ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

DISAGREEMENTS AND UNPLEASANTNESS

– Textile Observations during 18th Century Natural History Travels

‘Having set out on his journey and as though transported into a new world, he should consider it incumbent upon him to observe everything…’ This advice was part of Carl Linnaeus’ printed dissertation Instruction for Naturalists on Voyages of Exploration in 1759, which gave a multitude of recommendations for long journeys over land and sea. It was desired to avoid all sorts of disputes and disagreements, but this was, of course, not always realised. It seems to have been quite unusual to describe textile materials, dyes, footwear and clothing as unpleasant, unpractical, disagreeable, ugly or unattractive judging by their journals and correspondence. This essay will give a glimpse into such everyday observations – made by five former students of Linnaeus – experienced from a European perspective on long-distance voyages.

Carl Peter Thunberg who travelled for nine years during the 1770s in Europe, Africa and Asia, complained no more than the other seventeen Apostles of Linnaeus, but in his journal from Batavia (Jakarta) in May 1775 Thunberg wrote: ‘Although the heat, as appears from Fahrenheit’s thermometer, which generally stands between eighty and eighty-six degrees, is not so very intense, it is nevertheless exceedingly troublesome and disagreeable; first, from the situation of the town which lies low near the waterside, and then, in consequence of the exhalations from the sea and bogs stagnating in the air, and from their being little or no wind to disperse these vapours and purify the atmosphere ...’ Such circumstances are reflected in this somewhat earlier copperplate (1744-46), from ‘The Tygers street canal in Batavia’ where the buildings are located close to the river and many of the pictured individuals appear to be dressed or wrapped in thin fabrics. (Courtesy of: Wellcome images L0038152).

Carl Peter Thunberg who travelled for nine years during the 1770s in Europe, Africa and Asia, complained no more than the other seventeen Apostles of Linnaeus, but in his journal from Batavia (Jakarta) in May 1775 Thunberg wrote: ‘Although the heat, as appears from Fahrenheit’s thermometer, which generally stands between eighty and eighty-six degrees, is not so very intense, it is nevertheless exceedingly troublesome and disagreeable; first, from the situation of the town which lies low near the waterside, and then, in consequence of the exhalations from the sea and bogs stagnating in the air, and from their being little or no wind to disperse these vapours and purify the atmosphere ...’ Such circumstances are reflected in this somewhat earlier copperplate (1744-46), from ‘The Tygers street canal in Batavia’ where the buildings are located close to the river and many of the pictured individuals appear to be dressed or wrapped in thin fabrics. (Courtesy of: Wellcome images L0038152).The naturalist Peter Forsskål instead took part in The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia (1761-63); he experienced many general problems and sadly died of possible malaria in Yemen in July 1763, just 30 years old. In the previous year for instance, in October 1762, the journey had continued via South Arabia, where his botanical collections became considerable – including plants for natural dyes – often assisted by local inhabitants, but he also mentioned on several occasions the troubles and dangers of moving around in the area due to the suspicious nature of local groups. The dilemma was not only having to take account of the problems of being accepted as a European; there had from the very beginning also been disagreement between members of the expedition.

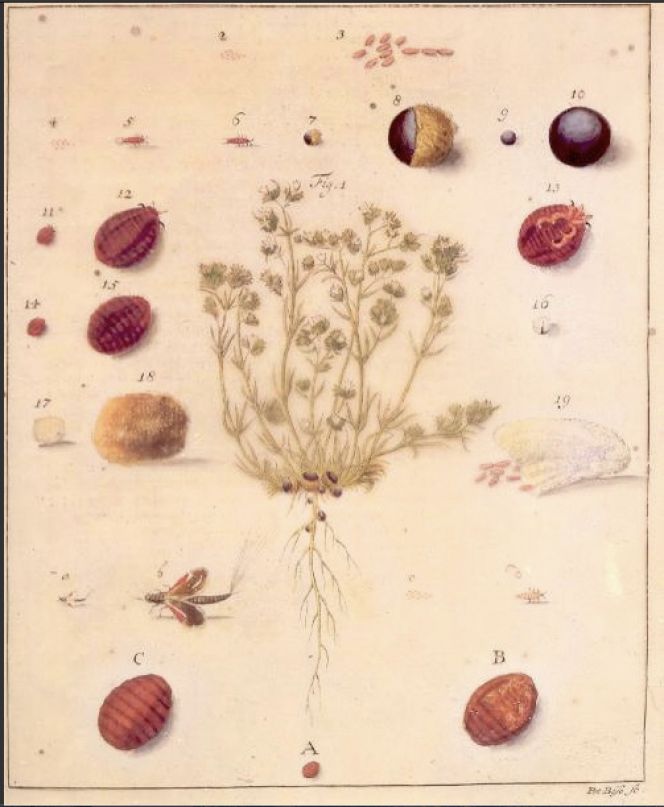

Another former student of Linnaeus, Johan Peter Falck was one the leaders for the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Natural History Expeditions from 1768 to 1774. Among many matters concerning textile dyeing, he noted that Polish cochineal was seen to be a poor choice by some dyers. His extensive journal included information about that this dye worked best on wool as the professional silk-dyers in Moscow complained Polish cochineal gave the silk a poor and unattractive colour, which might give the professional dyers a bad reputation. In the Bukharan dye-works Polish cochineal (also named kermes) was often used, but whenever possible the genuine cochineal was preferred. That was chiefly bought from the merchants of Orenburg. (Image from: Breyn, Johann Philip, Historia naturalis Cocci Radicum Tincttorii quod Polonicum…1731, Wikimedia Commons).

Another former student of Linnaeus, Johan Peter Falck was one the leaders for the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Natural History Expeditions from 1768 to 1774. Among many matters concerning textile dyeing, he noted that Polish cochineal was seen to be a poor choice by some dyers. His extensive journal included information about that this dye worked best on wool as the professional silk-dyers in Moscow complained Polish cochineal gave the silk a poor and unattractive colour, which might give the professional dyers a bad reputation. In the Bukharan dye-works Polish cochineal (also named kermes) was often used, but whenever possible the genuine cochineal was preferred. That was chiefly bought from the merchants of Orenburg. (Image from: Breyn, Johann Philip, Historia naturalis Cocci Radicum Tincttorii quod Polonicum…1731, Wikimedia Commons).The arrival and the early days in Suriname were particularly difficult for Linnaeus’ apostle Daniel Rolander: a combination of heat, humidity, strong smells, insects’ buzzing, “dangerous animals”, and a general feeling of uneasiness. Sleeping and getting some night rest was also extremely trying, at the same time as he had to get used to sleeping in a hammock woven of cotton. Yet that berth was thought considerably more comfortable in the constant heat than a warm bed. The hammock could also have the advantage of making it more difficult for crawling insects to surprise the sleeper, though it was no guarantee as they might drop down from the ceiling, which is mentioned on 26 June 1755. ‘About midnight, a short time before I had gone to sleep, I felt a small animal moving on my foot. I immediately grabbed a lit candle, and having carefully and gradually withdrawn the hammock from my foot, I discovered a Scorpio Americanus slowly moving across my foot. My hair stood on end, and my limbs turned to ice, but nevertheless, I kept my foot still until this unpleasant insect had gone past it and into the hammock.’ Rolander escaped unscathed from the incident and continued to sleep in the cotton hammock. He also noted the significance of that sleeping arrangement in other contexts, mainly to do with what materials were used and who manufactured them.

![Lepisma saccharina [argentea], commonly named silverfish, was the tiny insect of about 1cm in length, which caused Daniel Rolander much trouble on his sea voyage to and fro Suriname. To look-out for the insect was undoubtedly important during long periods at sea, as it thrives in damp conditions. The silverfish easily finds its way into every nook and cranny and can cause a great deal of damage as it chooses to attack clothes, books, paper and everything else that a travelling apostle carried in his baggage. (Lepisma saccharina, Wikimedia Commons).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/3-rolander-800x296.jpg) Lepisma saccharina [argentea], commonly named silverfish, was the tiny insect of about 1cm in length, which caused Daniel Rolander much trouble on his sea voyage to and fro Suriname. To look-out for the insect was undoubtedly important during long periods at sea, as it thrives in damp conditions. The silverfish easily finds its way into every nook and cranny and can cause a great deal of damage as it chooses to attack clothes, books, paper and everything else that a travelling apostle carried in his baggage. (Lepisma saccharina, Wikimedia Commons).

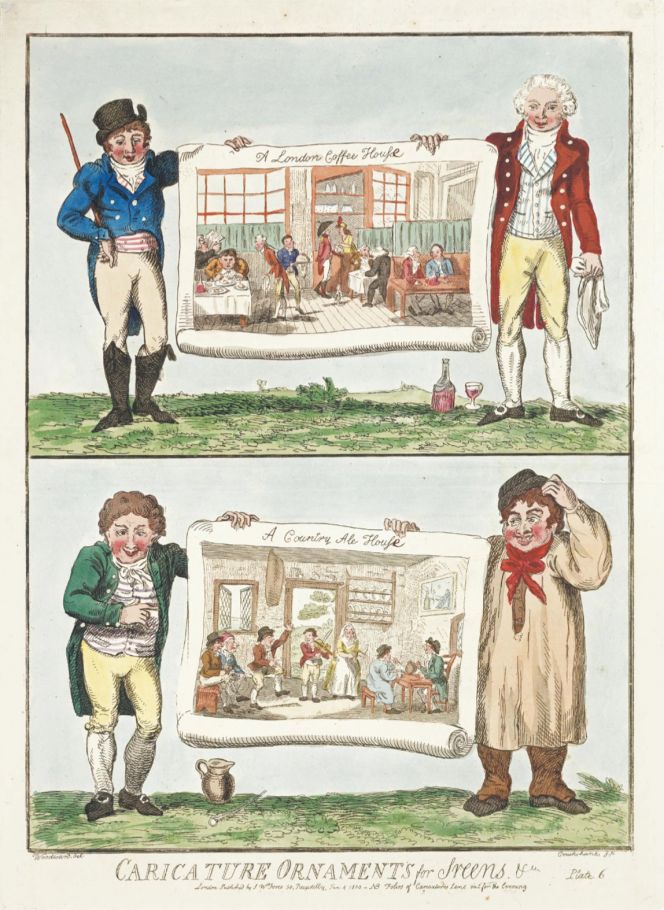

Lepisma saccharina [argentea], commonly named silverfish, was the tiny insect of about 1cm in length, which caused Daniel Rolander much trouble on his sea voyage to and fro Suriname. To look-out for the insect was undoubtedly important during long periods at sea, as it thrives in damp conditions. The silverfish easily finds its way into every nook and cranny and can cause a great deal of damage as it chooses to attack clothes, books, paper and everything else that a travelling apostle carried in his baggage. (Lepisma saccharina, Wikimedia Commons). The naturalist Pehr Kalm described various issues with his shoes and boots in the North American travel journal as well as in his expenses account from the same journey, lasting 1747 to 1751. He travelled from Göteborg in Sweden, via the Norwegian coastal towns, had a circa six months stay in London and surrounding counties before crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the North American colonies, which was his main destination. Even if appearing in print 50 years later, this caricature of ‘The Metropolitan Coffee House’ in London by Isaac Cruikshank gives a detail view of shoes with silver buckles and leather boots (top image), probably very similar in style to Kalm’s used footwear. (Courtesy of: The Lewis Walpole Library/Yale University Library, Farmington, US).

The naturalist Pehr Kalm described various issues with his shoes and boots in the North American travel journal as well as in his expenses account from the same journey, lasting 1747 to 1751. He travelled from Göteborg in Sweden, via the Norwegian coastal towns, had a circa six months stay in London and surrounding counties before crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the North American colonies, which was his main destination. Even if appearing in print 50 years later, this caricature of ‘The Metropolitan Coffee House’ in London by Isaac Cruikshank gives a detail view of shoes with silver buckles and leather boots (top image), probably very similar in style to Kalm’s used footwear. (Courtesy of: The Lewis Walpole Library/Yale University Library, Farmington, US).

Already during Kalm’s time in London, he prepared for the dangers of rattlesnakes in North America, for instance, and wrote on 4 May 1748 in his travel journal: ‘If one is wearing boots one has nothing to fear from it, as it is unable to bite through the boot.’ On 15 June 1749, he lingered on the same subject that it was practical and safe to wear boots, in this case, due to the immense swarm of gnats in the vast woods and uninhabited grounds between Albany and Canada, but the problem was that it is being too hot to be comfortable in leather boots. Whilst the wear and tear of shoes even was an extensive issue not only when travelling or collecting natural history specimens in the countryside, but also in the city of Quebec itself: ‘The streets in the upper city have a sufficient breadth, but are very rugged, on account of the rock on which it lies; and this renders them very disagreeable and troublesome, both to foot-passengers and carriages. The black lime slates basset out and project everywhere into sharp angles, which cut the shoes in pieces’ (5 August 1749).

Even if negative experiences linked to clothing, shoes, textile materials and other similar observations can be traced to these 18th century long-distance travelling naturalists. The overall impression is that they quite seldom revealed emotions of boredom, discontent, annoyance, apathy, unconcern or frustration regarding their work and everyday life in their writings. Probably due to that, their instructions gave advice of “positive thinking” – that is to say, it was desired to observe everything useful, be curious as well as diligent to be able to add new-learned knowledge to one’s travel diary on a daily or at least a regular basis.

Sources:

- Breyn, Johann Philip, Historia naturalis Cocci Radicum Tincttorii quod Polonicum…1731.

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & Vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Kalm, Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland, Helsingfors 1956.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, 8 volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012. (Quote & facts: Instruction for Naturalists on Voyages of Exploration, in Volume One, pp. 201-211. & Volume Three: Pehr Kalm’s & Daniel Rolander’s journals).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 70, 78, 155, 163, 218 & 263).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE