ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

DAILY LIFE AT A MANOR HOUSE IN 1758

– an Introduction

In one of my earlier projects – published in 2004 – a document originating from 1758 at Christinehof Manor House in southernmost Sweden provided a basis for the research. This 18th century inventory list will be presented in a total of thirteen essays giving numerous examples of material culture, domestic economies, standard of living and everyday life from a perspective of a wealthy noble family. In this hand-written manuscript the reader can follow the interior details from room to room over three floors in the manor house. Among the various furnishing, such as chairs and sofas, tables, chests of drawers, curtains, beds, wall-coverings, etc – textiles of all kinds played an important role in comfort, warmth, status, decorative purposes and value of inheritance for the family.

In 1737 the construction of a three-story manor house with two wings and attic was started in a rural location outside the village of Andrarum in southernmost Sweden. The house was completed in the autumn of 1741 for the wealthy Christina Piper, who at the time was also the owner of the close-by Andrarum alum works. Alum, so important as a mordant for textile dyeing among many uses. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

In 1737 the construction of a three-story manor house with two wings and attic was started in a rural location outside the village of Andrarum in southernmost Sweden. The house was completed in the autumn of 1741 for the wealthy Christina Piper, who at the time was also the owner of the close-by Andrarum alum works. Alum, so important as a mordant for textile dyeing among many uses. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.From 1741, when the newly-built manor house was described in a protocol, and up to the inventory dating from the late 1750s, scattered knowledge about life at Christinehof can be gleaned from preserved accounts, letters and shares. In 1758, it was the count and tenant in tail Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770) and his wife Ulrika Christina Mörner of Morlanda (1709–1778) who lived at Christinehof manor house, from July to October this particular year, according to a hand-written document of used firewood etc. The family-owned several manor houses in Sweden, but their main home was in Stockholm. The listing in the 1741 protocol was introduced with the first floor, including rooms of the count and countess. The Hall was the central room, and in 1758, the countess’ areas were situated to the left and the count’s to the right of the Hall. On this floor – besides the couple’s drawing-rooms, bed-chambers and cabinets – additional areas constituted the Young Lady’s Chamber and the son Count Adolf’s Chamber. Maids and valets lived close by to be at service at all times. Additionally, as necessary, Wardrobes and Contoir (pharmacy) were mentioned in the inventory.

The second floor was more or less a reflection of the first; apart from that, the Hall was grander and spanned the entire building. Various rooms on both sides of the Hall were named, probably after visiting relatives and friends. For instance Baron Unger’s Chamber, whilst other rooms were mentioned by the colours of which they were decorated – the Green Hall or the Blue Chamber.

The ground floor was more diverse, with domestic spaces for the household with a kitchen, larder, bakery, and brewing house, together with quarters for the cook, housekeeper, inspector, footman, court chaplain and tutor. But included were also The Counts’ Chamber, His Excellency’s Small Writing Chamber and The Vault, which housed everything from kitchen tools to woven tapestries. Through the very minute descriptions in this inventory, the daily life of a wealthy noble family in the 1750s Sweden comes to life.

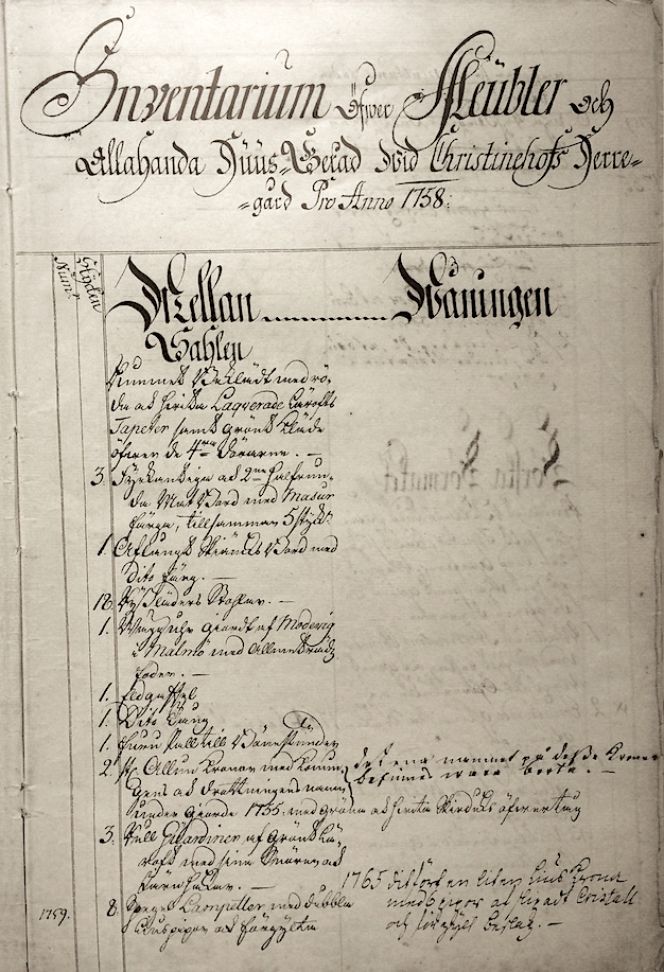

The first page of the ‘Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758’. (Courtesy of: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family archive, no D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The first page of the ‘Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758’. (Courtesy of: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family archive, no D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London. Interior painting by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816), depicting a late 18th century milieu from the higher nobility in Sweden. A lady is working or inspecting an embroidery at her frame, whilst a second lady holds a candle stick. Even if this painting dates a few decades later than the inventory, Hilleström’s portraying of a wealthy home and the sparse lighting after dark can easily be compared with similar circumstances at Christinehof manor house. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 2452, Wikimedia Commons).

Interior painting by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816), depicting a late 18th century milieu from the higher nobility in Sweden. A lady is working or inspecting an embroidery at her frame, whilst a second lady holds a candle stick. Even if this painting dates a few decades later than the inventory, Hilleström’s portraying of a wealthy home and the sparse lighting after dark can easily be compared with similar circumstances at Christinehof manor house. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 2452, Wikimedia Commons).The following essays in this new series will primarily focus on textile materials of all variants and tools used for handicrafts. These often costly textiles were not only chosen for their decorative significance but for utilitarian purposes, an aspect of vital importance. Thick wadded quilts helped to retain warmth, while thick curtains helped keep out draughts. It was only from the point of view of decorative luxury that the household’s financial state would mirror the differences in the choice of textile furnishings. The richer the manor house, the greater the quantity of exclusive silk fabrics, woven carpets, imposing bed canopies with matching fittings, and thick hand-worked rugs. Most of such manor houses reveal a rich treasure of textiles stretching back over decades and sometimes centuries at a time when it was essential to preserve the history of the family for the future, together with its store of textiles valuable in themselves. Thus, a home like Christinehof Manor House would often possess a historical spectrum of textiles, both Swedish-made and from leading continental workshops or imported from distant countries via the East India trade.

Notice: Quotes translated from Swedish to English. A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For full Bibliography & information about the project; please see Viveka Hansen’s book, 2004 (pp. 7-9 & 38-62).

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd sid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof (Piper Family archive, no D/Ia & F/III a 1).

- Mannerstråle, Carl-Filip, Nya huset i Andrarum Anno 1741, Piperska Handlingar No. 1, Christinehof 1991.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE