ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

CLOTHES AND TEXTILE FURNISHING IN THE 1770s

– A Case Study of the Naturalist and Physician Göran Rothman

Several of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles, who returned from their long-distance natural history journeys and lived to a mature or old age in Sweden, have been possible to identify in preserved estate inventories. Amongst a multitude of possessions such documents listed linen and clothes. This essay will take a closer look at one of these individuals, the naturalist and physician Göran Rothman who returned home to Stockholm in 1776 after a three-year journey to northern Africa. An in-depth study of his travel journal, correspondence and extant legal documents reveals a rich selection of details. The aim is foremost to increase the understanding of everyday life realities during the 1770s – seen through the eyes of such contemporary documents – via textile furnishing, linen and clothes left after one single man in a Swedish bourgeois home.

A ‘View of Uppsala cathedral from the North’, which must have been a familiar view to the seventeen-year-old Göran Rothman (1739-1778) who was enrolled at Uppsala university in November 1757. Among other subjects, he studied medicine as well as natural history under Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), Rothman took three degrees between 1760 and 1763, finalising with Doctor of Medicine. (Courtesy of: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, no: 2009.142. Pen and black ink, watercolour, c. 1780s-90s by Elias Martin (1739-1818). Public Domain).

A ‘View of Uppsala cathedral from the North’, which must have been a familiar view to the seventeen-year-old Göran Rothman (1739-1778) who was enrolled at Uppsala university in November 1757. Among other subjects, he studied medicine as well as natural history under Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), Rothman took three degrees between 1760 and 1763, finalising with Doctor of Medicine. (Courtesy of: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, no: 2009.142. Pen and black ink, watercolour, c. 1780s-90s by Elias Martin (1739-1818). Public Domain).Göran Rothman was born in Huseby, Skatelöv parish, Småland province in Sweden on 30 November 1739, but he grew up in the nearby town of Växjö. The Rothman family had had academic ancestry for several generations, so also Rothman’s father, the provincial physician Johan Stensson Rothman (1684-1763), who had been Carl Linnaeus’ teacher at the gymnasium in Växjö from 1724 to 1727. After taking his degrees in Uppsala in 1763, Rothman practised as a physician in Stockholm for ten years together with several other commissions within his profession, including:

- Collegium medicum sent him – from 28 August to 23 September 1766 to Åland (an island between Sweden and Finland) – the reason was a fever of a similar kind as malaria, which raged on the island. Rothman was seen as the most capable physician in finding a cure for the illness.

- Secretary at the Collegium medicum from the years 1766-1773.

- Quarantine doctor in the Stockholm archipelago 1770-1772.

Like many of Carl Linnaeus’ former students, Rothman had great hopes to get the opportunity to make a lengthy natural history journey, and in 1773, he was seen by Linnaeus et al. as a suitable candidate to explore Tripoli and its surroundings. Rothman’s journey was financed by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and according to his travel journal, before embarking on the journey in August of that year, they also provided him with ‘proper instructions and necessary instruments such as thermometers, water-collector, water-tester, microscopes, weights, accurate measuring-rods for Swedish weight and lengths etc’. After arriving at Tripoli, the main destination in Libya – via ship from Helsingør in Denmark to Tunis in Tunisia – there were besides day trips from the city, also longer excursions undertaken over land as well as minor boat trips in the area.

His journal and contemporary correspondence, however, only include some minor notes about his clothes, which add knowledge about his conditions and everyday life from a textile perspective during a three-year-long journey. The clothes were not only necessary for enduring cold, heat or being correctly adapted for a variety of social occasions, but could also be used as bedding, which is described as follows during a trip outside Tripoli on the 1 August 1775: ‘...we lay down on the floor to sleep and made a bed of sails, cloth and clothes’. The previous year, on a tour in the vicinity of the same town, Rothman visited on 25 February 1774 a wealthy sheikh’s camp, which consisted of about 400 tents under his command. The visitor was soon regarded as a good guest, particularly as he was considered useful in his capacity as a doctor, and everybody wanted to consult him about imagined illnesses as well as actual illnesses. Judging by his journal, the Bedouins had never before met with any Europeans: ‘...people treated me as a new peculiar animal; my clothes, buttons, gloves, wig etc. was carefully examined and observed.’ To show his respect and appreciation, Rothman later presented the sheikh with a red-striped handkerchief. In a letter to the secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Pehr Wargentin (1717-1783), dated 8 April 1774, those events in the Bedouin tent were mentioned. In November of the same year, while again carrying out fieldwork outside Tripoli, Rothman experienced how surprisingly cold the nights can be in the African desert. He recorded that it was so cold that not even the Swedish winter clothes he had brought with him were enough to keep out the cold, something he had probably not expected. At the other extreme, he had problems with the heat as well. In that context, it was not the clothes themselves but the wig, which he described as overwhelmingly hot in the insufferable heat, and he began to live simply with his own hair instead.

This illustration from Tripoli gives an interesting glimpse into city life, ancient sites and the local inhabitants clothing, comparable to some of Rothman’s written observations in the 1770s. However, in his preserved journal and adjoining correspondence, little is mentioned about the materials and looks of his own clothes. The conclusion can still be drawn that he used his own European clothes and did not adopt local traditions in order better to blend into the milieu, climatically or culturally. (From: Mayer, Luigi, ‘Views in the Ottoman Dominions, in Europe in Asia, and some of the Mediterranean Islands…’, 1810. Luigi Mayer travelled in the Ottoman Empire in the period 1776-1792).

This illustration from Tripoli gives an interesting glimpse into city life, ancient sites and the local inhabitants clothing, comparable to some of Rothman’s written observations in the 1770s. However, in his preserved journal and adjoining correspondence, little is mentioned about the materials and looks of his own clothes. The conclusion can still be drawn that he used his own European clothes and did not adopt local traditions in order better to blend into the milieu, climatically or culturally. (From: Mayer, Luigi, ‘Views in the Ottoman Dominions, in Europe in Asia, and some of the Mediterranean Islands…’, 1810. Luigi Mayer travelled in the Ottoman Empire in the period 1776-1792).After his journey to Tripoli in 1776, Rothman lived on for just over two more years. This untimely death was not regarded as due to any possible after-effects of his travels, but is stated as due to gangrene in the register of deaths and burials of the parish of the Storkyrka Cathedral in Stockholm. Judging by the contents of his estate inventory, there is no indication of him having suffered economically prior to his illness, as large numbers of all necessary personal effects and clothes were listed there. It can also be seen from the estate inventory that he must have been suffering from ill health for some time, as significant sums appear under ‘Debts paid’ to ‘Mr Physician Hoffmann and the Apothecary Lars Collin according to three invoices’. His linen, bedding and everyday clothes are of great interest for detailed knowledge about his textiles, on the assumption that most of the listed garments were the same as Rothman used during his North African travels a few years earlier. It is also evident that, not belonging to the aristocracy, he complied with the then-current sumptuary law for the commoners, as no lace nor any type of luxury accessory appeared on the list. As was the case with clothes of silk being but few in number and only consisting of trousers and socks in white or black together with the odd garment made of half-silk. The following is a transcription of all the textile items which were listed in the estate inventory:

Linen

- 7 pairs Sheets of unbleached linen

- 7 pieces ditto of rough tow cloth

- 3 pieces Damask Diaper Cloths

- 4 pieces do. of tow cloth

- 30 pieces Damask Diaper Napkins

- 14 pieces do. of rough tow cloth

- 6 pieces Pillow Cases

- 16 ells new fine Damask Diaper of 5 quarters’ width

- 4 pairs striped white Curtains

- 1 Curtain with 2 valances/pelmets

- 3 pieces Shirts of brown holland

- 4 pieces ditto of rougher kind

- 10 pieces ditto with cuffs

- 6 pieces do. already cut out

- 6 pieces Nightshirts

- 3 pieces do. with cuffs

- 6 pieces old Neck scarves

- 8 pieces Handkerchiefs

- 1 pair Cuffs with a few ells of ribbon

- 3 pieces old Window Curtains

- 12 ells new Curtain material

Bedding

- 1 Feather bed with striped fustian

- 1 Long Cushion with ditto

- 1 do with blue striped bedtick

- 1 small Mattress stuffed with wool

- 1 small Head Pillow with striped fustian [continuation at second image caption below]

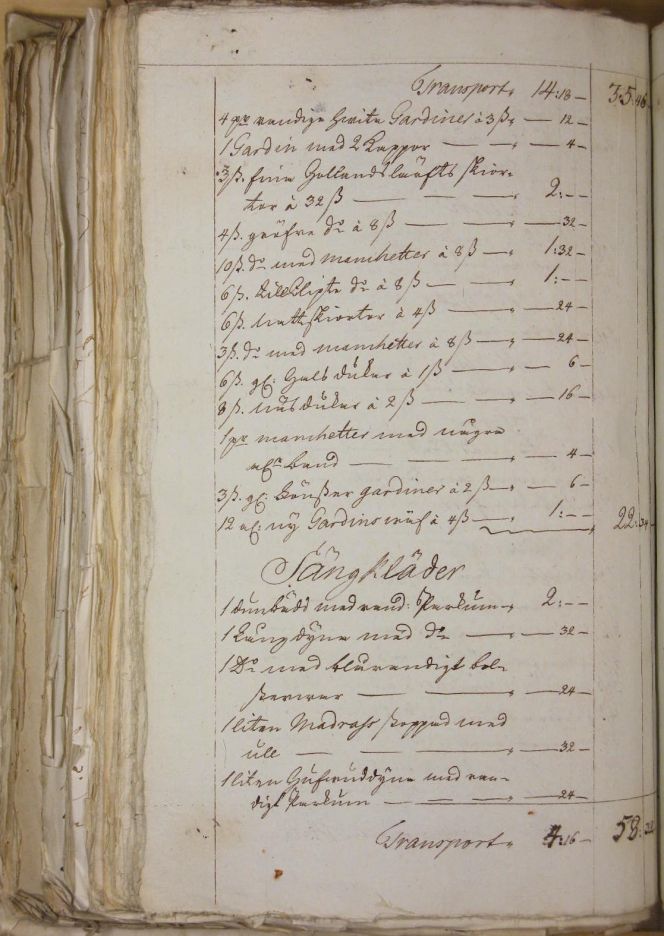

This text shows parts of the deceased’s ‘Linen’ and ‘Bedclothes’, the full text of which can be studied in a translation above and at the image caption below. (Courtesy of: Stockholms Stadsarkiv… 1779, rotel 1, no. 222 p. 4. Page four (out of ten) of Göran Rothman’s estate inventory, dated 11 March 1779).

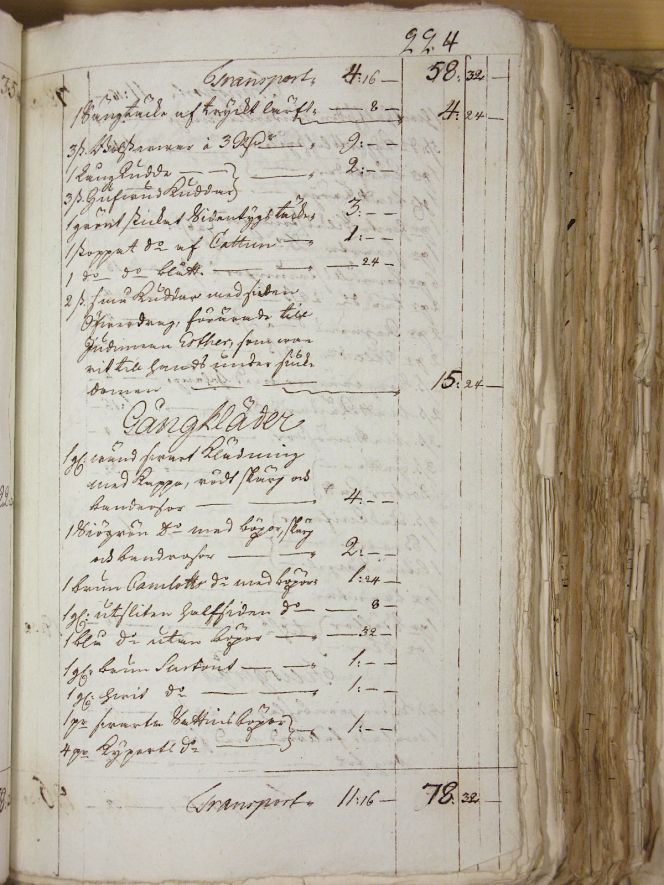

This text shows parts of the deceased’s ‘Linen’ and ‘Bedclothes’, the full text of which can be studied in a translation above and at the image caption below. (Courtesy of: Stockholms Stadsarkiv… 1779, rotel 1, no. 222 p. 4. Page four (out of ten) of Göran Rothman’s estate inventory, dated 11 March 1779). The ‘Bedclothes’ and ‘Everyday Clothes’ on this page, reads in a translation: ‘1 Bedcover of printed unbleached linen, 3 pieces chair seats, 1 long Cushion, 3 pieces Head Pillows, 1 green quilted cover of silk cloth, 1 quilted do. of fine printed calico, 1 do. do. blue, 2 pieces small cushions with silk Covers presented to the Jewish woman Esther, who had been present during his illness.’ Together with his everyday clothes: ‘1 old turned Vestment with coat, a red belt and ribbon roses, 1 sea green do. with trousers, belt and ribbon roses, 1 brown Camlet do. of thick, shiny woollen cloth with trousers, 1 brown worn out do. of half silk, 1 blue do. without trousers, 1 old brown Surtout, 1 old white do., 1 pair black Satin trousers, 4 pairs twill do.’ (Courtesy of: Stockholms Stadsarkiv… 1779, rotel 1, no. 222 p. 5. Page five (out of ten) of Göran Rothman’s estate inventory, dated 11 March 1779).

The ‘Bedclothes’ and ‘Everyday Clothes’ on this page, reads in a translation: ‘1 Bedcover of printed unbleached linen, 3 pieces chair seats, 1 long Cushion, 3 pieces Head Pillows, 1 green quilted cover of silk cloth, 1 quilted do. of fine printed calico, 1 do. do. blue, 2 pieces small cushions with silk Covers presented to the Jewish woman Esther, who had been present during his illness.’ Together with his everyday clothes: ‘1 old turned Vestment with coat, a red belt and ribbon roses, 1 sea green do. with trousers, belt and ribbon roses, 1 brown Camlet do. of thick, shiny woollen cloth with trousers, 1 brown worn out do. of half silk, 1 blue do. without trousers, 1 old brown Surtout, 1 old white do., 1 pair black Satin trousers, 4 pairs twill do.’ (Courtesy of: Stockholms Stadsarkiv… 1779, rotel 1, no. 222 p. 5. Page five (out of ten) of Göran Rothman’s estate inventory, dated 11 March 1779).Continuation of Everyday Clothes on page six of the estate inventory:

- 1 white undergarment of half silk

- 5 pieces do. twill body garments

- 1 pair hair lining

- 1 old night jacket

- 1 pair white silk stockings

- 1 pair black do.

- 6 pairs cotton socks

- 2 pairs [thread] do.

- 2 pairs do. of Worsted

- 2 pairs Wool do.

- 2 pieces mourning swords with drapes

- 2 pieces Dressing Gowns

- 3 pieces Nightcaps

- 3 pieces Hats

- 1 Doctoral Hat

- 4 pieces Shaving knives

- 1 Mirror 1 small Mirror

- 1 pair Mittens

- 1 pair Boots

- 1 pair Shoes

The 39-year-old Göran Rothman was unmarried at his demise, and it is unknown where his belongings ended up. His travel journal, correspondence, herbarium plants and some other writings are preserved up to present-day dispersed at several museum and archive collections – evident via his included name, natural history observations etc. Clothing and textiles, on the other hand, often being much more difficult to trace, if still extant, whilst it is rare to find actual proof that a particular garment, a pair of boots or a linen cloth belonged to a specific individual. To find such evidence is even rarer when a person like Rothman had no wife or children who inherited his personal belongings.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012. (Volume Four: Journal of Göran Rothman & Volume Eight, biography p. 30).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Göran Rothman – Resa till Tripoli’, (introduction, biography and transcription of his journal), SLÅ, 2012, pp. 7-84.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (The translation of the estate inventory was first published in Göran Rothman’s chapter. pp. 95-101).

- Hedlund, Emil, ‘Assessor Göran Rothman: Levnadsteckning.’ SLÅ, 1937, pp. 4-43.

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien, Bergianska Library) Stockholm, Sweden. Berg. Bibl. H:V: 3.2.n.16. ‘Göran Rothman, Resa till Tripoli år 1773–1776’ and letters to the Secretary Pehr Wargentin.

- Stockholm Town archive (Stockholms Stadsarkiv), Sweden. | ’Bouppteckningar [estate inventories] Stockholms Rådhusrätt, 1779, rotel 1, no. 222.’ & Death and Funeral book from Storkyrkoförsamlingen).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE