ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

A JOURNEY TO COLMAR IN 1785

– Education of Swedish Aristocracy and Practical Travel Arrangements

The Christinehof manor house situated in southernmost Sweden, holds an extensive historical archive with documents connected to the aristocratic Piper family stretching over 300 years, with the earliest traces from the late 17th century. This essay will look closer into the education of three boys – aged 12, 14 and 15 at the time of their travel to École militaire de Colmar in 1785 – via the initial journey from their home country towards the harbour town of Ystad. In this place, they boarded a ship to Stralsund, continued with horse and carriage through the German-speaking states, among other places, making stops at Rostock, Hamburg, Cassel, Darmstadt, Mannheim, Landau and into France via Strasbourg to finally reach Colmar on 13th September after a 26-days-long journey. A second continuous essay aims to focus on the three young individuals’ education at the school lasting up to the year 1788.

This somewhat later depiction gives a good view of Krageholm manor house, one of the Piper family’s country retreats since 1704, which came to be the starting point of the journey on 18th August in 1785. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Sweden. Hand-coloured engraving, by U. Thersner 1817. Digital source – Alvin record. No. 183360).

This somewhat later depiction gives a good view of Krageholm manor house, one of the Piper family’s country retreats since 1704, which came to be the starting point of the journey on 18th August in 1785. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Sweden. Hand-coloured engraving, by U. Thersner 1817. Digital source – Alvin record. No. 183360).The three Piper brothers – Carl Claes (1770-1850), Gustaf (1771-1857) and Eric (1772-1833) – were sons of Carl Gustaf Piper (1737-1803) and Hedvig Catharina Ekeblad (1746-1812). Their main home seems to have been in Stockholm, but according to preserved correspondence, the family also occasionally or for more extended periods lived on their other estates, one of these was the Krageholm manor house in southernmost Sweden. Daily life during the journey towards Colmar can be followed in an unusual exactness, due to the accompanying Andreas Norberg, who sent exhaustive letters to the boys’ father and additionally kept an account over travel expenses. Besides Norberg as responsible for the safety, clothes, food and the overall installation at the school for the three Piper brothers, two other youngsters from a wealthy Stockholm family (Carl and Fredrik Evert Taube) and two servants travelled along on the journey.

The carriage initially took them the relatively short distance from Krageholm to Ystad, where they boarded a ship. A letter from Norberg, dated (22nd August, 1785) a day after they safely arrived in Stralsund vividly explained details of the crossing which off and on had been troublesome ‘as the wind mostly was contrary’. It is also evident that their carriage must have been substantial in size – due to that it took eight persons and luggage – was transported onboard as Carl Claes and Eric were seasick and found it easier to sleep in the carriage on deck compared to the cramped cabin. Meanwhile, the middle son Gustaf ‘did not feel the slightest inconvenience at sea and was just as cheerful as ever ashore’. Furthermore, it appears like food had been prepared at home as Norberg continued: ‘The provisions came in handy and we all had a splendid appetite’.

Grand Tours were popular for young men of the aristocracy, but prior to this age, it was usual as well to fulfil part of one’s childhood education in an international environment. If aiming for military or formal state positions later in life, École militaire de Colmar may have been seen as a natural choice during the 1780s for wealthy European protestants, due to that the École Militaire in Paris only accepted catholic students. This oil on canvas portrait of a well-dressed young man in up-to-date fashion, with visible lace frill down the front and at the wrists on his shirt, red silk neckerchief, matching waistcoat and coat – most probably depicted one of the Piper brothers. That is to say Carl Claes, Gustaf or Eric prior to their several year-long education on the Continent. (Collection: Christinehof manor house, Sweden). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

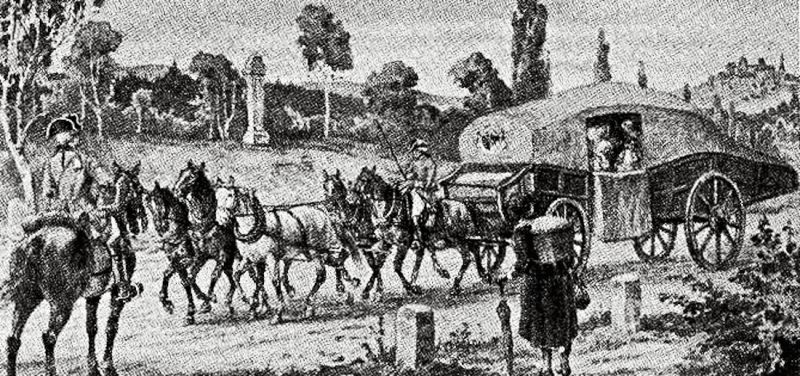

Grand Tours were popular for young men of the aristocracy, but prior to this age, it was usual as well to fulfil part of one’s childhood education in an international environment. If aiming for military or formal state positions later in life, École militaire de Colmar may have been seen as a natural choice during the 1780s for wealthy European protestants, due to that the École Militaire in Paris only accepted catholic students. This oil on canvas portrait of a well-dressed young man in up-to-date fashion, with visible lace frill down the front and at the wrists on his shirt, red silk neckerchief, matching waistcoat and coat – most probably depicted one of the Piper brothers. That is to say Carl Claes, Gustaf or Eric prior to their several year-long education on the Continent. (Collection: Christinehof manor house, Sweden). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.In a letter dated 23rd August in Stralsund, it was noted that the group stayed at an inn to rest. They visited some friends of the family who praised the school in Colmar, in particular in regards to that students learned attentiveness and courteousness among the ordinary subjects. By now, the carriage had to be repaired prior to the continuous journey towards Hamburg. Five days later, on arrival at this place, a new letter was sent explaining some problems along the route caused by the intense raining leaving the roads almost impassable. Norberg highlighted some unforeseen as well as expected expenses: ‘A new wheel in Damgarten with tip money for a man who guarded the carriage, 3 Rixdollar and 12 Shillings’, whilst before entering Rostock they had to pay the ‘Mecklenburg toll’. Along this stretch of the journey, the correspondent additionally mentioned that the company so far had managed with ‘5 horses and one post chaise’, but he feared that they further on needed six horses. This matter became an extra cost, but could ease the journey and make it faster. The somewhat earlier dated image below gives an idea of how their equipage may have been constituted.

Depiction of a mid-18th century post chaise or spacious carriage with room for a group of travellers, drawn by five horses in the German area/Saxony. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).

Depiction of a mid-18th century post chaise or spacious carriage with room for a group of travellers, drawn by five horses in the German area/Saxony. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).In the same letter which explained their daily life in Hamburg, Norberg noted some lines about the young boys’ good behaviour and diligence too: ‘as they made their small observations which they faithfully wrote down on paper and inserted in their journals’. After two days of staying in the city, having time to catch up on correspondence and make some purchases of necessary items, the trip went southward on 30th August towards Hannover. Once again, the carriage was causing delays as noted in a letter by Norberg on 4th September: ‘The carriage has demanded repeated repairs, which we in some way had anticipated, but so far we have not come in such difficulties that we must stop in the middle of the main road’. Their journey continued further over two days via Eimbeck, Northeim, Göttingen towards Cassel: from where the same letter explained that ‘the inns are so occupied, that the inn owners they have to sleep outdoors’. At the arrival at Cassel, the correspondent mentioned, he had chosen ‘an innocent pastime’ for the boys in a form of a German theatre play for the cost of 4 Rixdollars and 6 Shillings.

The following letter was sent from Frankfurt on 7th September and gave information about the previous three days of travel. Once again, one of the wheels had to be repaired, but positive news was not lacking. The young boys’ tempers had been excellent, the weather being warm and pleasant, whilst the main roads were bordered with alleys of fruit trees tempting to ‘an extravagant fruit-eating’. In Frankfurt, they visited ‘the Hospital and Dome’ and stayed at an inn which was regarded rather good and suitable with comfortable beds. Three days later, an even more optimistic letter was sent from Mannheim, which gave a description of the tour via these two cities. Including: ‘We travel through something like a continuous garden. The passages have been the most beautiful imaginable and the sky had with its lavish splendour blessed this country.’ When reaching Mannheim – and staying for two nights – they visited ‘the Library, Statues and the Academic garden’. Furthermore, various dirty clothes were left to be laundered and the wheel had to be repaired again. Emotions and homesickness were also present in this letter as Norberg wrote: ‘The young counts’ hearts sink when they think of being so far away from their dear parents, yes, they even have worries about that they shortly must leave me too’.

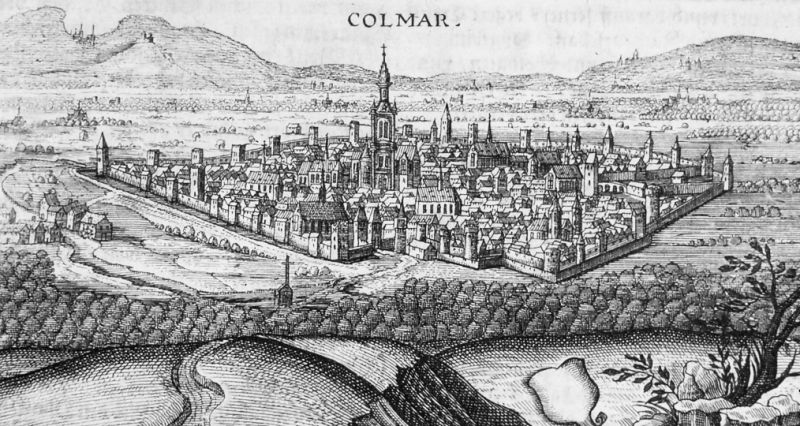

On 10 September the company left Mannheim in the post chaise and travelled via Neustadt, Landau, Candell and towards Strasbourg to reach Colmar three days later. | Engraving of ‘Colmar vue générale vers 1750’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).

On 10 September the company left Mannheim in the post chaise and travelled via Neustadt, Landau, Candell and towards Strasbourg to reach Colmar three days later. | Engraving of ‘Colmar vue générale vers 1750’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain). Everybody seemed to have been immensely pleased at the arrival to Colmar, according to a letter written by Norberg on this day. The most pleasing was that ‘the young Counts during the journey had kept a good health, making all medicines kept among their luggage unnecessary’. Norberg came to stay another fourteen days to install the future students, to make sure that all eventualities worked smoothly after plan, arrange for school uniforms and so that the École militaire lived up to its good reputation.

Original documents were written in Swedish and French. All quotes in this essay have been translated to English. To be continued with an essay about the school years in Colmar, stretching from 1785 to 1788 – based on a selection of unique primary sources linked to the young counts’ timetables, reports, marks, receipts, lists of clothes, and other preserved 1780s documents.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (Oil on canvas: portrait of a young nobleman, 1780s).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Pojkarna Pipers utlandsstudier’, Österlen, pp. 5-14. 1999 [pp. 5-9].

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive, no. E/III: including, 1. Letters 1784-88. 2. Account book in 1785. 3. Miscellaneous documents. & G/V 2: Receipts etc. linked to the Colmar journey).

In concluding words about the historical archive of Högestad and Christinehof, at the Christinehof manor house in southernmost Sweden. When and under which circumstances the archive got its abode here is impossible to trace with certainty, but the older parts of the collection probably have a long history in this country house. It may be assumed that the employed at the manor house office kept the historical records in good order already during the 18th and 19th centuries, but it was not until the years 1973 and 1974 that the archive received a complete catalogue. An update of this catalogue system and a complete review of the archive was made by the IK Foundation (Stiftelsen IK) from 1990 to 1994, who also published the Complete Catalogue of the archive in the Swedish language (with an English summary) in 2016. All documents are kept in acid-free boxes on an airy wooden shelf system, while maps have protective wrappings of acid-free kraft paper. The preservation follows the recommendations drawn up by the French research Centre for document Conservation and Bibliothèque nationale de France. | Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

In concluding words about the historical archive of Högestad and Christinehof, at the Christinehof manor house in southernmost Sweden. When and under which circumstances the archive got its abode here is impossible to trace with certainty, but the older parts of the collection probably have a long history in this country house. It may be assumed that the employed at the manor house office kept the historical records in good order already during the 18th and 19th centuries, but it was not until the years 1973 and 1974 that the archive received a complete catalogue. An update of this catalogue system and a complete review of the archive was made by the IK Foundation (Stiftelsen IK) from 1990 to 1994, who also published the Complete Catalogue of the archive in the Swedish language (with an English summary) in 2016. All documents are kept in acid-free boxes on an airy wooden shelf system, while maps have protective wrappings of acid-free kraft paper. The preservation follows the recommendations drawn up by the French research Centre for document Conservation and Bibliothèque nationale de France. | Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE