ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

A SWEDISH TRADE DICTIONARY

– Global Textile Goods in 1768

18th century housekeeping books described everything used within the household in the minutest detail, often referencing earlier printed publications. The primary aim was to encourage an economy based on domestic production within a family or village, which reflected the mercantile spirit of the times, stressing and informing, above all, the benefits for the domestic economy of the society as a whole. These books included observations on natural dyes, raw materials, a wide selection of fabrics, laundry, sail cloths, spinning, weaving, feathers for bolsters, etc. However, these domestic matters and produce were, in reality, not covering the demands and desire for many products or raw materials produced outside the local sphere. The reader could instead find information about textiles in some contemporary dictionaries, which listed imported goods for everyday needs as well as items of luxury. This essay will focus on one such dictionary, published by Carl Magnus Könsberg in 1768. Five books only are kept in Swedish reference libraries today of this rare and informative 120-page dictionary.

A view of Uppsala, seen from the south, in 1770. This detailed engraving is almost contemporary with Carl Magnus Könsberg’s (1740-c.1772/75) study period in Uppsala in the early 1760s. Among other teachers, he listened to Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) lectures, probably briefly, since no results or written works from Könsberg are known to have existed. Even so, the young student must have been one of the many hundred disciples who spent time in the Royal Academy Botanical Garden and other linked locations to the university in Uppsala – partly visible in this picture. Despite that, he died young, in his early to mid-30s – after his student years, he published this detailed dictionary in 1768, and in between, he had diverse occupations. Including work as a journalist in local papers, a teacher, keeping a bookstall, a proofreader on a printing work and finally, a soldier in 1771. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:103570. Public Domain. Engraver; Fredrik Akrel, 1748-1804).

A view of Uppsala, seen from the south, in 1770. This detailed engraving is almost contemporary with Carl Magnus Könsberg’s (1740-c.1772/75) study period in Uppsala in the early 1760s. Among other teachers, he listened to Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) lectures, probably briefly, since no results or written works from Könsberg are known to have existed. Even so, the young student must have been one of the many hundred disciples who spent time in the Royal Academy Botanical Garden and other linked locations to the university in Uppsala – partly visible in this picture. Despite that, he died young, in his early to mid-30s – after his student years, he published this detailed dictionary in 1768, and in between, he had diverse occupations. Including work as a journalist in local papers, a teacher, keeping a bookstall, a proofreader on a printing work and finally, a soldier in 1771. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:103570. Public Domain. Engraver; Fredrik Akrel, 1748-1804).The content of Carl Magnus Könsberg’s dictionary – including textile commerce – may be exemplified with silks, printed calicoes or handkerchiefs imported via the East India Trade or pieces of cotton, angora goat hair and fine yarns originating in the wide-stretching area of the caravan routes, later named the Silk Road, as well as textile dyes from the Mediterranean or fine broadcloth via the British trade.

The listings below demonstrate a rich variation of textiles and dyestuffs included in the book (Short Description of Domestic and Foreign Trading Goods…). A selection of words is presented in alphabetical order from the Swedish language, with a complete English translation placed within brackets – which aims to give further insight into his thoughts and facts about the textile trade in the 1760s.

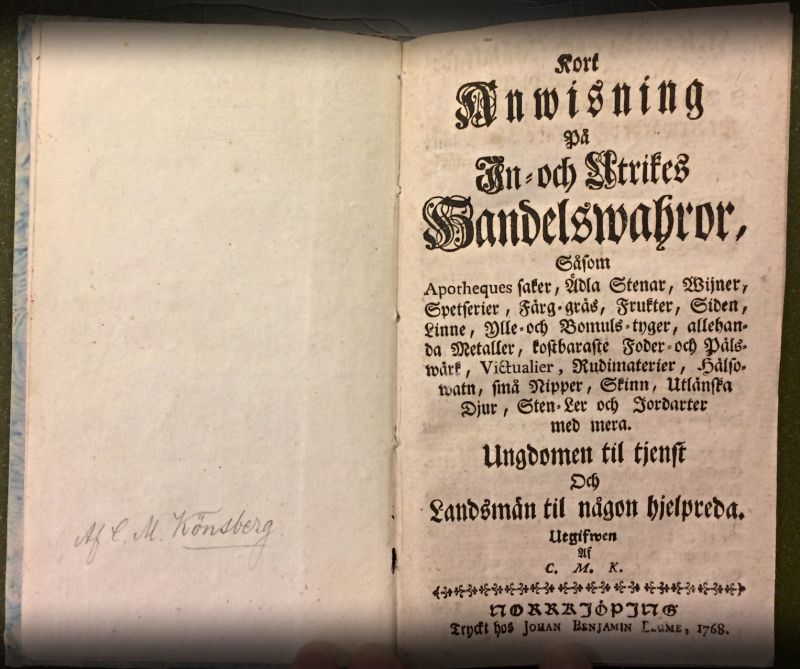

The restrictive regulations related to ‘superfluity and foreign luxury goods’ could, in specific contexts, make it difficult for people in Sweden to use well-liked products. Periodically and in various parts of the country, those rules were strengthened from the 1720s. They remained in force into the next century, which had considerable consequences for the farmers and their families regarding the material and colours of their clothes and interior furnishing textiles. Bans like those could, for instance, restrict the availability of such popular dyestuffs as indigo, common madder and cochineal. Trade in textile goods, domestically as well as abroad, was, in any case, considerable, which can be studied in Carl Magnus Könsberg’s book on trading goods, dated 1768. That publication is arranged like an encyclopaedia from A to Z and provides an insight into the profusion of desirable trading goods in circulation in Sweden. (From: Könsberg, Carl Magnus, ‘Kort anwisning på in- och utrikes handelswahror…’, 1768).

The restrictive regulations related to ‘superfluity and foreign luxury goods’ could, in specific contexts, make it difficult for people in Sweden to use well-liked products. Periodically and in various parts of the country, those rules were strengthened from the 1720s. They remained in force into the next century, which had considerable consequences for the farmers and their families regarding the material and colours of their clothes and interior furnishing textiles. Bans like those could, for instance, restrict the availability of such popular dyestuffs as indigo, common madder and cochineal. Trade in textile goods, domestically as well as abroad, was, in any case, considerable, which can be studied in Carl Magnus Könsberg’s book on trading goods, dated 1768. That publication is arranged like an encyclopaedia from A to Z and provides an insight into the profusion of desirable trading goods in circulation in Sweden. (From: Könsberg, Carl Magnus, ‘Kort anwisning på in- och utrikes handelswahror…’, 1768).- Atlas (Atlas). ‘A rather well-known fabric, which originally was woven in East India, but now it is made in France and Italy, particularly in Genua, Meyland, Lucca and Bologna.’

- Band (Ribbon/s). ‘This is produced in many countries in the world. A multitude of silk ribbons is woven in Basel. In Halle in Saxony, ribbons of gold and silver are made after French patterns. In England and Italy, likewise. Silk ribbons are produced in Paris, Lyon and Tours. One can get twined linen ribbons from Holland and Flanders. Woollen ribbons are manufactured in Amiens and some places in Picardie.’

A pedlar and his female customer are depicted on an oil canvas circa 1780s-90s by Pehr Hilleström. The painting gives a detailed view of what sort of goods were for sale, which were special privileges for rural trading, commerce carried out in a south-north direction from Skåne to southern Norrland in Sweden. Interestingly, Könsberg noted that, concerning ribbons, ‘In Sweden, a considerable amount of ribbons are made, so it seems unnecessary to import these from abroad.’ (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NM 1424).

A pedlar and his female customer are depicted on an oil canvas circa 1780s-90s by Pehr Hilleström. The painting gives a detailed view of what sort of goods were for sale, which were special privileges for rural trading, commerce carried out in a south-north direction from Skåne to southern Norrland in Sweden. Interestingly, Könsberg noted that, concerning ribbons, ‘In Sweden, a considerable amount of ribbons are made, so it seems unnecessary to import these from abroad.’ (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NM 1424).- Bomull (Cotton). ‘Shipped from Constantinople, Alexandria and Rosetta in Egypt. It grows abundantly in Africa and America, yes even in Spain and on some other islands and archipelagoes in the Mediterranean, but mostly in Asia.’

This cotton fabric with woven red lines and painted design from the Coromandel coast, traded to Sweden via the Swedish East India Company circa 1740s-1760s, is comparable in time, geographical location and quality to Könsberg’s note about Indian cotton fabrics below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Anders Berch Collection. NM.0017648B:71A. DigitaltMuseum).

This cotton fabric with woven red lines and painted design from the Coromandel coast, traded to Sweden via the Swedish East India Company circa 1740s-1760s, is comparable in time, geographical location and quality to Könsberg’s note about Indian cotton fabrics below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Anders Berch Collection. NM.0017648B:71A. DigitaltMuseum). - Bomullstyger (Cotton fabrics). ‘Fine qualities, plain and striped, white and printed calicoes, Zittser, striped handkerchiefs of various quality and fineness are manufactured in Surat, Bengal and along the Coromandel coast, which together with many other commodities are brought back to Europe with the East India ships.’

- Calmink (Calamanco). ‘In multitude manufactured in Brabant, Flanders, Antwerp, Brussels, Tourneay, Tourcoin and Lannay.’

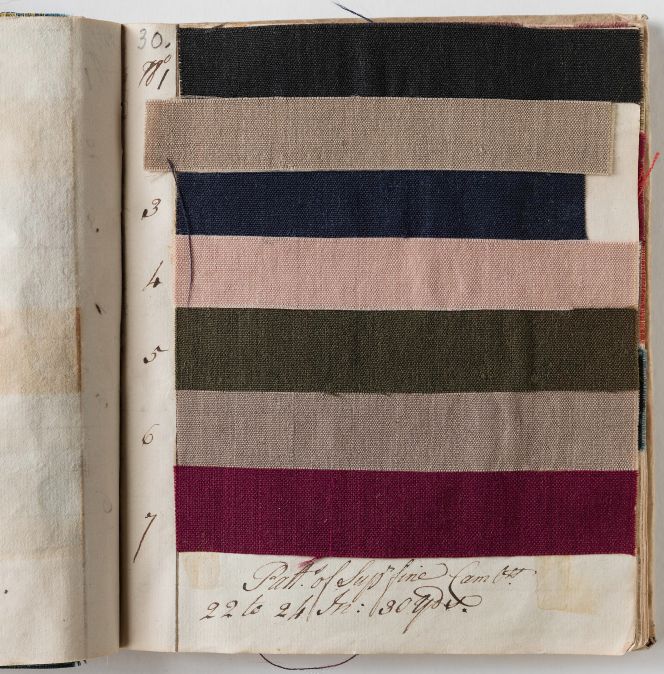

Another contemporary example from Anders Berch’s Collection – used in educational material in the mid-18th century – with Könsberg’s dictionary is this selection of English Camlets – a worsted fabric woven in tabby. According to Könsberg, this type of fabric was imported from England and other countries but was also domestically woven, as seen in the point below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0017648B:1. DigitaltMuseum).

Another contemporary example from Anders Berch’s Collection – used in educational material in the mid-18th century – with Könsberg’s dictionary is this selection of English Camlets – a worsted fabric woven in tabby. According to Könsberg, this type of fabric was imported from England and other countries but was also domestically woven, as seen in the point below. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0017648B:1. DigitaltMuseum). - Camelotter (Camlets). ‘Manufactured in many places. The Persian, the English, the ones from Brussels, and the Italian are yet most desired due to their qualities and fineness, but they are also the most costly. Our Swedish are not to despise neither, which qualities more and more are improved.’

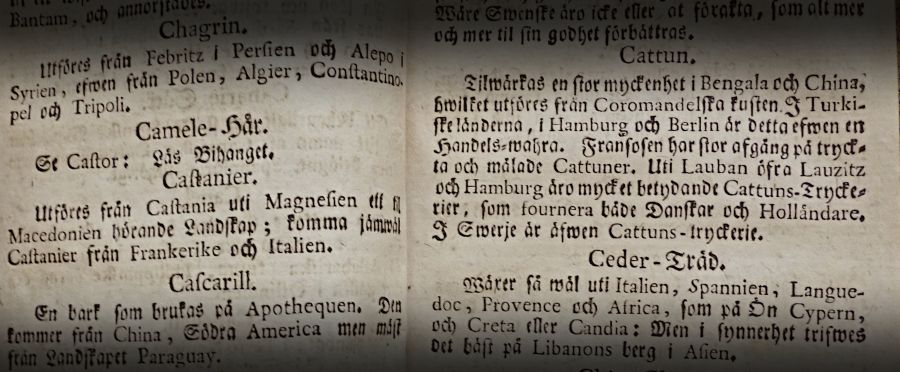

Cattun (printed calico) ‘Made in great quantity in Bengal and China, brought out from the Coromandel Coast. It is also a trading article in the Turkish lands, in Hamburg and Berlin. The French man has a great demand for printed and painted Cotton. In Lauban, upper Lauzitz and Hamburg, very significant Cotton Print mills furnish Danes and Dutchmen. In Sweden, there are also Cotton Print mills.’ (From: Könsberg…’, 1768, p. 15).

Cattun (printed calico) ‘Made in great quantity in Bengal and China, brought out from the Coromandel Coast. It is also a trading article in the Turkish lands, in Hamburg and Berlin. The French man has a great demand for printed and painted Cotton. In Lauban, upper Lauzitz and Hamburg, very significant Cotton Print mills furnish Danes and Dutchmen. In Sweden, there are also Cotton Print mills.’ (From: Könsberg…’, 1768, p. 15).- Damast (Damask). ‘Silk damask is manufactured in a great multitude in Venice, Lucca and Genua; however, the damask from Holland is of higher quality. From France in particular, as well as from Lyon and Tours, silk damask is commonly produced, but it is still not as beautiful as the Italian qualities. From China and Leipzig, Damask is also exported.’

- Drouguet (Dreadnaught/Fearnought). ‘Manufactured in great quantities in Amboise, Partenay, Viort, Reims, Rouen, Troyes, Langres and Chalongs in Champagne. In Germany, woollen dreadnaught is made. These are also manufactured in Sweden.’

- Flanell (Flannel). ‘Manufactured in Reims, Castres, Rouen and Beauvais. Printed flannels come from Hamburg, Leipzig and England; these are also manufactured rather beautifully in Sweden, just as in France.’

- Flor (Gauze). ‘The finest qualities are from Italy and Zveytz[!]. In Zyrk[!] are the most manufactured. In Lyon, France, a gauze linen manufacturer was established, which became a difficult competition for the manufacturer in Italian Bologna. A few years ago, in Berlin, a manufacturer of fine gauze linen weaving was established.’

- Hampa (Hemp). ‘Exported from Riga, Poland, Revel, Liefland and Moscow. It grows in Bayern, Westphalia, Lyneburg, Schlesien, Bretagne, Piccardie, Champagne, Bourgogne, Auvergne and Bologna too.’

Interesting paper model scene of a marketplace from the second half of the 18th century. Each market stall is opening up to sell their products from premises on the ground floor in buildings on the marketplace. Notice the drapery seller to the left and how the folded fabrics in various colours are displayed. The scene probably depicted a town in Germany, divided into many small territories or German lands at the time. Several of these territories and towns were repeatedly noted in Könsberg’s dictionary about trading goods.| This is one of the scenes in the same paper model scene cupboard. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0056107. DigitaltMuseum).

Interesting paper model scene of a marketplace from the second half of the 18th century. Each market stall is opening up to sell their products from premises on the ground floor in buildings on the marketplace. Notice the drapery seller to the left and how the folded fabrics in various colours are displayed. The scene probably depicted a town in Germany, divided into many small territories or German lands at the time. Several of these territories and towns were repeatedly noted in Könsberg’s dictionary about trading goods.| This is one of the scenes in the same paper model scene cupboard. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0056107. DigitaltMuseum).- Näsdukar (Handkerchiefs). ‘Manufactured rather beautiful in Sweden. In Leipzig, handkerchiefs are both woven of silk and half-silk. Beautiful cotton handkerchiefs are imported from Bengal.’

- Plys (Plush). ‘Some people state that the Englishmen, others that the Dutch have invented the art to manufacture plush. Nowadays, it is manufactured in Amiens, Abvenille, Compagne, Lyon and Flanders, in particular in Brussels. In Germany, in the districts where velvet manufacturing exists, like in Leipzig, Berlin, Hamburg, etc., plush is also manufactured.’

- Sammet (Velvet). ‘Manufactured in Meiland, Genua, Venice, Florence, Lucca, Lyon, Harlem, Hamburg, Leipzig, Berlin and China.’

- Spansk ull (Spanish wool). ‘This is of various fineness and quality: The provinces with the largest abundance are New and Old Castile, Aragon and Navarra. The wool of all sorts from Saragossa is even now the rarest and most in-demand.’

- Strumpor (Stockings). ‘Manufactured of a great many sorts in Sweden. Holland has three good stocking manufacturers: Harlem, Leyden, and Amsterdam. In Paris, Dourdan, Bouen, Nantes, Caen Toulouse, Nismes, Bourges, Amiens and Reims are famous stocking manufacturers. Stockings are woven in immense multitudes in Dresden, Naumburg, Denmark, Switzerland, Magdeburg, Iceland and Berlin.

Carl Magnus Könsberg’s dictionary also listed French laces from several districts among other European lace centres. He noted the following about Spetsar [Laces]: ’Made in Antwerp, Brussels, Mechelen, Löven, Gent, Brabant, Flanders, Valenciennes, Arras, Hennegau, Artois, Dieppe, Havre de Grace, Honfleur, Harfleur, Caen, Picardie, S. Denis, Champagne, Lottringen, Schwarzenberg, Eibenstock, Annaberg, Aberdam, Joachims thal, Altenberg, Husum, Tönningen and Holstein…Black silk laces are made in Italy and are sent from Verona and Roveredo’.

For additional search words related to the textile trade, the dictionary also listed the following goods:

- Alun (Alum) | Camelehår (Camel/Angora goat hair) | Conchenille (Cochineal) | Eider-dun (Eiderdown) | Färge-gräs (Dyer’s grasses) | Fjäder (Feather) | Galloner (Gold or silver Braid) | Galläpple (Oak-apple) | Garn (Yarn)| Hårtäcken (Covers made of hair) | Indigo (Indigo) | Kammarduk (Cambric) | Kardor (Carding-combs) | Lin-Garn (Flax yarn) | Lin och linfrö (Flax and Linseed) | Lärfter (Unbleached linens) | Mattor (Rugs/Carpets) | Nettelduk (Nettle-cloth) | Nålar (Needles) | Pels-wärk (Furs) | Pot-aska (Potash) | Saffran (Saffron) | Scharlakan (Kermes) | Silke (Silk) | Tapeter (Wall coverings/Tapestries) | Tysk ull (German wool) | Ull (Wool) | Wåd eller Weide (Woad).

Together with an appendix of goods manufactured, grown in plantations or raw material further developed – like imported Angora goats and camel hair – for the trade of desired products within Sweden:

- Angora Getter (Angora Goats) | Dräll (Diaper) | Färgväxter (Dye plants) | Får (Sheep) | Garn (Yarn) | Getter (Goats) |Kamel-hår (Camel hair) | Kläden (Broadcloth) | Lin (Flax) | Linne (Linen) | Sidentyg (Silk fabric) | Spetsar (Laces) | Strumpor (Stockings) | Wax-dukar (Oilcloth) |Weide (Woad) | Ylletyger (Woollen cloth).

Note: The author of this essay has made all the English translations from the Swedish dictionary published in 1768.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 320 & 354-355).

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Förordning, Emot Yppighet och Öfwerflöd, Stockholm 1766.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Förnyade Nådige Förordning, Emot Yppighet och Öfwerflöd, Stockholm 1770.

- Könsberg, Carl Magnus, Kort anwisning på in- och utrikes handelswahror såsom apotheques saker, ädla stenar, wijner, spetserier, färg-gräs, frukter, siden, linne, ylle- och bomuls-tyger…, Nörrköping 1768.

- Lund University Library, Sweden. The Special Collections Reading Room (C.M. Könsberg’s dictionary at a research visit 2018).

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden (DigitaltMuseum: Anders Berch Collection).

- Wallenquist, Arend, Carl von Linnés lärjungar i Östergötland, Linköping 2007 (Biographical information about C.M. Könsberg (pp. 199-201).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE