ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

CARSTEN NIEBUHR’S TEXTILE OBSERVATIONS

– A Journey from Denmark to India: 1761-1764

Cotton, natural dyes, linen and textile trade from India, Yemen, Syria, Cyprus and other areas along the route were observed by the cartographer Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815) in his travel journal and historical descriptions from 1761 to 1767. After somewhat more than two years of travel, however, the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia sadly lost five of its six members due to illnesses over several months in the year 1763. This series of three essays will give some background information about the participants, but foremost emphasises the textile perspectives during the continuous part of the expedition, which lasted from July 1763 and up to the time when Niebuhr returned to Denmark in November 1767.

-664x870.jpg) In his journal Carsten Niebuhr wrote the following in connection with this portrait: ‘The costume I received from the imam was made in the same fashion like those worn by the high-born Arabs in Yemen. The way they dress is depicted in Plate LXXI…’ on 26 July, 1763. That the portrait is of Niebuhr himself is confirmed by information in his book ‘Rejsebeskrivelse fra Arabien’, which stated that the clothes in which he was portrayed had been presented to him as a gift during his visit to the country shortly after the naturalist Peter Forsskål’s death, about a month before the participants of the expedition sailed towards India. (From: Niebuhr…1774. Tab. LXXI).

In his journal Carsten Niebuhr wrote the following in connection with this portrait: ‘The costume I received from the imam was made in the same fashion like those worn by the high-born Arabs in Yemen. The way they dress is depicted in Plate LXXI…’ on 26 July, 1763. That the portrait is of Niebuhr himself is confirmed by information in his book ‘Rejsebeskrivelse fra Arabien’, which stated that the clothes in which he was portrayed had been presented to him as a gift during his visit to the country shortly after the naturalist Peter Forsskål’s death, about a month before the participants of the expedition sailed towards India. (From: Niebuhr…1774. Tab. LXXI).In the autumn of 1760, all six participants were assembled in København (Copenhagen) to determine their plans for Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia), which they began on 7 January 1761. The journey became troubled from the start with gales alternating with flat calm; the crew succumbing to the cold and the ship being forced to return to Helsingør three times, due to weather as well as to replenish the crew. It was only on the fourth attempt at leaving Helsingør that the group managed to get away on 12 March, arriving in the Mediterranean in the month of May. Visits were paid to Malta and Istanbul, amongst other places, before the journey continued to Egypt, one of the main destinations where the expedition carried out various work lasting a year. In October 1762, the journey continued to South Arabia where the botanical fieldwork became considerable, often assisted by local inhabitants. But everything was not going to plan. The philologist Fredrik Christian von Haven (1728-1763) died in May 1763 and a while later the naturalist Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) fell ill at the end of June, also suffering from malaria, he died in Yemen on 11 July the same year. After Forsskål’s demise, the malaria-stricken group of travelling naturalists had to suffer further deaths and hardships.

![Niebuhr’s ethnographic “curiosities” which he brought back included these three striped silk (or linen) qualities from Yemen – woven in plain weave and lozenge twill borders with fringes – which would have been used for the country’s local clothing. The predominant sections of these long pieces of fabric, 365-380 cm in length, had been indigo-dyed in a number of nuances. While a forth textile was of Turkish origin with a symmetrical embroidery on white linen, 165 cm in length. These four pieces are rare survivors and most probably made in the 1760s, but judging by a museum note in 1807, Niebuhr’s collection initially included at least ‘five different Arabic garments…’. (Courtesy: National Museum of Denmark. No. EFc11-13. Quote: Dam-Mikkelsen…p. 95. [see sources]).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-800x539.jpg) Niebuhr’s ethnographic “curiosities” which he brought back included these three striped silk (or linen) qualities from Yemen – woven in plain weave and lozenge twill borders with fringes – which would have been used for the country’s local clothing. The predominant sections of these long pieces of fabric, 365-380 cm in length, had been indigo-dyed in a number of nuances. While a forth textile was of Turkish origin with a symmetrical embroidery on white linen, 165 cm in length. These four pieces are rare survivors and most probably made in the 1760s, but judging by a museum note in 1807, Niebuhr’s collection initially included at least ‘five different Arabic garments…’. (Courtesy: National Museum of Denmark. No. EFc11-13. Quote: Dam-Mikkelsen…p. 95. [see sources]).

Niebuhr’s ethnographic “curiosities” which he brought back included these three striped silk (or linen) qualities from Yemen – woven in plain weave and lozenge twill borders with fringes – which would have been used for the country’s local clothing. The predominant sections of these long pieces of fabric, 365-380 cm in length, had been indigo-dyed in a number of nuances. While a forth textile was of Turkish origin with a symmetrical embroidery on white linen, 165 cm in length. These four pieces are rare survivors and most probably made in the 1760s, but judging by a museum note in 1807, Niebuhr’s collection initially included at least ‘five different Arabic garments…’. (Courtesy: National Museum of Denmark. No. EFc11-13. Quote: Dam-Mikkelsen…p. 95. [see sources]).

These unfortunate illnesses progressed during the sea voyage, which started on 23 August 1763, on an English ship from Mocha in Jemen towards Bombay [today Mumbai] in India. Two more of the participants died during the crossing, the artist Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind (1728-1763) on 29 August and the servant Lars Berggren (17??-1763) the day after. Furthermore, the surgeon Christian C. Kramer (1732-1763) died after a few months in Bombay, leaving Carsten Niebuhr alone to carry on with the mission and take care of the extensive collections. Despite all unforeseen hardships, Niebuhr continued to be a careful observer, providing detailed accounts of everyday life, architecture, geography, and more or less everything that caught his eye.

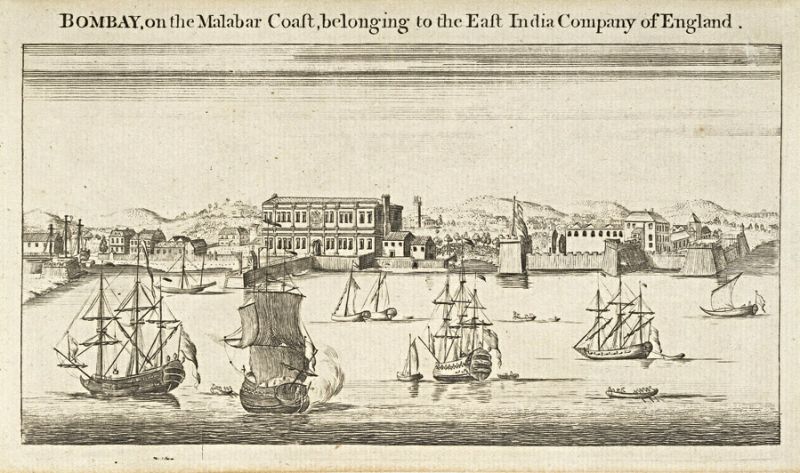

‘Bombay on the Malabar Coast, belonging to the East India Company of England’ dating circa 1754 to 1760, or just a few years prior to Carsten Niebuhr’s stay in Bombay. Line engraving by Jan Van Ryne. (Courtesy: British Library, Online Gallery, Print, P152).

‘Bombay on the Malabar Coast, belonging to the East India Company of England’ dating circa 1754 to 1760, or just a few years prior to Carsten Niebuhr’s stay in Bombay. Line engraving by Jan Van Ryne. (Courtesy: British Library, Online Gallery, Print, P152). The instructions for the expedition also gave some direct advice or orders for the participants, which included instructions on how to address the local inhabitants in visited areas. In the introduction for Carsten Niebuhr’s Beskrivelse af Arabien… (Description of Arabia, 2009), a phenomenon that was not unusual for Europeans at that time is noted: ‘... it is with greatest importance that the members of the expedition avoid showing arrogance toward the local inhabitants, but instead to respect their customs and traditions’. Overall, Niebuhr also seems to have been respectful – seen in the context of the time – in his descriptions and reflections of various peoples, their daily lives, religion, trade, etc, in the vast geographical area he visited.

![Observations of how the Indian merchants dressed in white cotton, was mentioned among other reflections: ‘The sleeves in this dress are very long, but narrow and pushed back over the hand. They have a belt around the hips; their slippers are big and are crooked in the front like our walking shoes or the Finnish Lapps’ [Sami] shoes. In the ears they carry large golden rings, and the rich merchants also like a large-size real pearl in each ear. The shape of their turban, the knife they hold in front of the stomach, in short, the whole inner garment is different from the Arabs, the Turks and the Persians, but also very comfortable in this climate.’ (From: Niebuhr…1778. Tab. XII B).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4(2)-664x843.jpg) Observations of how the Indian merchants dressed in white cotton, was mentioned among other reflections: ‘The sleeves in this dress are very long, but narrow and pushed back over the hand. They have a belt around the hips; their slippers are big and are crooked in the front like our walking shoes or the Finnish Lapps’ [Sami] shoes. In the ears they carry large golden rings, and the rich merchants also like a large-size real pearl in each ear. The shape of their turban, the knife they hold in front of the stomach, in short, the whole inner garment is different from the Arabs, the Turks and the Persians, but also very comfortable in this climate.’ (From: Niebuhr…1778. Tab. XII B).

Observations of how the Indian merchants dressed in white cotton, was mentioned among other reflections: ‘The sleeves in this dress are very long, but narrow and pushed back over the hand. They have a belt around the hips; their slippers are big and are crooked in the front like our walking shoes or the Finnish Lapps’ [Sami] shoes. In the ears they carry large golden rings, and the rich merchants also like a large-size real pearl in each ear. The shape of their turban, the knife they hold in front of the stomach, in short, the whole inner garment is different from the Arabs, the Turks and the Persians, but also very comfortable in this climate.’ (From: Niebuhr…1778. Tab. XII B).In notes about Bombay and Surat in late 1763 and early 1764, Niebuhr gave detailed accounts about the trade. A few sections have been quoted in a translation for this essay, to give an idea of the complex crisscrossing of goods between various harbours, including textile goods as cottons and the desirable cochineal for dyeing yarn and cloth red:

- ’All ships from the East India Company which come from Europe, sail to one of the four main offices…The most dominating goods the English bring to Bombay is canvas [linen or cotton], and most of it is sold on to Persia and Basra. Other wares they bring to here are cochineal, ivory, and iron. A large amount of European wares are sold at open auctions. Goods sent from Bombay to England are first and foremost pepper from the Malabar coast, saltpetre from Scindi and all sorts of canvas [cottons] from Surat. Of the canvas, a lot is re-exported from London to Guinea.’

Niebuhr sailed from Bombay on 24 March in 1764 and reached the harbour road of Surat two days later. During the coming days, he added some notes about trading circumstances in Surat between various groups of people, which included the Mughal Empire, several European countries and their so-called Factories (trading and storage houses), that is to say, the English, Dutch, French and Portuguese. Additionally, the Swedish East India Company traded in Surat to a minor extent, together with neighbouring areas that liked to take part in the wide-ranging trade of this port. By walking the streets of Surat, Niebuhr also made detailed descriptions of the various inhabitants' clothes and how it was possible to travel in a comfortable palanquin if one preferred. This equipage was mostly draped with curtains, to protect from the sun, whilst an illustration from the original edition (Tab. XII) also depicted an oblong round cushion for further comfort.

Carsten Niebuhr emphasised the favourable position of Surat too in March 1764: ‘Surat is the most important port in the whole of the Mughal Empire and therefore the trade in this city is very substantial. The merchants living here, send ships to the Persian and Arab Gulf, to the African coast and to the Malabar and Coromandel coasts, even to China; and the many precious manufactures produced in the various provinces and cities of the Mughal Empire, they get to the country with large caravans…’ One of the most important goods were fine cottons in a wide range of qualities. Indian textiles was not part of Niebuhr’s collection though, but the depicted example is a well-preserved contemporary comparison – a fabric sample which was included in the Swedish professor Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) collection. This sample and a number of other cottons within the collection are regarded as of Indian origin, possibly transported via the Swedish East India Company ship “Riksens Ständer” in 1762, whose cargo included 3,600 cotton fabrics of 18 different qualities, purchased during the Company’s stay in Surat. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Digitalt Museum Image, no. 17648b:300b).

Carsten Niebuhr emphasised the favourable position of Surat too in March 1764: ‘Surat is the most important port in the whole of the Mughal Empire and therefore the trade in this city is very substantial. The merchants living here, send ships to the Persian and Arab Gulf, to the African coast and to the Malabar and Coromandel coasts, even to China; and the many precious manufactures produced in the various provinces and cities of the Mughal Empire, they get to the country with large caravans…’ One of the most important goods were fine cottons in a wide range of qualities. Indian textiles was not part of Niebuhr’s collection though, but the depicted example is a well-preserved contemporary comparison – a fabric sample which was included in the Swedish professor Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) collection. This sample and a number of other cottons within the collection are regarded as of Indian origin, possibly transported via the Swedish East India Company ship “Riksens Ständer” in 1762, whose cargo included 3,600 cotton fabrics of 18 different qualities, purchased during the Company’s stay in Surat. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Digitalt Museum Image, no. 17648b:300b).Niebuhr left Surat by ship on 8 April 1764 and was back in Bombay five days later. Due to poor health, the rainy season, and other unforeseen circumstances, his stay became prolonged, and first, in December of the same year, he sailed towards Muscat.

Notice: Quotes have been translated for this essay by Viveka Hansen – from Danish to English from (Niebuhr…2003), if not otherwise stated. This is the first of three essays about Carsten Niebuhr’s textile observations from 1761 to 1767.

Sources:

- Baack, L.J., Undying Curiosity – Carsten Niebuhr and The Royal Expedition to Arabia (1761-1767), Stuttgart 2014.

- Dam-Mikkelsen, Bente & Lundbæk, Torben ed., Etnografiske genstande i Det kongelige danske Kunstkammer 1650-1800, Nationalmuseet, København 1980 (pp. 76-77, 95-96 & quote p. 95).

- Hansen, Anne Haslund, Niebuhrs Museum: Souvenirs og sjældenheder fra Den Arabiske Rejse 1761-1767, København 2016 (pp. 182-189).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Peter Forsskål’s chapter. pp. 163-178).

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. Volume One & Two. Copenhagen, 1774-1778.

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Rejsebeskrivelse fra Arabien og andre omkringliggende lande (Intr., Michael Harbsmeier), København 2003 (Vol. One & Vol. Two: pp. 19-93).

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Beskrivelse af Arabien ud fra egne iakttagelser og i landet selv samlade efterretninger (Intr., Niels Peter Lemche. quote p. 8), København 2009.

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, 1700-tals Textil – 18th Century Textile, Stockholm 1990 (Anders Berch’s collection. pp. 192-198 & 258-259).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE