ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

FISHING NETS AND LINES

– Textile Observations by 18th Century Travelling Naturalists

There was no shortage of interest from the powers of the state in Sweden to improve and resuscitate the popularity of hemp cultivation. His Majesty’s’ edicts in 1737 and commands in 1764, were published in print in order to encourage such cultivation. The latter describes, for instance, the relationship between the areas of usage of flax and hemp in an informative manner: ‘Thus, the two are equally useful and indispensable, albeit for different usages, in that Hemp ought to be used for sailcloth, cordage, rope, string, fishing-tackle, shoe-thread, and more such like, which are used either in water or exposed to force and wear and tear; whereas Flax takes preference in all fine work, such as fine linen, thread, lace etc...’ In travel journals written by the naturalist Carl Linnaeus and some of his apostles, the fibres of fishing nets and lines were also repeatedly noted, and on rare occasions, the nets could be dyed red or brown. A selection of illustrations will give further glimpses into this subject, which over centuries has been deeply intertwined with the history of useful textile raw materials.

![Fishing with a coarse net – made of various plant fibres – was already in use during the Bronze Age, maybe even earlier. A primitive technique which makes it possible to surround and catch the fish for one or several persons working together, depending on the size of the net. Illustrated here from: ’Historia om de Nordiska folken’ [The history of the Nordic people] by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557) printed in 1555. (From: Magnus, Olaus… [1555] 1982. p. 947).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-olaus-magnus-1555-800x438.jpg) Fishing with a coarse net – made of various plant fibres – was already in use during the Bronze Age, maybe even earlier. A primitive technique which makes it possible to surround and catch the fish for one or several persons working together, depending on the size of the net. Illustrated here from: ’Historia om de Nordiska folken’ [The history of the Nordic people] by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557) printed in 1555. (From: Magnus, Olaus… [1555] 1982. p. 947).

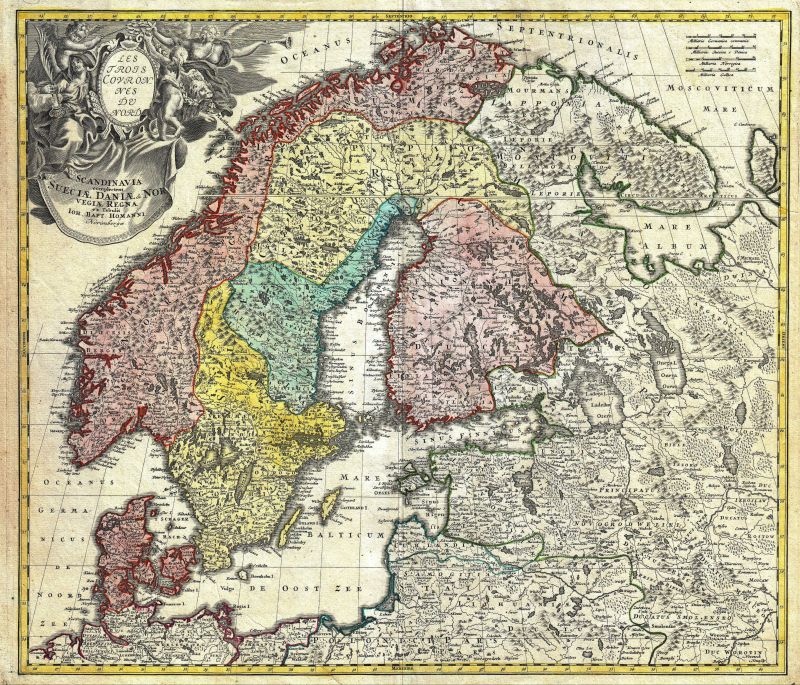

Fishing with a coarse net – made of various plant fibres – was already in use during the Bronze Age, maybe even earlier. A primitive technique which makes it possible to surround and catch the fish for one or several persons working together, depending on the size of the net. Illustrated here from: ’Historia om de Nordiska folken’ [The history of the Nordic people] by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557) printed in 1555. (From: Magnus, Olaus… [1555] 1982. p. 947). About two centuries later, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) made a few observations of hemp fishing nets of various models during his Lapland Journey in 1732. Nets of a sturdy variety were seen in Österbotten for instance (along the coast in the red section to the right, on this contemporary map), on the homeward leg of the journey on 13 August this year. His notes reads: ‘Seals are caught in many ways, either by shooting or netting. The nets are of hemp 3 to 4 fathoms high, the threads as thick as a goose quill’. The reader learns that the nets were made from thick hemp yarn, a material preferred to flax for such sturdy nets. Another reason why hemp was used in that region was that flax is barely hardy enough in the northerly Österbotten, whereas hemp is considerably more frost-tolerant. The text was accompanied by this sketch in his original handwritten journal. (Map, Circa 1730, by J. B. Homann of Scandinavia. Public Domain. | Quote in translation: no. 291. Linnaeus… 2003).

About two centuries later, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) made a few observations of hemp fishing nets of various models during his Lapland Journey in 1732. Nets of a sturdy variety were seen in Österbotten for instance (along the coast in the red section to the right, on this contemporary map), on the homeward leg of the journey on 13 August this year. His notes reads: ‘Seals are caught in many ways, either by shooting or netting. The nets are of hemp 3 to 4 fathoms high, the threads as thick as a goose quill’. The reader learns that the nets were made from thick hemp yarn, a material preferred to flax for such sturdy nets. Another reason why hemp was used in that region was that flax is barely hardy enough in the northerly Österbotten, whereas hemp is considerably more frost-tolerant. The text was accompanied by this sketch in his original handwritten journal. (Map, Circa 1730, by J. B. Homann of Scandinavia. Public Domain. | Quote in translation: no. 291. Linnaeus… 2003). During Carl Linnaeus’ visit to Malmö on the Skåne Journey (16 June 1749), it was not the knotting or tying itself that was observed, but a discussion which took place on how the nets should best be washed. ‘Yarn or net could, so some thought, be washed without soft soap and salt and instantly become as clean as ever if only it was soaked for 8 days and then pounded with a washboard, which had many grooves, and again washed.’ Those nets were most probably intended for herring fishing. Furthermore, in three other of his publications, notes were made about the tradition of dye nets. Alder bark is described in Flora Oeconomica in 1737 as follows: ‘mixed with filings [it] gives a brown-red colour, with which fishermen in Norrland dye their nets’. Whilst from his Öland and Gotland Journey in 1741, it was registered that fishing nets were dyed red with birch bark (Betula), boiled in lye from hazel ashes.

Linnaeus’ apostle Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) made some additional observations of the growing of hemp and the dying of fishing nets on his voyage towards England and the North American colonies. Having set out on his journey in October 1747, Kalm had been able already, after some two months, to record facts about flax and hemp from Grimstad in Norway. There were extensive cultivations of both plants there, and they flourished to such an extent that the peasants hardly ever needed to buy raw materials from beyond their close neighbourhood. On 23 January 1748, between Grimstad and Kristiansand along the Norwegian coast, he noted:

- ’Fishing nets. The flounder nets were dyed brown, which fishermen said had been done with oak and alder bark boiled together; the advantages of this dyeing were said to be two; firstly, the nets thereby become much more resistant to rotting; secondly, the fish do not shun these dyed nets as much as if they were white and un-dyed.’

Another piece of evidence for material used in such nets was registered in his travel journal while staying in Pennsylvania when Kalm noticed a plant called Apocynum cannabinum. This fibre is somewhat coarser in quality than flax – more like hemp – but was dressed, spun and woven into the coarse fabric in the same way. Interestingly, he also noted on 29 September 1748 that the native Americans had formerly from that plant made pouches, fishing nets, fishing lines, etc., for many centuries before the arrival of the Europeans. Locally available raw materials were necessary along the North American coast just as in other parts of the world when it regarded everyday objects like nets and lines for fishing, which had to be renewed due to constant wear and tear.

This coloured drawing of fishermen working with a gill net or cast net, circa 1790s-1800s, in northern Sweden or Finland are interesting comparisons to the written sources by Carl Linnaeus and his travelling apostles during the 18th century of such fishing techniques in local communities. | Artwork by Johan Adam von Gerdten (1767-1835). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, alvin-record: 83141. Public Domain).

This coloured drawing of fishermen working with a gill net or cast net, circa 1790s-1800s, in northern Sweden or Finland are interesting comparisons to the written sources by Carl Linnaeus and his travelling apostles during the 18th century of such fishing techniques in local communities. | Artwork by Johan Adam von Gerdten (1767-1835). (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, alvin-record: 83141. Public Domain). Tying nets with a special wooden needle onto which the coarse yarn could be wound during the work in progress was essential knowledge of fishing families, a craft which had had a long tradition in the coastal regions in the Nordic area. Such a method was used prior to Carl Linnaeus’ and his apostles’ written observations from the 1730s to 1770s, equally as this handcrafted tradition still was in practice during the 1930s – as demonstrated in this photograph. | The fisherman Johan Sjögren tying a fishing net in 1936, Gunnarstorp, Småland province in Sweden. (Courtesy: Kalmar Läns Museum. KLMF.Söderåkra00118. Digitalt Museum).

Tying nets with a special wooden needle onto which the coarse yarn could be wound during the work in progress was essential knowledge of fishing families, a craft which had had a long tradition in the coastal regions in the Nordic area. Such a method was used prior to Carl Linnaeus’ and his apostles’ written observations from the 1730s to 1770s, equally as this handcrafted tradition still was in practice during the 1930s – as demonstrated in this photograph. | The fisherman Johan Sjögren tying a fishing net in 1936, Gunnarstorp, Småland province in Sweden. (Courtesy: Kalmar Läns Museum. KLMF.Söderåkra00118. Digitalt Museum). In another part of the world, the former Linnaeus’ student Daniel Solander (1733-1782) took part in James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage 1768-71. During the continued sailing around the Society Islands – 17 July and 14 August 1769 – the accompanying artist Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745-1771) made notes on the practical properties of many plants on the island of Huahine in his journal, some of which were, or could be, useful for textile purposes. The most important observation was the paper mulberry tree, Morus papyrifera. Another four plants were also studied – including hibiscus species, Phaseolus amoenus and Urtica argentea – from which the local people extracted threads/fibres for nets and fishing lines. There appears to have been a degree of confusion among the voyagers as to which plant was used for the production of textiles when arriving in New Zealand though, but based on historical facts, it is possible to state that it was New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax). That fibre was, besides being useful for clothing, described as practical for all kinds of thread, string and fishing lines among the islanders in the journals by Parkinson as well as the botanist Joseph Banks (1743-1820). Along the Australian coast in 1770, Banks also wrote a lengthy description of the country’s climate, flora, fauna, coastline, hilliness and the way of life of the Aboriginal people. There, he pointed out, from his European perspective, that the inhabitants wore not a single thread on their bodies nor appeared to have any need of, or interest in, owning clothes. A kind of plaited sack for storing things was examined, however, which was described as being ‘something between netting and knitting’. The people must, in other words, have known how to twine thread, presumably of bast/raffia material to have been able to plait such sacks. Those were usually carried on people’s backs, holding their belongings such as arrowheads, fishing hooks and lines, shells, and paint to adorn themselves.

During the second circumnavigation several places were revisited where James Cook had been well received on his first voyage, when Daniel Solander and Joseph Banks had been the accompanying botanists. This time, it was Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-1798) and his son George Forster (1754-1794) who, together with the former Linnaeus’ student Anders Sparrman (1748-1820), botanised, carried out zoological investigations and collected ethnographic objects. Collecting appreciable quantities of ethnographic curiosities appeared to be more of a priority this time, as most of the plants had already been “discovered” during the previous voyage. One of the larger ethnographic collections, Forster’s Collection, is to be found today in Göttingen and is an example of a very rich accumulation of artefacts transported back to Europe. Besides, a non-inconsiderable part of the ethnographic objects was of a textile nature, and some artefacts related to the raw materials and the manufacture of textiles are used here as examples. From the Society Islands are still preserved: fishing nets made from Hibiscus tiliaceus, rope from coconut fibre, ribbons plaited from coconut, grass and flax-like fibres and a spindle. From New Zealand the collection listed samples of New Zealand flax and also exemplars of such fibre before retting. Additionally, Anders Sparrman made a note in his travel journal about fishing nets from New Caledonia on September 1774: ‘Their fishing is done with hooks, harpoons or fine and coarse nets, even very coarse ones. The latter is made for capturing turtles.’

A rare example of a preserved plaited fishing line of hemp, with a hook of iron wire and lead weight. The tool was sold to the museum collection in 1891, an object which originally had been used in Jokkmokk, Lapland in northernmost Sweden. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0070578. Digitalt Museum).

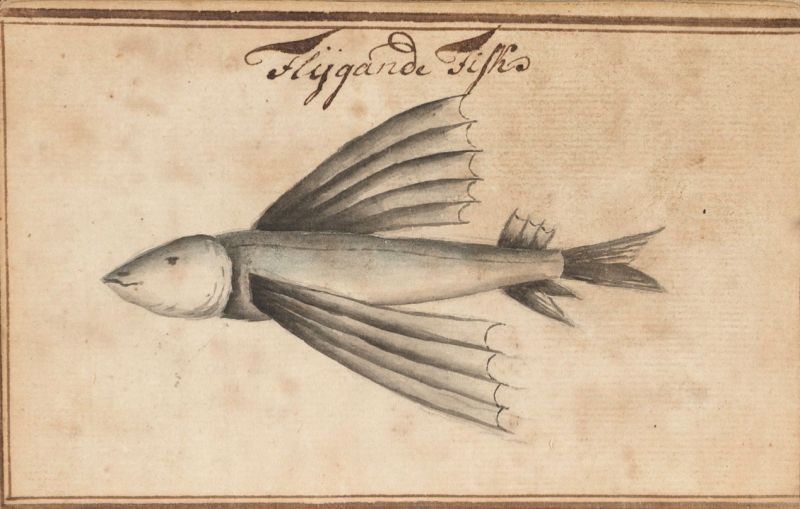

A rare example of a preserved plaited fishing line of hemp, with a hook of iron wire and lead weight. The tool was sold to the museum collection in 1891, an object which originally had been used in Jokkmokk, Lapland in northernmost Sweden. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0070578. Digitalt Museum).  In concluding words. The method of using a fishing line of hemp or other textile fibres, similar to the one illustrated above, must be seen in an extended geographical perspective – even if the choice of raw material rarely seems to be mentioned in written sources. In its simplicity, such a capturing tool had a wide global tradition, stretching over many centuries in coastal communities. Some added thoughts of fishing with line and hook can also be glimpsed from the handwritten journal by Carl Fredrich von Schantz’ (1727-1792), an account which has inserted watercolour plates. The illustrations, which reveal informative observations of everyday life as he experienced on a voyage towards Canton with a Swedish East India Company ship from 1746-49. This was almost concurrent in time with three of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles who travelled with the same Company. Von Schantz’ notes of how they caught the illustrated ‘flying fish’ close to the Equator reads in a translation: ‘… one takes a strong line and then a large iron hook to the end of the same, and on the hook one fastened a half mark of pork…’ Besides that the plant fibre was possible to find locally, like hemp in Sweden or hibiscus on the Society Islands, an equally important feature was that the chosen material for fishing lines and nets were of a strong sturdy quality. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 40/17r).

In concluding words. The method of using a fishing line of hemp or other textile fibres, similar to the one illustrated above, must be seen in an extended geographical perspective – even if the choice of raw material rarely seems to be mentioned in written sources. In its simplicity, such a capturing tool had a wide global tradition, stretching over many centuries in coastal communities. Some added thoughts of fishing with line and hook can also be glimpsed from the handwritten journal by Carl Fredrich von Schantz’ (1727-1792), an account which has inserted watercolour plates. The illustrations, which reveal informative observations of everyday life as he experienced on a voyage towards Canton with a Swedish East India Company ship from 1746-49. This was almost concurrent in time with three of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles who travelled with the same Company. Von Schantz’ notes of how they caught the illustrated ‘flying fish’ close to the Equator reads in a translation: ‘… one takes a strong line and then a large iron hook to the end of the same, and on the hook one fastened a half mark of pork…’ Besides that the plant fibre was possible to find locally, like hemp in Sweden or hibiscus on the Society Islands, an equally important feature was that the chosen material for fishing lines and nets were of a strong sturdy quality. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 40/17r).Sources:

- Banks, Joseph, The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771. Ed. by J. C. Beaglehole, 2 vol., Sydney 1963.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Three. Pehr Kalm’s journal & Vol. Six. Anders Sparrman’s journal).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 34, 214, 217, 219, 230, 293, 323-324, 360 & 429-431).

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige befalling…plantera och bereda hampa och lin..., Stockholm 1764.

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, Sweden (National Library of Sweden); ‘En kort beskrifning uppå en Ostindisk resa till Canton uthi China. Förrättat af Carl Fredrich von Schantz Ifrån åhr 1746 Till åhr 1749.’ (Manuscript: M 292).

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Kundgiörelse, Angående Hampe Sädets befrämjande uti Riket, 1737.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa…1741, Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749…, Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Flora Oeconomica 1737, Uppsala, facsimile 1971.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. Published by Algot Hellbom, Sigurd Fries and Roger Jacobsson. vol. I., Umeå 2003.

- Magnus, Olaus, Historia om de Nordiska Folken [first published in Rome 1555], Stockholm 1982.

- Parkinson, Sydney, A Journal of a voyage to the south seas in his Majesty’s ship The Endeavour, London 1784.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE