ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

CARSTEN NIEBUHR’S TEXTILE OBSERVATIONS

– A Journey from Syria to Denmark: 1766-1767

Trade with English, French and Venetian broadcloths were some of many detailed observations by the sole survivor Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) – of the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia – during his last two years of travelling by land and sea. This third and final essay will also take a closer look at his thoughts on warm and practical clothes on horseback, seen from a European and Turkish/Syrian perspective. A few contemporary portraits, a map and preserved woollen cloths add further comparisons to Niebuhr’s notes – which was introduced with the title ‘Travel through Syria and Palestine to Cyprus and through Asia Minor and Turkey to Germany and Copenhagen’. However, his travel journal ends at the border between Poland and Germany; due to that, the remaining area was seen as so well known to his readers of the time.

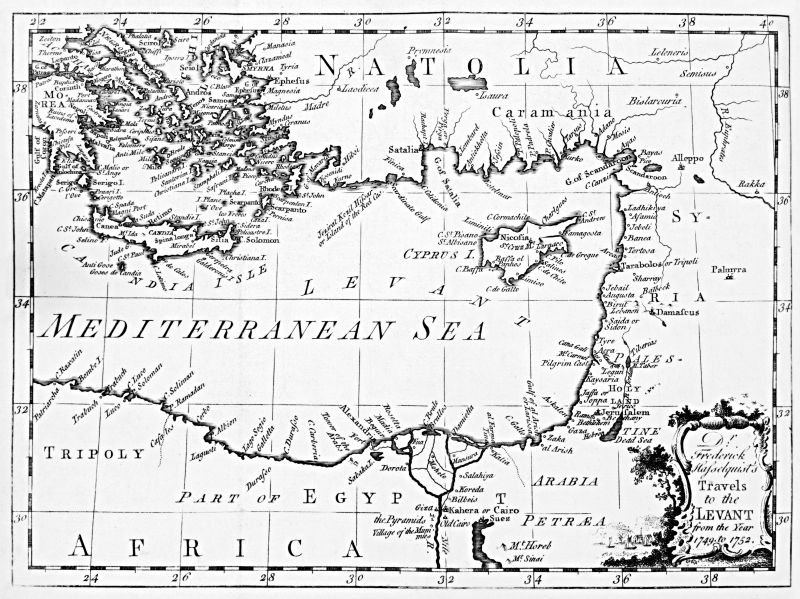

Mid-18th century map centred around places visited by the cartographer Carsten Niebuhr during his travel in 1766 – Jaffa, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Damascus, Cyprus etc. This particular map was included in the Swedish naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist’s travel journal, when he visited the same geographical area some years earlier, 1749 to 1752 (From: Hasselquist, F., Voyages and Travels in the Levant. In the years 1749, 50, 51, 52, London 1766).

Mid-18th century map centred around places visited by the cartographer Carsten Niebuhr during his travel in 1766 – Jaffa, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Damascus, Cyprus etc. This particular map was included in the Swedish naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist’s travel journal, when he visited the same geographical area some years earlier, 1749 to 1752 (From: Hasselquist, F., Voyages and Travels in the Levant. In the years 1749, 50, 51, 52, London 1766). During his time in Aleppo, Carsten Niebuhr made an observation of the extensive, lucrative as well as complex trade in broadcloth, which must have been based on knowledge learned from his close contacts with various local groups of individuals, judging by the notes in his travel journal of June 1766.

- 'Frenchmen, Englishmen, Dutchmen and Venetians have consulates in Aleppo who are highly regarded. Broadcloth is the most important item that Europeans supply to the Orient. The French make their cloths thin and light, but understand to give the same a beautiful look; Their manufacturing are located in the provinces where it is cheap to produce, the cargo from Marseille to the Levant is not as expensive as from northern Europe, so they can sell their broadcloth cheaper than other nations, which gives them a very good market. The distinguished Turks who annually purchase new clothes for their servants to the Bayram celebration use French broadcloth. The gentlemen themselves dress in English broadcloth, and for travel clothing, they use a fine, very thick red Venetian broadcloth. Due to the much higher price of this broadcloth, the English have far less market potential compared to the French, and there is even less demand for the Venetian broadcloth. Because of the barbaric piracy, at Venice they must carry out the goods on armed ships, making their trade much more difficult and the transport expensive.’

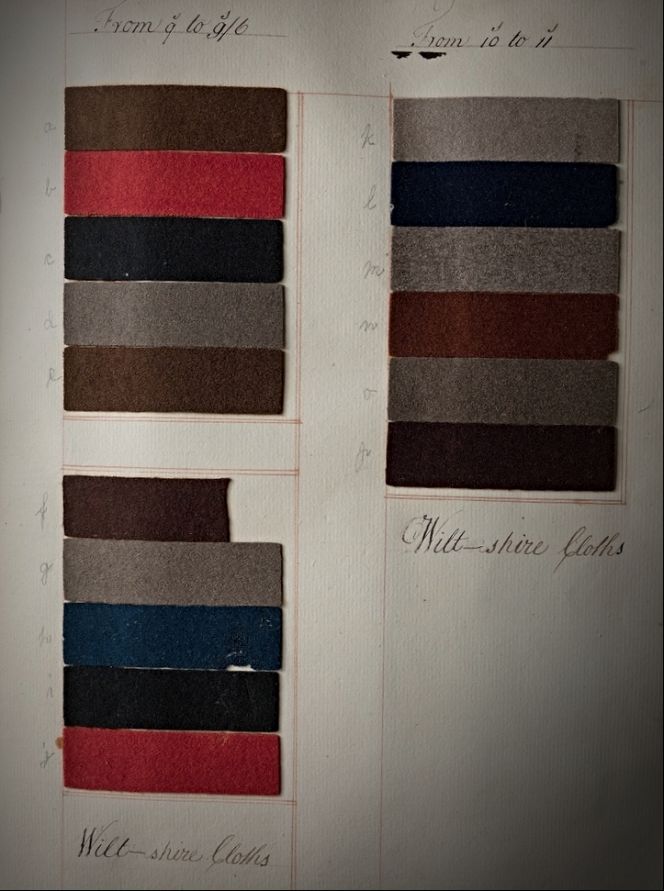

These samples of ‘Wilt-shire Cloths’ are good contemporary comparisons of the high quality English broadcloth, which were widely traded during the 18th century. Among other places in Aleppo as mentioned by Niebuhr in his travel journal in June 1766. This particular page of samples is part of the Swedish professor Anders Berch’s Collection, dated to around the 1740s to 1770s. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm Sweden. Anders Berch Collection, no 17648b:2. Digitalt Museum).

These samples of ‘Wilt-shire Cloths’ are good contemporary comparisons of the high quality English broadcloth, which were widely traded during the 18th century. Among other places in Aleppo as mentioned by Niebuhr in his travel journal in June 1766. This particular page of samples is part of the Swedish professor Anders Berch’s Collection, dated to around the 1740s to 1770s. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm Sweden. Anders Berch Collection, no 17648b:2. Digitalt Museum).Furthermore, Niebuhr made an additional note about some changing circumstances, which may have an effect on the all-important trade in cloth: ‘Since my return from the Orient, Venice has ended peace with the free states on the African coast, but the latter has broken the peace on various occasions. The French will undoubtedly make the Venetian trade on the Mediterranean Sea and the Levant difficult.’

In the following month – July 1766 – Niebuhr made two enlightening observations connected to textile trade. First from Cyprus: ‘The most important produce for the island of Cyprus are: wine, silk, cotton, wool, wheat and barley. Just like the number of inhabitants gradually have ceased, the export of these products have become less and less.’ Followed by notes from a more southerly situated place – Jaffa in Palestine: ‘The trade of soap, cotton and potash, which the present Europeans use in soap and glass factories, are still significant, and there are some French merchants, partly because of these products, and even more due to sell their broadcloth.’

The journey then continued in a northerly direction and in September 1766, Homs in Syria had been reached, where he just briefly mentioned: ’In Homs much silk is produced, and you can also find good workshops here’. To travel with a caravan was overall seen as the safest alternative, which Niebuhr preferred during long stretches of the journey and even for shorter excursions, if he did not sail by boat.

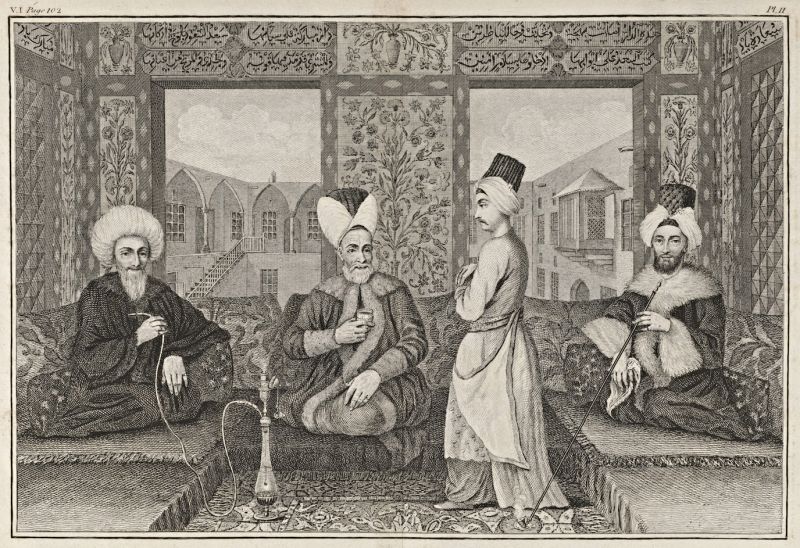

A late 18th century illustration of inhabitants from Aleppo, seated in a wealthy interior. This informative depiction gives a detailed view of the men’s warm wide-cut clothing, fur edgings etc – comparable in more than one way with Niebuhr’s travel notes, quoted below. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London. Published in. G. G. and J. Robinson, London 1794. No: EPB 45188/C Vol. 1).

A late 18th century illustration of inhabitants from Aleppo, seated in a wealthy interior. This informative depiction gives a detailed view of the men’s warm wide-cut clothing, fur edgings etc – comparable in more than one way with Niebuhr’s travel notes, quoted below. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London. Published in. G. G. and J. Robinson, London 1794. No: EPB 45188/C Vol. 1).During the journey from Aleppo to Konya in December 1766, Niebuhr included a description in his journal of practical and unpractical clothing during long cold winter travel on horseback, which in this context not only revealed particular usefulness of various textile materials but also long-lived traditions.

- ‘I had lived so long in hot countries that it seems unusual to me again to come to a region where winter is as severe as in Germany. The cold I felt here troubled me a lot. But the Turks understand on their trips on horseback better to protect themselves from cold and violent weather than we Europeans, and I have taken good winter clothes from Aleppo. My underclothes were made of broadcloth, which I wore under the big and wide trousers. I had a nice fur and over it a travel coat of strong Venetian canvas. A large jacket of the same fabric covered my head (on which I carried an Armenian hat), neck and shoulders, and whenever I wanted, also the side of my face from which direction the wind blew. The lapels on the sleeves, which usually is folded back, I covered over my hands, which was further covered with gloves. In Europe, where you wear socks in tight boots, travelling, especially on horseback, it is always difficult to keep your feet warm, because when the socks have been wet they do not warm much. Here, you wind a long woollen cloth around your feet, which you wring and dry by the fire, and it keeps your feet very warm in the wide boots. Thus dressed like this, you look extremely plump, but so I have travelled many miles in Anatolia in strong frost and snowstorms, where I in Europe and dressed in European clothes would hardly have gone out on horseback.’

![From his travel notes, Niebuhr included several plates with detailed drawings of traditional headgear from Constantinople [Istanbul], the Turkish countryside, Egypt and other places. Some of these originated from the area he passed through and visited during his last year of travel. Of particular interest: Fig. 21 which shows a style of turban used by some men in Turkish villages. Fig. 22 was used by learned men in Constantinople, such a model was stuffed with cotton to get the correct shape according to Niebuhr’s notes. Whilst, Fig. 24 was worn by the ‘distinguished clergy throughout Turkey’. (From: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XXI).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4-constantinople-d-664x922.jpg) From his travel notes, Niebuhr included several plates with detailed drawings of traditional headgear from Constantinople [Istanbul], the Turkish countryside, Egypt and other places. Some of these originated from the area he passed through and visited during his last year of travel. Of particular interest: Fig. 21 which shows a style of turban used by some men in Turkish villages. Fig. 22 was used by learned men in Constantinople, such a model was stuffed with cotton to get the correct shape according to Niebuhr’s notes. Whilst, Fig. 24 was worn by the ‘distinguished clergy throughout Turkey’. (From: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XXI).

From his travel notes, Niebuhr included several plates with detailed drawings of traditional headgear from Constantinople [Istanbul], the Turkish countryside, Egypt and other places. Some of these originated from the area he passed through and visited during his last year of travel. Of particular interest: Fig. 21 which shows a style of turban used by some men in Turkish villages. Fig. 22 was used by learned men in Constantinople, such a model was stuffed with cotton to get the correct shape according to Niebuhr’s notes. Whilst, Fig. 24 was worn by the ‘distinguished clergy throughout Turkey’. (From: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XXI).In Constantinople and further on through the Balkans and Poland, Niebuhr, on several occasions, mentioned how he stayed safe or felt comfortable by wearing locally accepted clothes or European-style dress. Additionally, he made some comments on farming families’ clothing, the traditions of Christians and Jews versus Muslims – just like at many earlier visited places. This is however, a subject which inflicts great complexity seen from the perspective of religion as well as geographical boundaries, trade and historical events – and has only been looked at briefly throughout this three-part series about Carsten Niebuhr’s textile observations from a multitude of angels over widespread areas in Europe, Africa and Asia during the 1760s.

Portrait of Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) dressed in a warm woollen broadcloth coat and a shirt with a lace frill down the front, probably copied after an 18th century portrait in 1908 by the artist Walther Witting (1864-1940). In concluding words, Niebuhr lived up to an old age so besides having time to publish his extensive journals and observations from the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia – lasting from 1761 to 1767 – he also made it possible for some of the other participants’ journals and floras to be saved/posthumously published. Furthermore Niebuhr held a position within the civil service of Danish Holstein area and got several recognitions of honour for his work related to the Expedition in the 1760s. (Courtesy: Dithmarscher Landesmuseum, Wikimedia Commons).

Portrait of Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) dressed in a warm woollen broadcloth coat and a shirt with a lace frill down the front, probably copied after an 18th century portrait in 1908 by the artist Walther Witting (1864-1940). In concluding words, Niebuhr lived up to an old age so besides having time to publish his extensive journals and observations from the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia – lasting from 1761 to 1767 – he also made it possible for some of the other participants’ journals and floras to be saved/posthumously published. Furthermore Niebuhr held a position within the civil service of Danish Holstein area and got several recognitions of honour for his work related to the Expedition in the 1760s. (Courtesy: Dithmarscher Landesmuseum, Wikimedia Commons).Notice: Quotes have been translated for this essay by Viveka Hansen – from Danish to English from (Niebuhr…2003), if not otherwise stated. This is the third and final essay about Carsten Niebuhr’s textile observations from 1761 to 1767.

Sources:

- Baack, L.J., Undying Curiosity – Carsten Niebuhr and The Royal Expedition to Arabia (1761-1767), Stuttgart 2014.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Hasselquist, Frederick, Voyages and Travels in the Levant. In the years 1749, 50, 51, 52, London 1766.

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. Vol. One & Two. Copenhagen, 1774-1778.

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Rejsebeskrivelse fra Arabien og andre omkringliggende lande (Intr., Michael Harbsmeier), København 2003. (Vol. One: p. 188 & Vol. Two: pp. 451-636).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE