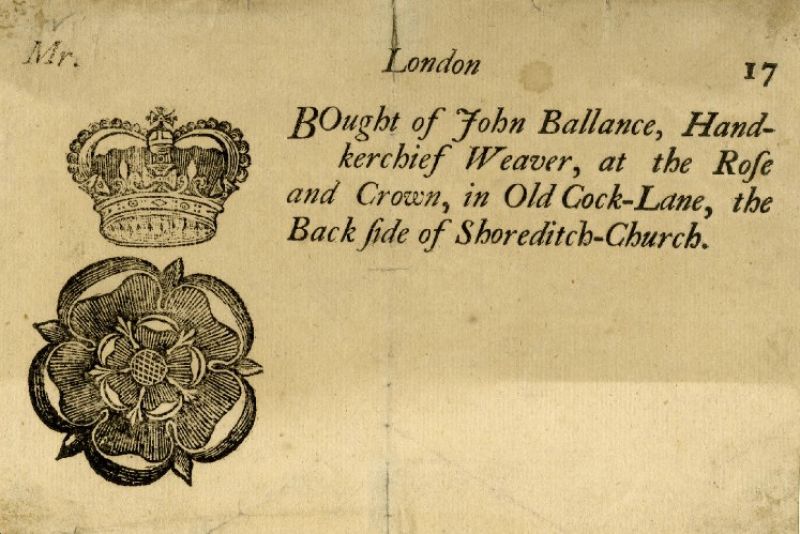

A bill-head dated 23 October 1764, which informed that the Gauze-Weavers at the Golden Ball, Bow Lane at Cheapside in London sold ’37 1/2 yards muslin Cyprus’. Fine transparent muslin – presumably woven by the mentioned weavers – of imported cotton grown at Cyprus. Since a long time Cheapside had been a busy area for manufacturers, Hallett & Mills was one of these textile establishments. Another contemporary trade card (1765), preserved from the same area, reads ‘James Brant, Silk thrower and Silk man, late Richard Finlow’s at the Blue Boar in Cheapside’. A silk thrower had an important role in the pre-weaving process, as such a business winded the silk onto bobbins and was also likely to import raw silk. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal, 127.12. & note about 127.3 Collection online). This undated 18th century bill-head from the handkerchief weaver John Ballance, informed that his premises was situated at Old Cock-Lane in the city of London. However, no information exists if the business wove qualities of cotton, linen or silk. Two further remnants of trade cards linked to handkerchief weavers are also preserved in this collection, both located in Spitalfields, which indicates that silk was the preferred material. The weavers were James Hammond in Wood Street and John Lamy in Gun Street. The latter was researched by the initial collector – Ambrose Heal – who traced this trade card to several individuals of the Lamy family and all were active as handkerchief weavers at this address according to directories of 1755, 1760, 1763, 1768 and 1777. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 127.1 & note about Banks 132.51 & Heal 127.13 Collection online).

This undated 18th century bill-head from the handkerchief weaver John Ballance, informed that his premises was situated at Old Cock-Lane in the city of London. However, no information exists if the business wove qualities of cotton, linen or silk. Two further remnants of trade cards linked to handkerchief weavers are also preserved in this collection, both located in Spitalfields, which indicates that silk was the preferred material. The weavers were James Hammond in Wood Street and John Lamy in Gun Street. The latter was researched by the initial collector – Ambrose Heal – who traced this trade card to several individuals of the Lamy family and all were active as handkerchief weavers at this address according to directories of 1755, 1760, 1763, 1768 and 1777. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 127.1 & note about Banks 132.51 & Heal 127.13 Collection online). Handkerchiefs had multiple functions and were connected to sadness and emotions, practical uses like wrapping up small items and snuff-taking, and invaluable during illness or as a present. It came in varied designs as one colour only, checked, striped or woven in more advanced diaper techniques or with printed patterns. The materials were either silk, linen or cotton – sometimes embellished with embroidery and laces. It may also be noted that the limited amount of fabric needed for a small handkerchief made it reasonably priced for a wider society. Judging by artworks of the period, this useful piece of fabric was usually tucked away in a pocket or concealed in some other way – probably due to traditions or practicality or etiquette.

Just like the handkerchief weavers, a few other individuals within similar trades and shop establishments – who produced small-size woven items – have been traced via these preserved documents. Joshua Crickett, an ‘Engine Narrow and Broad Weaver’ at Bridewell Hospital in London. He described that he made and sold his cotton-wicks, which exceeded the French cottons in brilliancy and quality: ‘The Original and only Inventor of superfine True English Cotton-wicks, both Soft and Stiff for trimming of Lamps and burn without perceptible Smoak…’ (undated 18th century trade card, Heal, 127.9). James Cranch at the Sun & Star no. 10 at Middle Moorfields in London gave his business description as ‘Gause & French Trimming Weaver’. A multitude of small details needed for clothing were part of his assortment, like ribbons, fringes, ruffles and trimmings used for gowns and petticoats. According to preserved directories, James Cranch’s establishment was active at this address from at least 1777 to 1793 (Heal 127.8). Overall, ribbons in various designs of silk, cotton, linen or wool alike formed a noteworthy component for clothing during the 18th century, which was not only used as decoration but also to hide and reinforce seams or to tie together parts of garments, hold up stockings and other practical usage.

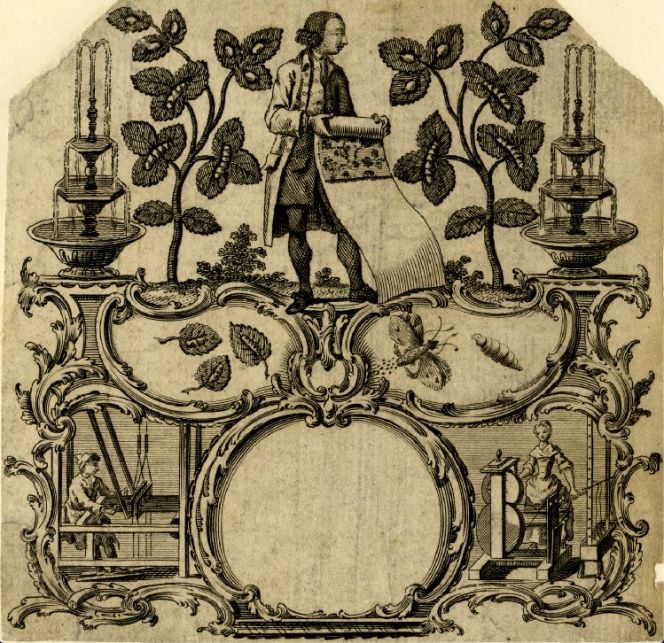

This fragmented anonymous trade card, indicates a mid-18th century weaving establishment, judging by the individuals’ clothing and the beautiful rococo style design. Undoubtedly the firm manufactured various silks or even more likely plain woven silks with printed motifs – due to the silk worms on mulberry leaves, the winding of silk as well as a weaver who worked on a loom with two shafts only, used for or tabby or ribbed fabric qualities. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal, 127.25. Collection online).

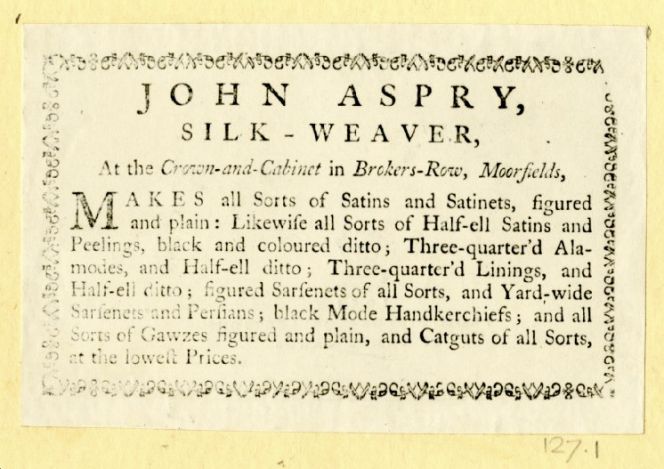

This fragmented anonymous trade card, indicates a mid-18th century weaving establishment, judging by the individuals’ clothing and the beautiful rococo style design. Undoubtedly the firm manufactured various silks or even more likely plain woven silks with printed motifs – due to the silk worms on mulberry leaves, the winding of silk as well as a weaver who worked on a loom with two shafts only, used for or tabby or ribbed fabric qualities. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal, 127.25. Collection online). Silk-Weaver John Aspry in the Moorfields area of London gives a glimpse into what types of plain and figured woven silks, which were woven and put up for sale – ‘at the lowest Prices’ – in his business. Judging by the trade card design, it probably originates from the late 18th century. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards: Banks 127.1. Collection online).

Silk-Weaver John Aspry in the Moorfields area of London gives a glimpse into what types of plain and figured woven silks, which were woven and put up for sale – ‘at the lowest Prices’ – in his business. Judging by the trade card design, it probably originates from the late 18th century. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards: Banks 127.1. Collection online).Two further preserved trade cards are clearly linked to the silk trade. Firstly, the undated mid-century rococo style (Banks, 127.3) Francis Rybot as ‘Weaver and Mercer’, which reveals details of his luxury wares – manufactured as well as sold in ‘end of Smock Alley, Spittle Fields London’. Besides a great variety of English qualities, he sold imported velvets from Holland and Genoa as well as ‘Venetian Poplins’. The second ‘Weaver and Mercer’, named William Wilson had his premises ‘at his Warehouse, Sign of the White Lion’ in the Corner of George St Minories in London (Banks, 84.106). This trade card is marked with the year 1799. The occupation ‘mercer’ indicated he was a businessman who mainly sold fine silks and velvets. A few other randomly preserved trade cards linked to weavers include the weaver Isaac Bradshaw, who ‘Makes Ribbons, Ferrits, &c. and sells Wholesale upon the very lowest Terms’ (Heal, 127.2). Together with a ‘Weaver and Haberdasher’ named William Poole, who in 1778 had his premises at no 53 Cheapside in London (Heal 127.18-19) and the ‘Weaver and Warehouse-man’ Joshua Warne in Newgate Street (Banks, 127.4).

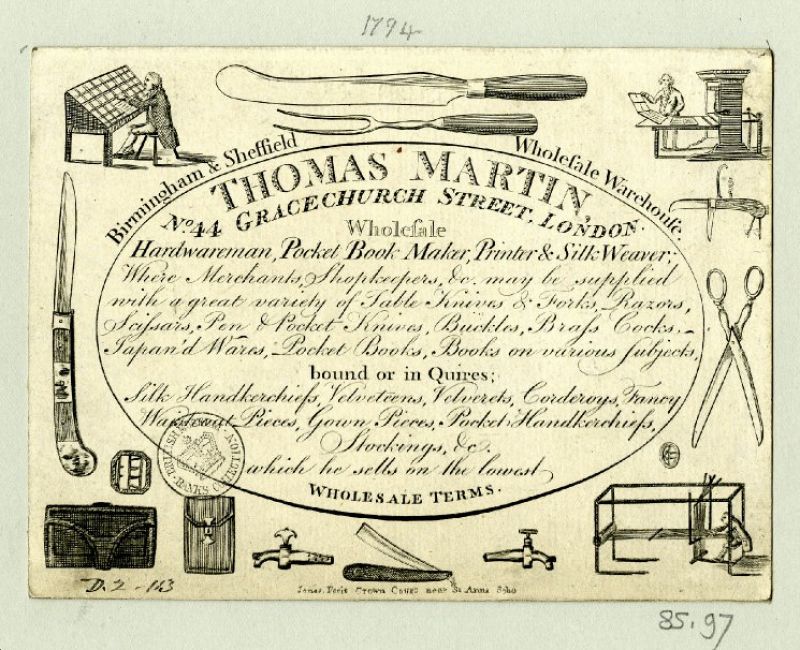

At the end of the century with the growing consumer revolution, larger establishments also became more common. Like this ‘Wholesale Warehouse’ which sold a variety of goods to the lowest prices. Intertwined among several occupations as hardware man, pocket book maker and printer, Thomas Martin was also engaged in silk weaving. Here illustrated and described in detail – among other silks he sold handkerchiefs, gown pieces, stockings and velvets – on this trade card which has been marked with the year 1794 in pencil. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 85.97. Collection online).

At the end of the century with the growing consumer revolution, larger establishments also became more common. Like this ‘Wholesale Warehouse’ which sold a variety of goods to the lowest prices. Intertwined among several occupations as hardware man, pocket book maker and printer, Thomas Martin was also engaged in silk weaving. Here illustrated and described in detail – among other silks he sold handkerchiefs, gown pieces, stockings and velvets – on this trade card which has been marked with the year 1794 in pencil. (Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Banks 85.97. Collection online). To conclude with some further thoughts on the London silk weavers. Many workers lived under poor or very modest circumstances and silk qualities were often woven on commission from their own home for a master weaver. A multitude of in-depth research has been made over the last hundred years about living conditions for skilled and unskilled labourers of silk manufacturing in Spitalfields and other nearby areas – where poverty and wealth lived side by side. In particular, by the late textile historian Natalie Rothstein during the 1950s to 1990s. Minute details are therefore known about individual master weavers, their workshops and order books, male and female silk designers, sample books, specialisation in various qualities from advanced flowered damask to plain-woven silks, number of employed journeymen, female silk weavers and winders, as well as young apprentices coming and going over the years.

However, hand-written documents or prints which registered that these 18th century master weavers simultaneously acted as shop owners and manufacturers of fabric have seldom survived. The combination existed, evident via some of the illustrated and referenced trade cards, but it seems to have been quite unusual. One disadvantage of such an arrangement was the weavers’ long working hours in a specialist workshop or in their own home – assisted by apprentices, journeymen, draw boys, family members, etc. – which, either way, gave limited time to keep a time-consuming selling establishment. Especially for the hundreds of silk weavers who had their homes and workplaces in Spitalfields or nearby Bethnal Green, White Chapel, etc – which restricted the chances for most to put their goods up for sale in such a crowded area of similarly skilled professionals. Undoubtedly, the majority of these master weavers must have had a variety of options to sell their silks. Either assisted by local silk masters or via mercers, drapers, haberdashers and wholesale warehouses in the City of London and nearby districts of the capital or in the form of preorders from well-to-do customers in Great Britain, the British colonies or via merchants for export to other countries.

Sources:

- Anishanslin, Zara, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World, Yale 2016.

- British History Online, ‘Industries: Silk-weaving’, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2…, ed. William Page, pp. 132-137, London 1911.

- British Museum, Collection Online, The Department of Prints and Drawings. Originally collected by Sarah Sophia Banks (1744-1818) & Ambrose Heal (1872-1959). (Search words: ‘trade cards weaver’ & ‘trade cards spinning).

- Ellis Miller, Lesley, Selling Silks: A Merchant’s Sample Book 1764, V&A, London 2014.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914, London & Whitby 2015 (From the section: ‘Textile Occupations and Trades from a Wider Perspective’, pp. 54-69).

- Rothstein, Natalie, Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century: in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 1990.

- Siegelaub, Seth, ed. Bibliographica Textilia Historiae, New York 1997 (p. 282 Rothstein, Natalie).

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Notice: This is the fifth and final essay about textile occupations, based on information via 18th century trade cards and bill-heads kept at the British Museum. The earlier iTextilis Essays:

29 May 2014: ‘Early Fashion & Cloth Trade Cards – a Selection from 1720s to 1850s’.

18 November 2015: ‘Haberdashers – 18th & 19th Century Trade-cards’.

17 April 2016: ‘A Study of Upholstery – in 18th & 19th Century London’.

11 July 2016: ‘18th Century Silk Dyers – in London’.

A couple of other Textilis Essays over the years have also been assisted by single trade cards from this extensive collection online.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE