ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

EMBROIDERY AND OTHER HANDICRAFT

– A Case Study of a Swedish Aristocratic Family from the 1730s to 1790s

Documents in the Piper Family archive include evidence of frequent needlework, purchases of embroidered furnishing textiles and to some extent other handicrafts during the period 1730s to 1790s. This essay is based on research on inventory lists, auction protocols, correspondence and accounts, which, when looked at more closely side by side, give rediscovered information about daily life in an aristocratic family. The sources reveal that the manor houses included textile objects created by the lady of the house, daughters, et al., together with ownership of professionally made imported embroideries via long-distance trade as well as linen and featherbeds marked with initials, probably made by the housekeeper or other female servants. A selection of contemporary artworks, a reel and a lacquered Chinese sewing box add further knowledge of handicraft and illustrate in what type of settings or furnished rooms such occupations took place.

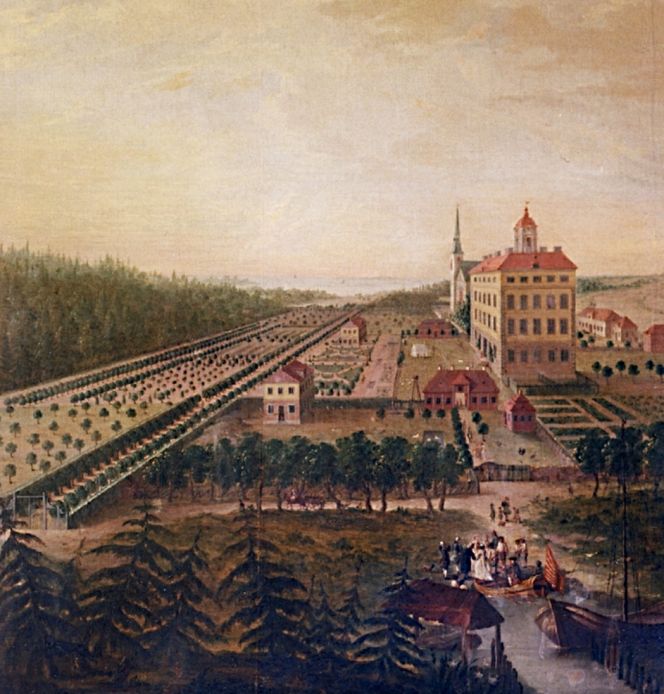

This summer view of Ängsö manor house and garden in Västmanland province dated to circa 1760, is believed to depict Carl Fredrik Piper with family and friends who arrived by boat. The illustration presents a unique insight into one of the aristocratic Piper family’s country houses, a property which had been in their ownership since 1710. One may assume that the extensive garden – with formal ornamental arrangements of flower beds, fruit trees, kitchen garden, a boat house and other useful spaces for the domestic economy – also was a place for leisure activities like embroidery for the lady of the house and her wealthy visitors alike. (Courtesy: Västmanland Museum, Sweden, Vlm-E 7148 /part oil on canvas. Digitalt Museum).

This summer view of Ängsö manor house and garden in Västmanland province dated to circa 1760, is believed to depict Carl Fredrik Piper with family and friends who arrived by boat. The illustration presents a unique insight into one of the aristocratic Piper family’s country houses, a property which had been in their ownership since 1710. One may assume that the extensive garden – with formal ornamental arrangements of flower beds, fruit trees, kitchen garden, a boat house and other useful spaces for the domestic economy – also was a place for leisure activities like embroidery for the lady of the house and her wealthy visitors alike. (Courtesy: Västmanland Museum, Sweden, Vlm-E 7148 /part oil on canvas. Digitalt Museum).One proof of embroidery in the family can be linked to the Countess Ulrika Christina Mörner of Morlanda (1709-1778), traced via a contemporary letter from her oldest son, Carl Gustaf (1737-1803), addressed to his father Count Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770). It may be noted that this wealthy couple used Ängsö manor house as one of their homes during the 1760s, that is to say concurrent with the time of the illustration above. Their son resided in Stockholm at this time, as he since 1757 worked as chamberlain for King Adolf Fredrik (1710-1771). He wrote on May 1763:‘My hope is that dear mother was satisfied with the yarn, at least Jana says that there is no better to be found, and that it after washing will be rose-red, even if it now looks dark. She names it Turkish yarn. ’ Whilst in an undated partly preserved 18th century Inventory from one of the family’s estates reveals that lace-making was part of the handicraft of the Piper family circle. This object was listed as ‘Lace cushion covered with red leather’. That is to say, a bobbin lace cushion.

Representation of bobbin lace making and musical entertainment at Tistad manor house, Södermanland in 1768. This contemporary depiction gives a detailed understanding of such handicraft in a home interior of the Swedish aristocracy. A large number of bobbins, half of these are particularly visible, which indicate that the lady was working on a wide model on a bobbin lace cushion placed on a wooden three-feet-table. Furthermore, the owner of this manor house Fredrik Bengt Rosenhane (1720-1800) was associated with the Court in Stockholm just as several members of the Piper family. Likewise, as both Tistad and Ängsö manor houses were situated at less than a one-day-journey by horse and carriage from the capital. (Private ownership: Tinted drawing by F.W. Hoppe).

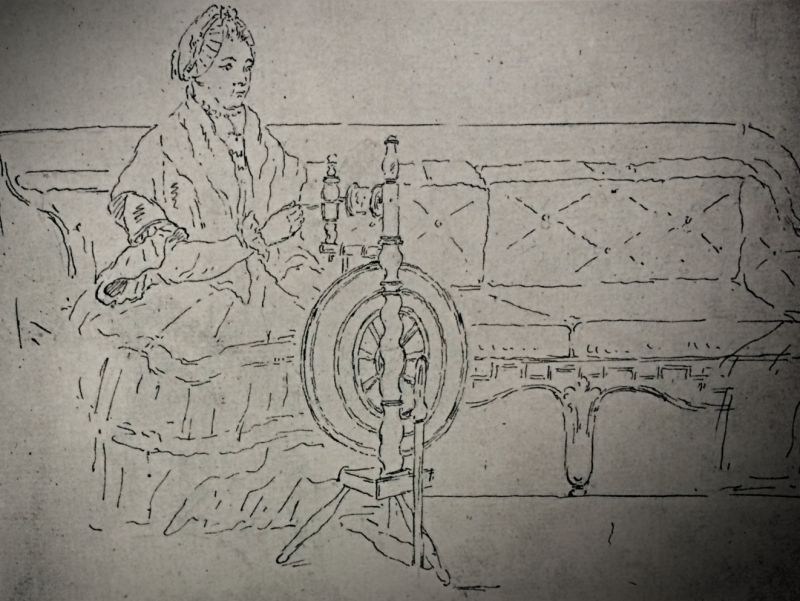

Representation of bobbin lace making and musical entertainment at Tistad manor house, Södermanland in 1768. This contemporary depiction gives a detailed understanding of such handicraft in a home interior of the Swedish aristocracy. A large number of bobbins, half of these are particularly visible, which indicate that the lady was working on a wide model on a bobbin lace cushion placed on a wooden three-feet-table. Furthermore, the owner of this manor house Fredrik Bengt Rosenhane (1720-1800) was associated with the Court in Stockholm just as several members of the Piper family. Likewise, as both Tistad and Ängsö manor houses were situated at less than a one-day-journey by horse and carriage from the capital. (Private ownership: Tinted drawing by F.W. Hoppe). Spinning wool on a wheel by an unknown lady. Judging by the lady’s clothing and the Gustavian style sofa, this activity took place in a home of the Swedish nobility during the 1770s or 1780s. It is highly likely that this scene depicted a wealthy interior not far from the Piper family’s estate – Ängsö manor house – due to that the artist Gustaf Silfverstråhle (1748-1816) lived in the same province of Västmanland, quite close to Stockholm. Furthermore, during a period Silverstråhle was a pupil of the famous architect and engraver Jean Eric Rehn (1717-1793), who had close links to the Court just as the Piper family. Evidence of carding and spinning in the manor house milieu has also been traced via inventories and auction protocols, quoted in translations below. (Private ownership: undated drawing).

Spinning wool on a wheel by an unknown lady. Judging by the lady’s clothing and the Gustavian style sofa, this activity took place in a home of the Swedish nobility during the 1770s or 1780s. It is highly likely that this scene depicted a wealthy interior not far from the Piper family’s estate – Ängsö manor house – due to that the artist Gustaf Silfverstråhle (1748-1816) lived in the same province of Västmanland, quite close to Stockholm. Furthermore, during a period Silverstråhle was a pupil of the famous architect and engraver Jean Eric Rehn (1717-1793), who had close links to the Court just as the Piper family. Evidence of carding and spinning in the manor house milieu has also been traced via inventories and auction protocols, quoted in translations below. (Private ownership: undated drawing). A very detailed Inventory in the year 1758 of Christinehof manor house in southernmost Sweden – a property owned by the Piper family since it was built around 1740 – did however not mention worktables used for embroidery or other textile techniques. The lack of sewing-tables in this inventory, may point to that other activities were preferred during the warm season, whilst the family stayed at this estate during the summer and early autumn months only. Or that the lady of the house and her daughter were not keen on handicraft or that other tables or portable work-boxes were in use, which may have been placed in the shade of a large tree in the garden. | The façade of the three-storey manor house was renovated in 1993 and restored to its original dark yellow colour. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London in 1994).

A very detailed Inventory in the year 1758 of Christinehof manor house in southernmost Sweden – a property owned by the Piper family since it was built around 1740 – did however not mention worktables used for embroidery or other textile techniques. The lack of sewing-tables in this inventory, may point to that other activities were preferred during the warm season, whilst the family stayed at this estate during the summer and early autumn months only. Or that the lady of the house and her daughter were not keen on handicraft or that other tables or portable work-boxes were in use, which may have been placed in the shade of a large tree in the garden. | The façade of the three-storey manor house was renovated in 1993 and restored to its original dark yellow colour. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London in 1994).Portable work-boxes may also have been the natural choice for many women of the nobility, as boxes of this type easily could be transported together with personal belongings – not included in inventory lists – when they travelled from their main home to a summer residence, to friends or elsewhere. It is also notable that this lack of sewing tables and other tools, differ from several other contemporary or later (1749-1792) inventory lists, auction protocols and other handwritten records researched from the same archive. These documents, which are discussed and quoted below in a translation, include a number of either embroidered interior furnishing, sewing-tables or tools that were useful for handicraft.

The family’s high standard of living is primarily visible from a handicraft perspective via luxury objects purchased via the East India trade or imported yarn from the local merchant. Equally as more ordinary craft skills were necessary within the domestic sphere to secure one’s comfortable everyday life – like carding and spinning of wool used for woven woollen featherbeds, marking of linen as well as decorative embroideries for furnishing textiles. These types of objects could either be made by the lady of the house herself, daughters who learned various educational crafts, other female relatives and not least assisting servants or for more complex household textiles of a local or national nature; temporary hired weavers who put up their looms on the manor house or to order objects from professional embroiderers in nearby towns or cities.

Sewing box of dark lacquered wood with gold decorations, 1750-1800. This well-preserved object includes a number of smaller boxes of the same design and a pincushion of green silk, it was probably imported to Sweden during this period from Canton (today Guangzhou) via the Swedish East India Company trade. The box is a good comparison to the inventories, list of shares, correspondence and other documents preserved from the Piper family. A family who not only hold shares in this profitable trading Company, but also repeatedly listed or mentioned East India goods in various documents – lacquered objects seem to have been some of the most sought after pieces together with silk fabric of various qualities. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0094284, Digitalt Museum).

Sewing box of dark lacquered wood with gold decorations, 1750-1800. This well-preserved object includes a number of smaller boxes of the same design and a pincushion of green silk, it was probably imported to Sweden during this period from Canton (today Guangzhou) via the Swedish East India Company trade. The box is a good comparison to the inventories, list of shares, correspondence and other documents preserved from the Piper family. A family who not only hold shares in this profitable trading Company, but also repeatedly listed or mentioned East India goods in various documents – lacquered objects seem to have been some of the most sought after pieces together with silk fabric of various qualities. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0094284, Digitalt Museum).The earlier mentioned Count Carl Fredrik Piper owned ‘six shares or lots in the East India Company’ in the 1750s-60s, to a value of 6,000 Rixdollar silver coins, which with every successful voyage could bring in a dividend of between 30 and 50%. This period was contemporary with several of the inventories, which listed East India goods. Already a few decades earlier though, notes of such desired interior furnishing, can be traced in a letter sent from Stockholm by the general major and Count Gustaf Abraham Piper (1692-1761) to the same Carl Fredrik Piper on 20 August 1736. This particular letter reveals details about the international life and travels of the Swedish aristocracy and how objects of Chinese origin could be taken to Sweden via other geographical routes than the ordinary East India sea trade route. The writer informed about that Count Nils Bonde (1685-1760) had just arrived home from Russia and among many objects he brought back:

- 40 Chinese Draps d’argents [fabric, including silver thread]

- 5 pieces of embroidered cushions

- One black lacquered Chinese bureau

Whilst another possibility to purchase imported goods was via well-renowned local shops, located at a reasonable distance from one of the family’s manor houses. For instance, in a half-year-long account dated May 1772 – the aristocracy had long credits – from the merchants Falkman and Suell in Malmö (southernmost Sweden) the following textile-related goods were noted: silk fabric, gold thread, silver thread and angora goat hair (named ‘kamel garn’ [camel yarn]) included in a long list of other desired wares for the household.

An interesting example of fine silks and velvets with embroidered decorations in the ownership of the aristocratic Piper family, has instead been possible to trace via a document listing the share of furniture for Mr Nils Adam Bielke (1724-1792) at Sturefors manor house in 1749:

‘A piece of furniture from the middle floor by the Cabinet; of green velvet and 15 ribbons, embroidered with yellow and silver threads, on white silk Atlas, with narrow golden galloons [ ]wood over, under and around below, of 5 large and small pieces, lined with fabric. A linen cover for this object.’ Despite his surname Bielke, he was the son of the late Charlotta Christina Piper (1694-1727), who had been Carl Fredrik Piper’s oldest sister.

This well-preserved elegant reel (height 84 cm) – used to wind skeins of silk, cotton or wool into balls – can also be traced to the family of Nils Adam Bielke and Sturefors manor house (mentioned above) via 18th century inventory lists. The reel was made of walnut wood with details of ivory and tortoiseshell, given as a gift to ‘The Countess Bielke in 1760’ by the Queen Lovisa Ulrica (1720-1782). The young Countess, Fredrika Eleonora von Düben (1738-1808), Bielke’s second wife, was regarded as a skilled embroiderer, so this gift must have been in frequent use. Later on in life, she even took part in an exhibition with a silk embroidered landscape motif – at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in 1783, where she had become an honorary member a few years earlier. (Courtesy: Linköping City Library, Curious Cabinet, Linköping, Lin1, 181. alvin-record. 262946).

This well-preserved elegant reel (height 84 cm) – used to wind skeins of silk, cotton or wool into balls – can also be traced to the family of Nils Adam Bielke and Sturefors manor house (mentioned above) via 18th century inventory lists. The reel was made of walnut wood with details of ivory and tortoiseshell, given as a gift to ‘The Countess Bielke in 1760’ by the Queen Lovisa Ulrica (1720-1782). The young Countess, Fredrika Eleonora von Düben (1738-1808), Bielke’s second wife, was regarded as a skilled embroiderer, so this gift must have been in frequent use. Later on in life, she even took part in an exhibition with a silk embroidered landscape motif – at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in 1783, where she had become an honorary member a few years earlier. (Courtesy: Linköping City Library, Curious Cabinet, Linköping, Lin1, 181. alvin-record. 262946).This essay will conclude with two records, which present rediscovered knowledge of possessions linked to textile handicraft and, to some extent, purchased luxury embroideries during the 18th century – for the Swedish aristocracy in general and the Piper family in particular. Firstly, an Inventory from Krageholm Manor House in 1754 gives such insights from several angles:

Bedclothes

1 yellow striped long featherbed, marked with CFP [Carl Fredrik Piper]

[This is one example of many similar featherbeds with various markings]

Coaches and sledges

1 brown French saddle without steelyard, with its stirrups and straps, additionally a cover of green broadcloth with silver embroidery.

Bedcovers

1 red and green embroidered bedcover of silk fabric with linen lining.

Tables

1 small sewing table | 1 ditto | 1 ditto

Wood products

3 Sewing frames | 2 ditto | 2 Spools [for winding yarn] | 3 ditto

Various goods

1 pair of carding brushes for cotton | 1 pair of ditto | 1 pair of carding brushes for wool | 1 pair of ditto | 1 pair of ditto | 1 sewing pad

The second list dates almost 40 years later and has been researched via an auction protocol in 1792 for baron Otto Wilhelm Mörner’s (1733-1791) manor house Toppeladugård, situated in the southernmost province Skåne. Who, just as his wife Ulrika Fredrika Piper (1732-1791) had died in the previous year, without having any heirs as their 17/18 year-old daughter sadly had died in 1790. Tools and embroidered objects are part of the very extensive and detailed document, counting 322 pages. A loom is lacking in the protocol, but several reels, yarn winders and other tools may indicate that – besides handicraft made by the lady of the house, their daughter or other possible female relatives – servants had spun the yarn too, to be used for weaving linen in the household.

Wooden goods

3 Sewing frames | 2 Ditto | 1 Spinning wheel | 1 Reel

Linen sheets

1 pair of linen sheets and 4 pairs of pillowcases, marked in red thread

Various objects

1 pair of carding brushes for cotton | 1 pair ditto | 1 pair of carding brushes | 1 pair ditto | 1 pair ditto | 1 Embroidered fire screen with red and white linen cover | 2 Embroidery cushions with a screw [to fasten on table]

Added objects

1 Reel

Appendix for the auction protocol

1 Spinning wheel | 1 Yarn winder | 1 ditto | 1 ditto | 1 ditto | 1 Reel | 1 Yarn winder | 1 ditto | 1 Reel | 1 Spinning wheel | 1 small sewing frame | 1 Reel | 1 Sewing frame | 1 ditto | 1 small sewing frame | 1 lod [≈13,29 grams] Turkish yarn | 2 lod [≈26,54 grams] White cotton yarn | 11 lod [≈146 grams] reeled linen tow yarn | 3 lod [≈40 grams] Cotton | 1 lod [≈13,29 grams] ditto | 1 Sewing box on a foot

………………………….

Notice: All quotes have been transcribed from original handwritten documents in Swedish and translated into English by Viveka Hansen. This essay is the first of two case studies about embroideries and other handicrafts from these archival sources. The second essay will be a continuation and reflect on the Piper family’s circumstances in this context during the period 1800 to the 1850s.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (research visits: 1990 to 2016).

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004.

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Social Life, Tables and Embroideries – at a Manor House in 1758’. Essays | Textilis. No: LXXVII | August 18, 2017.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive. D/I & D/Ia: Inventories, Piper Family manor houses. | D/IIa 2a: Shares & share of furniture. | E/2 6 (1736), E/II a 2 (1763): correspondence.| D/III 1: Auction protocol. | D/III 4: shop account, Falkman and Suell. | F/IId2 shares).

- Lindberg, Anna Lena, ‘Through the Needle’s Eye: Embroidered Pictures on the Threshold of Modernity’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 31 no. 4, pp. 503-510, 1998.

- Linköping City Library, Curious Cabinet, Linköping, Sweden (Facts about the illustrated reel).

- Mannerstråle, Carl-Filip, Nya huset i Andrarum Anno 1741, Piperska Handlingar No. 1, Christinehof 1991.

- Selling, Gösta, Svenska Herrgårdshem under 1700-talet, Stockholm 1937.

- Svenskt biografiskt handlexikon (search name: Bielke, Nils Adam).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...