ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

BANYANS AND OTHER GARMENTS

– Reflections of Natural Knowledge, Trade and Clothes in 18th Century Libraries

The Japanese gown was part of long-distance global trade during the 17th century. A comfortable garment which initially became popular to wear at home by Dutchmen, who had direct access to Japanese trade via the Dutch East India Company. It became a luxurious fashion, visible in portraits during at least a hundred fifty year-long period, not only portraying wealthy men in Amsterdam and Leiden, but it was soon introduced to other Europeans as well as immigrating merchants who had settled in the North American colonies. The garment was known as gown or robe or banyan, and among many matters, it can be linked to naturalists and other individuals in library interiors. This essay will give a glimpse into this cosmopolitan world during the 18th century – researched via portraits, prints, preserved silk gowns and observations in travel journals by three of the so-called Linnaeus Apostles.

The Dutch merchants, historians, poets et al. were frequently portrayed in such a garment during the second half of the 17th century, whilst some continued to be so in the coming century, like in this portrait of the author Hendrik Snakenburg (1674-1750) circa 1716. His high standard of living was chosen to be illustrated in a domestic sphere, most probably set in his private library. The display of wealth is not only demonstrated via the many leather and parchment-bound volumes, a small marble table with a gilded foot by the window, an inkstand set of silver etc., but also his fine clothing. This is visible in his linen shirt and particular via a voluminous banyan, which seems to have been stitched from a shiny silk quality and judging by the green lining, it was padded with carded silk or cotton raw material to become warmer and more comfortable. | Oil on panel by Hieronymus van der Mij. (Courtesy: Museum de Lakenhal, Leiden, The Netherlands. No. S 331).

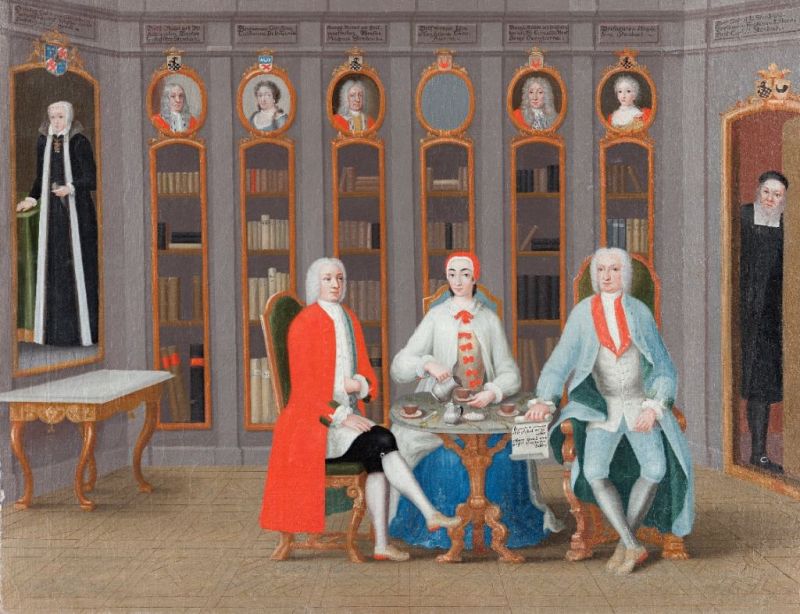

The Dutch merchants, historians, poets et al. were frequently portrayed in such a garment during the second half of the 17th century, whilst some continued to be so in the coming century, like in this portrait of the author Hendrik Snakenburg (1674-1750) circa 1716. His high standard of living was chosen to be illustrated in a domestic sphere, most probably set in his private library. The display of wealth is not only demonstrated via the many leather and parchment-bound volumes, a small marble table with a gilded foot by the window, an inkstand set of silver etc., but also his fine clothing. This is visible in his linen shirt and particular via a voluminous banyan, which seems to have been stitched from a shiny silk quality and judging by the green lining, it was padded with carded silk or cotton raw material to become warmer and more comfortable. | Oil on panel by Hieronymus van der Mij. (Courtesy: Museum de Lakenhal, Leiden, The Netherlands. No. S 331). A somewhat later example dated to circa 1740, portrayed ’The Stenbock family in their library at Rånäs’, situated close to Stockholm in Sweden. This household library interior is enlightening from several perspectives. The global cultures, luxury consumption and affluent living conditions are partly demonstrated in a similar way as on the image above. All three individuals wore robes/modified banyan style garments, for warmth in their high-ceiling library. In particular the lady’s floor-length white garment, tied with a red ribbon at the neck, seems to have been made in a comfortable wide model. The gentlemen’s lined garments were more close-fitting in the style of a collarless coat with deep cuffs. Further attributes of wealth include: drinking of chocolate or coffee, seated on high-back upholstered chairs in front of decorated bookshelves at the same time as their ancestors’ portraits looked down on the daily life. Whilst the clergyman who peeked into the room, probably symbolised their Christian devoutness equally as he may have kept an observing eye, so the noble family stayed within moderation even for their higher strata of society. | Oil on canvas by Carl Fredrik Swan (1708-1766). (Courtesy: Skokloster Castle, Sweden. No: SKO3053. Wikimedia Commons).

A somewhat later example dated to circa 1740, portrayed ’The Stenbock family in their library at Rånäs’, situated close to Stockholm in Sweden. This household library interior is enlightening from several perspectives. The global cultures, luxury consumption and affluent living conditions are partly demonstrated in a similar way as on the image above. All three individuals wore robes/modified banyan style garments, for warmth in their high-ceiling library. In particular the lady’s floor-length white garment, tied with a red ribbon at the neck, seems to have been made in a comfortable wide model. The gentlemen’s lined garments were more close-fitting in the style of a collarless coat with deep cuffs. Further attributes of wealth include: drinking of chocolate or coffee, seated on high-back upholstered chairs in front of decorated bookshelves at the same time as their ancestors’ portraits looked down on the daily life. Whilst the clergyman who peeked into the room, probably symbolised their Christian devoutness equally as he may have kept an observing eye, so the noble family stayed within moderation even for their higher strata of society. | Oil on canvas by Carl Fredrik Swan (1708-1766). (Courtesy: Skokloster Castle, Sweden. No: SKO3053. Wikimedia Commons).Other contemporary connections to libraries and banyans can, with advantage, be studied via three of the naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) students or so-called apostles, who gave detailed observations and information in their written journals about libraries from a natural history perspective during their long-distance travels. Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), during his North American journey between 1747-51, sailed from Göteborg, via the Norwegian coastal towns, to England, where he made several visits to the elderly Hans Sloane (1660-1753) in London. On 28 April in 1748, Kalm noted in his journal the following about the unimaginable large library:

- ‘Sir Hans Sloane’s incomparable library, which is said to be matched by few among private ones assembled by a single man and consists of somewhat more than 48,000 volumes, all bound in splendid bindings.’

Pehr Kalm, mentioned libraries several times too during his years in the North American colonies. For instance, shortly after his arrival in Philadelphia on 16 September 1748, he noted that people in town could subscribe and, in that way, get access to books, most of these in English, French and Latin. Money raised in this manner was employed for the salary of the librarian and for purchasing new books. Somewhat more than a year later, when Kalm had returned back to Philadelphia over the winter period, he gave a most enlightening description of local libraries, the overseas expansion of such establishments and how closely linked to science these libraries seem to have been. On 21 November 1749, the travel journal stated:

- ‘The library in this town was established a few years ago. Mr Franklin was one of the first to lay the basis for it and instigated its creation; a number of ‘gentlemen’ then joined together and each donated 40 shillings for the purchase of books, so that they then had 100 pounds with which to buy books; those who now run this library each give enough to provide 50 pounds with which to buy books every year; a number of others in this town have followed their example, and several libraries have now been established here, from which one may borrow books for a small charge; a wealthy gentleman came here from Rhode Island; when he saw how it was organised, he liked it so much that on his return home he persuaded a number of gentlemen in Rhode Island to construct a building for a library, while he on his part donated 500 pounds sterling to purchase books for it. For the library here in Philadelphia the proprietor Penn has given land on which to construct a building for it, glass-tubes, a machine for generating electricity, two globes, etc.’

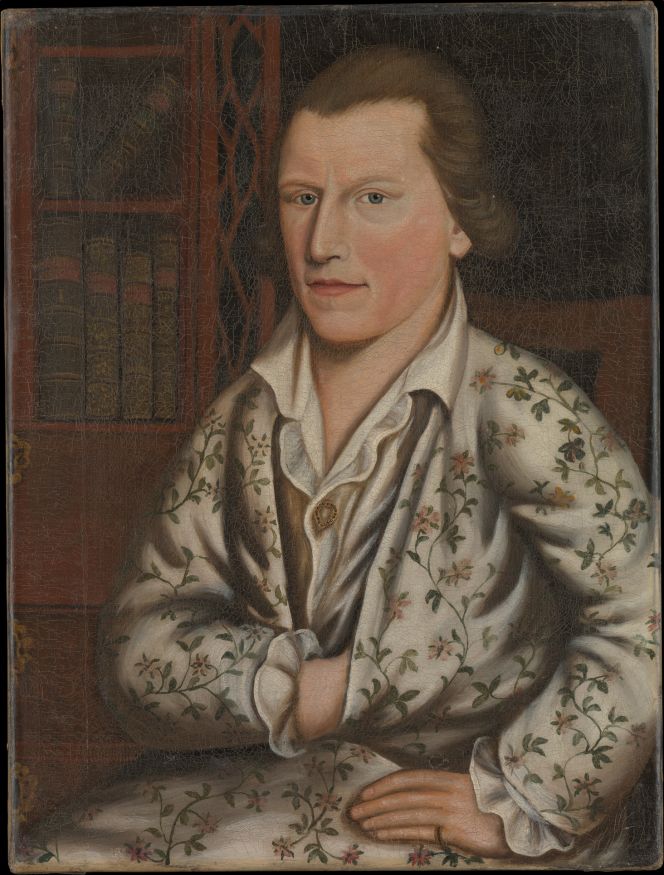

It is likely that banyans had crossed the Atlantic in the trunks of their owners prior to the mid-18th century, but such silk garments were in any case not mentioned by Pehr Kalm in his exhaustive travel journal. This somewhat later portrait of the Scottish immigrant textile importer William Duguid (1747-?) however, depicted a man based in Boston, Massachusetts in 1773, who preferred such a loose-fitting style of dress in his library, probably modest in size due to the small number of volumes visible in the cupboard-cum-bookshelves. Over his ruffled linen shirt, he wore a fine banyan, which was made of straight cut fabric pieces of a high-quality chintz (printed cotton) of either a European or Indian manufacture. | Oil on canvas by the artist Prince Demah Barnes of African descent (?-?). (Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collections. Friends of the American Wing Fund, 2010. No: 2010.105. Public Domain)

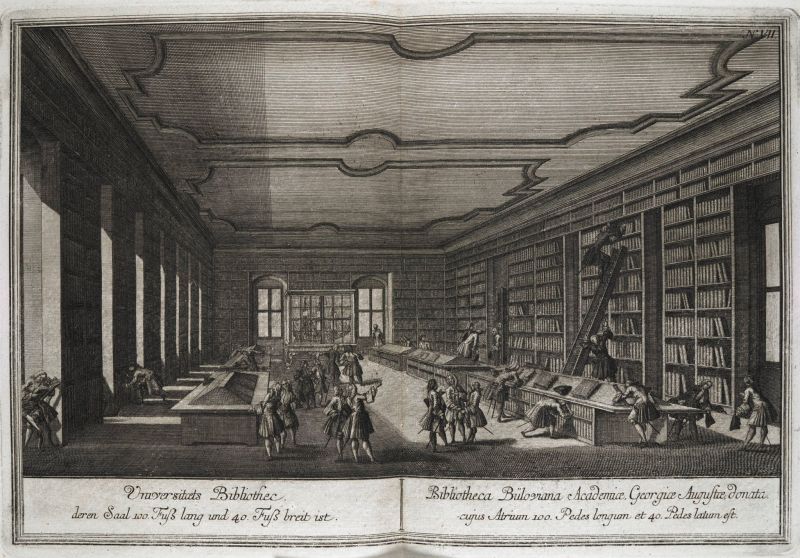

It is likely that banyans had crossed the Atlantic in the trunks of their owners prior to the mid-18th century, but such silk garments were in any case not mentioned by Pehr Kalm in his exhaustive travel journal. This somewhat later portrait of the Scottish immigrant textile importer William Duguid (1747-?) however, depicted a man based in Boston, Massachusetts in 1773, who preferred such a loose-fitting style of dress in his library, probably modest in size due to the small number of volumes visible in the cupboard-cum-bookshelves. Over his ruffled linen shirt, he wore a fine banyan, which was made of straight cut fabric pieces of a high-quality chintz (printed cotton) of either a European or Indian manufacture. | Oil on canvas by the artist Prince Demah Barnes of African descent (?-?). (Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collections. Friends of the American Wing Fund, 2010. No: 2010.105. Public Domain) A library interior from the Georg-August University in Göttingen 1745, which was ‘100 feet long and 40 feet wide’ where the male students, teachers and librarian(s) were depicted in traditional upper-class fashion of the day with a three-piece suit (coat, waistcoat and breeches), white silk stockings and buckled shoes. This is a good illustrative comparison on the aspect of clothes in private versus university/public libraries. Banyans or various silk gowns are not visible here, or on other similar prints, so such informal garments seem to have been preferred in private libraries only. Another interesting connection is that the former Linnaeus’ student Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) must have visited this particular library many times as he studied at the Georg-August University from 1753-56 for the philosopher and naturalist Samuel Christian Hollmann (1696-1787) et al. | Engraving by the German draughtsman and printmaker Georg Daniel Heumann (1691-1759). (Courtesy: British Library, London, UK. General Reference Collection 118.d.5. No: BLL01017754896. Etching and engraving; 22 x 33 cm).

A library interior from the Georg-August University in Göttingen 1745, which was ‘100 feet long and 40 feet wide’ where the male students, teachers and librarian(s) were depicted in traditional upper-class fashion of the day with a three-piece suit (coat, waistcoat and breeches), white silk stockings and buckled shoes. This is a good illustrative comparison on the aspect of clothes in private versus university/public libraries. Banyans or various silk gowns are not visible here, or on other similar prints, so such informal garments seem to have been preferred in private libraries only. Another interesting connection is that the former Linnaeus’ student Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) must have visited this particular library many times as he studied at the Georg-August University from 1753-56 for the philosopher and naturalist Samuel Christian Hollmann (1696-1787) et al. | Engraving by the German draughtsman and printmaker Georg Daniel Heumann (1691-1759). (Courtesy: British Library, London, UK. General Reference Collection 118.d.5. No: BLL01017754896. Etching and engraving; 22 x 33 cm). During Peter Forsskåls’ somewhat later long-distance journey, Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia), which began on 7 January 1761, his interest in learning from a historical perspective is evident via his diary. In particular, from his time in Egypt, when he wrote down some thoughts about libraries linked to Classical antiquity. For instance, on 11 October the same year from Alexandria:

- ‘This place is of great importance in the history of learning if it is true that the Athanasian library, which is said to have been an exceptionally large collection, still exists here in the care of this heretical faith having been temporarily lost in the interim. At the very least these writings would provide a priceless addition to our understanding of the history of earlier times and of much more; not only that, but local people believe we should double our estimate of the size of its collection by including works rescued from the famous Ptolemaic library.’

Forsskål did not get more opportunities to deepen his interest in the former famous ancient libraries of Alexandria (which at least had existed already in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC), due to that the young Linnaeus’ apostle sadly died of malaria further on during the journey in Yemen on 11 July 1763 – at the age of 31.

Whilst the naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828), who had the fortune to live to an old age, in the 1770s took great advantage of several European libraries, during the start and end periods of his nine-year-long natural history journey to southernmost Africa, Java, Japan and other places. As a former student of Carl Linnaeus, who also had visited Johannes Burmann (1707-1780) already in 1735, eased Thunberg’s introduction to the most prestigious botanical networks and he made good use of Burmann’s library as well as his cabinet of natural history. ‘Here I perceived the unspeakable advantage of a professor having a library so near at hand, which affords him an opportunity of arranging it in scientific order, and of comparing the different subjects in his collection with the figures and descriptions of different authors, of which it is frequently necessary to consult, not only one or two, but a hundred’ (18 Oct. 1770). Further quotes from Amsterdam, Leyden, Paris and London give more detailed information into the learned natural knowledge via books as Thunberg registered in his travel journal.

- 9 October 1770, Amsterdam. | ’I visited the Professors, Messrs. Burmanns, who received me in a very friendly manner. In my daily visits to them, I had not only the pleasure of surveying their different and numerous collections in natural history, and the advantage of their valuable library, in which the late celebrated Linnaeus put the last hand to his Bibliotheca Botanica, but was likewise invited every day to their tables, and requested to examine and give names to a great number of unknown minerals, insects, and plants, particularly of the grass and moss kind.’

- 16 October 1770, Leyden. | ’The houses at Leyden have the same external appearance as at Amsterdam, but have no sunk storeys. The edifice of the university is divided into separate apartments or lecture- rooms; the chairs are small, and there are benches with desks before them for the students. The library is neat, though neither large nor much decorated. Immediately under it, is the anatomical theatre.’

- 14 December 1770, Paris. | ‘I viewed the convent of St. Genevieve, its library, cabinet of natural history, and fine gardens. The library is in the uppermost storey, in the form of a cross, having bookcases all round the sides, and under the windows: the doors of the bookcases are of wire-work, and secured with locks. The books are all numbered. Between each bookcase is placed the picture of some monarch or philosopher. The library is open on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, from two till five in the afternoon, and books may be borrowed from it. The cabinet of antiquities, and that of natural history, are contiguous to the library, and contain several amphibious animals and fishes stuffed, mummies, minerals, shells, and corals, but especially a great number of antiquities, all locked up within wire-work’.

- January 1779, London. ‘The Library, which Sir Joseph Banks has collected, is in fact the completest in the world, with respect to Natural History, both in old and new works. It is erected in a large separate room, before you enter into the Cabinet, by means of which one has a most incomparably fine opportunity, when one is examining any particular plant, of referring to, and consulting whatever author one chooses, without loss of time, and without being under the necessity of fetching books from a general Library, which frequently stands at a great distance off, and is most commonly incomplete, and not always accessible.’

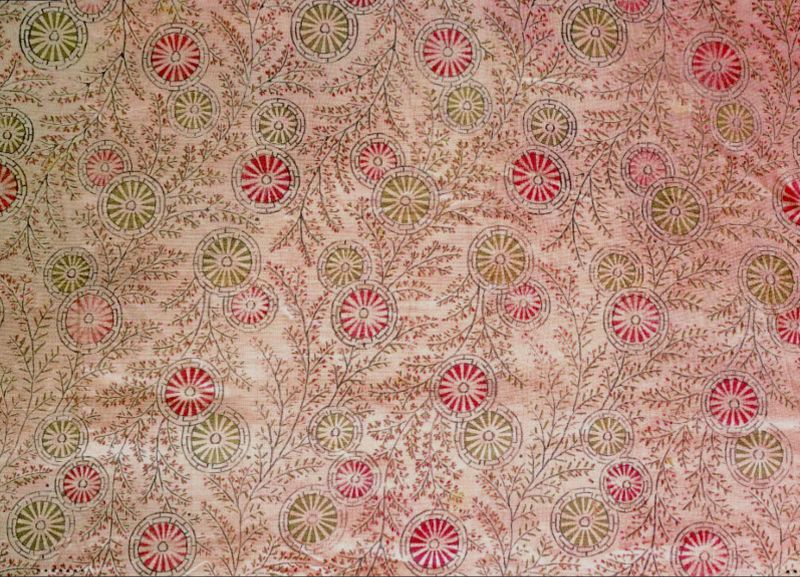

Still, during the mid-1770s, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) regarded the Japanese silk gowns and other fine fabric qualities as valuable via gifts or barter goods at the stop-over in Japan. The importance of these garments is particularly evident via Carl Peter Thunberg’s travel journal in May 1776. On two occasions, he was presented with gifts of a textile nature during the 26-day-long stay at Jedo/Edo (today Tokyo). The first one consisted of a very unusual fabric, described as follows: ‘It was woven, was as white as snow, and resembled calico; but it was prepared, spun, and woven, from the same kind of bark and its filaments of which their paper is commonly made. This was used instead of linen, not through necessity, but as a rarity, and was not very strong. It was said that it would bear washing, but that this operation was to be performed with great care.’ One of the highlights during the visit in the town was the audience with the emperor and the heir apparent, which took place before their departure. On that occasion, all persons of rank such as officers, ambassadors and governors were presented with costly gifts, consisting of the finest conceivable silk nightgowns; the greater the number, the higher ranking of the recipient. The number varied from ten to two gowns, Thunberg and the accompanying secretary receiving two, some being saved on behalf of the Company, while the Dutch ambassador was honoured with four gowns. All of the garments were made of the finest Japanese silk, of ankle-length and with wide sleeves, in accordance with Japanese dress tradition. Besides, the plain or flowery silks were utterly exquisite, quilted with either silk or cotton wadding.

After Thunberg’s return back to Uppsala in 1779, a few notes in newspapers the following year give further details about these silk gowns, which at this point was part of his Japanese collection. According to research by historian Marie-Christine Skuncke, Thunberg, among other matters, had arranged some sort of Royal entertainment in Uppsala, when the Baron Eric Oxenstierna as part of the distinguished company was ‘dressed in Japanese clothes, sitting in the Japanese way’. A notice which had been printed in Stockholms lärda tidningar on 24 July 1780.

However, to my knowledge, it is unknown if Carl Peter Thunberg used these finely quilted silk garments for his own private use at home over the years. Likewise as it is uncertain when he initially donated the Japanese silk gowns to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or another early museum collection, but it was part of the ‘Uppsala Collection’ for many years. Today the Japanese objects are kept at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, just as several of the other collections amassed by Carl Linnaeus’ travelling apostles around the world. This close-up detail is taken from one of the nightgowns, which was brought back from Japan by Thunberg as well as mentioned in his travel journal. The wadded garment – has a printed wheel motif with floral garlands – on a plain woven silk. (Courtesy: Thunberg Collection, Museum of Ethnography, Sweden. no.1874.1.87).

However, to my knowledge, it is unknown if Carl Peter Thunberg used these finely quilted silk garments for his own private use at home over the years. Likewise as it is uncertain when he initially donated the Japanese silk gowns to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or another early museum collection, but it was part of the ‘Uppsala Collection’ for many years. Today the Japanese objects are kept at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, just as several of the other collections amassed by Carl Linnaeus’ travelling apostles around the world. This close-up detail is taken from one of the nightgowns, which was brought back from Japan by Thunberg as well as mentioned in his travel journal. The wadded garment – has a printed wheel motif with floral garlands – on a plain woven silk. (Courtesy: Thunberg Collection, Museum of Ethnography, Sweden. no.1874.1.87).

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (The Travel Journals of: Vol. Three: Pehr Kalm. Vol. Four: Peter Forsskål & Vol. Six: Carl Peter Thunberg).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Chapters of Pehr Kalm, Peter Forsskål & Carl Peter Thunberg).

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & Vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Peck, Amelia, ed., Interwoven Globe – The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, New York 2013 (pp. 291-92).

- Skuncke, Marie-Christine, Carl Peter Thunberg: Botanist and Physician, Uppsala 2014 (pp. 197 & 325).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE