ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

EMBROIDERIES, SILKS AND VELVETS

– after the Reformation

Catholicism formally ended in 1536 in Denmark, but St Petri church in Malmö already in the previous decade, entered a period of uncertainties and financial difficulties; as a consequence, the church had to sell off gold and silver included in the Medieval embroidered vestments, etc. Furthermore, new acquisitions of ecclesiastical textiles were few in the preceding two centuries after the Lutheran Reformation, as in many other Nordic churches. This essay aims to briefly describe and illustrate the complex realities for a church at this time – from the perspective of its preserved vestments and altar cloths dating from early 1600s and up to 1734.

Chalice cloth with silk and metallic thread embroidery on linen, dating from the early 17th century. This linen fabric was originally white/unbleached and the silks brighter in colour, but despite washing with Marseille-soap and other conservation attempts by The Swedish National Heritage Board, it is still discoloured. Square: 51 cm x 51 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Chalice cloth with silk and metallic thread embroidery on linen, dating from the early 17th century. This linen fabric was originally white/unbleached and the silks brighter in colour, but despite washing with Marseille-soap and other conservation attempts by The Swedish National Heritage Board, it is still discoloured. Square: 51 cm x 51 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.It may be assumed that not all Medieval liturgical vestments and altar cloths were sold off or put to other uses at the time of the Reformation, but instead, they were regularly used in an altered way to fit the traditions within the Lutheran church. This was probably also a necessity from reduced economic circumstances, which, in the case of St Petri, is demonstrated by the that no textiles at all have been preserved originating from the period 1525 up to approximately 1615.

Two of the 17th century textiles once used in St Petri church were the chalice cloth depicted above together with the linen cloth below – both cloths were rediscovered in a cupboard in 1941. The cloth for the chalice had a range of ceremonial functions, but its primary use was to protect the wine from dust and other uncleanliness. This discoloured embroidery on linen was made with tiny cross stitch of red and green silk added with metallic threads of gold and silver. The origin of this stitching is unknown, but speculations can go in three directions:

- The embroidery was stitched in a professional workshop on the Continent and imported by the Malmö merchants or by a St Petri church representative.

- Or the embroidery was of local/Danish production, stitched on imported linen with silks and metallic threads.

- A third alternative could be that only the silk and metallic threads were imported and the linen fabric was woven by one of the linen weavers in Malmö. These weavers were at their most in number during the period from circa 1550 to 1700.

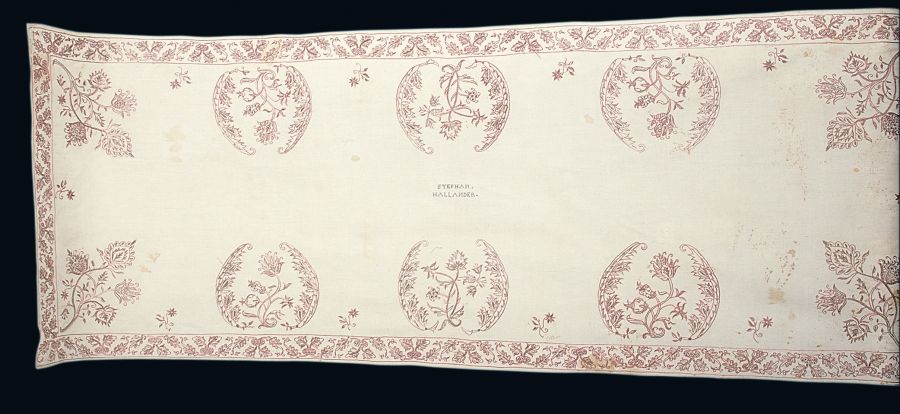

17th century cloth of linen with stem- and satin stitching in pink/red silks – the name “Stephen Hallander” was embroidered in cross stitch. Length 196 cm and width 71 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

17th century cloth of linen with stem- and satin stitching in pink/red silks – the name “Stephen Hallander” was embroidered in cross stitch. Length 196 cm and width 71 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.When the embroidered linen cloth (above) was rediscovered in 1941, it was described as an “altar cloth”, but a later description by The Swedish National Heritage Board is more vague “cloth of white linen”. The origin of the fabric is also somewhat unclear. Still, the textile came to the possession of the St Petri church in the second half of the 17th century, whilst the embroidered name “Stephen Hallander” referred to a local priest who lived in Malmö at the time and died in 1708. The tradition of marking liturgical textiles – with the donor’s name – became increasingly popular during this century. Various individuals’ names, initials or sometimes year for the donation were in this way immortalising a person via the expensive fabrics on display for a long time within the local church.

Antependium dated 1619. The fabric is of Italian origin – cut and uncut velvet on a satin ground – decorated with a wide silk fringe, bobbin laces of gold metallic threads and a fragmented embroidery. This cloth is also a clear example of how the daylight/sun over time bleached that part of the antependium which draped the front of the altar. Length 240 cm and height 104 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Antependium dated 1619. The fabric is of Italian origin – cut and uncut velvet on a satin ground – decorated with a wide silk fringe, bobbin laces of gold metallic threads and a fragmented embroidery. This cloth is also a clear example of how the daylight/sun over time bleached that part of the antependium which draped the front of the altar. Length 240 cm and height 104 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The donors’ names, “Anne Michelsdotter – Jost Holtvig 1619”, were embroidered with metallic threads of gold on the expensive silk fabric. A closer study can trace some more informative details of its history. The man’s name probably had Dutch origin, maybe a merchant who married a Danish lady, Anne Michelsdotter. The couple’s circumstances are otherwise unknown, but clearly, they donated this exquisite fabric to St Petri church in the second decade of the 17th century. The chosen Italian quality was the finest possible – in technique, material as well as strong red dyes (kermes?). These types of large-patterned cut and uncut velvets were favoured for textile interiors, clothing and liturgical textiles in the period 1550 to 1650. The fabric additionally included both professionally made embroideries and bobbin laces. Possibly, this indicates that a Dutch workshop produced the embroideries – due to Jost Holtvig – whilst Malmö had no professional embroiderers at this time. The bobbin laces of gold metallic threads are believed to be Italian, while this type of lace developed in the said area during the two previous centuries and continued to be used for beautifying decorations in the 17th century. These facts taken together show that the antependium most probably was finished off in all its details on the Continent – in more than one workshop – before it was delivered/transported to the Danish town of Malmö.

A silk damask border, once part of an antependium during the 17th century. Length 418 cm and height 11,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

A silk damask border, once part of an antependium during the 17th century. Length 418 cm and height 11,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The possible origin for the silk damask above is regarded as Italy or Spain, but it may also have been woven closer to home, whilst the Danish King Cristian IV, in the year 1619, introduced silk weaving workshops in Copenhagen. The late textile historian Agnes Geijer, who researched this trade, stated that these fourteen workshops, run by Dutch immigrant weavers and dyers, produced patterned silk damasks. However, the trade in the Danish capital was short-lived and reached an abrupt end already in 1627, while the merchants regarded the Danish qualities inferior to the imported wares and, therefore, continued to import silks from the long-lasting weaving workshops in Italy and other areas.

A well-preserved velvet chasuble dating 1671, with the donor’s initials “KCD”, from the St Petri Collection. The decorative back has a high-relief embroidered “Barock style” scene of the Crucifixion – in metallic threads of gold/silver and matching ornament-woven borders. The contrast between the dark red velvet and the gold/silver details is a common characteristic for this period and the preceding century. Height 123 cm and width 87 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

A well-preserved velvet chasuble dating 1671, with the donor’s initials “KCD”, from the St Petri Collection. The decorative back has a high-relief embroidered “Barock style” scene of the Crucifixion – in metallic threads of gold/silver and matching ornament-woven borders. The contrast between the dark red velvet and the gold/silver details is a common characteristic for this period and the preceding century. Height 123 cm and width 87 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Compared to the imported embroideries on the Medieval vestments in the St Petri collection, a chasuble like this was most likely stitched by professional embroiderers in Sweden (Malmö had been part of Sweden since 1658). The late textile historian Inger Estham stated that the liturgical vestments were usually sewn by local tailors, whilst the embroideries and other decorations were added in embroidery workshops. For the circumstances of St Petri church, this probably meant that some professional embroiderers in other parts of the country were commissioned, while Malmö had no such workers in the period from the 1650s to the 1680s. On the other hand, a significant number of tailors were active locally – between 20 and 27 in various years – who were able to sew a vestment like this.

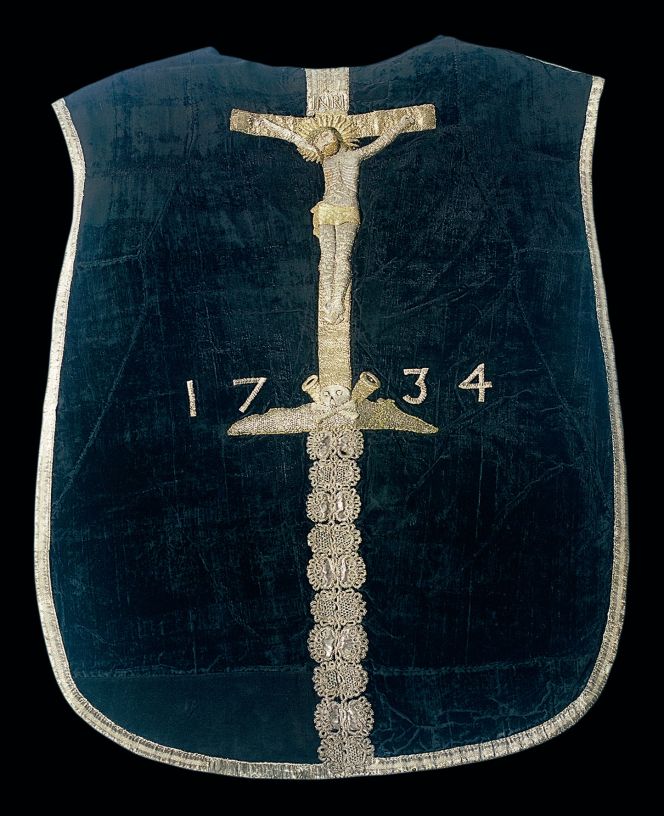

A very similar style chasuble dating 1734, gives evidence too for that such a Crucifix design with a relief embroidery in silver and gold metallic threads added with matching edging of the vestment, was preferred during quite a long period. This style was even living on into the 19th century, but black velvet then became more popular. Furthermore, new acquisitions of liturgical vestments and altar decorations must have been very rare during this period in St Petri church. While this “1734” chasuble is one of two items only preserved from the 18th century and up to the 1870s – a period of 170 years. Back of the chasuble: Height 112 cm and width 83,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

A very similar style chasuble dating 1734, gives evidence too for that such a Crucifix design with a relief embroidery in silver and gold metallic threads added with matching edging of the vestment, was preferred during quite a long period. This style was even living on into the 19th century, but black velvet then became more popular. Furthermore, new acquisitions of liturgical vestments and altar decorations must have been very rare during this period in St Petri church. While this “1734” chasuble is one of two items only preserved from the 18th century and up to the 1870s – a period of 170 years. Back of the chasuble: Height 112 cm and width 83,5 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London. Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of St Petri church textiles, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Kyrkliga textilier i Malmö – från medeltid till barock’, Elbogen pp. 61-135. 2000.

- St Petri Church, Reformation Church Collection, Malmö, Sweden (researched in 1999 & 2000 for above article).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE