ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

FRENCH TAPESTRIES, PAINTED LINEN AND WALLPAPERS

– at a Manor House in 1758

Observations learned from a detailed Inventory at a manor house in southernmost Sweden will focus on French tapestries, painted linen and wallpapers. The listed materials from room to room, together with contemporary letters and account books, give fascinating details of everyday life, shopping, the desire for luxury, domestic economies and material culture of the tenant in tail Carl Fredrik Piper and his family in the mid-18th century. Recently made acquisitions by the National Museum in Stockholm of four Beauvais tapestries – will also reveal some rediscovered possible links to the Piper family’s tradition of transporting fine textiles between their manor houses over many decades.

-800x1011.jpg) This is one of four French Beauvais manufactured tapestries acquired by the National museum in Stockholm during 2016 – named ‘The Elephant, from Grotesque de Berain’, woven circa 1696-99 of wool and silk in the size of 284 x 224 cm. The tapestry was originally ordered by Carl Piper and from preserved correspondence it is known that the group of four wallhangings were installed in the family’s grand property in the old town of Stockholm in 1699. During periods of the 18th century, these portable costly objects seem to have been in use at the Piper family’s manor houses situated in various provinces of the Swedish countryside (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, NMK 299A/2016.)

This is one of four French Beauvais manufactured tapestries acquired by the National museum in Stockholm during 2016 – named ‘The Elephant, from Grotesque de Berain’, woven circa 1696-99 of wool and silk in the size of 284 x 224 cm. The tapestry was originally ordered by Carl Piper and from preserved correspondence it is known that the group of four wallhangings were installed in the family’s grand property in the old town of Stockholm in 1699. During periods of the 18th century, these portable costly objects seem to have been in use at the Piper family’s manor houses situated in various provinces of the Swedish countryside (Courtesy of: Nationalmuseum, NMK 299A/2016.)The oldest wall coverings at Christinehof Manor House in 1758 may have been these four woven tapestries (one illustrated above), which, according to the Inventory, decorated the Drawing-room of the Yellow Chamber on the second floor. Listed as: ’The room is covered with French Gobelin tapestries taken from Sturefors, and green broadcloth above the doors’. Judging by these details, the tapestries were either woven at the well-established Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris – which from 1694-1708 worked during reduced circumstances – or more likely at the Beauvais tapestry manufacture, where to a greater extent, sold to foreign wealthy costumers. The note about that the tapestries previously had been used in one of the Piper family’s other homes demonstrates the frequent rearranging of household objects, transported from one property to another over the decades. ‘Sturefors’ in the province of Östergötland was purchased by Carl Piper (Carl Fredrik’s father) already in 1699 and rebuilt to an even larger manor house in 1704. It is somewhat uncertain what the listed tapestries in the 1758 Inventory actually depicted, but the period favoured motifs as historical events, so-called “Grotesques” and idyllic garden scenes. However, judging by the preserved wall coverings as well as written contemporary sources, it appears to be that the elephant tapestry as one of four specially ordered tapestries, woven more than 60 years prior to the Inventory, had been moved around within the aristocratic family when circumstances changed. In the mid-18th century, between 1742 and 1758, the tapestries had found their way to one of the summer residences – Christinehof in southernmost Sweden.

Additionally, two other tapestries were stored in the Vault, listed as ‘one lined Gobelin tapestry’ and ‘one Turkish ditto’. The one named ‘Turkish’ does not necessarily allude to a woven quality but rather a design painted on linen cloth. Walls were also lined with this type of painted coarse linen cloth in six rooms. These were elegant imitations of woven tapestries, but less expensive. Sometimes, it is even mentioned in historical documents as ‘Painted Gobelin Tapestries’ or in the words ‘the wall decorations are Gobelin imitations, painted with ships, forests and people’. However, in this particular listing from the manor house in 1758 – the type was described in five rooms as ‘Saxon tapestries’ with patterns of ‘Landscape scenes and the Count’s coat of arms’, ‘The dream of Pharaoh and the Count’s coat of arms’ or only ‘Landscape scenes’. The name ‘Saxon’ is somewhat uncertain; it may be a particular painting technique or choice of details in the patterning.

Such lengths of linen cloths were stretched on the walls, and the artistic work was done on-site, whilst these landscape scenes etc, probably covered an entire wall, and for each room, an individual design was chosen. The main motifs were most likely repeated by the artists when fulfilling their commission from one manor house to the next; they were initials and coats of arms, which gave the decorations a unique representation. The artists usually preferred to work in distemper, which to some extent was transparent to increase the illusion of a woven tapestry. These were impressive and luxurious decorations demonstrating a family’s high standard of living. The problem with this type of wall decoration was mainly its water- or glue-based colouring, making the linen surface impossible to clean properly. The soot from the large open fires further reduced the durability.

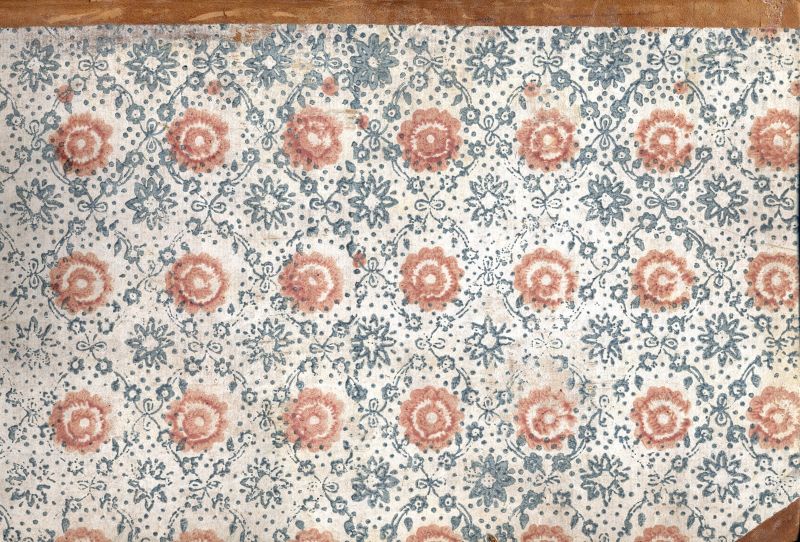

This account book dating 1775, from one of the other homes of the Piper family, is a representative example of how pieces of 18th century wallpapers have been preserved. A typical mid-century design with its flowery motifs in blue and pink on a white ground, it may be assumed that some rooms at Christinehof manor house were decorated with similar wallpapers at the time of the Inventory in 1758. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. G/VI 5). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This account book dating 1775, from one of the other homes of the Piper family, is a representative example of how pieces of 18th century wallpapers have been preserved. A typical mid-century design with its flowery motifs in blue and pink on a white ground, it may be assumed that some rooms at Christinehof manor house were decorated with similar wallpapers at the time of the Inventory in 1758. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Piper Family Archive, no. G/VI 5). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Wallpapers made of paper decorated 13 rooms according to the 1758 Inventory, in style like above and in ‘marbling’ or ‘wave’ designs, placed in various rooms on all three floors. On the Ground Floor, in the young counts’ chamber, one design was listed as on a ‘yellow ground and blue festoons’. Whilst on the First Floor, the room used by the Countess’ maid had ‘green wall decorations of paper with white borders’; similarly, the room of the young Lady’s maid was decorated with ‘wallpapers on green ground and bouquets’. Two other rooms were ‘decorated to 2/3 with wallpapers, on black ground and blue leaf pattern with red flowers’ together with ‘wallpapers on light red ground with checked flowery lattice’. The Second Floor included ‘blue marbled wallpapers’ in the cabinet and ‘green and white patterned, green marbled wallpapers with gold coloured flowers’ as well as ‘on green ground with bouquets’ in rooms situated in the righthand wing of the manor house.

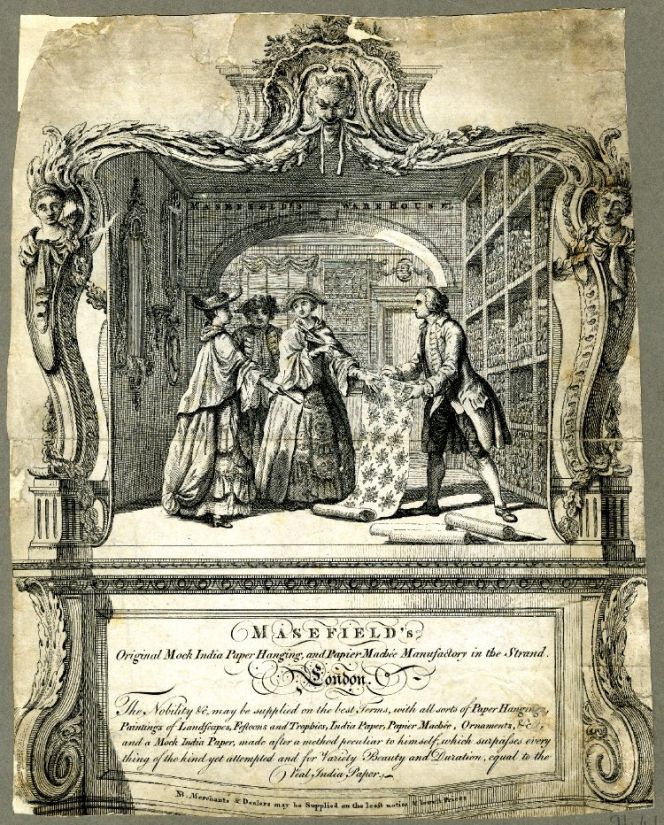

This fashionable London shop with its wealthy customers was depicted on a trade card dating around 1758 – just the same year as the Inventory – which gives an interesting glimpse of expensive wallpapers for sale. In London, Paris or Stockholm alike it may be assumed that the wealthy clientele and the assortment of products were quite similar. For instance, the Inventory lists various origins for the wall decorations as French or East Indian and this depicted shop interior particularly focused on “India paper” of several designs. Imported goods of all variations were often emphasised in prints as well as hand-written documents or personal letters. (Courtesy of: British Museum, London, Collection Online, Trade-card/prints, Heal,91.41).

This fashionable London shop with its wealthy customers was depicted on a trade card dating around 1758 – just the same year as the Inventory – which gives an interesting glimpse of expensive wallpapers for sale. In London, Paris or Stockholm alike it may be assumed that the wealthy clientele and the assortment of products were quite similar. For instance, the Inventory lists various origins for the wall decorations as French or East Indian and this depicted shop interior particularly focused on “India paper” of several designs. Imported goods of all variations were often emphasised in prints as well as hand-written documents or personal letters. (Courtesy of: British Museum, London, Collection Online, Trade-card/prints, Heal,91.41).Overall, wall decorations of paper had become increasingly popular in wealthy Swedish homes around the mid-18th century. For the Piper family, printed or painted papers – of imported as well as domestically manufactured types – would most likely have been purchased from traders in Stockholm or in the more closely situated city of Malmö (Johan Daniel Rosenberg who had a mirror and wallpaper manufacture at this place) if used for their manor houses in the southernmost province of Skåne. In conclusion, one enlightening example may be gleaned via correspondence from Carl Gustaf Piper to his father, Carl Fredrik, in 1764, when the son had engaged the well-renowned engraver and architect Jean Eric Rehn to assist him in this matter. The son mentioned in his letter sent from Stockholm: ‘He also gave me suggestions of extraordinarily beautiful wallpapers…So, if my dear father prefers these for the cabinet, I need to have the measurements for the width and height of each wall before ordering from Rehn…they are just as being painted on linen’. The last sentence also indicates that it was still preferred that wallpapers made of paper appeared to be painted on a textile material.

This is the seventh essay based on the Inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House. Quotes from the documents are translated from Swedish to English.

Sources:

- British Museum, London, Collection online (Search words: “trade cards wallpaper”).

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (research visits).

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004 (pp. 20-24 & 38-62).

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof (Piper Family Archive, no D/Ia: Inventory 1758 & D/IIa2: correspondence).

- Laine, Merit, ‘Four Beauvais Tapestries with Grotesque Motifs’ (pp. 111-114), Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm, Volume 23, 2016. (Also including the C19th to C21st history of these tapestries).

- Lindblom, Jack, Vävda tapeter, Stockholm 1979 (pp. 122-131).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE