ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

FROM MARKET TO DEPARTMENT STORE

– The Selling of Textiles in Whitby from 1700 to 1914

Market Day has been Saturday in Whitby ever since the mid-15th century; until then, Sunday was the day for markets in the town. The present Market Place has been in use since 1640 and has consistently been the site of the market throughout the period from 1700 to 1914. This essay will look more closely at the trade in textiles and clothing in the open air within a small coastal town such as Whitby – in contrast to the indoor specialist family shops and larger drapery establishments. Research has been done via a wide selection of primary sources, including contemporary printed books, plans, censuses, preserved clothing, photographs and advertisements in the local newspaper.

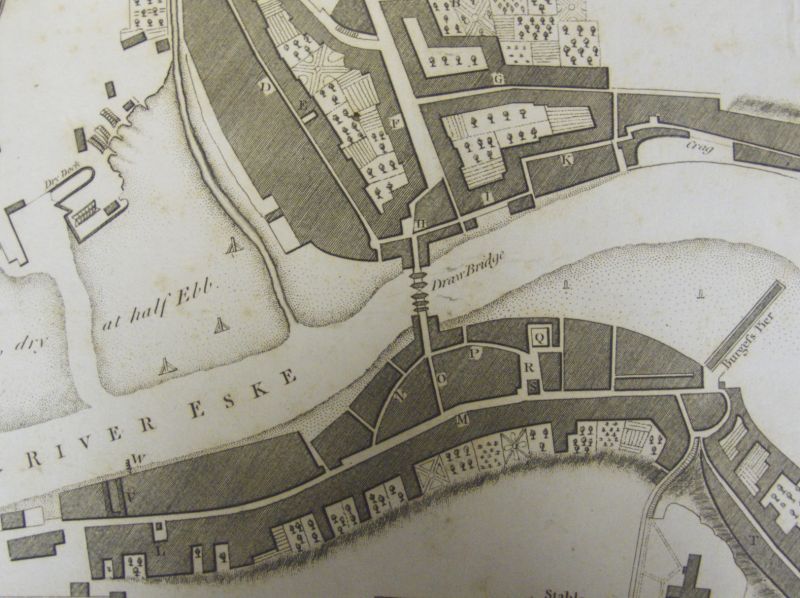

Detail of central Whitby during the 1770s, the streets of medieval origins gathered on each side of the ‘Draw Bridge’ and at this time many of the properties still had large gardens. ‘Plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby. Made in the Year 1778 by L. Charlton.’ The market place being marked with a “R” on the plan. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Plans and Views of Whitby 769.942.74).

Detail of central Whitby during the 1770s, the streets of medieval origins gathered on each side of the ‘Draw Bridge’ and at this time many of the properties still had large gardens. ‘Plan of the Town and Harbour of Whitby. Made in the Year 1778 by L. Charlton.’ The market place being marked with a “R” on the plan. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Plans and Views of Whitby 769.942.74).Acts of Parliament from as early as 1764, among other things, introduced new regulations about paving and keeping the streets and squares clean, which greatly increased outside trade. To quote: ‘Also it is enacted, That no person whatsoever shall erect or set out in the public streets, any table or stall for the sale of merchandise, save in the Market-Place, or on a market-day, under the penalty of forfeiting five shillings for every such offence.’ These new laws made it easier for the shops inside the town’s buildings to expand and diversify, since trading from open stalls now came under severe restrictions both to the times and places where business could be transacted. Probably, the open market and street stalls were able to offer a richer choice of textiles before that year, since until then, sellers would have had unrestricted opportunities to advertise their goods when and where they liked, but it has not been possible to prove this from the extant documents. There is even surprisingly little evidence of sales of textiles and textile raw materials in the Market Place. In other words, it is difficult to establish with any certainty which textile materials were sold at those regular weekly markets, but it can be assumed that demand must have centred on the most essential goods, such as among other things wool, yarn, knitted stockings, lace, basic material for interior decorating, second-hand clothes plus woollen and linen material by the yard. Cloth of various qualities was kept on rolls and in bundles and measured out by the seller with a yardstick – just as in shops – so that the customer could get the desired length of material for making clothes or interior decoration.

From Alison Adburgham’s research into Shops and Shopping 1800-1914, one may draw on a description of London markets in the 1820s for likely parallels with the sales of drapery for men in a smaller town like Whitby. ‘Stalls in open markets’, she writes, did a large part of the total men’s outfitting trade at that time, and also of the drapery trade in provincial cities and country towns.’ Almost exactly a hundred years later, we read in the 1911 Whitby census of a woman who must have sold her wares in the Market Place: ‘Hawker in Drapery, Ruth McGuire 49 years, Church street’; clearly someone who travelled about and sold her cloth or second-hand clothes, while habitually calling out tempting offers of what she had to sell. McGuire had been born in Gloucestershire, so it may have been only by chance that she happened to be selling her drapery in Whitby Market that day. Earlier censuses include no hawkers of textiles, though it may be that any such were simply included under the word ‘hawker’.

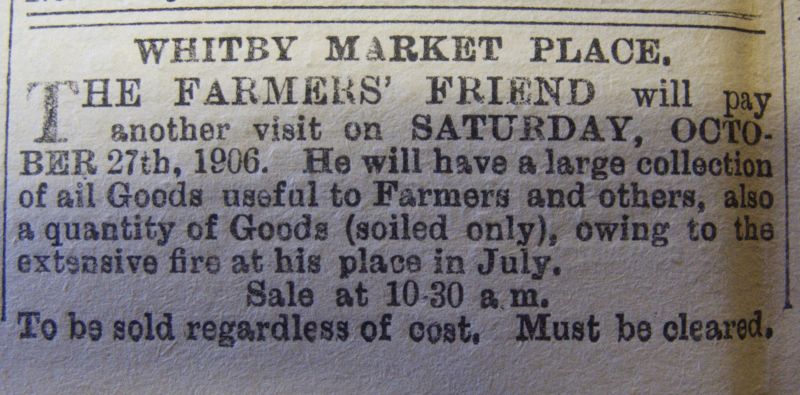

During the 1855-1914 period the Whitby Gazette hardly ever advertised anything at all for sale in the Market Place, perhaps because there was no need to encourage local people to go there on Saturdays. A rare exception was this short notice on Friday 19 October 1906 advertising ‘Whitby Market Place’. Even if this gives no information about what was for sale, it is extremely likely that various types of everyday textiles and clothes would have been available. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

During the 1855-1914 period the Whitby Gazette hardly ever advertised anything at all for sale in the Market Place, perhaps because there was no need to encourage local people to go there on Saturdays. A rare exception was this short notice on Friday 19 October 1906 advertising ‘Whitby Market Place’. Even if this gives no information about what was for sale, it is extremely likely that various types of everyday textiles and clothes would have been available. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

Photographs are another source of information about goods for sale on market days, but it is hard to distinguish any textiles for sale in the few photographs taken c.1880-1914 in Whitby Market Place. The majority of the products in the pictures seem to be food of all kinds, baskets, household wares and china. This particular picture was taken in the 1880s. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection. Photo: Frank Meadow Sutcliffe).

Photographs are another source of information about goods for sale on market days, but it is hard to distinguish any textiles for sale in the few photographs taken c.1880-1914 in Whitby Market Place. The majority of the products in the pictures seem to be food of all kinds, baskets, household wares and china. This particular picture was taken in the 1880s. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection. Photo: Frank Meadow Sutcliffe). Whilst a somewhat later photograph – circa 1920 – shows bedlinen and table-linen for sale, prominently displayed to the prospective buyer on a table together with folded textiles. This snapshot of everyday life on a summer day suggests that textiles are also likely to have been regularly displayed for sale in this way in the market square on Saturdays even before 1914 in Whitby. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, E 5450. Unknown photographer).

Whilst a somewhat later photograph – circa 1920 – shows bedlinen and table-linen for sale, prominently displayed to the prospective buyer on a table together with folded textiles. This snapshot of everyday life on a summer day suggests that textiles are also likely to have been regularly displayed for sale in this way in the market square on Saturdays even before 1914 in Whitby. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, E 5450. Unknown photographer). This photograph taken along Pier Road in the early 20th century however, is evidence that by now it must have been possible to set up stalls and sell goods elsewhere in the town than in the Market Place. A display of different breadths of lace has attracted the attention of a well-dressed lady with two small daughters at her side. It seems that this lace stall operated on this spot during the summer months during the Edwardian period and up to the outbreak of the First World War. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, W 4394. Unknown photographer).

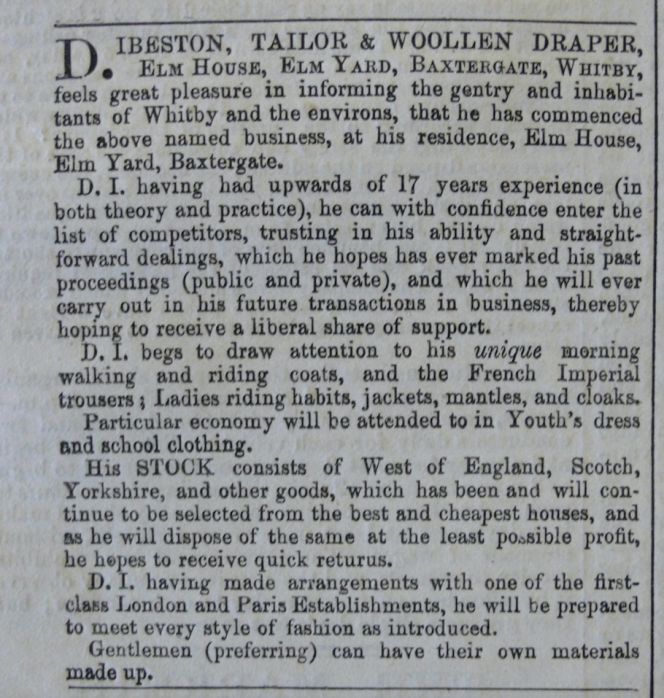

This photograph taken along Pier Road in the early 20th century however, is evidence that by now it must have been possible to set up stalls and sell goods elsewhere in the town than in the Market Place. A display of different breadths of lace has attracted the attention of a well-dressed lady with two small daughters at her side. It seems that this lace stall operated on this spot during the summer months during the Edwardian period and up to the outbreak of the First World War. (Courtesy of: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, W 4394. Unknown photographer).The market and shops existed side by side during the whole of this period and a long line of professional men and women with a variety of specialisations in the textile field were employed by these businesses. This branch of trade in Whitby is only hinted at here with a selection of examples of various types of shops advertised in the Whitby Gazette. For instance, in July 1855, the little shop ‘Berlin Room Top of Flowergate’ owned by Miss E. Clark sold every kind of embroidery material, yarns, baby clothes and accessories that the women of the town could want. That this shop had a somewhat hidden nature can be gathered from a sign with a pointing hand reading ‘Entrance up the Passage’. Whilst, an advertisement for D. Ibeston, Tailor and Woollen Draper (illustrated below) shows that this particular person carried on his business ‘... at his residence, Elm House, Elm Yard, Baxtergate’. It was still very common for business to be conducted at the same address as the owner’s home, even if this was not usually stated in these advertisements. Even in this case, the shop was not right on the main street. But advertisers in a small town like Whitby usually needed to give no more exact description of position and size, etc., since customers already knew the streets well and it was usually enough to provide the address. Thus, a tradesman might simply state ‘New Address’ without any more detailed information.

An 1865 advertisement from the local paper in which ‘D. Ibeston, Tailor and Woollen Draper’ wishes to inform prospective customers of his expertise as a tailor as well as future opportunities to offer his services from the business situated at his residence. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1865, May). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

An 1865 advertisement from the local paper in which ‘D. Ibeston, Tailor and Woollen Draper’ wishes to inform prospective customers of his expertise as a tailor as well as future opportunities to offer his services from the business situated at his residence. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1865, May). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.In general, shops were small at this time and usually specialised within a relatively narrow field, but a trend began during the last twenty years of the century for larger shops with more than one department. The sort of large multi-story department stores that sold everything under one roof from exclusive material, lace, parasols, gloves, hosiery and furs to tapestries, and also provided cleaning and drying services, a furniture store and tearooms, etc., which had begun to develop in larger towns and cities from the middle of the 19th century, were not to be found in a town like Whitby. But this trend did develop on a smaller scale, with advertisements telling eagerly of the many goods to be found in the various departments of the store. In other words, the idea was to give the customer the impression that everything he or she might need was available at that particular shop and that the firm was eager to satisfy the potential customer’s every possible wish.

James N. Clarkson & Son was one of the larger stores that frequently announced its extensive stock; for instance, in the spring of 1885, ‘We are now showing in all departments – Novelties for the Summer Season’ in the following six departments: ‘Silks, Dresses, Mantles & Jackets, Fancy Department, Millinery, and Dress-making’. Even the town’s smaller shops were anxious to advertise any enlargements of their premises; for example, ‘Robert Spanton, Hatter, Hosier and Shirt Maker’ wished to inform that he had ‘… Removed to the large and commodious Corner Premises, immediately opposite his Old Shop’. In the early 20th century more and more advertisements could be found from the larger towns in the neighbourhood. One often repeated example was ‘Middlesbrough’s Great Shopping Centre. Excelsior!’ which during the spring of 1909 took a full-page advertisement in the Whitby Gazette to describe in text and pictures everything that the fashion-conscious lady and her family could need and could buy at the best prices. Yet despite all these tempting department stores within a day’s journey by train, in 1914, there was still a good selection of shops of various sizes in Whitby able to satisfy the needs of local residents as well as the requirements of the many visiting tourists for clothes, hats, material and furnishing textiles. Everything from daily work clothes to fashionable, up-to-date luxury accessories for holiday-making summer visitors.

Sources:

- Adburgham, Alison, Shops and Shopping 1800-1914, London 1967 (quote p. 15).

- Charlton, Lionel, The history of Whitby and of Whitby Abbey, York 1779.

- Hallett, Anna, Markets and Marketplaces of Britain, Oxford 2009.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 40-44).

- Kendall, Hugh P., The streets of Whitby and their associations, Whitby 1971.

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1841-1901 microfilm & 1911 digital).

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Including Whitby Gazette 1855-1914, Plans and Views of Whitby & Acts of Parliament, George III, London 1764, p. 373).

- Whitby Museum, Photographic- & Costume Collections. Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Including research on a wide selection of photographs and clothing).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE