ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

COTTON AND OTHER TEXTILE MATERIALS

– in Thoreau’s Concord

A visit to the Concord Museum in New England, formed the inspiration for this historical essay – a well-presented and most interesting collection situated in lovely surroundings on the outskirts of Concord. A town first and foremost associated with its literary citizens – Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) and others in their transcendentalist community. The aim is to include some notes from their work connected to cotton, but primarily concentrating on the material’s everyday growing importance for larger groups of the society in the first half of the 19th century. The raw materials, local cotton mills, various cotton fabrics, and a selection of other textiles and garments exhibited at the museum are also going to be discussed briefly, to be compared and added with linked information from other nearby institutions and contemporary written works.

Cotton became an important raw material for several towns along the Merrimack River during the early Industrial Revolution. Among these, Lowell expanded to the largest textile centre, but Concord also had various firsthand connections to cotton through a number of linked historical events that had implications for the town in various ways. Massachusetts and the area surrounding the Merrimack River also belonged to the northernmost area of the so-called “cotton growing areas” which meant that cotton was successfully cultivated, but to a limited extent compared to the southern states included in the cotton belt. Other important factors for the development of early industries in the area were rich access to labour and water power from the river. The complex interplay of economic factors, demand for cotton, import or export, speed of industrialisation, slaves or free workers, etc, are just touched upon here from a few angles.

The Nineteenth-Century Chamber (1800-1820) at Concord Museum is one of several period interiors, built upon research from a variety of archival and visual sources giving the visitors an idea of the local domestic life during the 18th and 19th centuries. All exhibited fabrics are reproductions developed from studies of the town’s estate inventories, imported qualities via English sample books, upholsterer’s account books, bills of sale, original textile furnishings or fragments. This depiction of an early 19th century chamber clearly demonstrates the increasing use of printed cottons and woven upholstery fabrics. In stark contrast to the museum’s 1750s parlour interior, presenting a time when woollen cloths and checked linen qualities were primarily in use. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The Nineteenth-Century Chamber (1800-1820) at Concord Museum is one of several period interiors, built upon research from a variety of archival and visual sources giving the visitors an idea of the local domestic life during the 18th and 19th centuries. All exhibited fabrics are reproductions developed from studies of the town’s estate inventories, imported qualities via English sample books, upholsterer’s account books, bills of sale, original textile furnishings or fragments. This depiction of an early 19th century chamber clearly demonstrates the increasing use of printed cottons and woven upholstery fabrics. In stark contrast to the museum’s 1750s parlour interior, presenting a time when woollen cloths and checked linen qualities were primarily in use. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The study of everyday objects from the area is based on observations at the Concord Museum and comparisons with additional objects from the two publications listed below by Peter Benes and David Wood. It can be stated that 18th century samplers, mourning pictures and similar embroideries from the area, were primarily sewn with silk on linen, in some cases cotton or wool on linen or silk on silk was preferred. This category of textile knowledge was practised by the daughters of well-to-do families, as there was a cost for the education, and everyone could not find the many hours to complete such time-consuming ornamental needlework, buying the linen and yarn included additional expenses as well. Henry D. Thoreau’s well-to-do grandparents’ generation from the mid-18th century Boston, gives good examples for young girls' possibilities in this type of craft through several preserved samplers, mourning pictures and coats of arms of this exclusive kind. These needleworks can be exemplified with two numbers; today kept at the Concord Museum: A sampler worked with silk on a linen ground by Henry D. Thoreau’s paternal great aunt Elizabeth Orrock in 1747 and a coat of arms worked by his maternal grandmother Mary Jones about 1765 with silk and metal embroidery on silk satin ground (Wood p.95 & p.98).

Studies of textile tools like linen or wool wheels, winders, etc, in use from circa 1750s to 1820s demonstrate that these tools, almost without exceptions, were used for wool and flax, in other words, up to that time when the importance of cotton rapidly increased in mills and industries. The wealthy could, on the other hand, already in the 18th century, choose from a collection of printed or checked cotton fabrics primarily imported from England. At the same time, “ordinary people”, to a lesser extent, had the means to buy the costly goods. An alternative to the fashionable cotton fabrics was to spin and weave flax or wool for their family’s needs, which these preserved tools, among other sources, are proof of.

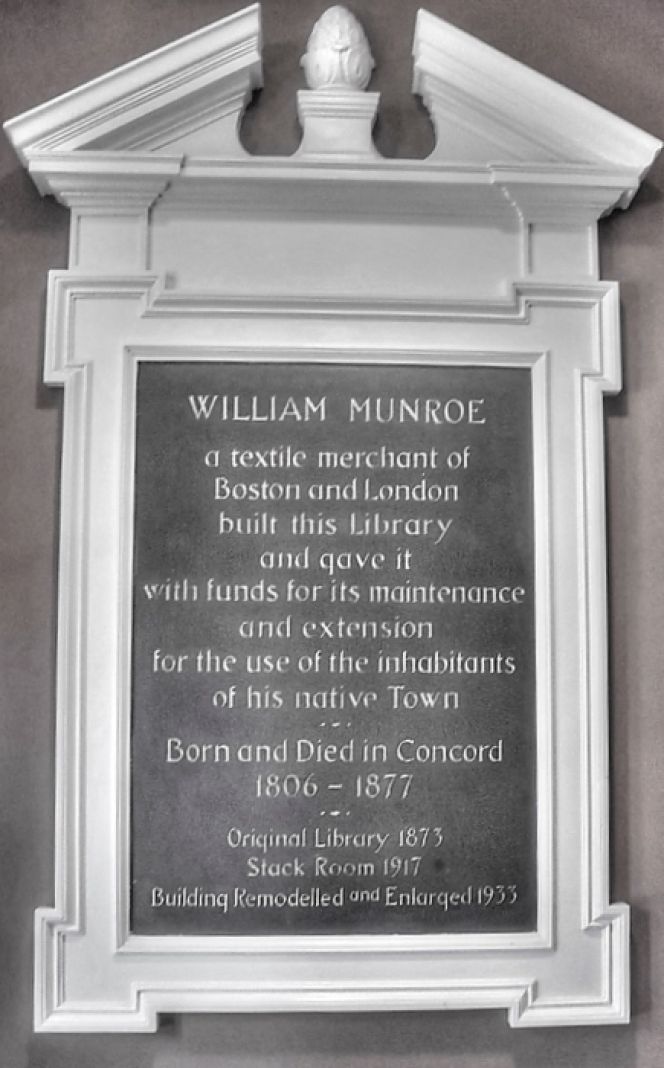

William Monroe (1806-1877) lived in Concord up to his apprentice period, when at the age of 15 he moved to Boston. As the plaque at Concord Free Public Library explains he worked in London as well as Boston during his working life as a textile merchant. This was a prosperous trade making him a wealthy man, leading up to that after his retirement in 1861 the devotion to his birth place became stronger. He invested in properties and laid out new streets, but Monroe is foremost remembered for funding the new library building and securing the free public library’s future existence. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

William Monroe (1806-1877) lived in Concord up to his apprentice period, when at the age of 15 he moved to Boston. As the plaque at Concord Free Public Library explains he worked in London as well as Boston during his working life as a textile merchant. This was a prosperous trade making him a wealthy man, leading up to that after his retirement in 1861 the devotion to his birth place became stronger. He invested in properties and laid out new streets, but Monroe is foremost remembered for funding the new library building and securing the free public library’s future existence. Photo: The IK Foundation, London. These well-preserved leather breeches dating from about 1793 displayed at the Concord Museum also have a connection to the textile merchant William Monroe, while the garment once belonged to a contemporary apprentice working in the Boston area. Leather as a material was overall seen as the toughest and most durable material within many trades, when sewn together with the tiniest stitches as this pair demonstrates. The museum also emphasises: ‘In his autobiography, William Monroe recorded that taking care that the apprentices’ clothing was in good order was the responsibility of the women in the cabinetmaker’s household’. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

These well-preserved leather breeches dating from about 1793 displayed at the Concord Museum also have a connection to the textile merchant William Monroe, while the garment once belonged to a contemporary apprentice working in the Boston area. Leather as a material was overall seen as the toughest and most durable material within many trades, when sewn together with the tiniest stitches as this pair demonstrates. The museum also emphasises: ‘In his autobiography, William Monroe recorded that taking care that the apprentices’ clothing was in good order was the responsibility of the women in the cabinetmaker’s household’. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Quilts of various designs became more and more common when the 19th century advanced, another clear indication for that larger quantities of cotton fabrics were in circulation for various uses when reaching the mass consumer in the 1830s and 1840s. A guided tour at Ralph Waldo Emerson’s house also made clear that this home owned cotton quilts of complex designs, most probably dated from the second half of the 19th century, and the Concord Museum is additionally keeping a collection of cotton quilts and sewing tools. Studies of portraits, cotton garments, estate inventories, correspondence and other primary sources can give further clues to the development of cotton in the Concord area. Furthermore, to work in a cotton mill became a possibility for young women to find work, another was as a seamstress at home. This a path that the young Louisa May Alcott chose during a period in her young life while the seamstress work assisted the family’s poor economy – she is otherwise most known for her novel Little Women and as one of Concord’s literary elite.

It can also be stated that the rapid change for cotton in everyday clothing and home furnishing made laundering less complex; it became easier to keep up good hygiene for families and cheaper to purchase clothes. This increasing availability of the raw material and growing speed of manufacturing of cotton cloth, is also evidence for that the amount of garment each and every person owned during their lifetime was enlarged for all groups in society, with exception for the poorest. This was a reality during the 19th century Industrial Revolution in the Concord area of Massachusetts, just as in many comparable states in the US and also, for example, in some European countries.

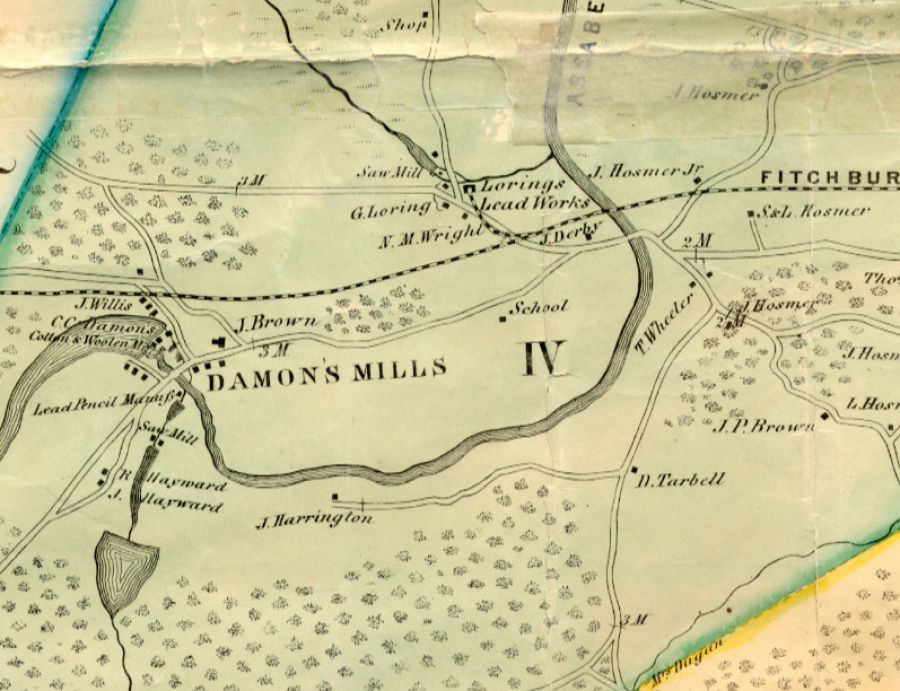

A section of the Concord “Walling Map” from 1852 illustrating the Damon Mill, which was at the time owned by Calvin Carver Damon. Two years later the running of the cotton mill was handed over to his son Edward Carver Damon whose daily work and dedication among other facts are described at the Concord Museum’s History gallery: ‘…made him the town’s largest employer, with as many as 175 workers… Damon was deeply involved in community life. He served on town committees, attended the lyceum, and became a friend of Emerson and Thoreau’. Further more the mill was in his ownership up to 1898 and this textile manufacturing was recognised in particular for a wool-cotton like flannel cloth invented by his father. It can also be noted from research by the Public Free Library that a fulling mill was situated at the same ideal riverside location, long before cotton spinning was introduced here in the early 19th century. Courtesy of map: Concord Public Free Library, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.

A section of the Concord “Walling Map” from 1852 illustrating the Damon Mill, which was at the time owned by Calvin Carver Damon. Two years later the running of the cotton mill was handed over to his son Edward Carver Damon whose daily work and dedication among other facts are described at the Concord Museum’s History gallery: ‘…made him the town’s largest employer, with as many as 175 workers… Damon was deeply involved in community life. He served on town committees, attended the lyceum, and became a friend of Emerson and Thoreau’. Further more the mill was in his ownership up to 1898 and this textile manufacturing was recognised in particular for a wool-cotton like flannel cloth invented by his father. It can also be noted from research by the Public Free Library that a fulling mill was situated at the same ideal riverside location, long before cotton spinning was introduced here in the early 19th century. Courtesy of map: Concord Public Free Library, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.Henry D. Thoreau cannot only be associated with textile materials via his grandmother’s and other female relatives’ exquisite needleworks, his rich collection of observations in publications, journals and correspondence also opens up opportunities to study textiles or various raw materials. Besides that, Thoreau, for example, made contemporary notes about cotton, clothing and the early textile industry in the area; he was also historically interested in the 18th century. A notation of this kind can be studied in his journal Volume Six from 1854 when old account books were at the centre of his attention. David F. Wood also makes some valuable comments and quotes on this matter: ‘He studied them with care. “I have an old account-book, found in Deacon R. Brown’s garret since his death…Its cover is brown paper, on which, amid many marks and scribbling, I find written:/Mr. Ephraim Jones/His Wast Book/Anno Domini/1742.” After noting that the commonest entries were for mohair, buttons…’ (Wood, pp. 29-30). It is also emphasised that Thoreau, long before his time, made observations on what today is regarded as the discipline of “Material Culture”. However, it must be noted that textiles and their various raw materials had a comparably minor role within his journals than, for example, wooden objects and their everyday importance for the citizens.

As a brief case study, I have searched for the word “cotton” in Thoreau’s digitised journals dating from 1854 to 1861, where it is evident that he connected to the material in various ways, but only quite occasionally. It must be noted that “cotton” on repeated occasions was used as a comparison in the terms “cottony”, “cottoned”, or “cotton-like” for his detailed studies of nature. He, on the other hand, quite rarely wrote something descriptive about cotton fabrics or the raw material, and if so, mostly in passing.

Below, the information is recorded from this journals, demonstrating his various interests in cotton (the cotton item etc., marked in bold).

Oct. 7, 1854:

‘Went to Plymouth to lecture––& survey Watsons Grounds. Returned the 15th…. Measured a buck-thorn on land of N. Russell & Co, bounding on Watson—close by the ruins of the cotton factory…’ (Vol. 18)

Febr. 28, 1855:

‘…that thread they wipe the locomotive with “cotton waste” & one real thread all as it were woven into a perfect bag.’ (Vol. 18)

March 22, 1855:

‘…found a flying squirrel in it, which as my left hand covered a small hole at the bottom ran directly into my right hand. It struggled & bit not a little, but my cotton gloves’ (Vol. 18)

Dec. 5, 1856:

‘The Indians have at length got a regular. It is odd to see a pile of good oak wood beside their thin cotton tents in the snow– the woodpile which is to be burnt within is so much more substantial than the house. Yet they do not appear to mind the cold’ (Vol. 22)

March 13th, 1857:

‘Phus Toxicodendron p 363 of “The juice which exudes on plucking the leaf-stalks from the stem of the R. radicans is a good indelible dye for marking linen or cotton.”’ (Vol. 22)

June 27th, 1857:

‘I cannot find one of the 3 bits of white cotton string which I tied to willows in that neighborhood in the spring—&’ (Vol. 23)

July 1857:

‘Our tent was of thin cotton cloth— & quite small forming with the ground a triangular prism so that we could not begin to stand up in it… He wore a dirty cotton shirt–a greenish but no waist coat flannel one over it— strong flannel drawers—& strong ap. linen or duck pants which had been white–blue woolen stockings & cowhide boots…’ (Vol. 23)

24 July-Nov. 1857:

‘…see how much of a shelter our thin cotton tent was going to be–of what service on this excursion…’ (Vol. 24)

Dec. 6 1859:

‘Yesterday it froze as it fell on my umbrella—converting the cotton cloth into a thick stiff glazed sort of oil cloth–so that it was impossible to shut it.’ (Vol. 28)

February 15-July 22 1860:

‘A cat bird has her nest in our grove, we cast out strips of white cotton cloth–all of which she picked up & used. I saw a bird flying across the street with so long a strip of cloth…’ (Vol. 31)

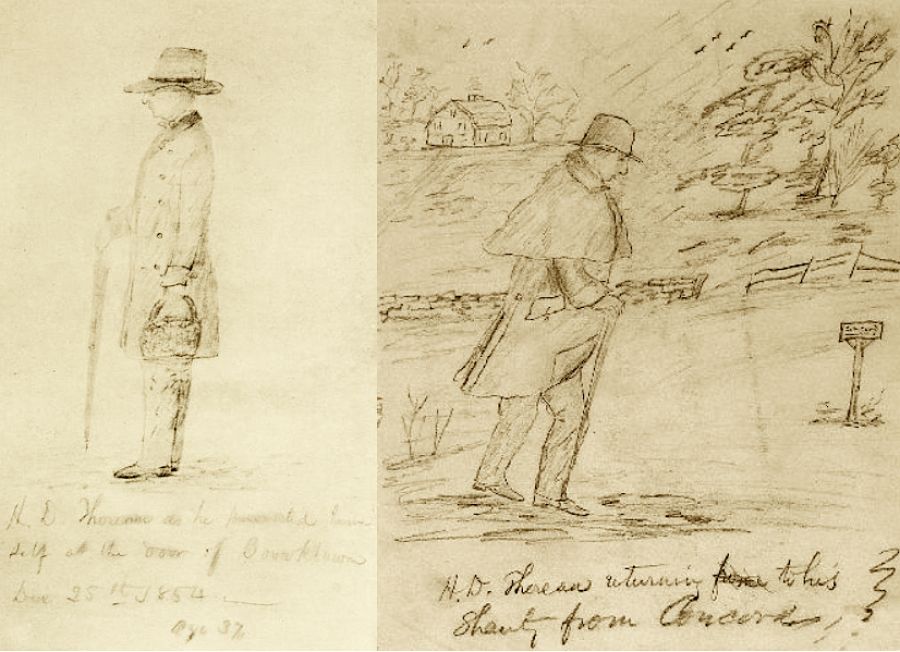

Two separate sketches in pencil on paper by Daniel Ricketson depicting Henry David Thoreau; in close detail showing his style of dress on two occasions. To the left: Thoreau at the age of 37, with the exact dating – December 25, 1854 – dressed in practical and warm clothing also including his umbrella, possibly the same which was mentioned being of ‘cotton cloth’ in his Journal on December 6, 1859 (please see quote above). To the right: This sketch is undated, but includes an informative text ‘H.D. Thoreau returning to his Shant from Concord’. Even here the clothing is warm and practical, observe the cape-like addition to his coat. Courtesy of: New Bedford Whaling Museum, Massachusetts, U.S (Daniel Ricketson’s sketchbook, 00.210).

Two separate sketches in pencil on paper by Daniel Ricketson depicting Henry David Thoreau; in close detail showing his style of dress on two occasions. To the left: Thoreau at the age of 37, with the exact dating – December 25, 1854 – dressed in practical and warm clothing also including his umbrella, possibly the same which was mentioned being of ‘cotton cloth’ in his Journal on December 6, 1859 (please see quote above). To the right: This sketch is undated, but includes an informative text ‘H.D. Thoreau returning to his Shant from Concord’. Even here the clothing is warm and practical, observe the cape-like addition to his coat. Courtesy of: New Bedford Whaling Museum, Massachusetts, U.S (Daniel Ricketson’s sketchbook, 00.210).Henry D. Thoreau’s thoughts on ‘Clothing’ in the chapter about Economy in Walden is also of great interest from a textile point of view. Contemporary and past fashions and clothing ideals are scrutinised here by his observant eye and his wishes to simplify and slow down the speed of changing fashions. Some of his conclusions will exemplify his ideas on the subject:

‘The childish and savage taste of men and women for new patterns keeps how many shaking and squinting through kaleidoscopes that they may discover the particular figure which this generation requires today. The manufacturers have learned that this taste is merely whimsical. Of two patterns which differ only, by a few threads more or less of a particular colour, the one will be sold readily, the other lie on the shelf, though it frequently happens that after the lapse of a season the latter becomes the most fashionable…I cannot believe that our factory system is the best mode by which men may get clothing. The condition of the operatives is becoming every day more like that of the English; and it cannot be wondered at, since as far as I have heard or observed, the principal object is, not that mankind may be well and honestly clad, but, unquestionably, that the corporations may be enriched. In the long run men hit only what they aim at. Therefore, though they should fail immediately, they had better aim at something high.’ (pp. 26-27).

The author, during fieldwork within the Bridge Builder Expedition – North America, by Walden Pond in July 2014. Close-by to where Thoreau’s cabin once was situated, on the site for his daily life and work during two years, starting from the summer of 1845. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The author, during fieldwork within the Bridge Builder Expedition – North America, by Walden Pond in July 2014. Close-by to where Thoreau’s cabin once was situated, on the site for his daily life and work during two years, starting from the summer of 1845. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.It was not in Walden alone that his thoughts on the growing textile industry appeared; other of his publications and, in particular, his Journals include observations of this kind. A paper by John S. Pipkin also reveals many thoughts on the effects on both the environment and humans, as studied by Thoreau. He showed hesitation for the rapid expansion of the development as well as, in some cases, admiration for the mechanical revolution and the possibilities for work. For example, in Thoreau’s book The Week, there is a worry about new implications of noise from the industries and the expanding interference of man in nature: “the artificial falls where the canals of the Manchester Manufacturing Company discharge themselves into the Merrimack…But we did not tarry to examine them minutely, making haste to get past the village here collected, and out of hearing of the hammer which was laying the foundation of another Lowell” (Pipkin pp 31-32, quote from Chapter 6, the Week). Pipkin also gives an example from Thoreau’s Journal of 1851 describing ‘unqualified enthusiasm’ for a cotton mill built in 1843 by Bigelow, a few miles west of Concord. Where: ‘He visits pattern rooms and looms and is extremely impressed by the machinery and by the quality control exercised the mill girls, sisters of the regimented, chaperoned, barracked and much-studied workforce of Lowell’ (Pipkin p. 32). When Thoreau visited the mill on this occasion, it produced cotton fabrics and various textiles, like carpets, tweed, lace, gingham, etc.

Thoreau’s rich observations give a great variety of thoughts on mid-19th century traditions and historical ideas of clothing, fashion and useful textile materials. Journals, correspondence, and publications have also been quoted from an astonishing number of angles for many years. A relatively new and interesting book is even named The Quotable Thoreau, from which a quote so typical of his thoughts on clothing has been selected – mentioning the man who depicted Thoreau in pencil on paper at least twice.

‘I have just got a letter from Ricketson, urging me to come to New Bedford, which possibly I may do. He says I can wear my old clothes there.’ (Cramer, ed. p.69, originally from The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau).

Sources:

- Benes, Peter, Two Towns Concord & Wethersfield – A Comparative Exhibition of Regional Culture 1635-1850, Concord 1982.

- Concord Museum, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S (Visit in 2014: Bridge Builder Expeditions – North America The IK Foundation)

- Cramer, Jeffrey S., ed., The Quotable Thoreau, Princeton University Press 2011.

- New Bedford Whaling Museum, Massachusetts, U.S (Daniel Ricketson’s sketchbook, images online).

- Pipkin, John S., ‘Working on the Concord and Merrimack: Thoreau’s Mills’, Middle States Geographer, 2004, 37: 29-37.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson House, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. (Visit in 2014: see Concord Museum).

- The Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. (Visit in 2014: ditto). & Facts about William Munroe Jr. & the Damon Mill.

- The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau: Digital source (search term “cotton” in the available Journal Manuscripts; September 3, 1854 – November 3, 1861.)

- Thoreau, Henry D., Walden (With an introduction by John Updike), Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Wood, David F., An observant Eye – The Thoreau Collection at the Concord Museum, Concord 2006.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE