ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

CROCHET IN SWEDEN

– Influences and Traditions: 1840s to 1910s

Crochet was first known around the year 1800 in Sweden, at the time of an increased import of cotton; the technique and the use of cotton were mainly influenced by cultural traditions in the Mediterranean area. From a Swedish perspective, crochet came to be regarded as modern and fashionable during most of the 19th century, spreading from bourgeoise ladies to broader groups in society over time. The favoured pattern combinations for crochet laces foremost originated in German and British crochet manuals. Crochet was ideal for small-sized handicraft projects, with a crochet needle and yarn only – to be used at home, when visiting friends or sitting outdoors and popular to learn as an educational needlecraft for girls alike. This essay will look closer at such handicraft skills, which resulted in accessories for clothing and textile furnishing with a wide range of usefulness. A case study, assisted by my own collection of crochet lace, specially adapted cotton yarns for crochet in its original packaging, contemporary photographs, newspaper adverts and some historical sources linked to shopping during this period.

A crochet lace, dated circa 1900, was used as an inset decoration on a cotton bedsheet in the same manner as linen bobbin laces had embellished the linen bedsheets a hundred years earlier. The handcrafted cotton crochet lace was carefully machine-stitched onto the plain cotton bedsheet. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

A crochet lace, dated circa 1900, was used as an inset decoration on a cotton bedsheet in the same manner as linen bobbin laces had embellished the linen bedsheets a hundred years earlier. The handcrafted cotton crochet lace was carefully machine-stitched onto the plain cotton bedsheet. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.This form of handicraft – made with a metal, wood or bone needle with a hook at one end – had great attention to detail and a rich variation in the patterning. The very fine metal needle was needed for the crochet laces and tablecloths examined in this essay. The increasing industrialisation made it possible to produce specially adapted machine-spun cotton yarns of various fineness in ever more significant quantities, together with the technical advancements in the printing of patterns in books, magazines and fashion journals; these were some of the essential causes for the relatively rapid rise in popularity of crocheting in several countries. As mentioned initially, crochet designs/pattern books were introduced in Germany and Britain in the early 19th century; by 1840, pattern manuals of various kinds were widespread, at a time when crochet manuals also came to be published in Sweden. As stressed by Hanna Bäckström, who has done in-depth research about crochet and knitting patterns in the mid-19th century in her thesis (published in 2021), such manuals could be divided into three categories. Firstly, in the form of short booklets from 1843 and 1846, with written instructions assisted by black and white illustrations; these were followed in the late 1840s by more voluminous and comprehensive manuals, which either could be purchased in a shop or the customer could have it sent by post, two of these in a series of thirteen instalments. A third category was introduced in the early 1850s when crochet patterns became a regular feature in fashion journals – together with other handicraft instruction for needlework, knitting, etc.

Examples of crochet lace circa 1900. The repetitive ornamentation made it a particularly suitable handicraft for all sorts of occasions. Several metres of the same design were useful for home furnishing and fashionable clothing alike. Keeping the crochet lace rolled up during work when the lace was crocheted from side to side seems to have been a common practice. This is also clearly visible in the photograph below. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Examples of crochet lace circa 1900. The repetitive ornamentation made it a particularly suitable handicraft for all sorts of occasions. Several metres of the same design were useful for home furnishing and fashionable clothing alike. Keeping the crochet lace rolled up during work when the lace was crocheted from side to side seems to have been a common practice. This is also clearly visible in the photograph below. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Studio portrait of a lady by the photographer Wilhelmina Lagerholm (1826-1917) in Örebro, Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 92638. Public Domain).

Studio portrait of a lady by the photographer Wilhelmina Lagerholm (1826-1917) in Örebro, Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 92638. Public Domain).This mid-1860s picture of an unidentified lady visualises a well-to-do individual with her ongoing crochet lace neatly rolled up, placed on the table, with the crochet needle in her right hand. Overall, in the early period of studio portraits, it was particularly vital to choose poses and expressions to show the subject’s most attractive sides and most desirable character traits in the best possible light and backgrounds and accessories could be used to draw attention to the subject’s social status or station in society.

Whilst this outdoor photograph was taken about forty years later, in 1906, it shows three middle-class ladies – maybe three generations – in a garden or park milieu. Notice the ongoing work with crochet lace in the elderly lady’s lap. This was when snapshot photographs became in demand, and more and more people of the upper- and middle classes owned cameras to immortalise family moments. Crochet, for instance, was not seldom, intentionally or unintentionally, included in such pictures. (Courtesy: Smålands Museum, Sweden. NIDA0211. DigitaltMuseum & added modern digital colouring).

Whilst this outdoor photograph was taken about forty years later, in 1906, it shows three middle-class ladies – maybe three generations – in a garden or park milieu. Notice the ongoing work with crochet lace in the elderly lady’s lap. This was when snapshot photographs became in demand, and more and more people of the upper- and middle classes owned cameras to immortalise family moments. Crochet, for instance, was not seldom, intentionally or unintentionally, included in such pictures. (Courtesy: Smålands Museum, Sweden. NIDA0211. DigitaltMuseum & added modern digital colouring). Even if crochet edges are more visible in early photographs than tablecloths in the same technique, the latter seems to have been just as in vogue and illustrated with three examples. The two small circle-shaped models were worked from the centre and outwards, round and round to the desired size – the motif combinations were almost endless. The larger model, partly illustrated, was instead crocheted in many small circles of the same design and then stitched and crocheted together – with a spindle-shaped motif – when the acquired amount of small circles had been made. This particular tablecloth has five times seven (35) circles. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Even if crochet edges are more visible in early photographs than tablecloths in the same technique, the latter seems to have been just as in vogue and illustrated with three examples. The two small circle-shaped models were worked from the centre and outwards, round and round to the desired size – the motif combinations were almost endless. The larger model, partly illustrated, was instead crocheted in many small circles of the same design and then stitched and crocheted together – with a spindle-shaped motif – when the acquired amount of small circles had been made. This particular tablecloth has five times seven (35) circles. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. This well-preserved sample collection of crochet lace by Jenny von Rothstein in Stockholm dates from 1890-1909. It shows another perspective on crochet laces. It was seen as a practical way to extend one’s knowledge of various motif combinations, probably by saving a sample of each made lace and sharing the lace samples between friends. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0252447. DigitaltMuseum).

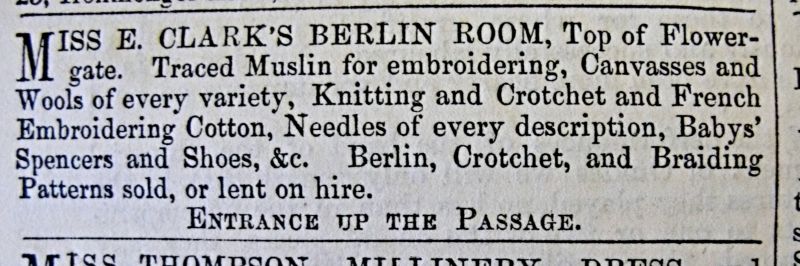

This well-preserved sample collection of crochet lace by Jenny von Rothstein in Stockholm dates from 1890-1909. It shows another perspective on crochet laces. It was seen as a practical way to extend one’s knowledge of various motif combinations, probably by saving a sample of each made lace and sharing the lace samples between friends. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Sweden. NM.0252447. DigitaltMuseum). Given that one of the countries that initially predated the Swedish “crochet craze” and from where many crochet manuals were imported to Swedish customers, the technique also continued to be popular in England over the 19th century. In the coastal town of Whitby, for instance, locals or visitors could buy crochet and embroidery materials at ‘Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room’, evident via repeated adverts in the local newspaper. | Advertisement in Whitby Gazette, April 1860. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Given that one of the countries that initially predated the Swedish “crochet craze” and from where many crochet manuals were imported to Swedish customers, the technique also continued to be popular in England over the 19th century. In the coastal town of Whitby, for instance, locals or visitors could buy crochet and embroidery materials at ‘Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room’, evident via repeated adverts in the local newspaper. | Advertisement in Whitby Gazette, April 1860. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Miss Clark was a frequent advertiser from 1855 to 1864 – this announcement is from 1860 – and she may already have been active before the founding of Whitby Gazette. In the newspaper's second year, in July 1855, ‘Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room, Top of Flowergate’ offered ‘Wools and Canvasses of every variety’ for sale. An advertisement of April 1861 also provided ‘Traced muslin for embroidering’ and ‘Berlin, Crochet and Braiding Patterns sold or lent on hire.’ The enlightening note that it equally was possible for the crochet-interested ladies to either buy or lent-on-hire such patterns indicates that prices for patterns were reasonably high. The lent-on-hire option made it possible for more female customers to keep up with fashionable crochet designs for decorative edgings on clothing, small tablecloths or other furnishing textile objects.

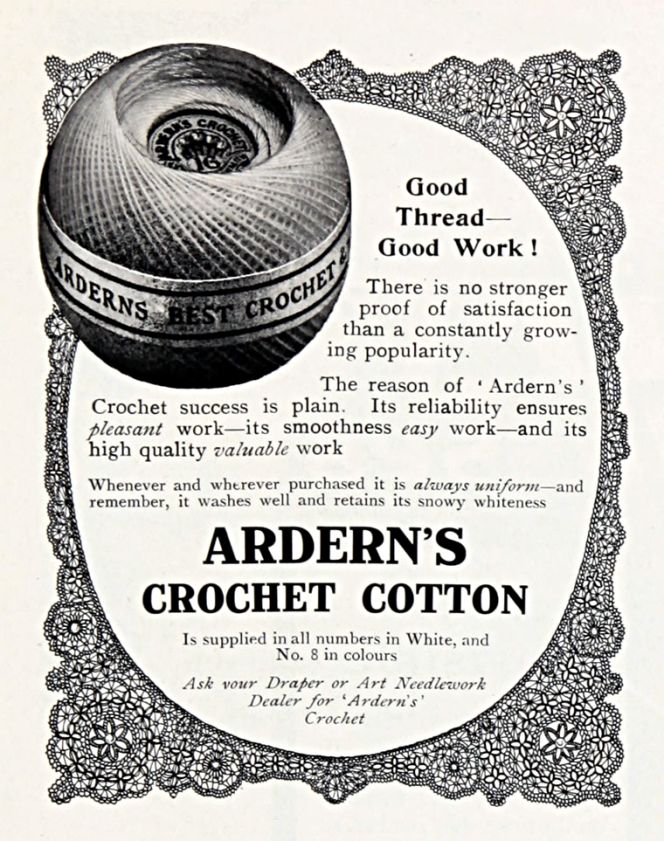

Ardern’s Crochet cotton came in three thickness qualities—20, 26, and 36—of which the highest number is the finest. All three are very fine yarns, suitable and popular for crochet laces and tablecloths in the early 20th century. Interestingly, it compares with the advert below, which gives more information about this particular yarn. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Ardern’s Crochet cotton came in three thickness qualities—20, 26, and 36—of which the highest number is the finest. All three are very fine yarns, suitable and popular for crochet laces and tablecloths in the early 20th century. Interestingly, it compares with the advert below, which gives more information about this particular yarn. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. This is a 1910 advert of Ardern’s Crochet – unknown in which newspaper or magazine. Judging by the fact that the same cotton qualities illustrated above were purchased in a Swedish bric-a-brac shop in the 1990s, the yarns must either have been sold in Sweden in the early 20th century or acquired in England around the time of this advert. (Image: Wikimedia Commons).

This is a 1910 advert of Ardern’s Crochet – unknown in which newspaper or magazine. Judging by the fact that the same cotton qualities illustrated above were purchased in a Swedish bric-a-brac shop in the 1990s, the yarns must either have been sold in Sweden in the early 20th century or acquired in England around the time of this advert. (Image: Wikimedia Commons). ![In a final picture, assisted by a word search of newspapers via the National Library of Sweden, the word ‘virkning’ [crocheting] gives an informative and selected appearance of a word, but even so, a surprisingly accurate perspective of the most intensive period of popularity for crochet. 1842 was the very first year it was included. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Online: Svenska dagstidningar; search word: ‘virkning’ 1727-1920. Quotes in translation).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/10a-virkning-svenska-dagstidningar-800x449.png) In a final picture, assisted by a word search of newspapers via the National Library of Sweden, the word ‘virkning’ [crocheting] gives an informative and selected appearance of a word, but even so, a surprisingly accurate perspective of the most intensive period of popularity for crochet. 1842 was the very first year it was included. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Online: Svenska dagstidningar; search word: ‘virkning’ 1727-1920. Quotes in translation).

In a final picture, assisted by a word search of newspapers via the National Library of Sweden, the word ‘virkning’ [crocheting] gives an informative and selected appearance of a word, but even so, a surprisingly accurate perspective of the most intensive period of popularity for crochet. 1842 was the very first year it was included. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Online: Svenska dagstidningar; search word: ‘virkning’ 1727-1920. Quotes in translation).One example can be found in the Stockholm paper ‘Stockholms Dagblad’ (13 October 1842), which is an advert informing that a French lady gives education to ‘daughters of good families’ 15 hours a week in the ‘Silk shop, house no. 8 Drottning gatan [Queen street]’, with monthly payments. Her curriculum included the French language, Oriental painting and several handicraft techniques – crochet was one of these subjects. The graph visually demonstrates that ‘crocheting’ was continuously included in newspaper adverts and articles in the following two decades. In the mid-1870s, the interest in such handicrafts must have increased further to reach its peak in 1887 with more than 1000 hits. The great demand for crochet manuals, yarns, tools and educational courses decreased in the early 20th century, and the final year for this case study, 1919, only shows 15 hits for ‘crocheting’.

An unexpected effect that crochet occurred during the 20th century within the Swedish Handicraft Organisation, even up to the 1980s, was that the technique had a low status; it was not regarded as a “proper handicraft”. This is evident via my own experience when working at the handicraft organisation in Malmö in southernmost Sweden at that time – which, since the start in 1905, had built its foundation on the rich textile traditions of the farming communities in Skåne province. The actual reason for the small interest and lack of curiosity about crochet may have had several causes. However, crochet lace and other objects made with this technique had, with few exceptions, not been part of the local textile tradition, such as knitting, embroidery, art weaving, or bobbin lace making – all with roots centuries back in time. Crochet had instead been introduced in Sweden as late as the 1840s when it first and foremost was categorised as a new fashionable pastime, suitable for ladies of the middle and upper classes, to be learned via surprisingly costly crochet manuals and fashion magazines. Or as discovered via newspaper adverts – as Stockholms Dagblad quoted above in 1842 – suitable to be mastered skilfully via educational courses for daughters of good families.

Sources:

- Bäckström, Hanna, Förmedling av mönsterförlagor för stickning och virkning: Medierna, marknaden och målgruppen i Sverige vid 1800-talets mitt, Uppsala 2021.

- DigitaltMuseum, Sweden. Online source. (Study of photographs depicting crocheting women and crochet samples, the 1850s-1920s).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 315-16).

- Hansen, Viveka (A private collection of crocheted tablecloths, laces, cotton yarns, and tools).

- Hennings, Emma [pseudonym Charlotte Leander], Nya mönster till spets-stickning m.m. samt spets-virkning, Stockholm 1846.

- Kungliga Biblioteket [National Library of Sweden]. Online: Svenska dagstidningar (search word: ‘virkning’ 1727-1920. Accessed 28 January 2022).

- Malmöhus Läns Hemslöjdsförening, Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhus Län, Malmö 1916-1923.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd: den svenska hemslöjden fram till 1800-talets slut, Lund 1969 (pp. 286-91).

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive (Whitby Lit. & Phil.), Whitby Gazette 1855-1865.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE