ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

FROM FLAX TO LINEN

– Observations by Carl Linnaeus and Artworks illustrating these Textile Traditions

The preparation of flax requires a biological stage in which either water or dry retting is used to separate the fibre from the bast, after which the material must be thoroughly dried before mechanical working can begin with the help of breaking, swingling and heckling. Yarns were then spun to desired qualities and followed by bleaching, which either was applied to a ready-spun thread or, after the cloth was woven, to be spread out and bleached on the snow in winter or on the grass during warm sunny days in summer. The naturalist Carl Linnaeus made repeated observations about the subject from the provincial tours in Sweden during the 1730s and 1740s. This essay will look closely at tasks described in his journals and a selection of notes and paintings linked to flax handling and manufacturing linen. Circumstances taken into account included; knowledge about agricultural methods, weather conditions, a multitude of craft skills, the advantages for the domestic economy as well as basic needs for linen used for clothing or more luxurious desires for damask woven tablecloths.

This somewhat later and romanticised depiction – mid-19th century – of flax handling in Delsbo parish, Dalarna province in Sweden, gives an idea of such tasks for women and men alike. Tools and practices were very similar in the previous century. The retting in water, with flax sheaves tightly packed and attached to an adapted frame is particularly enlightening. Other works displayed were drying the flax sheaves on a fence, breaking the flax fibres, heckling etc. | Oil on canvas by Joseph Wilhelm Wallander (1821-1888). (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, NMA.0035036).

This somewhat later and romanticised depiction – mid-19th century – of flax handling in Delsbo parish, Dalarna province in Sweden, gives an idea of such tasks for women and men alike. Tools and practices were very similar in the previous century. The retting in water, with flax sheaves tightly packed and attached to an adapted frame is particularly enlightening. Other works displayed were drying the flax sheaves on a fence, breaking the flax fibres, heckling etc. | Oil on canvas by Joseph Wilhelm Wallander (1821-1888). (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, NMA.0035036).Flax as a useful cultivated plant was studied repeatedly during Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) tours of Skåne, Öland and Gotland, on his way to Lapland and also in Dalarna. Linum usitatissimum was the name he gave to the beautiful and practical plant; the precise meaning of the Latin name is “highly useful flax”. Owing to the plant’s valuable properties, the cultivation of flax was encouraged, both on a small and large scale, as avoiding any needless import of linseed, flax fibre, linen yarn and ready-made cloth was considered to be good for the national economy. However, it must be pointed out that replacing some imported top-quality fabrics, such as the highly commended brown holland, with domestic versions was hardly even considered a possibility. Imports could not be entirely excluded. The mercantile thinking of the time was that flax, as well as many other useful plants or animals as possible, were to be cultivated and bred in Sweden for the country to become more self-sufficient in raw materials for textiles etc.

There were, moreover, several contemporary observers or cultivators of flax or owners of flax plantations who recorded their findings on the handling of flax in various instances, which complement Linnaeus’ studies. One of them was Stephen Bennet (1691-1757), who in 1738 published a detailed 80-page-long guide in the Swedish language on the potential of the textile plant for Sweden, Finland, Ireland, England, the present-day German region, dealing with anything from soil types, sowing, pulling, retting, breaking, swingling, heckling, spinning, trading in yarn, weaving of unbleached linen, weavers’ pay, bleaching of linen, and sorting, trading and pricing of linen fabrics of different qualities.

Flax is usually sown around the middle of May, and it flowers towards the end of June. The flax may be harvested at different times after flowering, depending on the type of spinning material for which it is intended and the degree of importance afforded to the harvesting of seeds; the regular stage of maturity, however, is between 30 and 35 days after flowering has reached its peak. That is also likely to have been the usual time of harvesting in Linnaeus’ days, as on 27 July 1749, he wrote from northern Skåne: ‘The flax which was now ripe was threshed, tied into bundles, put up on poles to dry when the roots were turned to the south.’ In other words, the flax was pulled and gathered into bundles which were tied together and dried. The next step entails ripping off the seeds and then the retting (see image above) before the flax can be further processed, but that was not procedures that were recorded as having been witnessed during the provincial tours.

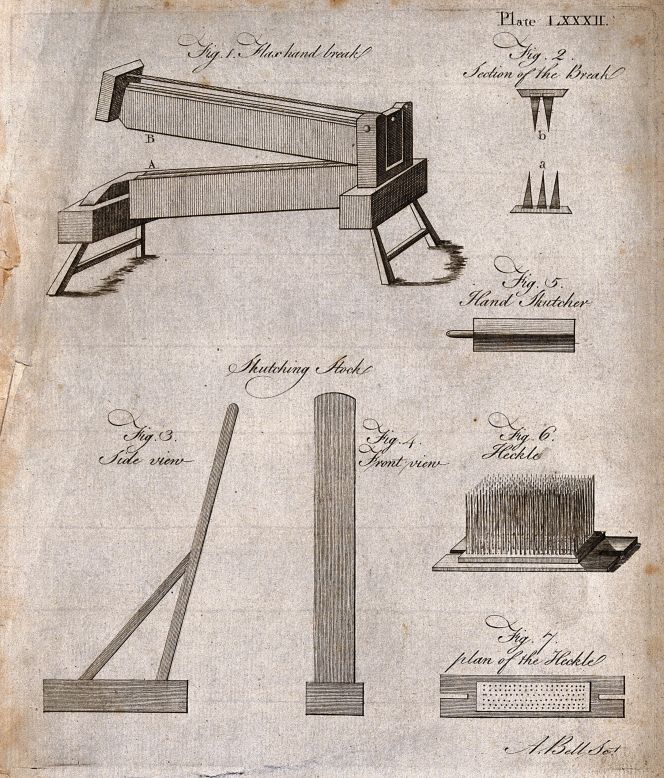

‘Equipment for processing flax’. This 18th century engraving printed in London in an unknown year demonstrates that tools for flax were similar in design to Swedish models in a much larger geographical area at the time. Flax hand break, skutching stock, hand skutcher/swingler and heckle are all necessary tools – from retted and dried flax sheaves to shiny flax fibres ready for spinning. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images, No: V0024073).

‘Equipment for processing flax’. This 18th century engraving printed in London in an unknown year demonstrates that tools for flax were similar in design to Swedish models in a much larger geographical area at the time. Flax hand break, skutching stock, hand skutcher/swingler and heckle are all necessary tools – from retted and dried flax sheaves to shiny flax fibres ready for spinning. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images, No: V0024073).The removal of the bast from the flax fibre begins with the breaking when most of the bast is loosened through various methods such as beating, pounding or bruising. Linnaeus observed one method during his journey in Skåne at Tunbyholm on 6 June 1749, writing: ‘...there it was bruised in a skilful manner with old men and womenfolk sitting on the flax break and steering from behind.’ That men were involved in the work would have been a common occurrence, seeing as the bruising is physically demanding work. From the same province, there is also mention in a municipal court protocol from 1746 that it was possible to have one’s flax bruised against payment outside the town of Malmö because of the risk of fire, ‘...that nobody for 10 Rixdollars and penalty may bruise any flax in the town, but can instead for a reasonable payment make use of the bruising huts which some people have constructed outside the town...’

In northern Sweden, another method of beating and pounding the flax was used as a preparatory step for breaking. On that subject, Linnaeus wrote from Hälsingland on his way to Lapland in 1732: ‘Wherever there was a river, a wheel was driven [in turn] driving a hammer for pounding the flax, yet so that a fall-trap on the floor was taken up when it was to be stopped.’ Because of the large quantities of flax to be prepared in that region, a semi-mechanised process had therefore been developed by using hydro-power. In most parts of the country, what was used to remove the final shives from the flax fibre was a flat-bladed swingle tool which was pounded against the flax. That particular step and the heckling, when the flax is pulled through nails on a board, were not however seen by Linnaeus on his travels. The two procedures were purely women’s work, which is evident in that swingle tools were principally a gift for the bride-to-be. The objects are usually beautifully painted or carved with motifs, initials or dates and are mainly kept intact in the provinces of Skåne and Hälsingland from that time. At this stage of the process, the shiny bunches of tow were of an unbleached/grey colour, but the 18th century ideal was white flax; thus, the material had to be bleached. Linnaeus gives an account of that from Lärkesholm in Skåne on 25 July 1749: ‘Bunches of tow were seen here being bleached and made as snow-white as silk wadding, from which fustian was woven’. It was more common, though, to delay the bleaching until after weaving, as strong bleach has a weakening effect on the fibre and may that way make the material more difficult to handle both for spinning and weaving.

This oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816), signed in 1798, demonstrates ‘A maid heckling flax’, with the heckle provisionally tied to a chair. The maid seemed to have been halfway through the task when she injured her finger on the very sharp rows of pointed needles. Such a heckle was used to give the fibre its final shiny “combed” look before the spinning at the same time as the flax tow was separated – here sorted to the right side of the chair – which later could be spun to coarser qualities. (Courtesy: Private Ownership. Photo, Bukowskis in Stockholm).

This oil on canvas by Pehr Hilleström (1732-1816), signed in 1798, demonstrates ‘A maid heckling flax’, with the heckle provisionally tied to a chair. The maid seemed to have been halfway through the task when she injured her finger on the very sharp rows of pointed needles. Such a heckle was used to give the fibre its final shiny “combed” look before the spinning at the same time as the flax tow was separated – here sorted to the right side of the chair – which later could be spun to coarser qualities. (Courtesy: Private Ownership. Photo, Bukowskis in Stockholm). The next stage for the shining flax fibre is to be spun into fine thread on a spinning wheel and then to wind the yarn onto a reel making equally sized skeins, so being able to estimate the amount of linen thread. The same artist's oil on canvas from the 1780s to 1790s illustrates both these textile tools. However, for this depiction, Pehr Hilleström did not choose a servant in her everyday setting, but instead, a wealthy young lady occupied with industrious handicrafts in her drawing room at the manor house. Such a home was either situated in the Swedish countryside or a large residence in Stockholm. (Courtesy: Private Ownership. Photo, Bukowskis in Stockholm).

The next stage for the shining flax fibre is to be spun into fine thread on a spinning wheel and then to wind the yarn onto a reel making equally sized skeins, so being able to estimate the amount of linen thread. The same artist's oil on canvas from the 1780s to 1790s illustrates both these textile tools. However, for this depiction, Pehr Hilleström did not choose a servant in her everyday setting, but instead, a wealthy young lady occupied with industrious handicrafts in her drawing room at the manor house. Such a home was either situated in the Swedish countryside or a large residence in Stockholm. (Courtesy: Private Ownership. Photo, Bukowskis in Stockholm).On his way to Lapland in 1732, when passing through Hälsingland, Linnaeus wrote that ‘the country’s foremost work is this linen manufacture’. That brief note referred to Flors Linnemanufaktur (Linen Manufacture of Flor), which formed a substantial part of the Swedish manufacture of woven linen production since its foundation in 1729. Flor reached its heyday in the years between 1753 and 1793 with its Hall Right and 2,000 spinning women who supplied the manufacturer with yarn of different qualities. The Hall Right of manufacture was valuable, but it also entailed a complicated set of regulations of supervision and legal implications for each manufacturer to follow. Kongl. Maj:ts Utfärdade HallOrdning, Och Allmänne FactorieRätt... (His Majesty’s Directives on Rules for Halls and General Factory Rights...) describes in nine sections all those directives, including the following:

- ‘The Hall Right should not only have thorough knowledge and registers of all Manufactures, Factories and mills in the town, and their condition and kinds of production; but also of all their practitioners, servants, craftsmen and labourers. Moreover, the Right [of manufacture] should hold records of all the sorts and goods, their Quantities and Qualities, which are fabricated annually at those establishments and workshops...’

Several of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles also mentioned the brown holland or linen: Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) bought ‘brown holland for 4 Shirts with cuffs’ on his arrival in England in 1748, while Göran Rothman’s (1739-1778) estate inventory listed ‘3 shirts of fine holland, 4 ditto of coarser brown holland, 10 ditto with cuffs, 6 ditto ready cut’. This oil on canvas by Jacob van Ruisdael shows the extensive bleaching grounds at Harlem in Holland as early as the 1660s. The Swedish Linen Manufacture of Flor, which Linnaeus visited in 1732, also carried out the bleaching of linen fabrics on a smaller scale using similar methods. A 60-page publication with four fold-out pictures by Herman Kolthoff (1738) additionally shows an interesting collocation of the significance of the linen bleach works in Harlem, not only for the Dutch themselves but also for the considerable export of the high-quality stuff. The publication explains chiefly what types of buildings and tools were needed, the process and handling of the bleaching of yarn and weavings at Harlem. (Courtesy: Kunsthaus, Zürich, Switzerland).

Several of Carl Linnaeus’ apostles also mentioned the brown holland or linen: Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) bought ‘brown holland for 4 Shirts with cuffs’ on his arrival in England in 1748, while Göran Rothman’s (1739-1778) estate inventory listed ‘3 shirts of fine holland, 4 ditto of coarser brown holland, 10 ditto with cuffs, 6 ditto ready cut’. This oil on canvas by Jacob van Ruisdael shows the extensive bleaching grounds at Harlem in Holland as early as the 1660s. The Swedish Linen Manufacture of Flor, which Linnaeus visited in 1732, also carried out the bleaching of linen fabrics on a smaller scale using similar methods. A 60-page publication with four fold-out pictures by Herman Kolthoff (1738) additionally shows an interesting collocation of the significance of the linen bleach works in Harlem, not only for the Dutch themselves but also for the considerable export of the high-quality stuff. The publication explains chiefly what types of buildings and tools were needed, the process and handling of the bleaching of yarn and weavings at Harlem. (Courtesy: Kunsthaus, Zürich, Switzerland).Handicraft in farming communities was a dominating factor for weaving linen cloth, whilst most of the country’s textile manufacturers and professionally active artisans worked in the larger towns and cities in 18th century Sweden. Malmö, in the southernmost province, was such a place where linen weaving had traditions stretching hundreds of years back. At the time of Linnaeus’ visit, the town had six masters of the craft, assisted by journeymen, one of whom was Paul Flesinski, who acquired his membership of the Linen Weavers’ Guild in 1725 and worked there until his death fifty years later. However, linen thread was not only important for household linen as tablecloths and napkins or clothing like linen shirts, but equally so for manufacturing a wide selection of ribbons, lacework and other textile furnishing details desirable for various strata of society.

In this wedding portrait dated 1739, around the same decades as his provincial tours, Carl Linnaeus is seen wearing a formal, elegant, red collar-less coat, probably of fine broadcloth, with a matching waistcoat and a ruffled linen shirt. (Courtesy: Linnaeus Hammarby, Sweden. | Oil on canvas by Johan Henric Scheffel. Wikimedia Commons).

In this wedding portrait dated 1739, around the same decades as his provincial tours, Carl Linnaeus is seen wearing a formal, elegant, red collar-less coat, probably of fine broadcloth, with a matching waistcoat and a ruffled linen shirt. (Courtesy: Linnaeus Hammarby, Sweden. | Oil on canvas by Johan Henric Scheffel. Wikimedia Commons).Overall, in most of Linnaeus’ extant portraits, linen shirts are visible, just as the same was mentioned in a few journal notes during journeys. For instance, when travelling to Lapland in 1732, he listed ‘1 shirt and 2 pairs of half-sleeves’ among his possessions. His much later estate inventory of 1778 shows long lists of bed linen and clothing too. At his demise, his home owned, for instance: ’39 pieces of Damask [Table] Cloths, 286 pieces of Napkins, 3 pieces of Tea Cloths, 16 pairs of Unbleached Sheets, 17 pairs of Tow Cloth Sheets, 11 pieces of Pillowcases, 3 pieces fine Towels’. It is possible to conclude that observations of flax preparation and linen material were not only part of his botanical interest, but the increased growing of flax and the weaving of linen by the country’s manufacturers, as well as a handicraft in home interiors, were seen as most vital at the time to promote due to the advantages for the domestic economy of Sweden. Simultaneously, a well-to-do household like Linnaeus preferred to wear comfortable linen shirts, sleep between linen sheets, and own desirable damask table linen.

Sources:

- Bennet, Stephen, Directeuren Stephen Bennets Berättelse om lins planterande, beredande spinning, wäfnad och övriga tilberedning, Stockholm 1738.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets konst och kulturhistoria, Christinehof 1992.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 18-25, 286-292, 310-312 & for a full Bibliography and a wide selection of publications about 18th century linen manufacturing in Sweden, see this book).

- Kolthoff, Herman, Berättelse om de harlemske linne blekerierne, insänd til kongl. maj:ts och riksens commerciecollegium ifrån Amsterdam..., Stockholm 1738.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Utfärdade HallOrdning och Allmänne FactorieRätt. För alla Manufacturister uti Silke, Ull och Linne,... Stockholm 1739.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. They were published after the manuscript by Algot Hellbom, Sigurd Fries and Roger Jacobsson. vol. I., Umeå 2003.

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE