ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

BLUE OR GREEN WOOLLEN COATS

– a Case Study of Farmers and Hunters in 18th century Sweden

Blue or green woollen coats were two of many variations of justaucorps or knee-length coats suitable for various everyday and festive occasions. A practical and warm garment worn by “ordinary” men, which were inspired by military clothing as well as more lavish designs made from luxurious fabrics preferred by a small group of wealthy aristocrats et al. This essay is based on a selection of 18th century primary sources – including dove-tail tapestries woven in farming communities, broadcloth samples, preserved garments, artwork, as well as travel journals and some further local observations made by the naturalists Carl Linnaeus and Pehr Osbeck in Sweden. Other aspects briefly looked into will be the weaving, dyeing and teasing of such woollen qualities and many other skilled processes before the broadcloth could be used for garments.

This genre painting by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) dating circa 1780 shows a hay-harvest festival at the castle Svartsjö at Ekerö, close to Stockholm. Many of the celebrating farmers wore bluish-green or grey justaucorps style woollen coats. Whilst the spectators of the noble community, at this period seems to have preferred the so-called National Costume introduced by Gustav III (1746-92) in 1778 (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm NM.0261301. Digitalt Museum).

This genre painting by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816) dating circa 1780 shows a hay-harvest festival at the castle Svartsjö at Ekerö, close to Stockholm. Many of the celebrating farmers wore bluish-green or grey justaucorps style woollen coats. Whilst the spectators of the noble community, at this period seems to have preferred the so-called National Costume introduced by Gustav III (1746-92) in 1778 (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm NM.0261301. Digitalt Museum). Karl XII was one of the Swedish kings along with other military men of the late 17th- and early 18th centuries who wore dark blue justaucoups, which this larger than life-size oil on canvas demonstrates – attributed to the artist David von Krafft (1655-1724). The text reads in translation: ‘King Carl the XII. In this way he was dressed when doing his campaign in the year 1700’. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. No. NMGrh 1267. Public Domain).

Karl XII was one of the Swedish kings along with other military men of the late 17th- and early 18th centuries who wore dark blue justaucoups, which this larger than life-size oil on canvas demonstrates – attributed to the artist David von Krafft (1655-1724). The text reads in translation: ‘King Carl the XII. In this way he was dressed when doing his campaign in the year 1700’. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. No. NMGrh 1267. Public Domain).This style of upper garment – in a somewhat altered model – was commonly used by the country people in many provinces of Sweden later in the century, as illustrated in the images above and below. Practical use of clothes, traditions, sumptuary laws, fashion preferences, accessibility to suitable cloth, skilled dyers and a multitude of other local factors often make it hard to give exact evidence for how, when and where inspirations took place for a particular garment. Gradual shifts linked the wealthy strata of society to military uniforms, townsmen, tailors, and the dominating group in society – the farmers. Everyday meetings and random encounters between these groups of people over decades or even over a century a more, influenced clothing and made some traditions to stay popular for shorter or longer periods in different geographical areas. However, research by the late historian Anna-Maja Nylén shows that the widespread use of justaucorps in the farming community at this time had an unusually well-documented history. She noticed the direct contact in a widespread area via Karl XI’s (1655-1697) and Karl XII’s (1682-1718) soldiers: ‘Through Karl XI’s army reform the country was divided into small sections, which each and everyone should be responsible for its soldier’s upkeep and clothing according to regulations of the uniform. At the time when the division took place during the 1680s and the uniform was decided, it became inspired by the French fashion with tight-fitting breeches and knee-length justaucorps with tail-slits and large pockets with pocket flaps, sleeve lapels and buttons.'

This blue woollen coat originates from the district of Höök in the province of Halland where Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) worked as a rector in the parish of Hasslöv, and it is undoubtedly the kind of men’s wear which was recorded in his notes of the area from the end of the 18th century, both in terms of its blue colour and the fact that it buttoned down the front with silver buttons. The conclusion is reinforced further through the information on the museum catalogue card, which shows that the coat had been made between 1775 and 1825 and is described as ‘a Man’s coat of the justaucorps type, of 18th century fashion. Of mid-blue wadmal, woven in 3/1 twill’ (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. 0053550. Digitalt Museum).

This blue woollen coat originates from the district of Höök in the province of Halland where Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) worked as a rector in the parish of Hasslöv, and it is undoubtedly the kind of men’s wear which was recorded in his notes of the area from the end of the 18th century, both in terms of its blue colour and the fact that it buttoned down the front with silver buttons. The conclusion is reinforced further through the information on the museum catalogue card, which shows that the coat had been made between 1775 and 1825 and is described as ‘a Man’s coat of the justaucorps type, of 18th century fashion. Of mid-blue wadmal, woven in 3/1 twill’ (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. 0053550. Digitalt Museum).During his many years in the parish of Hasslöv, Pehr Osbeck could hardly avoid seeing the changes in the parishioners’ way of dressing. It was principally their festive garb that interested him, whilst the everyday clothes presented fewer variations. It was not only the styles that changed, but the colours and materials differed too. For the men, the novelty was that in 1758, they had mainly worn grey homespun, whereas 40 years on, they dressed in blue adorned with silver buttons and wore hats with velvet ribbons, silk braid and fur coats, as he mentioned in his description of the area in 1796.

Although manufacture made fabrics generally increased during the 18th century, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) – among other contemporary making notes about such traditions – nonetheless showed an interest in the manufactured textiles out of all proportion in comparison with home-crafted articles; particularly bearing in mind that the production of the manufactures only formed a modest percentage as compared to the febrile activity going on in the homes in the form of weaving, embroidering, knitting, employing a number of textile techniques. Weaving for the household’s own needs prevailed all over the country, mainly textiles necessary for the beds and clothes – like woollen cloth which after a fulling process either became broadcloth or the coarser wadmal, both equally suitable for warm and practical coats.

As an example of manufacture woven broadcloth used for coats and a variety of garments, the Annual Report of Kommerskollegium in 1751 has been looked at more closely. Here illustrated with the weaving manufacturer ‘Master Mich: Obbarius’ who had produced dark blue broadcloths among other woollen qualities like damask, twills, printed and ribbed fabrics this year. Johan Michael Obbarius was the owner of one of the larger businesses in Stockholm with 40 looms. According to Sven T. Kjellberg’s in-depth research, Obbarius and some other master weavers in the capital also had difficulties to find skilled weavers. Due to this reality, recruiting agents were hired to find suitable weavers abroad. In 1752 for instance, workers came from Westfalen, Holland, Achen, Danzig, Limburg etc. Beside the looms, the ideal establishment for such a textile manufacturer included magazines for keeping oils, dyestuff, various sorts of wool etc, as well as a magazine for ready-made wares. Together with useful buildings like a wool sorting house, washing house, weaving rooms, a broadcloth stamp and other equipment for the processes of fulling, teasing and cutting the cloth, dye-works and drying frames – preferably outdoors or on a warm attic. (Collection: The National Archive, Stockholm). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

As an example of manufacture woven broadcloth used for coats and a variety of garments, the Annual Report of Kommerskollegium in 1751 has been looked at more closely. Here illustrated with the weaving manufacturer ‘Master Mich: Obbarius’ who had produced dark blue broadcloths among other woollen qualities like damask, twills, printed and ribbed fabrics this year. Johan Michael Obbarius was the owner of one of the larger businesses in Stockholm with 40 looms. According to Sven T. Kjellberg’s in-depth research, Obbarius and some other master weavers in the capital also had difficulties to find skilled weavers. Due to this reality, recruiting agents were hired to find suitable weavers abroad. In 1752 for instance, workers came from Westfalen, Holland, Achen, Danzig, Limburg etc. Beside the looms, the ideal establishment for such a textile manufacturer included magazines for keeping oils, dyestuff, various sorts of wool etc, as well as a magazine for ready-made wares. Together with useful buildings like a wool sorting house, washing house, weaving rooms, a broadcloth stamp and other equipment for the processes of fulling, teasing and cutting the cloth, dye-works and drying frames – preferably outdoors or on a warm attic. (Collection: The National Archive, Stockholm). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London. This wallpainting dated to the 1770s at Högbo Works in the province of Gästrikland, further demonstrates that the tradition to wear a blue woollen coat by farmers, hunters et al had a similar use in a large geographical area, stretching over at least 800 kilometres in Sweden. Like on this depiction of ‘Hunter with dog’, blue often seems to have been the preferred colour, but Carl Linnaeus observed the advantage with green shades in his journal from the Skåne Journey in 1749. Before reaching this southerly province, he stopped at various places in southern Småland to make observations. On 10 May in the parish of Bergkvara, where he noted: ‘The shooter is wearing green clothes and a green cap, so the birds will not notice him’. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NMA.0048066, part of. Digitalt Museum).

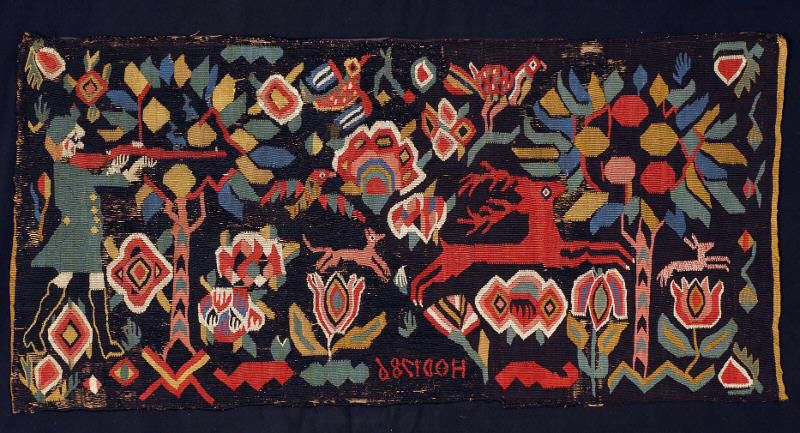

This wallpainting dated to the 1770s at Högbo Works in the province of Gästrikland, further demonstrates that the tradition to wear a blue woollen coat by farmers, hunters et al had a similar use in a large geographical area, stretching over at least 800 kilometres in Sweden. Like on this depiction of ‘Hunter with dog’, blue often seems to have been the preferred colour, but Carl Linnaeus observed the advantage with green shades in his journal from the Skåne Journey in 1749. Before reaching this southerly province, he stopped at various places in southern Småland to make observations. On 10 May in the parish of Bergkvara, where he noted: ‘The shooter is wearing green clothes and a green cap, so the birds will not notice him’. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NMA.0048066, part of. Digitalt Museum). The use of justacourps style garments by hunters, here in a faded greenish blue colour – originally green – was also included in this dove-tail tapestry woven carriage cushion marked ‘HOD 1786’ in reverse. This rare combination of motifs on a linen warp and woollen weft, with its hunting scene was probably woven in a one of the western districts of the most southerly province Skåne in Sweden (Courtesy: Kulturen in Lund. KM 57994, Digital source).

The use of justacourps style garments by hunters, here in a faded greenish blue colour – originally green – was also included in this dove-tail tapestry woven carriage cushion marked ‘HOD 1786’ in reverse. This rare combination of motifs on a linen warp and woollen weft, with its hunting scene was probably woven in a one of the western districts of the most southerly province Skåne in Sweden (Courtesy: Kulturen in Lund. KM 57994, Digital source).Additionally, dyeing blue was more complex than, for instance, yellow, brown or red, not only because the process with vat-dyeing was so much more intricate, but also because there was, in fact, only one plant in Sweden which yielded blue dye, woad (Isatis tinctoria). That dye plant and the imported indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), in the main via colonial and East India trade networks, were the two dyestuffs which were used in parallel in 18th century Sweden. However, still with the balance on the side of the domestic woad; but woad was also imported to cover the country’s demand as described by Carl Linnaeus in his journal from the Västergötland Journey in 1746. Natural dyeing of a “true green” colour, however, is not possible to produce whilst using only one single plant; dyeing has to be done twice, first yellow and then using a blue dyestuff, resulting in a green colour. Contemporary books on dyeing describe the procedure thoroughly: first dyeing yellow with leaves of silver birch, dyer’s weed or dyer’s broom, followed by a blue dye-vat of indigo or woad. That method yields the most durable green colour that can be extracted from plant dyes.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 123, 340, 370 & 373).

- Kjellberg, Sven T., Ull och Ylle, Lund 1943 (pp. 373-375, 414 & 461).

- Linder [Lindestolpe], Johan, Swenska färgekonst, 1720.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Folkdräkter, Stockholm 1971 (Quote in translation from Swedish: p. 46).

- Osbeck, Pehr, Utkast til beskrifning öfver Laholms Prosteri 1796, Lund (facsimile) 1922.

- The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm, Sweden; Fabric & Wool Sample Book 1751 (research visit in 2014).

- Warg, Kajsa, Beskrifning på swenska färgegräsen, huru de af allmogen och andra här i riket warda nyttjade til färgning, Stockholm 1765.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE