ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

BOATSWAINS AND SAILS

– Working with Linen and Hemp Sails on Whitby ships: 1740s to 1820s

Muster rolls recorded – among other occupations – those responsible for sails and rigging on ships; these men were usually known by the name of ‘boatswain’ or less often ‘bosun’; the spelling varies. Whitby Museum Library and Archive have a unique collection of such local records, ranging from 1747 to 1795 and supplemented by sporadic years between 1800 and 1850. This information also comes from the pension regulations of Whitby Merchant Seamen’s Hospital. Every sailor working on a merchant ship was expected to pay sixpence a month for insurance against injury or death, with the prospective beneficiaries his widow and children (if any). The material is highly comprehensive, and my studies include a selection from 1749 and 1791. This essay will also give examples from William Scoresby the Younger’s journals and notebooks, which registered notations linked to the boatswain or sailmaker on his ship during long Arctic voyages in the early 19th century.

-800x450.jpg) ‘A Muster roll of Prince William of Whitby’ listing a crew of 34 men, including the London-born boatswain John Blackly, paid from 8th May 1751 until 1st Dec., when the ship was finally laid up. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Muster roll 1751). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

‘A Muster roll of Prince William of Whitby’ listing a crew of 34 men, including the London-born boatswain John Blackly, paid from 8th May 1751 until 1st Dec., when the ship was finally laid up. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Muster roll 1751). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The Muster rolls give information about each ship and its crew, without describing the boatswain’s work or other conditions on board. Even so, they do provide a useful glimpse of this work since by no means every ship carried a boatswain. On large ships, the ‘2nd mate’, ‘3rd mate’ or ‘4th mate’ might be responsible for the sails, while on smaller vessels, this work could be divided among the few seamen on board. Naturally, it was usual to have a boatswain in the crew on the larger merchant ships, in which the work involved in handling sails and rigging, like other jobs, increased with the size of the ship. Ships usually kept the same crew from anything from as little as a month to as long as a whole year, with individuals sometimes engaged for further months or even for several years. On longer voyages, it was usual for a number of people who did the same work to relieve one another when the ship called at particular home ports, and this also applied to boatswains.

-800x405.jpg) ‘A Muster roll of the Silver Ell’ – whose Boatswain Elisha Preston was born in Whitby – ‘Paid the 5 Febr. 1766 to the 16 Dec. laid up’. He worked with a crew of 30 men. As can be seen from this muster roll, the boatswain held a relatively important position on the ship, since here, as in many other muster rolls, he is listed with the carpenter straight after the master and the mate. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Muster roll 1766). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

‘A Muster roll of the Silver Ell’ – whose Boatswain Elisha Preston was born in Whitby – ‘Paid the 5 Febr. 1766 to the 16 Dec. laid up’. He worked with a crew of 30 men. As can be seen from this muster roll, the boatswain held a relatively important position on the ship, since here, as in many other muster rolls, he is listed with the carpenter straight after the master and the mate. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Muster roll 1766). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The notes kept on the various groups of workers engaged on these Whitby ships recorded their places of birth as well as the periods for which they paid their insurance premiums. For example, from 29 Oct. to 4 Dec. 1750, Boatswain John Barrey, born in Whitby, was one of the 58 crew of the European Benj. Tho. Pay, born in London, paid from 2 Nov. 1755 to 26 Feb. the next year [when he served] on board the Stansiker [as one of a crew of] 32 men. Many of the ships that needed a boatswain had a crew of between 20 and 40, but rather smaller ships with 10-15 men could also fall into this category, as can be seen on the Muster roll for the Friends Desire with its crew of 15 men, where Wm. Swan from Whitby paid a premium from 16 Oct. to 30 Nov. 1765. It is also clear that relatively more ships had a boatswain on board during the 1780s and 1790s than earlier. Large ships of the sort that nearly always had one man specially responsible for sails and rigging might now carry a crew averaging 60-70 men or more. On the other hand, one smaller ship from that period that had a boatswain on board was the Thetis of Whitby with Jn. Stephenson from 3rd Dec. 1779 to 4th Aug. 1780. Typical of the late 1780s was David Kirby on board the William & Mary; he worked as a boatswain for 11 months and 22 days, that is to say during the whole of the ship’s voyage. Similarly Joseph Thornhill on the Liberty ship’s boatswain from the beginning of the voyage to its end 7 months and 20 days later as one of a crew averaging 20 men. What all these men had in common was that, among other things, they took over responsibility for the sails after these were delivered by the sailmakers. Either they would be appointed to a newly-built ship with entirely new sails that had to be kept under control in all weathers, or on an older ship, their work would have included the care of older sails that might have needed repairing or altering during the voyage.

-800x592.jpg) This mezzotint etching by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), dated January 1811, gives a visual understanding of the dramatic and treacherous Yorkshire coast near Whitby. The boatswain was one of the important crew members who with all his effort by keeping the sails in as good condition as possible, aimed to hinder such shipwrecking disasters like the one illustrated here. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928, No. 28.97.24).

This mezzotint etching by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), dated January 1811, gives a visual understanding of the dramatic and treacherous Yorkshire coast near Whitby. The boatswain was one of the important crew members who with all his effort by keeping the sails in as good condition as possible, aimed to hinder such shipwrecking disasters like the one illustrated here. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928, No. 28.97.24).Contemporary with Turner’s etching was the voyages by William Scoresby the Younger (1789-1857), who was born and brought up in Whitby as the third child of William (1760-1829) and Mary Scoresby (1765-1819). He sailed to the Arctic on his father’s whaler when only ten years old and continued these voyages every summer until his mid-thirties. His regular journals from 1811 to 1820 principally describe navigation, the weather and the work involved in catching whales during these expeditions, but also include a few passing notes on clothes and daily scores. In his journals for instance, William Scoresby wrote notes, some short and others longer, about the ship’s sails, and his notebooks of 1821 and 1822 also describe sail-making in general. Besides frequent notes on how best to manoeuvre, hoist and lower the ‘Gaf Top Sail’, ‘Fore Sail’, ‘Fore Top Sail’, ‘Mizen’ and ‘Main Sail’, etc., in various weather conditions. During April on the 1813 voyage in a new ship, the Esk, we learn from the journal that there was a sailmaker on board: ‘...Unbent the Main Top Sail and replaced it by a Fore Top Sail in the interim. The Sail Maker immediately set to work to repair it...’

-664x720.jpg) Measurement sketch of sails for the Sailmaker, in Scoresby’s Baffin notebook 1822. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Scoresby Collection, SCO595). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Measurement sketch of sails for the Sailmaker, in Scoresby’s Baffin notebook 1822. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Scoresby Collection, SCO595). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

That a sail-maker or boatswain could really be necessary on board in the strong prevailing winds on these Arctic expeditions is made clear again in an entry on 4th May 1816: ‘During this day both fore & main top-sail broke.’ Similarly, a list of the crew at the beginning of the 1817 voyage records on 15 March that there was a ‘Second mate, skeeman, or boatswain’ on board. Scoresby’s notebooks for 1821 and 1822 both reinforce this statement, since each year those on board included a ‘Sailmaker’ who needed to bring with him ‘Canvas, Tarpaulin, Whipping, Sewing thread’ in various quantities for the trip.

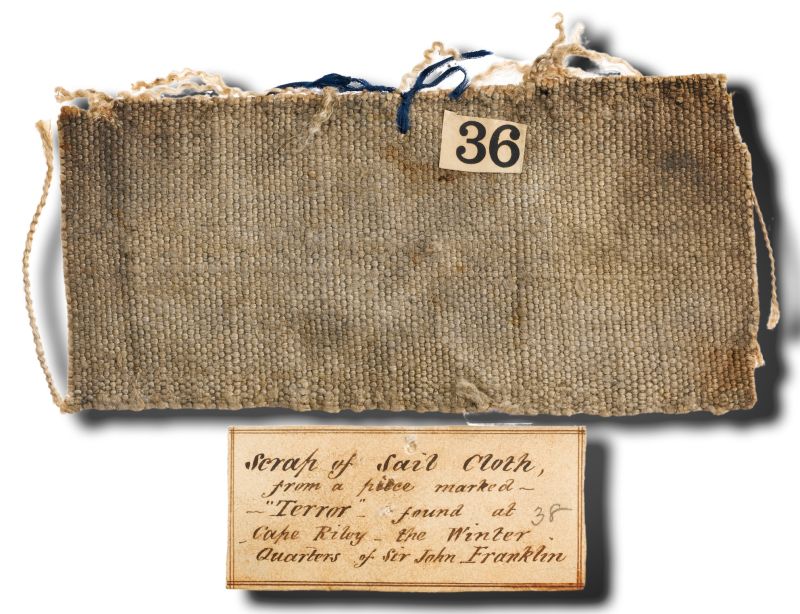

It has proved hard to find large or even small fragments of the cloth used in the sails of Whitby ships or sailcloth shipped elsewhere. However, Whitby is not unique since torn or worn-out sailcloths were used as rag scrap and for making high-quality paper up to the late 19th century. This is why so few early sails can be studied since even the smallest fragments were likely to be recycled. This rare tiny scrap (from the ship ‘Terror’ built in 1813) is one example of ordinary plain woven sailcloth, a type of cloth which had looked very similar long before this date. (Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, United Kingdom. F6668-001).

It has proved hard to find large or even small fragments of the cloth used in the sails of Whitby ships or sailcloth shipped elsewhere. However, Whitby is not unique since torn or worn-out sailcloths were used as rag scrap and for making high-quality paper up to the late 19th century. This is why so few early sails can be studied since even the smallest fragments were likely to be recycled. This rare tiny scrap (from the ship ‘Terror’ built in 1813) is one example of ordinary plain woven sailcloth, a type of cloth which had looked very similar long before this date. (Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, United Kingdom. F6668-001). Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors’, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 173-178).

- Jackson, C. Ian, ed. The Arctic Whaling Journals of William Scoresby the Younger, Vol. I, The voyages of 1811, 1812 and 1813 | Vol. II, The voyages of 1814, 1815 and 1816 | Vol. III, The voyages of 1817, 1818 and 1820. London 2003-2009.

- Whitby Museum (Whitby Lit. & Phil.), Whitby, United Kingdom. Library and Archive: | Muster rolls; 1749-1751, 1756-1757, 1765-1767, 1780-1782 & 1789-1791. | Scoresby Collection; Scoresby’s Notebook for the Baffin, 1821. & Scoresby’s Notebook for the Baffin, 1822. | (Researched in 2008-2009).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE