ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

DOMESTIC & IMPORTED WOOLLEN CLOTH

– a Medieval Town

This fourth historical essay on the Malmö area’s textile trades and material culture is the first of several texts describing the new circumstances for the coastal Medieval town. Various trades had by now been of importance for a long time, but the growing population gave it new dimensions. For textiles and clothing, this is evident through hundreds of preserved textile fragments – mainly from the 14th and 15th centuries – many of these are believed to have been imported via the Hanseatic trade. Woollen pieces of cloth dominate, but silk and linen are also well represented, together with a substantial number of textile tools. Here, we will look more closely into the domestic and imported woollen cloths, their colours and also how wool was used for textile techniques other than weaving.

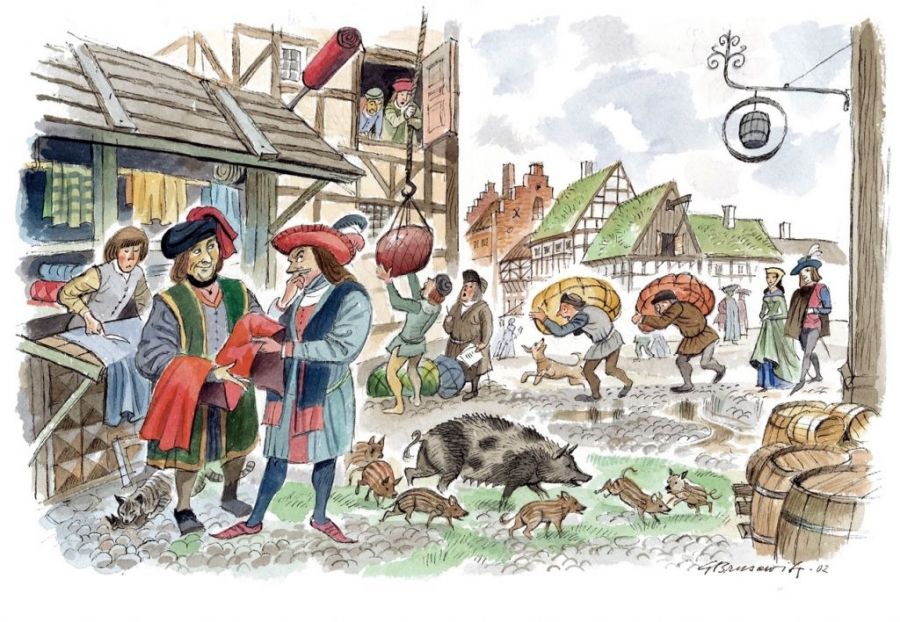

A lovely artistic impression of how the coastal town Malmö, its cloth trade and daily life could have appeared in late Medieval time. Illustration: Gunnar Brusewitz in 2000.

A lovely artistic impression of how the coastal town Malmö, its cloth trade and daily life could have appeared in late Medieval time. Illustration: Gunnar Brusewitz in 2000.The cloth trade had its centre around Adelgatan, a street including the so-called Høje klædebother [Høje’s cloth shops], which sold fine imported quality woollen broadcloth as well as coarser domestically woven wadmal types. The historian Sven T. Kjellberg emphasised that a document from the 1430s proves that “cloth shops” at this location had permanent positions and lively commerce. Even earlier, Valdemar Atterdag (Danish King 1340-75) also included information about this cloth trading in a charter from 23rd December in 1360. The imported woollen cloth primarily came to Malmö via Lübeck and other Hanseatic towns.

Medieval depictions/texts also give clues as to how cloth was packed in large bales when transported and loaded on and off the cogs. The regulations for this trade meant that each piece of cloth must be 44 ells long or, as a half-piece, 22 ells (one ell = c. 59-63cm). To demonstrate the qualities of these fabrics, each parcel or bale was emblemed with a lead cloth seal (see below), showing the origin of the traded goods. These seals have been found in smaller numbers during excavations in Malmö, with origins from Leyden, Göttingen and other places. However, archaeological textile fragments found in Malmö can not be pinpointed to one particular location, nor the domestically made nor imported fabrics. On the other hand, it is known that the town had a cutter’s [wantsnidare] regulation via a charter by Eric of Pomerania (Danish King 1396–1439) dating 5th May in 1415. These men are believed to have been involved in the selling of cloth as well as the cutting of cloth for the tailors.

Even if some of the broadcloth is believed to have been locally produced, the finest qualities were probably imported from Flanders. These were often called “sheets” [lakan], yet there also existed various special names depending on when and where the fabrics were made. For example: Panni gandauensis in 1286 from Gent in Flanders, lybist grath in 1329 from Lübeck and kolsester in 1467 woven in Colchester in England. Fine broadcloth of similar imported origins have been found in excavations in Malmö, but the coarser wadmal occurred in much greater numbers.

These textile fragments have primarily been excavated from Medieval earth closets in one of the town’s older districts – St Gertrud. Two of many samples are of a fine twill woven broadcloth in brownish wool: 17 threads/cm in the warp and 19 threads/cm for the weft (4560:3:9&11). A somewhat coarser broadcloth quality – 13/14 threads/cm – has additionally been found, for example, a plain woven reddish-brown fragment (4560:2:22). These broadcloths are believed to have been worn by local burgers or merchants, whose woollen clothing originally was red in colour among other hues.

From my knowledge, no chemical analyses on individual fragments from the area have been done to establish which exact dyestuff was once in use. The finer imported broadcloths can, for example, have been dyed with the expensive scale insect kermes. Still, it is more likely that the majority of reds were dyed with roots of madder or some suitable Galium species (see images below). The madder could have been grown in sheltered positions in Malmö gardens or imported via southerly trade. None of the woollen fragments have traces of blue colour, but some are yellowish-brown (4560:3:11). Without doubt, many fabrics must have been yellow, while this, even since earlier periods, is proved to have been the easiest and most common way to get some type of colour on your garment. Local plants gave numerous possibilities, but from the dictionary Kulturhistoriskt Lexikon för Nordisk Medeltid, one can read that dyer’s weed (Reseda luteola) and bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) were the most used dyes for yellow during the Medieval time in the Nordic area.

![In this somewhat later Herbal by John Gerard, Red madder or Rubia tinctorum [tinctoria] is primarily described from a medicinal point of view. But the skilfully drawn plant gives a good impression of the fleshy root, used for its unsurpassable qualities for dyeing red shades on yarn and cloth (Gerard, 1633/1597, pp. 1118-21).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/3-medieval-cloth-664x1150.jpg) In this somewhat later Herbal by John Gerard, Red madder or Rubia tinctorum [tinctoria] is primarily described from a medicinal point of view. But the skilfully drawn plant gives a good impression of the fleshy root, used for its unsurpassable qualities for dyeing red shades on yarn and cloth (Gerard, 1633/1597, pp. 1118-21).

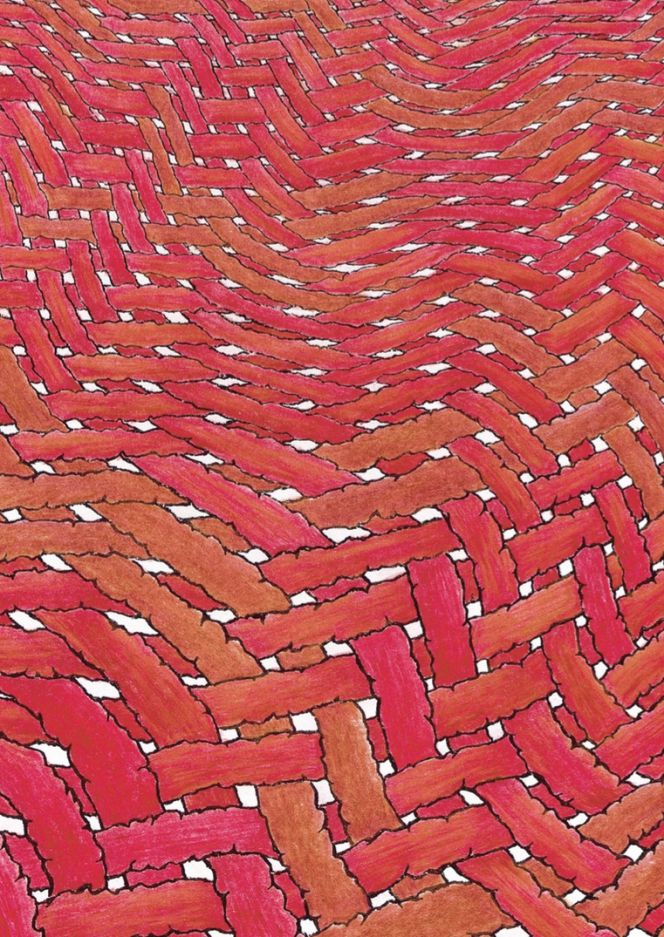

In this somewhat later Herbal by John Gerard, Red madder or Rubia tinctorum [tinctoria] is primarily described from a medicinal point of view. But the skilfully drawn plant gives a good impression of the fleshy root, used for its unsurpassable qualities for dyeing red shades on yarn and cloth (Gerard, 1633/1597, pp. 1118-21). The roots of madder and a few Galium species were the most common sources for dyeing red colours of various shades during both the Viking age and Medieval time in northern Europe, based on knowledge primarily learned from excavated textile fragments. This illustration aims to give a close-up impression of a madder dyed twill woven fabric. (Illustration: Helen Hodgson).

The roots of madder and a few Galium species were the most common sources for dyeing red colours of various shades during both the Viking age and Medieval time in northern Europe, based on knowledge primarily learned from excavated textile fragments. This illustration aims to give a close-up impression of a madder dyed twill woven fabric. (Illustration: Helen Hodgson). Even if there are no traces of blue fabrics or fragments from Medieval Malmö, it is highly likely that woad (Isatis tinctoria) was in use for dyeing blue. This dye-plant could either be locally grown or imported. A statue “Woad Merchants” from the Amiens Cathedral in France is one interesting comparable source demonstrating that this important dye-stuff for the colour blue in Europe during this period could be sold via merchants trading in woad. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images).

Even if there are no traces of blue fabrics or fragments from Medieval Malmö, it is highly likely that woad (Isatis tinctoria) was in use for dyeing blue. This dye-plant could either be locally grown or imported. A statue “Woad Merchants” from the Amiens Cathedral in France is one interesting comparable source demonstrating that this important dye-stuff for the colour blue in Europe during this period could be sold via merchants trading in woad. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images).The coarser wadmal cloth (c. 7-10 threads/cm) in both twill and plain weave has been the most frequent textile finds in archaeological excavations in Malmö. These fabrics are believed to originate from domestic produce, which could be traded at local markets or bartering for other goods. Excavations have also unearthed two pieces of wool and three fragments of woollen yarn. Just like the woven fabric, the wool in itself was a trading commodity, but historians have come to the conclusion that it was much more common to sell and buy the woven wadmal when it was a much more valuable produce than the wool itself. Needle binding for socks and mittens was another use for wool, even if no actual fragments have been found in Malmö. On the other hand, the needle binding technique was common in the Nordic countries during the Iron Age, and the geographically closest find of this technique has been excavated in nearby Lund in the form of a woollen mitten.

Notice: The numbering within brackets is Malmö Museum’s catalogue numbers. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of excavated textile fragments, tools, etc, please see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen, 2001.

Sources:

- Gerard, John, Herbal or General Historie of Plantes, 1633 (First published 1597).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Förhistoriska och Medeltida Textilier i Malmö’, Elbogen pp. 73-144, 2001 (pp. 103-10).

- Kjellberg, Sven T., Ull och Ylle, Lund 1943.

- Kulturhistoriskt Lexikon för Nordisk medeltid, band 1-22, 1982.

- Wellcome Images, digital source (‘Statues at Amiens Cathedral, Woad merchants’).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE