ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

FEATHERS AND CLOTHING

– Observations by 18th Century Naturalists

The mentioning of feathers was quite common in 18th century journals and diaries by Carl Linnaeus’ so-called seventeen Apostles. They travelled to more than fifty countries from 1745 to 1799 and included notes of feathers due to the determination of bird species, quills for pens, its usefulness for featherbeds, camels adorned with ostrich feathers, mourning ceremonies, trade purposes, etc – as well as for decoration in clothing, which this study will look closer at. However, such observations were quite limited, but examples can be found in four of these naturalists’ travel journals. A selection of images will further illustrate the practices of embellishing, showing one’s status in society or making garments more beautiful with the assistance of feathers from various parts of the world.

At this period of time, there was already a well established tradition over several centuries to use exotic feathers traded over long-distances with ship and caravans from South America, Asia and other areas (and probably also feathers from wild and domesticated birds closer to home) – to use as a fashionable accessory among the wealthy in Europe. Attached to the hat or as a decoration on top of the coiffure, being the most popular position to expose arrangements of dyed and un-dyed feathers alike. Here exemplified with a portrait of the young socialite Anna Charlotta Schröderheim (1754-91) in Stockholm 1773, by the artist Per Krafft the Elder. (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMGrh 1031).

At this period of time, there was already a well established tradition over several centuries to use exotic feathers traded over long-distances with ship and caravans from South America, Asia and other areas (and probably also feathers from wild and domesticated birds closer to home) – to use as a fashionable accessory among the wealthy in Europe. Attached to the hat or as a decoration on top of the coiffure, being the most popular position to expose arrangements of dyed and un-dyed feathers alike. Here exemplified with a portrait of the young socialite Anna Charlotta Schröderheim (1754-91) in Stockholm 1773, by the artist Per Krafft the Elder. (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMGrh 1031). This material is closely linked to my monograph Textilia Linnaeana: Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade (2017), where feathers and down were part of an in-depth study concerning its usefulness for featherbeds and other filling material in bolsters and cushions. However, visible feathers attached to clothing or headwear were only touched upon in this research. It also has to be pointed out that the 18th century travellers’ various ways of studying different peoples have to be seen in the context of the time – discovery from a European perspective, women's position in society, the European versus people of other cultures, etc.

Fashionably or ceremonially used feathers as decoration on dress and headgear, were often intertwined in a multitude of traditions in many geographical areas during the 18th century. Men, in particular, but also women and children, wore feathers. Among island societies in the Pacific, on Tahiti, for instance, feathers were seen as extremely valuable, particularly if dyed red or if being of naturally red shades, according to the accompanying botanist Anders Sparrman’s observation in 1774 on James Cook’s second voyage.

‘Various feather accessories for wigs and hair. Engraving by R. Bénard after Degerantins’ in 1762. This French engraving gives a multitude of examples of feather accessories, among many uses as a muff (Fig 5) and a feather boa (Fig 7), probably of similar models as observed by Pehr Kalm in a coastal town of Norway in 1748, quoted below. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library no. 29313i).

‘Various feather accessories for wigs and hair. Engraving by R. Bénard after Degerantins’ in 1762. This French engraving gives a multitude of examples of feather accessories, among many uses as a muff (Fig 5) and a feather boa (Fig 7), probably of similar models as observed by Pehr Kalm in a coastal town of Norway in 1748, quoted below. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library no. 29313i).Pehr Kalm made a particularly enlightening description in his journal of the use of magpie feathers and how the natural colours of this and other local birds were preferred compared to the artificially dyed imported feathers. These matters were observed during one of the stop-overs in Kristiansand – along the sailing route by the Norwegian coast on his way to the North American colonies (19 January 1748):

'Everywhere by the villages and farms here in Norway one sees a multitude of magpies, which also nested in the trees close to the houses and often just by and outside the windows. Their flesh is eaten here by many of the gentlefolk; a young farmhand who lives here, though he comes from Finland, gathers the feathers of this bird as well as several other birds, such as ducks, capercaillies etc., the ones that have the prettiest and most gaudy colours, from which he makes feather boas, which women wear around their necks, as well as muffs, which are said to look very attractive. A number of girls in this town wear them and the pretty and naturally coloured feathers of these and other birds for that purpose; and they prefer these muffs to those that are imported from outside, as those that are made locally have natural colours, while the imported ones are artificially dyed.’ (Accessories comparable with the French plates, above and below).

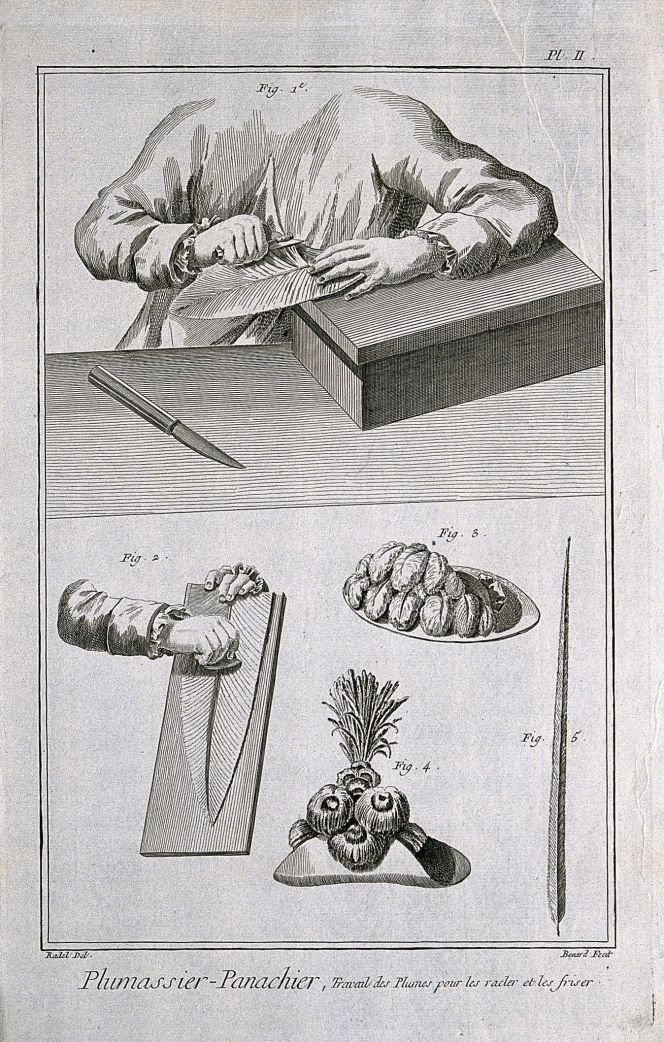

Detailed illustration demonstrating a specialist workshop making feather hats for the European luxury market in 1762. ‘A worker preparing a feather for use as a plume by scraping and curling, above; further preparation of a plume, two hats with plumes and a single plume, below. Engraving by R. Bénard after Radel.’ (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library no. 29257i).

Detailed illustration demonstrating a specialist workshop making feather hats for the European luxury market in 1762. ‘A worker preparing a feather for use as a plume by scraping and curling, above; further preparation of a plume, two hats with plumes and a single plume, below. Engraving by R. Bénard after Radel.’ (Courtesy of: Wellcome Library no. 29257i).More than 50 years later – after a ten-year period abroad in England, Sierra Leone and Guinea – Adam Afzelius, as the final of the Linnaeus Apostles who travelled to other continents than Europe, also wrote some lines on the subject. On 19 May 1799 on his way home to Uppsala in Sweden, his journal reveals that feathers in dress still were popular in towns along the Norwegian south coast. ’The dresses of the women were very whimsical & the most unsettled I ever saw. Some few were dressed as English Ladies, with large English bonnets & Norway petticoats, several with hats & feathers, many with thin bonnets and gauzed blouses’ (Arendale).

From these young naturalists’ North European perspective, many traditional uses of feathers in other parts of the world seemed strange, odd, ugly or pretty enough. Even at a stop-over in Cadix in southern Spain, the former Linnaeus’ student and now ship’s priest Christopher Tärnström, on a Swedish East India Company ship destined for Canton (Guangzhou), reflected on a religious ceremony and some individuals he found ‘strangely dressed’:

‘…Behind him walked 12 to 15 men, strangely dressed in yellow livery and large coloured feather plumes right at the back of their hoods, supposed to represent the soldiers who crucified the Saviour.’ (28 March 1746)

The earlier mentioned Pehr Kalm also made notes of feathers in connection to dress, when visiting Sir Hans Sloane’s collection in Chelsea London on 26 May 1748. Among the very extensive list of items, the following were included:

- ‘The head-dress of a West Indian king made of red feathers, looking pretty enough.

- Feathers of all sorts of birds.’

However, at his main destination, the North American Colonies along the east coast (September 1748 to January 1751), he made no observations linked to feathers on clothing or headgear in the otherwise very frequent descriptions of the Native Americans’ everyday life.

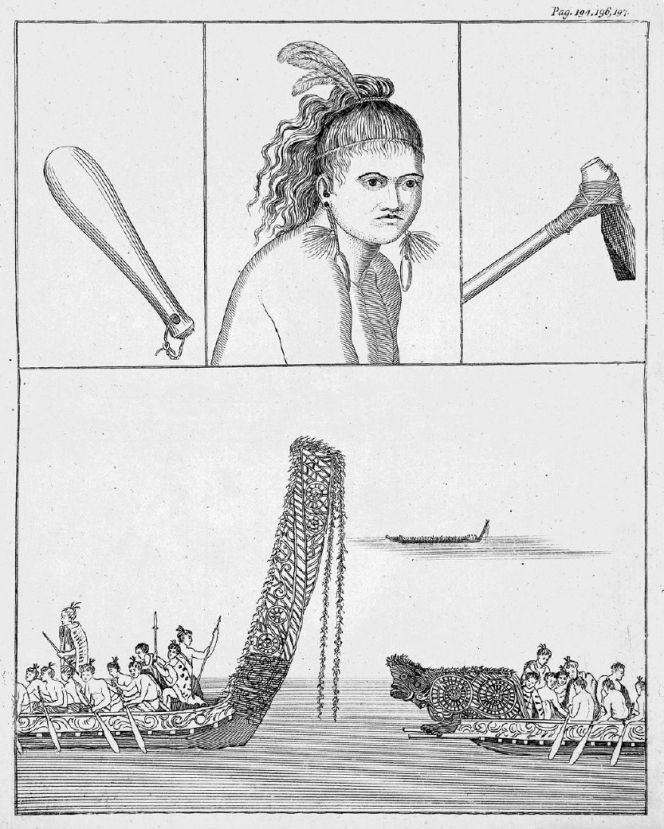

Anders Sparrman’s journal kept during James Cook’s second circumnavigation from 1772 to 1775, includes some further information of feathers as decoration. This Plate of New Zealand men/warriors, gives detailed views from a European perspective (January 1773): ’This visit could not happen without them having adorned themselves with a stinking grease, as is their fashion, feathers in their heads and ears, dressed in their best short tunics with feathers crocheted into them, the man’s hair now tied in a tassel over the crown of his head and decorated with white feathers.’ (Hansen, L. ed,…Vol. 5, Pl. XVIII).

Anders Sparrman’s journal kept during James Cook’s second circumnavigation from 1772 to 1775, includes some further information of feathers as decoration. This Plate of New Zealand men/warriors, gives detailed views from a European perspective (January 1773): ’This visit could not happen without them having adorned themselves with a stinking grease, as is their fashion, feathers in their heads and ears, dressed in their best short tunics with feathers crocheted into them, the man’s hair now tied in a tassel over the crown of his head and decorated with white feathers.’ (Hansen, L. ed,…Vol. 5, Pl. XVIII). To conclude this brief study of observations made by the travelling naturalists, three further examples have been chosen from Anders Sparrman’s journal. Feathers in dress were mentioned regarding their colour and ornamentation as well as for ceremonial uses and the sign of being a “successful” warrior in the South Pacific Ocean.

- ’When the king received among our gifts a tassel of feathers dyed red in England, the entire horde of people marvelled and exclaimed awhé, as they had also done previously on several occasions on seeing the whiteness of our naked bodies compared to their own brown. They themselves collect quite small red feathers from the heads of a small parrot (Peroquet). These feathers they hold in some kind of sanctity.’ (Tahiti, 22 August 1773)

- ‘For adornment the headman had covered each ear with a kind of powder puff of some downy skin of a white bird. Four white feathers had been stuck in his hair, which was tied up on the top of his head. Only warriors who have killed and devoured several of their fellow human beings are permitted to wear such decorations (according to a note in Captain Croizet’s journal).’ (New Amsterdam/Tonga, 7 October 1773)

- ‘Their ornaments also included a variety of plaits and feathers on their headdresses.’ (Easter Island, 13 March 1774)

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012. (Pehr Kalm/Vol. Three pp. 90 & 259. Adam Afzelius/Vol. Four, p. 651. Anders Sparrman/Vol. Five pp. 398, 414, 464, 475 & Plate XVIII and Christopher Tärnström/Vol. Seven p. 309).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Schrubb, Michael, Feasting, Fowling and Feathers – A History of the Exploitation of Wild Birds, London 2013.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE