ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

AN ORIGINAL UPHOLSTERY FROM 1760

– A French Silk Brocade on an English Mahogany Armchair

Among its rich interior museum displays, the David Collection in København (Copenhagen) keeps an armchair, with original woven upholstery dating to around 1760. This essay aims to look closely at the silk fabric of this particular piece of furniture, including used weaving techniques, preferred red dyes of the period, skilful designers, weavers and Lyon as the long-term centre for silk weaving. Rococo and naturalism influences are also clearly visible in this complex design. Overall, such qualities were immensely time-consuming to weave and, in combination with the expensive material, inevitably made such patterned silks very expensive to buy. To some extent, furnishing fabrics stayed longer in fashion than similarly styled luxury silks for the garments of a wealthy clientele, when lavish upholstered fabrics were supposed to last for a decade or preferably for several decades. However, this well-preserved mahogany armchair has, due to fortunate circumstances, managed to survive with its original patterned silk for more than 260 years. Even the handwoven ribbon in matching colours is still intact.

Figured silk taffeta broché also named silk brocade on a ground of cannelé simpleté or cannetillé. This plain ground with two warps, where the second warp gave the “armour-like” effect, which floats over a number of threads and binds of other threads by the weft in tabby. The structure of the tabby/plain weave is clearly visible on several places on this upholstery, in particular close to the front frame (at the bottom of the picture), where the wear and tear of the lost cannelé simpleté effect is most visible. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Figured silk taffeta broché also named silk brocade on a ground of cannelé simpleté or cannetillé. This plain ground with two warps, where the second warp gave the “armour-like” effect, which floats over a number of threads and binds of other threads by the weft in tabby. The structure of the tabby/plain weave is clearly visible on several places on this upholstery, in particular close to the front frame (at the bottom of the picture), where the wear and tear of the lost cannelé simpleté effect is most visible. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. French figured silks were popular and much admired by wealthy customers who could afford such luxury and sumptuousness in the household. It may be assumed that this armchair originally was part of a set of furniture with the same chosen quality for upholstery, whilst the vibrant crimson colour most probably had been yarn dyed with the most admired dye of the time – cochineal. This is one of the most durable natural dyes for red colours, which may explain why the armchair still up to this day only is slightly faded, even if it has been part of the permanent exhibition of this 18th century interior for more than a decade and prior to this most probably exposed to light over many more years. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

French figured silks were popular and much admired by wealthy customers who could afford such luxury and sumptuousness in the household. It may be assumed that this armchair originally was part of a set of furniture with the same chosen quality for upholstery, whilst the vibrant crimson colour most probably had been yarn dyed with the most admired dye of the time – cochineal. This is one of the most durable natural dyes for red colours, which may explain why the armchair still up to this day only is slightly faded, even if it has been part of the permanent exhibition of this 18th century interior for more than a decade and prior to this most probably exposed to light over many more years. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Generally, cochineal came to be extremely popular due to its colour-fastness, new tints of colour and the highly desirable crimson red shades, considering the small amount of dried lice that was needed. The precious dyestuff arrived in France and other countries via Cadix, like all the cochineal up until the year 1778, when the Spanish monopoly ceased. Additionally, many traders also acted as intermediaries in the global cochineal trade, which might for instance mean that the dyestuff, which had already been transported from South America to Cadix, would then be reloaded and transported to Canton or Java and ending up being shipped back to Europe via one of The European East India Companies.

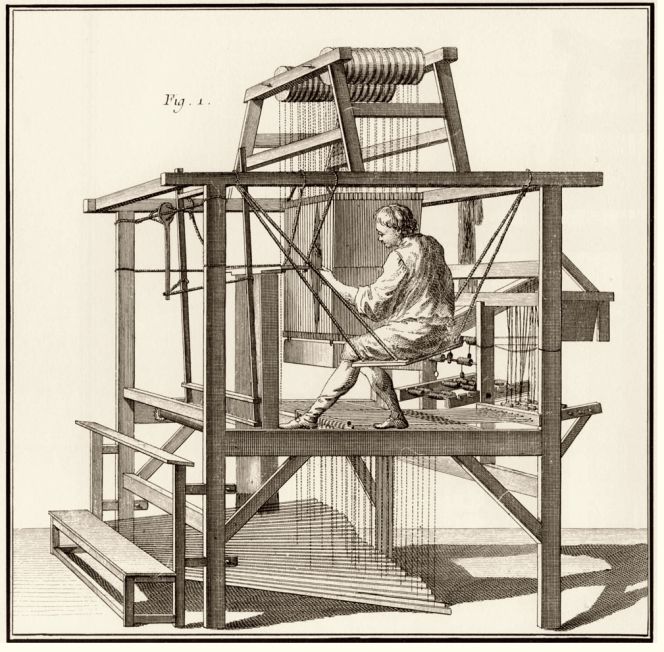

It has not been possible to make a complete technical analysis of the uniquely preserved silk fabric on this upholstered mahogany armchair, but even so, the fine quality reveals many details of historical interest. For example, the draft must originally have been drawn on graph paper, where it was marked how the multi-coloured weft threads for the patterning floated over the surface according to the design draft, which instructed the weaver as well as his assistants during the weaving process. The used loom had a draw system, where pattern heddles could be lifted individually by a “draw boy” to manage a complex brocaded patterning like the one on this armchair. The ground binding was in tabby (a red silk thread shuttled from side to side) with a supplementary weft (carried by several small shuttles as specified by the pattern design), making the front and back look different. That is to say, such a fabric had two wefts and two warps (illustrated in image one), which added to its complexity.

A master weaver’s draw-loom – like this mid-18th century depiction – was mainly used when the manufacturers wanted to produce silks with large motifs. The weaving assistant was busily preparing the very slow process to pre tie the many “draws” in preparation for the weaving to begin. The illustration is taken from the French book, Encyclopédie Vol 4, printed in 1754. (From: ’Draw-loom’. Diderot…(1754), Paris 1751-1772).

A master weaver’s draw-loom – like this mid-18th century depiction – was mainly used when the manufacturers wanted to produce silks with large motifs. The weaving assistant was busily preparing the very slow process to pre tie the many “draws” in preparation for the weaving to begin. The illustration is taken from the French book, Encyclopédie Vol 4, printed in 1754. (From: ’Draw-loom’. Diderot…(1754), Paris 1751-1772). Another book, which includes observations of French 18th century silks, was written by the Frenchman Dennis de Coetlogon (1700-1749). He moved from France to London in his youth in 1727 and in 1745 published An Universal History of Arts and Sciences. The comprehensive work contains descriptions of the most common silks and velvets of the time, illustrations of textile crafts, the commerce in silk, and information on Lyon's outstanding silk weaving. That centre for fine weaving is described as follows: ‘... and to the City of Lyons, the Reputation it still maintains, of giving the Gloss to Taffetas, better than any other City in the World’. During the 1760s – from the period when this particular silk brocade originate – the silk production was nearing its zenith at Lyon, where contemporary records, as well as modern research, show that there were about 18,000 looms active in the city in the 1780s, two thirds of which were occupied weaving the most complex designs of silk and velvet cloth. Those types of cloth were mainly used for clothes, but also had a given market as exclusive upholstery or furnishing fabrics and other interior textiles.

A few sentences may briefly focus on the history of David Collection, its founder and his long-term dedication as well as the favourable central location in the Danish capital. The foundation was established by the wealthy Danish lawyer Christian Ludvig David (1878-1960), due to his early interest in art making him to a well-renowned art collector quite early in life, with a collection which had become substantial in size during the 1930s. Fine and applied arts from the 18th century was one of his interests (which the discussed armchair is part of), together with Islamic art and Danish early modern art. This very extensive private collection, which has increased in size after C.L. David’s lifetime, is today located in one of his former properties, Kronprinsessegade no. 30 in København (Copenhagen), where he kept a museum himself opened in 1948. A property which was built already around 1807 and in the decades to follow had housed C.L. David’s great-grandfather’s family. This “snapshot” of everyday life around the year 1845 – on a watercolour by Heinrich Gustav Ferdinand Holm – depicted the Kronprinsessegade situated side by side with Kongens Have (The King’s Garden). (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

A few sentences may briefly focus on the history of David Collection, its founder and his long-term dedication as well as the favourable central location in the Danish capital. The foundation was established by the wealthy Danish lawyer Christian Ludvig David (1878-1960), due to his early interest in art making him to a well-renowned art collector quite early in life, with a collection which had become substantial in size during the 1930s. Fine and applied arts from the 18th century was one of his interests (which the discussed armchair is part of), together with Islamic art and Danish early modern art. This very extensive private collection, which has increased in size after C.L. David’s lifetime, is today located in one of his former properties, Kronprinsessegade no. 30 in København (Copenhagen), where he kept a museum himself opened in 1948. A property which was built already around 1807 and in the decades to follow had housed C.L. David’s great-grandfather’s family. This “snapshot” of everyday life around the year 1845 – on a watercolour by Heinrich Gustav Ferdinand Holm – depicted the Kronprinsessegade situated side by side with Kongens Have (The King’s Garden). (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Two further close-up detail of the silk brocade, reveal more details of the weaving of such fine qualities. Firstly, the narrow loom width of the time is clearly visible, with a fabric width of circa 50 cm, evident via that pieces of fabric were finely stitched together, noticeable on several surfaces on this upholstery. It may be observed, that some fifty years later, with the introduction of the Jacquard machine in 1804 and the development of larger looms, there were no longer any need to seam together two or more fabric pieces, like on this 1760s armchair. The matching ribbon was woven in linen with two thin silk cords and red threads as decorative features (additional warp threads) in the otherwise plain woven ribbon. Overall, ribbons formed a noteworthy component for upholstering, not only used as decoration but also to hide or reinforce seams like for this piece of furniture. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Two further close-up detail of the silk brocade, reveal more details of the weaving of such fine qualities. Firstly, the narrow loom width of the time is clearly visible, with a fabric width of circa 50 cm, evident via that pieces of fabric were finely stitched together, noticeable on several surfaces on this upholstery. It may be observed, that some fifty years later, with the introduction of the Jacquard machine in 1804 and the development of larger looms, there were no longer any need to seam together two or more fabric pieces, like on this 1760s armchair. The matching ribbon was woven in linen with two thin silk cords and red threads as decorative features (additional warp threads) in the otherwise plain woven ribbon. Overall, ribbons formed a noteworthy component for upholstering, not only used as decoration but also to hide or reinforce seams like for this piece of furniture. (Collection: David Collection in København, Denmark. No: 26/1975). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Several silk qualities of a similar kind to this French silk brocade can be studied in a unique merchant sample book from 1764, kept at Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and presented by the textile historian Lesley Ellis Miller in a folio-sized volume in 2014. Her research emphasised that: ‘French silks were extremely important indicators of taste and status in eighteenth-century Europe, whether acquired legally or illegally.’ A luxurious fabric like the one on the well-preserved mahogany armchair was part of the more expensive range, even if qualities including metal threads of gold and silver were even costlier. This publication gives plenty of examples for such designs of bouquets of flowers scattered across the surface with meandering white coloured lace like structures, not seldom with a three-dimensional impression constructed by the flowery design, weaving technique and the more heavily structured woven ground.

It must also be stated that the multitude of design variations of French 18th century silks appears to have been exceptional – uniqueness was highly desirable – which makes it rare to discover exactly the same fabric. Either compared to sample books or on artwork via depicted clothing and furnishing or on extant upholstered furniture or garments. This mahogany armchair created by multiple craftsmen is no exception. Even if many historical facts have been enlightened, my observations were not able to pinpoint an exact match for this 1760s silk design.

Notice: All reasonings about this original upholstery have been made via my research of comparable fabrics, closeup study of the armchair, etc. The museum display only informs about ‘Armchair of Mahogany, England, c. 1760’. | The next essay will be a follow-up and focus on two chairs and one sofa with embroidered upholstery, dating to 1730s-1760s in England – part of the same interior at the David Collection in Copenhagen.

Sources:

- Coetlogon, Dennis, de, An Universal History of Arts and Sciences, London 1745 (pp. 1202-1207).

- David Collection in København, Denmark. (Exhibition: European 18th-Century Art. Armchair of mahogany, England, ca. 1760, No: 26/1975. | Research visits in Febr. 2020 & Sept. 2021). & General historical information about the David Collection on the museum website.

- Diderot, Dennis ed., Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Paris (Vol. Four 1754), 1751-1772.

- Design Museum, København, Denmark. (The Library: research visit in February 2020).

- Geijer, Agnes, A History of Textile Art, London 1982 (Silk Weaving in Europe, France, pp. 153-161).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 255-256 & 316).

- Miller, Lesley Ellis, Selling Silks: A Merchant’s Sample Book 1764, London 2014. (Quote: p. 12).

- Peck, Amelia, ed., Interwoven Globe – The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, New York 2013. (Facts about the Spanish monopoly of cochineal p. 122).

- Rothstein, Natalie, Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century, London 1990.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE