ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

BROWN COLOURS

– Carl Linnaeus’ Provincial Tours and Dyeing Experiments

Producing a genuine brown colour with natural dyes was considerably more complex than achieving a yellow hue; various types of moss, lichen and bark were commonly used. Some herbs can also yield brownish colours with varying results, but most frequently tending towards yellow. Even so, the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) made notes in his travel journals of brown dyes for cloth and yarn during several of his Swedish provincial tours in the 1730s-40s. This essay will look closer into these obstacles and possibilities – from an 18th century perspective and via my own dye experiments over many years – to achieve colourfast and beautiful brown shades. Additional research of dye manuals, Linnaeus’ floras and household books, a piece of sandalwood from East India and other primary sources aim to enlighten further traditions related to dyeing brown colours.

In this oil on canvas by Alexander Roslin (1775), Carl Linnaeus is portrayed in brown-red garments reasonably late in his life. He is dressed in a ruffled shirt and probably ‘a frock coat of mixed colours with gilded buttons’, listed under ‘Everyday Clothes’ in the estate inventory three years later. However, judging by portraits, there is no indication that Linnaeus preferred brown shades for his clothes. Besides, brown-red garments give examples of depicted red, blue and black clothes over his lifetime. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).

In this oil on canvas by Alexander Roslin (1775), Carl Linnaeus is portrayed in brown-red garments reasonably late in his life. He is dressed in a ruffled shirt and probably ‘a frock coat of mixed colours with gilded buttons’, listed under ‘Everyday Clothes’ in the estate inventory three years later. However, judging by portraits, there is no indication that Linnaeus preferred brown shades for his clothes. Besides, brown-red garments give examples of depicted red, blue and black clothes over his lifetime. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).Carl Linnaeus and his contemporaries were eager to investigate the excellent qualities of domestically grown plants for dyeing, which was part of the aim for the best development potential for the country’s mercantile economy. At the time, this was seen to have the potential to improve conditions for the country as well as for its inhabitants. However, this did not exclude the existence of imported alternatives for dyeing. Among a multitude of observations related to textile dyeing, he studied a few plants from which the dyers could obtain brown shades during his final provincial journey in 1749. On 25 June this year, he noted in the Skåne journal: ‘Bur-marigold was collected when she was ripe and yellow in order therewith to dye yellow-brown’. On the visit to the village Everlöv on 3 July, the plants made use of in the area for dyeing brown were furthermore listed: ‘birch bark, bur-marigold, wild marjoram and the berries of common buckthorn which tended towards russet’. Considering that rocket moss was uncommon in all but the most northerly part of Skåne, the dyeing of brown was much restricted in the province. On his journey home from Skåne, at Stenbrohult in Småland on 2 August, Linnaeus found by contrast that suitable lichens grew in abundance. He wrote: ‘Lichen tinctorius FL. 946 along with Lichen saxeus Fl. 947 grew everywhere on the stones ... Both of them have on the upper side hollowed-out humps, the former of the two being preeminent. They both dye brown, but the latter does so more faintly.’

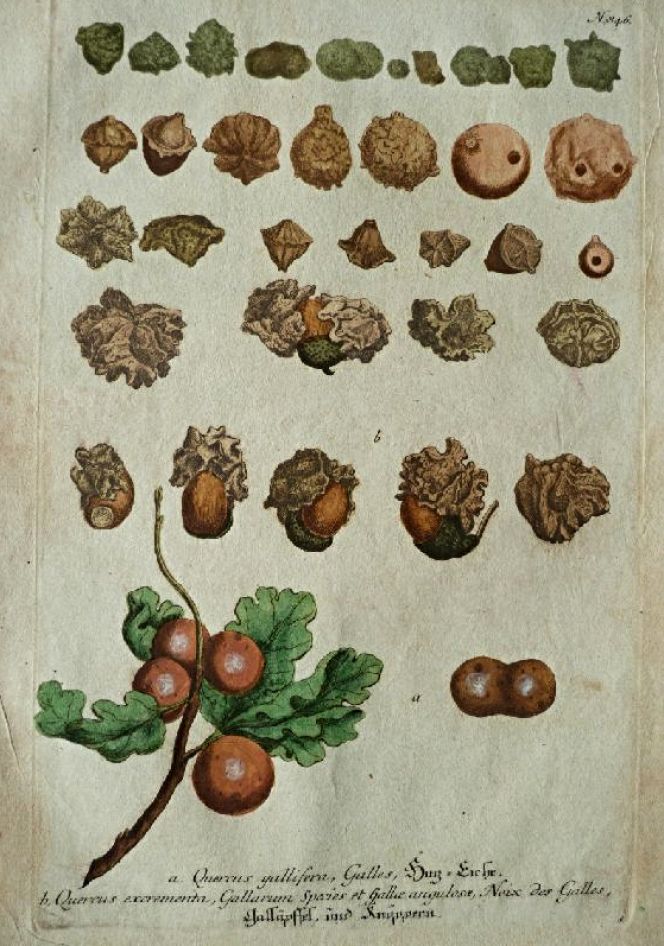

Gall or oak apples are little round or uneven growths which can appear on the leaves of Swedish oak trees and on Quercus species of other countries. Large quantities were nevertheless imported into Sweden in the 18th century, mainly from Asia, to cover the demand from the dye-works as well as other operations. (From: Weinmann…Plate – N. 846, vol. IV. 1745).

Gall or oak apples are little round or uneven growths which can appear on the leaves of Swedish oak trees and on Quercus species of other countries. Large quantities were nevertheless imported into Sweden in the 18th century, mainly from Asia, to cover the demand from the dye-works as well as other operations. (From: Weinmann…Plate – N. 846, vol. IV. 1745).Linnaeus’ Öland and Gotland journey in 1741 passed through the woodlands of Småland province, where similar conditions prevailed. Stenmossa (rock lichen), a dye-lichen growing on stones, was mentioned in many places in that region. In days gone by the term moss was also frequently used for what is today called lichen, and what is more, the names of plants were in some cases changed. That is why dye-lichen, for example, was described on 27 May 1741 (Parmelia saxatilis) as stenmossa, a lichen of an ash-grey to brown-grey colour which grows on stones. From a village in Småland, it was recorded how the dyeing could be done. ‘Brown is dyed with rock lichen, which is boiled in water, then the moss is strained off before the yarn is added, otherwise, it becomes blotchy from the moss.’ Linnaeus also noticed on the same occasion how brown could be obtained, ‘Soot, boiled with small beer also gives a brown colour, but lighter than from rock lichen’. The soot colour did not however have the same durable properties as the rock lichen, but a common factor for both methods was nonetheless that the dye fixed to the yarn without being mordanted with alum. On Öland the women dyed with rock lichen in a similar fashion, the difference being that they added lye to the water ‘so that the dye might fix better, but the yarn is not steeped in a mordant bath’ (9 June). He also pointed out that brown was locally dyed with wild marjoram and that the result was similar to the sought-after ‘rock-lichen-colour’. Dyeing with bark has to be planned well in advance for the best outcome, as it needs to be left to dry for a year. The traditions of the people of Öland concur perfectly with that fact, as they used to dye brown using dried bark from buckthorn, while the people of Gotland dyed in the same way with “yellow bark” – bark from alder buckthorn.

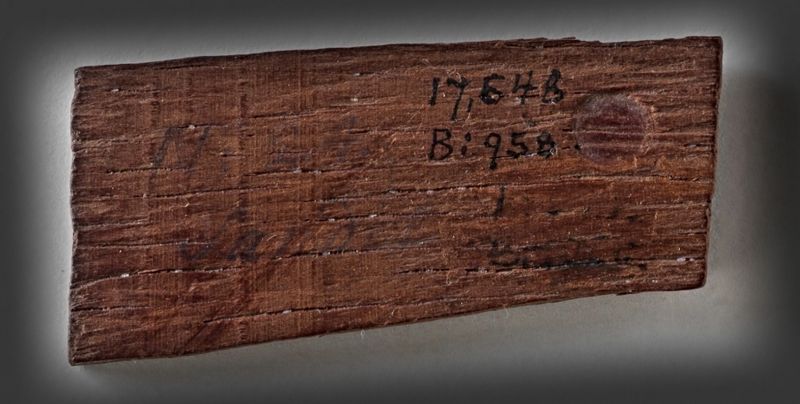

A piece of sandal-wood, contemporary with Carl Linnaeus’ observations. The sample probably originates from imported commodities to Sweden via the Swedish East India Company in the mid-18th century. | This piece of wood was part of economics professor Anders Bergh’s (1711-1774) educational collection in the period from the 1740s up to his death in 1774. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:958. DigitaltMuseum).

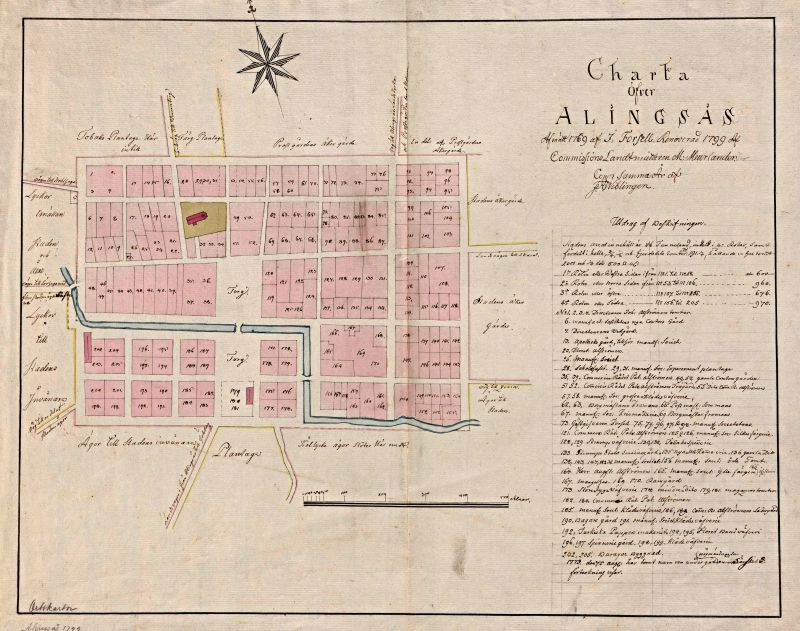

A piece of sandal-wood, contemporary with Carl Linnaeus’ observations. The sample probably originates from imported commodities to Sweden via the Swedish East India Company in the mid-18th century. | This piece of wood was part of economics professor Anders Bergh’s (1711-1774) educational collection in the period from the 1740s up to his death in 1774. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:958. DigitaltMuseum). Map of Alingsås, by J. Forsell in 1769 and renovated in 1799 by M. Meurlander. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Lund. Alvin-record: 97728. Public Domain).

Map of Alingsås, by J. Forsell in 1769 and renovated in 1799 by M. Meurlander. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Lund. Alvin-record: 97728. Public Domain).From Linnaeus’s tour of Västergötland in 1746, there were no notes on the subject, but a closer study of Jonas Alström’s [ennobled Alströmer] (1685-1761) store at the textile mill in Alingsås of imported dyes makes it clear that dyeing of brown could have been done there. In the storehouse was to be found on 7 July ‘sandal-wood, madder, yellow-wood and oak-apple’ which together gave a brown colour. However, with time, the colour probably changed to a more red shade, bearing in mind sandalwood's relatively poor light resistance. The above somewhat later dated fact-filled map of Alingsås town – at a time when his son Patrick Alströmer (1733-1804) led the manufacturing business – interestingly marked out the area for ‘Färg Plantage’ (Dye Plantation) in the left upper part of the map. Madder was one of the dye plants (mentioned by Linnaeus at his visit), whilst ‘125 & 126’ was a ‘Silk dye workshop’ adjoined to Patrick Alströmer’s property number ‘121’.

Sandal-wood was an imported tropical dye-wood, as mentioned earlier, like yellow-wood, roots of common madder and oak-apple, was chipped or ground to a powder. Alder is another significant type of wood that was used, its bark being described in Linnaeus’ Flora Oeconomica as follows: ‘mixed with filings [it] gives a brown-red colour, with which fishermen in Norrland dye their nets’.

On the homeward journey from Linnaeus’ very first journey to Lapland through Finland, he also visited the Åland Islands, where on 6 October 1732 women’s methods of dyeing with dye-lichen were seen and recorded, ‘...the moss is boiled with water and wadmal or stockings only, with no alum, some add a little orchil’. That note reveals that even islanders were able to dye using imported stuff of tropical nature. The seed cases of that plant contain a red and yellow dyestuff, which was ground and made into cakes. It is likely that the orchil dye contributed to making the colour of the Åland women’s brown fabrics and stockings more distinctive.

A selection of nuances can be achieved with the help of bark, lichen and leaves in southern Sweden. After experiments with the dyeing of browns, it can also be confirmed that it is not only difficult to produce a “genuine brown” colour but also that the time allowed for the bark to dry and the amount of material used produce significant variations in the nuances of brown-yellow. Truly brown colour has only been achieved in my dyeing trials by using grey rock lichen, also referred to as ‘stenmossa’ by Linnaeus. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

A selection of nuances can be achieved with the help of bark, lichen and leaves in southern Sweden. After experiments with the dyeing of browns, it can also be confirmed that it is not only difficult to produce a “genuine brown” colour but also that the time allowed for the bark to dry and the amount of material used produce significant variations in the nuances of brown-yellow. Truly brown colour has only been achieved in my dyeing trials by using grey rock lichen, also referred to as ‘stenmossa’ by Linnaeus. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation. Bearing in mind that potassium dichromate was not available in the 18th century, dyeing brown domestically had its limitations. That type of toxic mordanting can otherwise turn several plants into brown hues, such as leaves of common alder (Alnus glutinosa) and silver birch (Betula alba), the flowers of heather (Calluna vulgaris) or cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris), all of which produce yellow colours, provided the yarn has been mordanted with alum. Cinder lichen (Aspicilia cinerea), also referred to as rock lichen by Linnaeus, was the most crucial source for dyeing brown, as described during the provincial tours. What is so special about that lichen is that it yields a strongly brown-red colour to woollen yarn without the need for mordanting baths. During my experiments with dyeing brown, his note from Småland was followed: that the lichen was best boiled in the water, which was then strained off before the yarn was added to prevent the yarn from becoming blotchy. The dyeing continued for three hours at 90°C, and the yarn then became the expected even brown-red or russet colour.

Dyeing with domestic plants was not without its problems in Linnaeus’ day, which can be seen in his many notes and comments on the subject – for all colours of the spectrum. Trying to reconstruct plant dyeing today according to the principles of that time can cause different problems, too. (Sweden has a unique public right of access, so-called allemansrätt, inscribed in the country’s constitution, which with some exceptions, allows for picking herbs, leaves, lichen and bark). First, the dyer must ensure that plants are gathered with great care; plants that flourished in profusion in the 18th century may be rare today and, therefore protected. And it is not permitted to de-bark trees other than if one has access to a forest or garden of one’s own. Environmental impact, however, is chiefly evident in the presence of lichens, which were much more abundant before the emergence of industrialisation. The natural landscape was also much vaster when Linnaeus was alive, as considerably fewer people with utterly restricted mobility lived together in the same space as today’s intensely mobile population.

Sources:

- Billing, Ebba, Växtfärgning för skånsk konstvävnad, Lund 1913 (facts about sandalwood).

- Hansen, Viveka (Experiments in textile dyeing of brown colours on woollen yarn).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 359-61 & 426. | See more: dye plants, related to brown colours, Appendix I. pp. 429-35).

- Hazelius-Berg, Gunnel & Wallin, Sigurd, ‘Linnés kläder i samlingen på Hammarby’ Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1956-57, pp. 57-84.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Svensk Flora – Flora Svecica, Stockholm 1755.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Flora Oeconomica (1737), Uppsala, facsimile 1971 (alder bark no. 775. B).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan (1732). Published after the manuscript by Algot Hellbom, Sigurd Fries and Roger Jacobsson, Umeå 2003.

- Sandberg, Gösta, & Sisefsky, Jan, Växtfärgning, Stockholm 1979.

- Weinmann, Johann Wilhelm, Phytanthoza Iconographia, Ratisbonæ [Regensburg] 1735- 1745.

- Westring, Joh. P. Svenska lafvarnas Färghistoria eller sättet att använda dem till färgning och annan hushållsnytta, Stockholm 1805.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE