ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

A STUDY OF UPHOLSTERY

– in 18th & 19th Century London

The rich information on trade cards and bill-heads in the form of illustrations, printed texts as well as hand-written notes may be compared with observations by the social reformer Charles Booth for historical studies of London. Together these sources give a multitude of facts linked to upholstering as an occupation and other interests of the trade during two hundred years. This case study aims to present a glimpse of the commerce of such goods, in the eyes of the shopkeepers and customers, as noticed on trade cards from the 18th- and first half of the 19th centuries. This is to be contrasted with the later observations – mainly the 1880s-1900s – by Booth, where the conditions and daily lives of the manufacturers/shopkeepers, as well as the upholstery workers, were included.

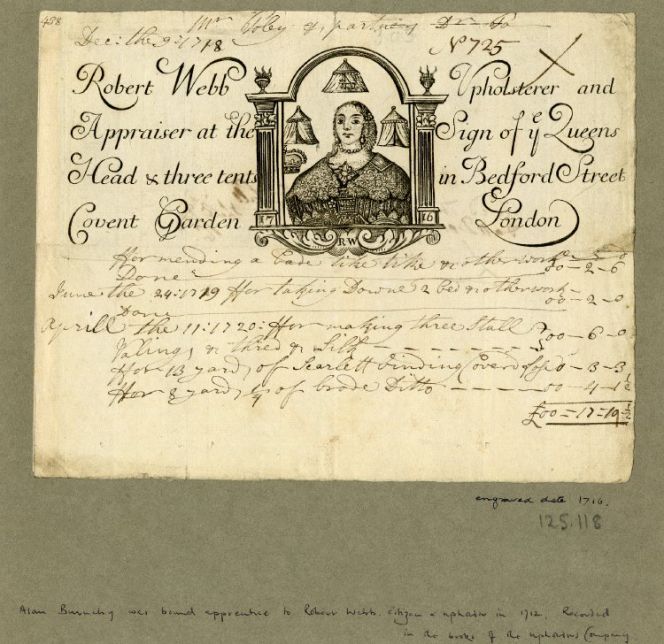

The study is based on a search for “trade cards upholsterer”, which gave 103 results. This illustrated card originates from Robert Webb in Bedford Street, Covent Garden and is the earliest example from the collection, dated 1718. Only one receipt is older, written in 1689 and totalling the large sum of £57.07.5 from the upholsterer John Wells at the Kings Head Fleet Street in London. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.118. (Collection online).

The study is based on a search for “trade cards upholsterer”, which gave 103 results. This illustrated card originates from Robert Webb in Bedford Street, Covent Garden and is the earliest example from the collection, dated 1718. Only one receipt is older, written in 1689 and totalling the large sum of £57.07.5 from the upholsterer John Wells at the Kings Head Fleet Street in London. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.118. (Collection online).Sir Ambrose Heal (1872-1959) had a historical interest foremost in 18th century trade cards. Thousands of cards in his former care are kept at the British Museum; among these are 103 cards linked to upholsterers. This selection of cards also includes Heal’s factual notes, giving the time range for most businesses and, therefore, an approximate year for the majority of these trade cards, bill-heads and receipts. His sources for dating the individual establishments were primarily poll books and directories of London. The hand-written receipts are additionally dated concerning the order, purchase or delivery of the goods.

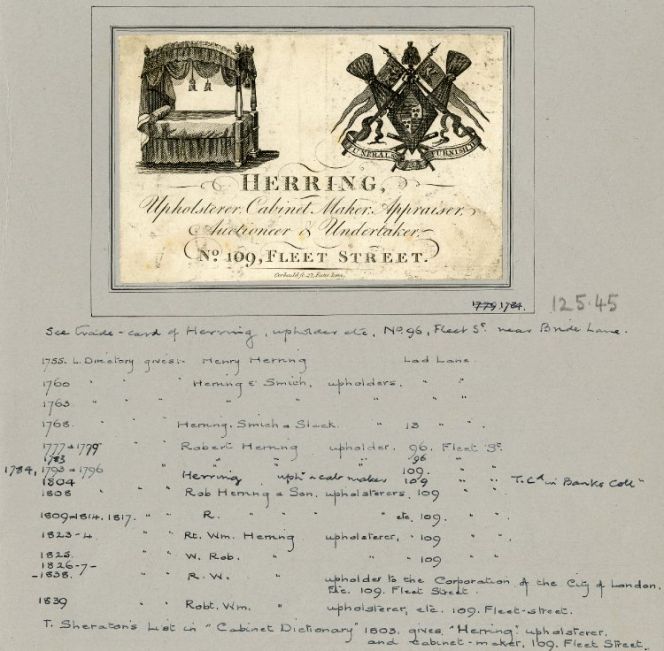

An example of Heal’s meticulous notes of a long-lived trader on Fleet Street, who continued in business from 1755 to 1839. The trade card itself is dated to 1784. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.45. (Collection online).

An example of Heal’s meticulous notes of a long-lived trader on Fleet Street, who continued in business from 1755 to 1839. The trade card itself is dated to 1784. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.45. (Collection online).Even if upholstery of furniture was the link between all these traders a multitude of goods and services were included in such businesses. The branches for textiles could, for example, be bedding, carpets, curtains, feather beds, mattresses and Venetian blinds. However, the upholstery trade was also often combined with cabinet making, chair manufacturers, selling of looking glasses, paper for rooms, and all sorts of household goods, such as pianos or secondhand furniture/goods. Additional trades could be appraiser, auctioneer, undertaker, estates were bought and sold as well as that “warehouses” were often mentioned in various combinations to emphasise the extensive trade. Lastly, some rarer business opportunities were listed as “dealer in”: coals, upholstery to the admiralty, cabin furniture for ships and military tents.

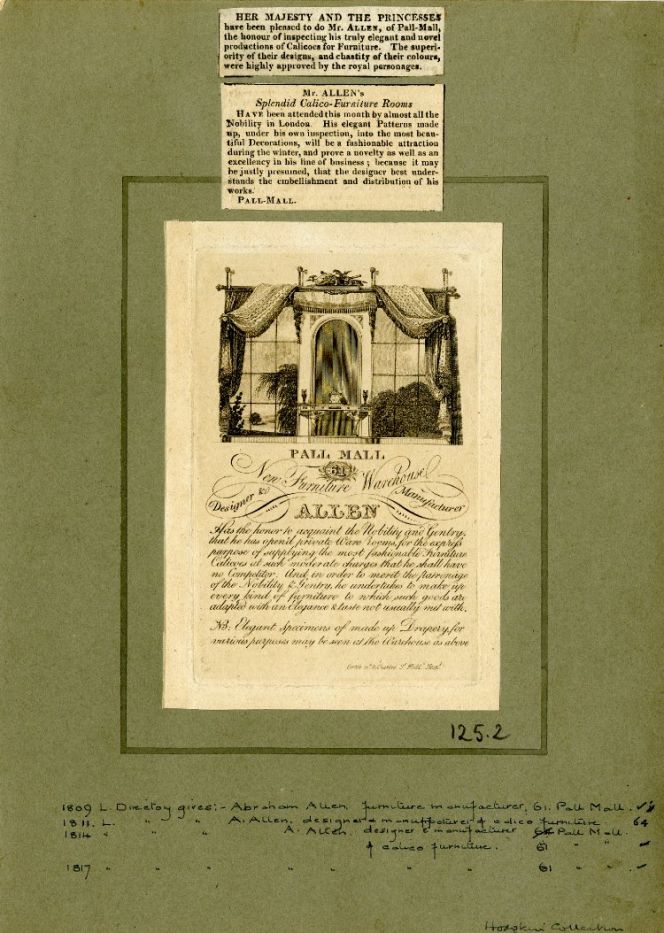

A group of trade cards originate from “The New Furniture Warehouse Allen” who aimed for a wealthy London clientele. According to information collected by Heal, this establishment was situated at 61 Pall Mall from at least 1809 to 1817. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.2. (Collection online).

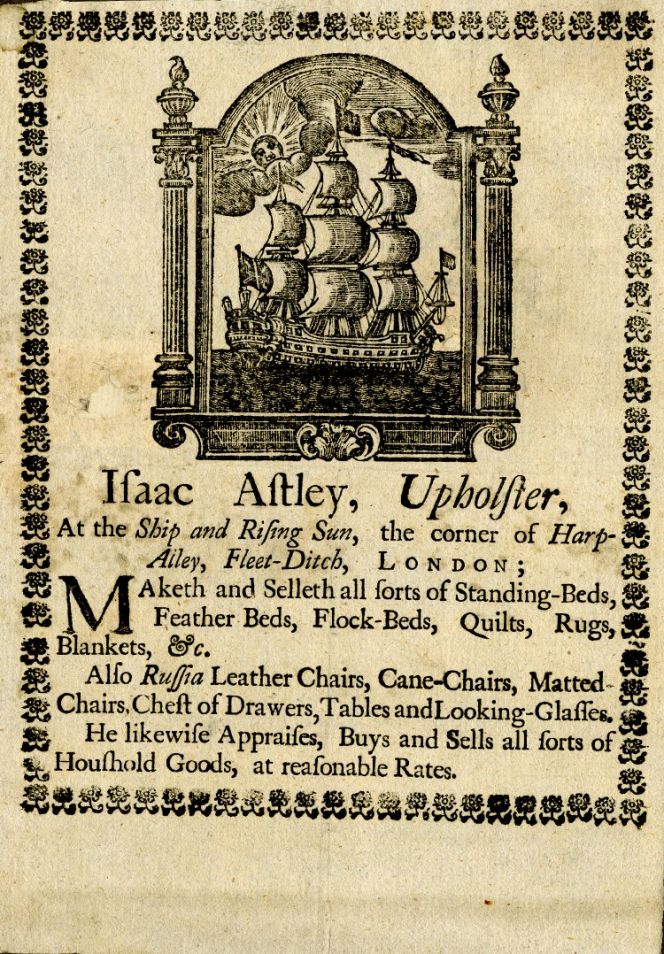

A group of trade cards originate from “The New Furniture Warehouse Allen” who aimed for a wealthy London clientele. According to information collected by Heal, this establishment was situated at 61 Pall Mall from at least 1809 to 1817. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.2. (Collection online). Far from all trade cards aimed to a wealthy or well-to-do clientele, this 18th century example from ‘Isaac Astley, Upholster’ in Fleet-Ditch, London lists his wares for sale, ending with ‘Buys and Sells all sorts of Household Goods, at reasonable Rates’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.6. (Collection online).

Far from all trade cards aimed to a wealthy or well-to-do clientele, this 18th century example from ‘Isaac Astley, Upholster’ in Fleet-Ditch, London lists his wares for sale, ending with ‘Buys and Sells all sorts of Household Goods, at reasonable Rates’. Courtesy of: © Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 125.6. (Collection online).This study will not draw conclusions about pricing, inflation or the financial side of the upholstery trade, but it may be mentioned that quite substantial sums were the norm – £10-£40 was not unusual – upholstering, curtains and ordering of furniture were in general costly investments. One receipt even stretches over three pages and totals £155.22.5 by the upholsterer Johan Hanbury, who listed upholstery work and furniture delivered/ordered in various months by one wealthy customer in the period from 1751 to 1758.

The trade cards and the receipts from this collection, dating from 1689 to 1841, only demonstrated the upholstery trade from the view of the owner/manufacturer and their customers. The many workers who were part of this trade are invisible. Therefore, this case study is backed up with some notes by the extensive material from Charles Booth (1840-1916) and an introduction to his work from the 1880s to the early years of the 20th century.

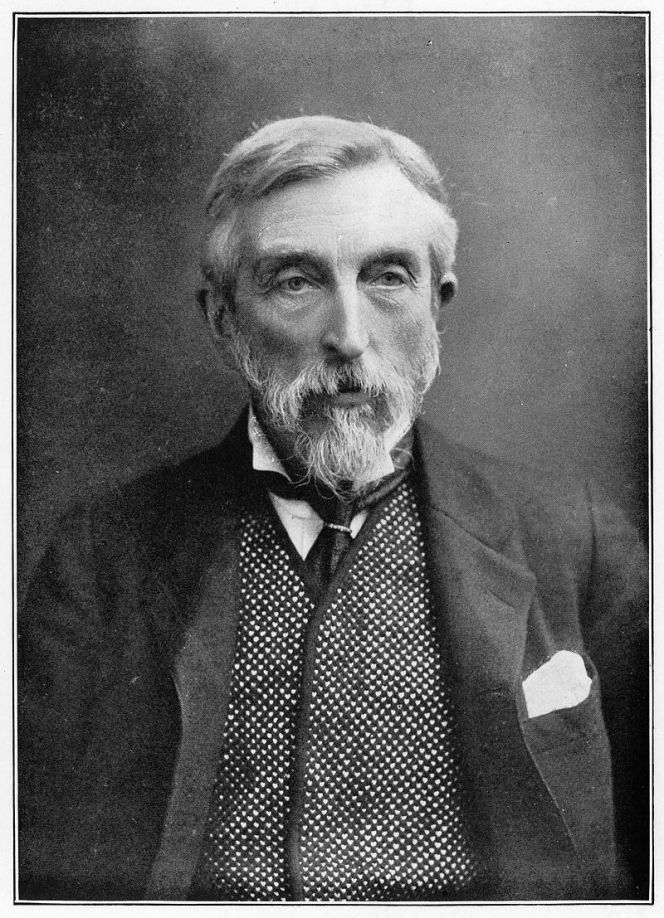

Charles Booth was a social reformer and one of a stream of middle-class people with a philanthropical approach to various social matters, and as with many others it was an urban environment that he chose for his work. His work found an outlet in his survey “Life and labour of the People in London”, in which he drew particular attention to such questions as unequal incomes, housing, working conditions, wages, education, religion and politics. A considerable number of textile workers suffered from a variety of problems to do with their living and working conditions – upholsterers was one of them. Booth was by no means the first to do this kind of social research, which followed other private initiatives, official enquiries, and of course census statistics. Undated photo (ca 1890s) by Russell and Sons. Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, Iconographic Collections, M0013547.

Charles Booth was a social reformer and one of a stream of middle-class people with a philanthropical approach to various social matters, and as with many others it was an urban environment that he chose for his work. His work found an outlet in his survey “Life and labour of the People in London”, in which he drew particular attention to such questions as unequal incomes, housing, working conditions, wages, education, religion and politics. A considerable number of textile workers suffered from a variety of problems to do with their living and working conditions – upholsterers was one of them. Booth was by no means the first to do this kind of social research, which followed other private initiatives, official enquiries, and of course census statistics. Undated photo (ca 1890s) by Russell and Sons. Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, Iconographic Collections, M0013547.In Booth’s material, the upholstery workers were mentioned – particularly regarding their wages – side by side with matters concerning the shop owners of such businesses. One may also speculate that due to the fact that upholstery was a skilled trade including several years of training, these manufacturers and possibly also the majority of their workers could avoid the most deprived areas of London, which is not a reality for various other textile workers like untrained tailors or numerous women working as seamstresses or laundresses. This circumstance is also demonstrated on the “Booth Poverty Map,” which mainly places people involved in the upholstery trade in the light blue, purple, and pink areas, which are regarded as poor, mixed, and relatively comfortable streets. Some individuals, even in a red area – were considered middle class/well-to-do. As was the case in a ‘Completed wages questionnaire: Thomas Lawes and Company, cabinet makers and upholsterers, 65 City Road, 7 March 1893.’ It may also be noted that an extensive census search of individuals working within the upholstery trade, would give further detailed evidence for where and under which family circumstances this occupational group lived in late 19th century London.

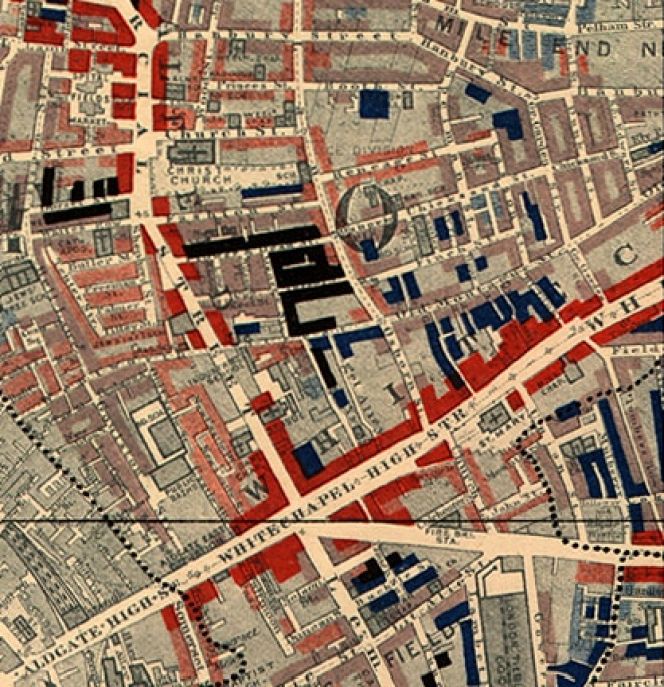

Part of Booth’s map of Whitechapel in 1889. This small detail of the London map illustrates how the “well-to-do” areas in red were situated very close to the poorest area of them all – the black regarded as “semi-criminal”. Generally it can be stated that many main roads, like Whitechapel High Street on this map, had dominantly middle-class to well-to-do inhabitants, whilst the smaller streets and alleys were a mix of various social classes depending on the area (Public Domain).

Part of Booth’s map of Whitechapel in 1889. This small detail of the London map illustrates how the “well-to-do” areas in red were situated very close to the poorest area of them all – the black regarded as “semi-criminal”. Generally it can be stated that many main roads, like Whitechapel High Street on this map, had dominantly middle-class to well-to-do inhabitants, whilst the smaller streets and alleys were a mix of various social classes depending on the area (Public Domain).Booth’s interests included all trades, but when it concerned upholsterers, he mainly made notations for lists of practitioners of this occupation, interviews, the fact that they were often also cabinet makers, wages for these workers and facts relevant to the Society of Upholsterers. This occupation was mentioned on 29 individual occasions in his original survey notebooks, as the third most listed textile trade after tailors and drapers.

Sources:

- British Museum, Collection online (search words: ‘trade card upholsterer’).

- Charles Booth Online Archive, original survey notebooks from London 1886-1903 & the Poverty Map of 1889.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 67-69).

- O’Day, Rosemary & Englander, David, Charles Booth and social investigation in nineteenth-century Britain, Open University course A427. Milton Keynes 1995.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE