ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

DYEING WITH LICHENS

– Traditions, Experiments and Books: 1740s to 1810s

The physician and naturalist Johan Peter Westring had an interest in natural dyeing. From a historical perspective, he foremost followed in the footsteps of his former teacher Carl Linnaeus and female dyers in farming communities in Sweden. Dyeing with lichens and mosses had lengthy traditions, which Westring aimed to promote further, even if his idea to replace expensive imports with native species to benefit the economy of his home country, in many ways was not realised. In his outstanding book however, 24 lichens are meticulously described, including a great number of recipes for each plant. The variations in colour could be considerable between the individual lichens, depending on the kind of material for which they were used; the choice of mordant; the time of the year when the lichen was picked and how it was treated. The book contains beautiful hand-coloured illustrations of the lichens and the colours they could yield, according to the writer, primarily in yellow-brown, yellow-green and reddish. A unique yarn sample collection by his hand has also survived, which gives additional insight to his work with natural dyes.

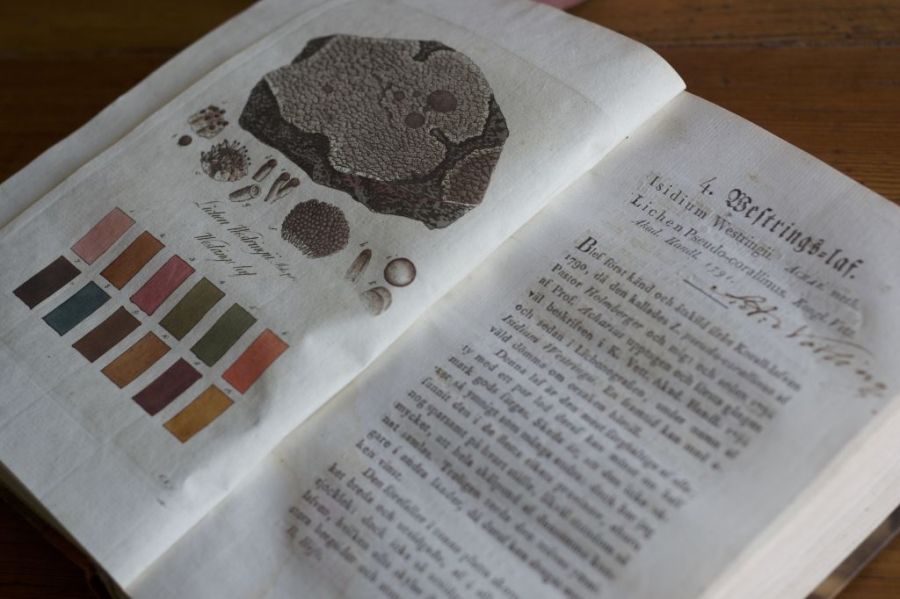

An interest in the potential of lichens for generating colour was noticed by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) on several occasions. The usefulness of lichens for plant dyeing was given an upswing in the latter half of the 18th century through books on the subject. The literature was then becoming more specialised and in France for example, was published in 1787 ‘Mémoires sur l’útilité des Lichens, dans la médecine et dans les arts’. This French book makes frequent references to Linnaeus and to his knowledge on the subject of dyeing. The publication ends with beautifully coloured plates of the result of dyeing with lichens; browns, greys, yellows and russets predominating. Equivalent in aims to Johan Peter Westring’s (1753-1833) ‘Svenska lafvarnas Färghistoria…’ (The Dye History of the Swedish Lichens…) in 1805, which is the focus of the essay. The book particularly stands out due to its beautiful and accurate plates after an original by the botanist and physician Erik Acharius (1757-1819) and the draftsman and engraver Johan Wilhelm Palmstruch (1770-1811). It is worth noting that the two men mentioned first, Westring and Acharius, were students of Linnaeus in his later years. | Illustrated here is ‘4. Westrings-laf’ (Westring’s lichen) named after himself. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

An interest in the potential of lichens for generating colour was noticed by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) on several occasions. The usefulness of lichens for plant dyeing was given an upswing in the latter half of the 18th century through books on the subject. The literature was then becoming more specialised and in France for example, was published in 1787 ‘Mémoires sur l’útilité des Lichens, dans la médecine et dans les arts’. This French book makes frequent references to Linnaeus and to his knowledge on the subject of dyeing. The publication ends with beautifully coloured plates of the result of dyeing with lichens; browns, greys, yellows and russets predominating. Equivalent in aims to Johan Peter Westring’s (1753-1833) ‘Svenska lafvarnas Färghistoria…’ (The Dye History of the Swedish Lichens…) in 1805, which is the focus of the essay. The book particularly stands out due to its beautiful and accurate plates after an original by the botanist and physician Erik Acharius (1757-1819) and the draftsman and engraver Johan Wilhelm Palmstruch (1770-1811). It is worth noting that the two men mentioned first, Westring and Acharius, were students of Linnaeus in his later years. | Illustrated here is ‘4. Westrings-laf’ (Westring’s lichen) named after himself. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.Whether dyeing with lichen increased in practice to any significant extent in the Swedish provinces after Westring’s publication in 1805 is doubtful, though. According to his first essay on the subject in Kungliga Vetenskaps Akademiens Handlingar (the Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences) in 1791, he wrote: ‘It is generally known that Lichen (Moss) can dye woollens. The country people in particular know 4 to 6 species for this use…’ (p. 115). A practice, which Carl Linnaeus among others also reflected over and exemplified during provincial tours in the 1740s. However, due to the complexity of Westring’s receipts, knowledge amassed in a book like his clearly also had limited chances to reach female dyers in farming communities, as well as that rules and regulations for professional dyers restricted such innovations. Reasons, which together made it unlikely that his recommendations of that native lichens had the potential to be replacements for well established imported natural dyes. His thoughts in the same essay additionally point at a wishful thinking that dye lichens could give a substantial trading profit if exported, substituting the present import of costly plants. He noted: ’Orchil, Parelle d’Auvergne and Roccelle are prepared from lichen species, and the foreigner earn much from these dyestuffs’ (p. 114).

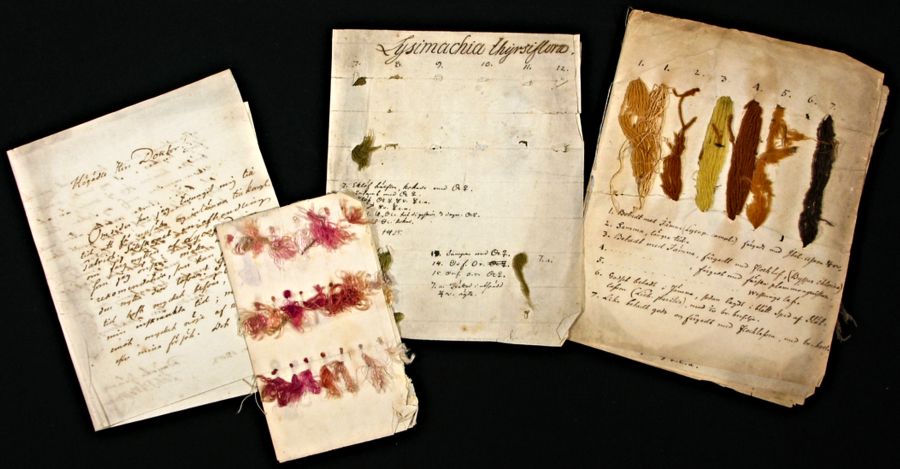

This natural dye sample collection with lichens and mosses by Johan Peter Westring (and assistants), was produced 1791-1803 – includes preparatory work for his book, published in 1805. The yarn samples of silk and wool, demonstrates his longterm dedication and hands on work with dyeing experiments. According to research by the Nordic Museum, this unique four-part collection of dye samples consists of: A. 4 silk and 25 wool samples (originally a total of 29 samples). B. Four samples (originally 11 samples). C. A letter dated Norrköping 23 January in 1803 by Westring to unknown addressee. D. 63 silk samples, mainly in light purple and pink shades. | Production by Johan Peter Westring et al, in Norrköping, Sweden. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0405402A-D. Digitalt Museum).

This natural dye sample collection with lichens and mosses by Johan Peter Westring (and assistants), was produced 1791-1803 – includes preparatory work for his book, published in 1805. The yarn samples of silk and wool, demonstrates his longterm dedication and hands on work with dyeing experiments. According to research by the Nordic Museum, this unique four-part collection of dye samples consists of: A. 4 silk and 25 wool samples (originally a total of 29 samples). B. Four samples (originally 11 samples). C. A letter dated Norrköping 23 January in 1803 by Westring to unknown addressee. D. 63 silk samples, mainly in light purple and pink shades. | Production by Johan Peter Westring et al, in Norrköping, Sweden. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0405402A-D. Digitalt Museum).Overall, in his study of dyeing in 1805, the physician Johan Peter Westring used 1/2 pound (ca 210 g) of dye-lichen in proportion to 1 mark (ca 420 g) woollen yarn. Westrings-laf (Westring’s lichen), for example. With that, it was possible to yield a beautiful greenish colour (merde d’oie) on wool and silk. He noted:

- ‘To two lod [ca 27 g] of lichen add common salt, saltpetre and purified potash, 1/2 quintin [ca 1.5 g] of each, and add one stoop [a quarter of a gallon] of water or a little more and put in a warm place to macerate for a couple of days; only after that is the goods placed in it, when after 2-3 hours it will first be dyed orange, but after 16 or 20 it obtains the promised colour, which is very fast and strong…’

In complete accordance with Linnaeus’ observations about 60 years earlier, the physician also regarded the dye-lichen (Plate 2. Färg-laf) as of extreme significance for dyeing red and also brown. Westring demonstrated it by trying out 30 different recipes on that particular lichen, with appropriate illustrations and colour samples. One form of lichen that he did not mention, however, was the Viking dye-moss (although not by that name), which Linnaeus noted in his journal on his way to Öland on 27 May 1745. The Viking dye-moss was commonly known as byttelet; and from Småland we are told that it was bought from the people of Västergötland and ‘…looks like a dark clay with many red blotches interspersed…’ That statement was confirmed in his journal from the Västergötland Journey of 12 July 1746 in the meticulous description of the Viking dye-moss and Linnaeus’ particular surprise that it was unknown abroad:

- ‘Byttelet is a red dye which the people of Västergötland sell all over the country, of which I was never able through enquiries to get any sensible account, although the dye was known all over Sweden. I was told that the people of Västergötland from the Borås area annually travel here to the rocks by the sea, but especially to Hissingen, which on the north side faced this way, where they collect a moss of which they eventually produce their byttelet…Hereof follows that the byttelet remains the very same which had been described by Mr Kalm…’

Pehr Kalm’s (1716-1779) account from Bohuslän of 27 July 1742 is comprehensive on the subject too of what kind of white rock lichens which agrees well with byttelet. The Viking dye-moss and other lichens gave the poorer section of the population access to a reliable red dye. That assumption is further reinforced by the fact that urine was used as a mordant, which had the added advantage of being free of charge. It is noticeable that Kalm was one of Linnaeus’ earlier students, about 30 years prior to Westring’s study years.

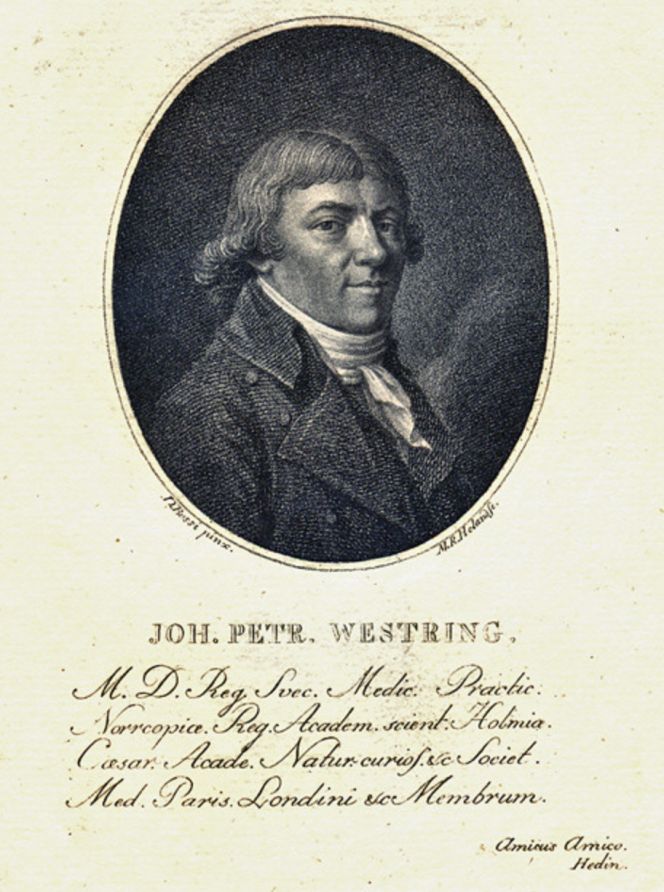

Etching of Johan Peter Westring, probably dating to the mid-1790s, when he was about 40-years-old. In particular evident via the Latin text, which informs about his profession as a Royal physician (which he became in 1794), his medical practice in Norrköping as well as memberships of learned societies in London and Paris. That is also to say, during the same time in his life as he made experiments with dyeing of lichens, published his observations in Kungliga Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar (Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences) and planned for his future publication about natural dyeing of wool, silk, linen and cotton with native growing species in Sweden. (Private Collection: Single etching of Joh. Petr. Westring).

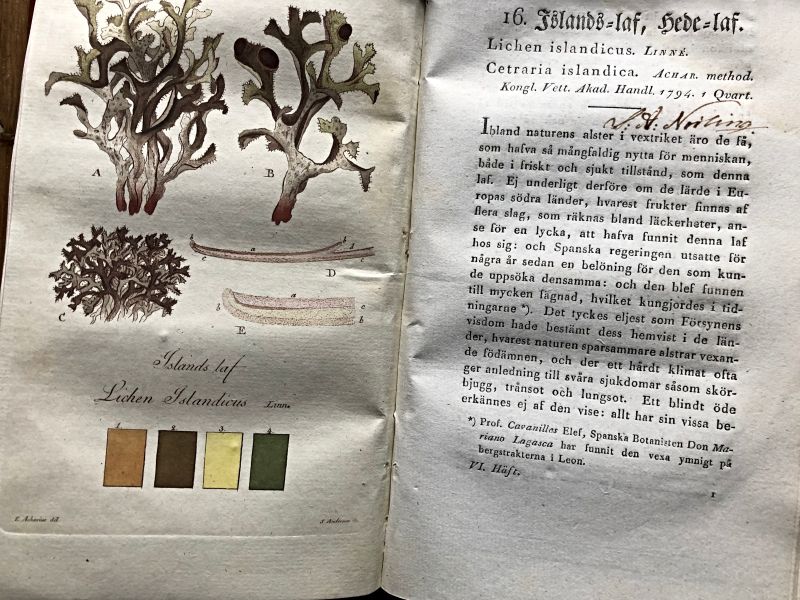

Etching of Johan Peter Westring, probably dating to the mid-1790s, when he was about 40-years-old. In particular evident via the Latin text, which informs about his profession as a Royal physician (which he became in 1794), his medical practice in Norrköping as well as memberships of learned societies in London and Paris. That is also to say, during the same time in his life as he made experiments with dyeing of lichens, published his observations in Kungliga Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar (Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences) and planned for his future publication about natural dyeing of wool, silk, linen and cotton with native growing species in Sweden. (Private Collection: Single etching of Joh. Petr. Westring).To brown and yellow shades, there were many suggestions in Westring’s book; the Iceland moss (Islands-laf) for instance, could yield a ‘Light brown colour on wool and a beautiful sulphurous yellow…colour on silk. ‘When the lichen is put with 2 lod [ca 27g] quicklime, 1 1/2 lod [ca 20g] sugar of lead, and 8 lod [ca 108 g] sumach, to each mark [1 mark, ca 420 g] of lichen and goods, and kept in an even warm maceration for 2 or 3 days, thus those colours will be achieved.’

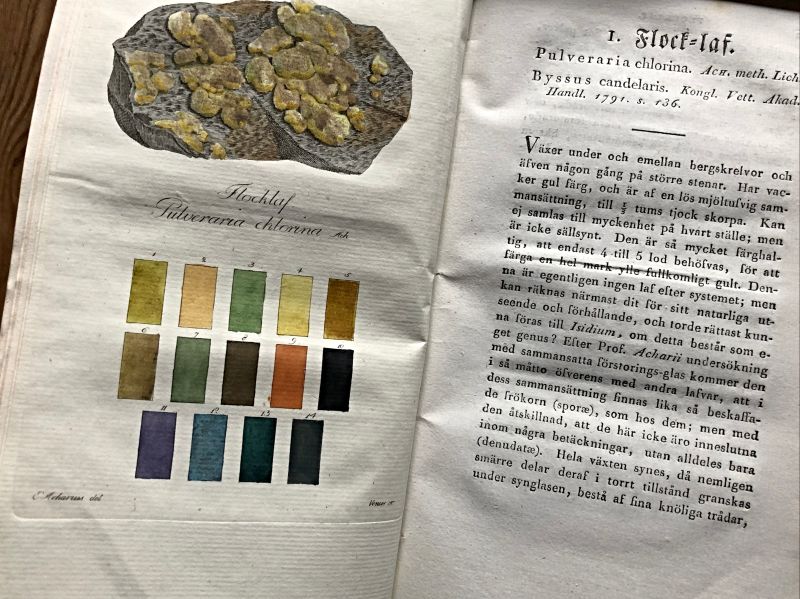

Using the combination of quicklime, sugar of lead and sumach was otherwise a typical method of Westring’s for producing nuances of brown, also when using other lichens. In the same way sour small beer, old urine, common salt and pure potash were often recommended as means of obtaining the best colours. Although doubts as to the fastness and nuance of the colours may occasionally arise when one reads the recipes, there is however no mistaking Westring’s deep commitment to the potential of dyeing with lichen. During the whole of the 1790s and until the publication of the book, Westring made his results known in Kungliga Vetenskaps Akademiens Handlingar (the Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences) of which he was a member, in a painstakingly meticulous manner. Five of the hand-coloured plates from the book are illustrated below – without analysis – as the beauty of the plates aims to be the focus. Simultaneously to emphasise the great effort, interest, cooperation with artists, attention to detail and the dedication as he put into this publication. With a substantial number of experiments for each description. It is noticeable too, that imported indigo was repeatedly included as one of the dyestuffs in combination with various lichen species, when he tried to achieve true blue colours. Local, national and global influences were intertwined, even if the main dyes, the lichen were native species in Sweden.

Plate 1. ‘Flock-laf’ (mustard powder lichen), with seventeen receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

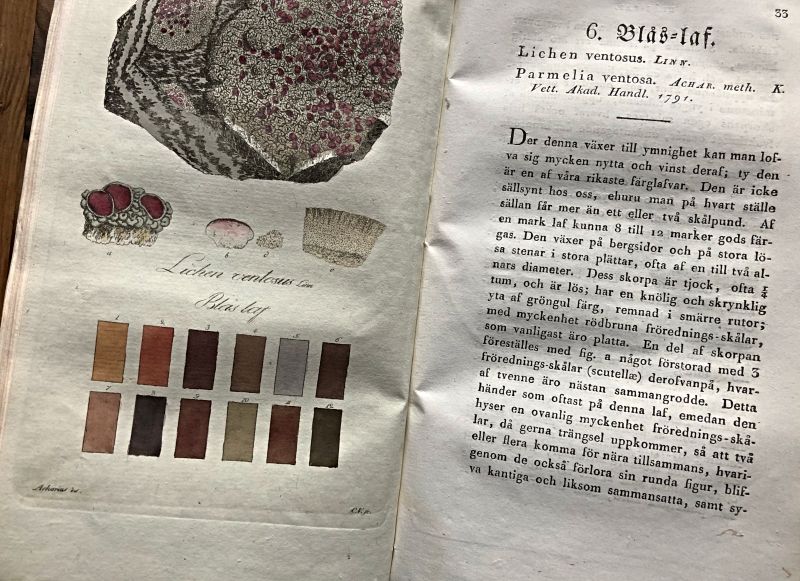

Plate 1. ‘Flock-laf’ (mustard powder lichen), with seventeen receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation. Plate 6. ‘Blås-laf’ (lichen of the family Ophioparmaceae), with 37 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

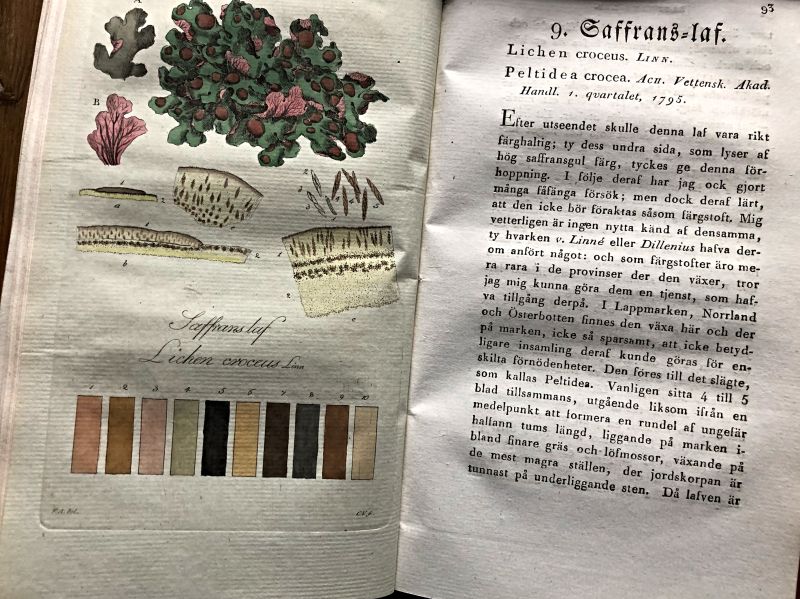

Plate 6. ‘Blås-laf’ (lichen of the family Ophioparmaceae), with 37 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation. Plate 9. ‘Saffrans-laf’ (saffron lichen), with 28 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

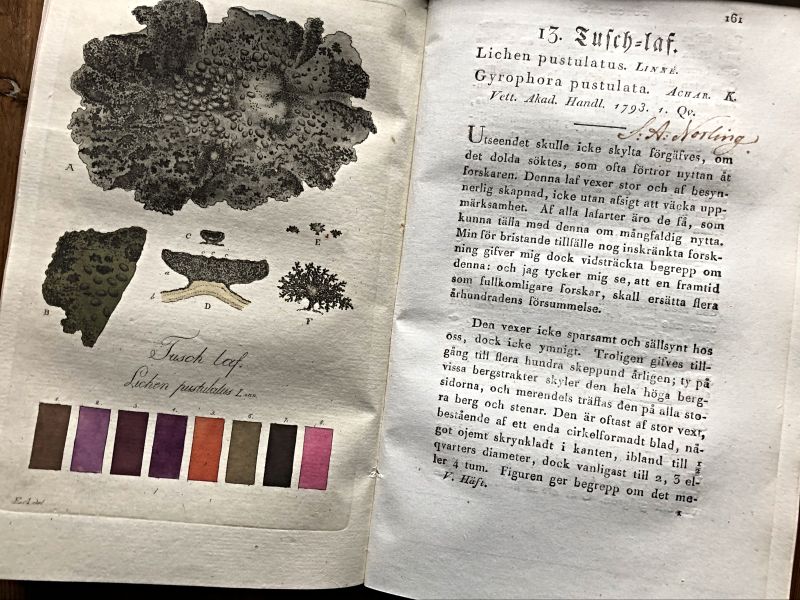

Plate 9. ‘Saffrans-laf’ (saffron lichen), with 28 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation. Plate 13, ‘Tusch-laf’ (Ink lichen), with 30 receipts for wool and silk, added with instructions to make ink. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

Plate 13, ‘Tusch-laf’ (Ink lichen), with 30 receipts for wool and silk, added with instructions to make ink. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation. Plate 16, ‘Islands-laf’ (Iceland moss), with 20 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.

Plate 16, ‘Islands-laf’ (Iceland moss), with 20 receipts for wool and silk. (From: Westring, Joh. P…1805). Private Collection. Photo: The IK Foundation.The general idea over the 18th century was also to the encourage the development potential for the country’s mercantile economy, which for instance included to make use of as many native species as possible for dyeing of yarn and cloth, which was regarded to improve conditions for the country as well as for its inhabitants. However, from the perspective of professional dyers at the time, the mercantile idea of self-sufficiency in dyes was partly contradictory, given their strict regulatory system. They preferred durable imported dyes like indigo, woad and madder to the obtain the desirable blue, green and red colours, but to some extent this obstructed the introduction of “new” native dye-plants, while at the same time that was the wish of the State. The textile manufacturer Jonas Alström’s (1685-1761) storehouses came to be particularly well documented by Carl Linnaeus during his provincial tour to in 1746. In his journal on 7 July, he noted a wide selection of imported dyes, such as:

- ‘Brazil-wood, sappan, Pernambuco, yellow-wood, campeachy wood, wood from Versecz, Japanese wood, weld (French and Swedish), orchil [a lichen], litmus, woad (English, French, [Thuringian] from Erfurt, Swedish; the two latter equally good and the best), indigo, common madder, sumach, pomegranate peel, laurel berries, oak-apple, cochineal, acorns from a certain species of oak and Spanish pepper’.

The dependence of durable dyes via long-lasting trade routes and imports were deeply rooted traditions, often stretching centuries back in time, and seen as necessary goods from the dye manufacturers’ angle. Among other reasons, they often had to obtain exact nuances after their customers’ wishes and preferably dye truly durable colours. Just as fashionable cosmopolitan influences overall were hard to restrict in Sweden despite all rules and complex regulations. When it concerned import of dyes from the mid-18th century and over the next one hundred years – cochineal red became the most popular, which gave “new” striking and fashionable shades of scarlet red, purple and pink.

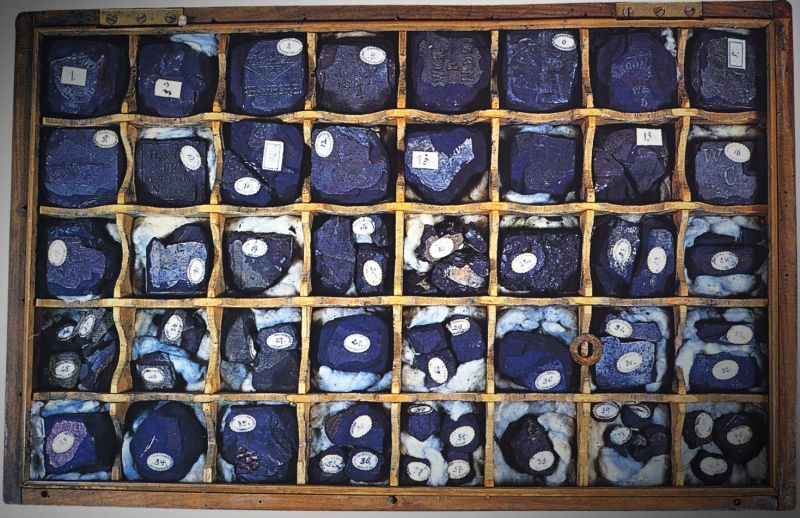

Sample box of indigo, imported from Guatemala, Java and India by S. Schönlank, Berlin 1756. This unique sample collection of indigo demonstrates the multitudinous and specialised nature of that sought-after commodity for the dye-works in Europe. It is also noticeable, that even if Johan Peter Westring promoted the use of lichen for natural dyes in Sweden, imported indigo was needed in the several receipts for green and blue colours. In such cases, he recommended to use ‘the best sort of indigo’. (Courtesy: Deutsches Textilmuseum, Krefeld, Germany no. 16044).

Sample box of indigo, imported from Guatemala, Java and India by S. Schönlank, Berlin 1756. This unique sample collection of indigo demonstrates the multitudinous and specialised nature of that sought-after commodity for the dye-works in Europe. It is also noticeable, that even if Johan Peter Westring promoted the use of lichen for natural dyes in Sweden, imported indigo was needed in the several receipts for green and blue colours. In such cases, he recommended to use ‘the best sort of indigo’. (Courtesy: Deutsches Textilmuseum, Krefeld, Germany no. 16044). A few concluding reflections of natural dyeing in Sweden.

Just as in the case of other literature on the subject, the readership was limited, although the people with a basic ability to read were relatively numerous in Sweden in the 18th- and early 19th century, yet most of the amateur dyers simply could not afford to buy books. Whilst, as late as the 1870s, many of the old methods still survived even at the dye-works, which Linnaeus and contemporary books on textile dyeing had advocated more than hundred years earlier, alongside the new synthetic aniline (from 1856), which was becoming more and more popular. Wool was still at that time regularly dyed with the aid of natural substances: red with cochineal and common madder; bottle green with yellow-wood and steeping in blue-dye-vats; blue with indigo, and coffee brown with yellow-wood, common madder and sandalwood.

Dyeing with native plants was not without problems in Linnaeus’ and Westring’s days, as seen in many notes and comments on the subject. Trying to reconstruct plant dyeing today, according to the principles of that time, can occasion its own different problems too. Sweden has a unique public right of access, so-called “allemansrätt", inscribed in the country’s constitution, which with some exceptions allows for the picking of herbs, leaves, lichen and bark. Notably, the dyer must first of all make sure that plants are gathered with great care; plants which flourished in profusion in the period 1740s to 1840s may well be rare today and therefore protected. And it is not permitted to de-bark trees, other than if one has access to a forest or garden of one’s own. Environmental impact, however, is chiefly evident in the presence of lichens, which were much more abundant before the emergence of industrialisation.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 352, 366-367, 385-387 & 424).

- Hoffman, G.F. Memoires sur l’utilité des Lichens dans la Médecine et dans les arts, 1787.

- Kalm, Pehr, Wästgötha och Bohusländska resa 1742, Stockholm 1977.

- Kungliga Vetenskaps Akademiens Handlingar, KVAH (the Acts of the Royal Academy of Sciences), Online (search: Westring, Johan Peter) Essays about lichen dyeing experiments, 1791-1804.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741…, Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgöta-resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad hår 1746…, Stockholm 1747.

- Nordisk Familjebok, Volume 32, Stockholm 1921. (Search word: col. 86. Westring, Johan Peter).

- Sahlin, Carl, Ett skånskt färgeri vid början av 1870-talet, Stockholm 1928.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm (Information on catalogue card of Johan Peter Westring’s dye samples).

- Westring, Joh. P. Svenska lafvarnas Färghistoria eller sättet att använda dem till färgning och annan hushållsnytta, Stockholm 1805.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE