ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

FROM WOOL FIBRE TO CLOTH

– A mid-18th Century Case Study about Household and Manufacture Traditions

Discussions and proclamations were frequent on the subject of sheep wool in Sweden – as to which breeds were the most advantageous ones and how they could be cross-bred to achieve the best and softest wool in such a manner as at the same time would favour the country’s policy of self-sufficiency and minimise the need of imports. The large sheep estates, together with the ManufacturContoir of the Four Estates of the Realm, were the leading advocates for breeding from the imported stock and there were already in the country several foreign strains mixed with the domestic ones, something which was not always without its complications. This essay focuses on wool fibres and cloth samples from the Skåne province in 1751, registered and kept by the Board of Commerce. The preserved samples will be compared with journal observations by the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), from his journey in 1749 to the southernmost province, assisted by other contemporary printed decrees etc., revealing details of wool and cloth in this geographical context.

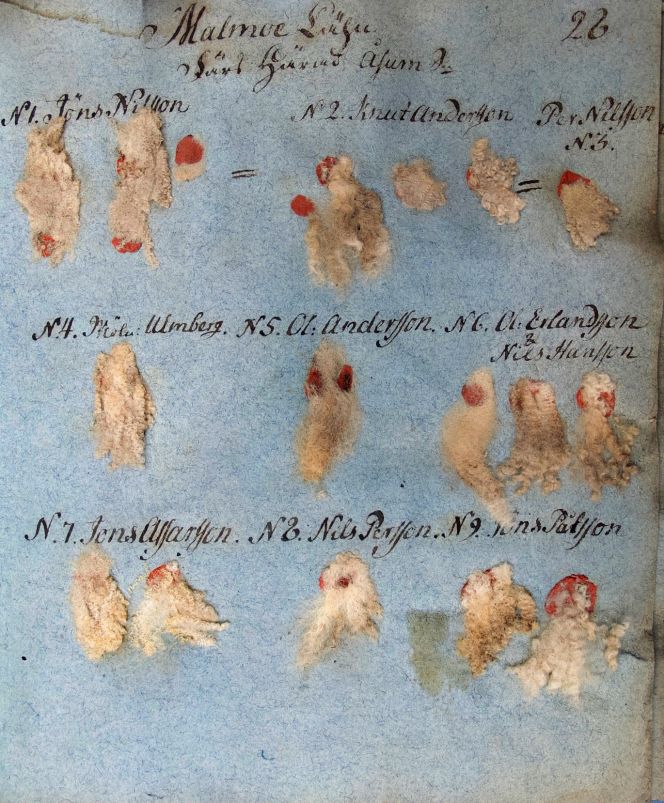

Example of award-winning wool fibres among nine peasant farmers in the district of Färs, in the parish of Åsum in southernmost Sweden. The extant Board of Commerce document regarding Skåne – ‘Malmoe Lähn’ (county of Malmö) and ‘Christianstads Lähn’ (county of Kristianstad) – shows award-winning qualities with a seal and woven samples from the province, spread over 41 pages. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 28). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Example of award-winning wool fibres among nine peasant farmers in the district of Färs, in the parish of Åsum in southernmost Sweden. The extant Board of Commerce document regarding Skåne – ‘Malmoe Lähn’ (county of Malmö) and ‘Christianstads Lähn’ (county of Kristianstad) – shows award-winning qualities with a seal and woven samples from the province, spread over 41 pages. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 28). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Wool was the most important spinning material for clothes and other textiles for keeping warm during the 18th century; no material could warm as wool, and that is a reality that can be traced a long way back in history. In addition, the material is regarded as humanity’s oldest spinning material and the reason for that, besides the warming properties, was probably the ease and simplicity of preparing wool as compared to the complex methods of hemp and flax. The popularity of wool is also due to its varied areas of use for anything from the thinnest conceivable gauze-like fabrics, fine broadcloth to coarse wadmal, knitted garments, felting, decorative embroidery, woven textiles for interior furnishings or upholstery etc. In the early decades of the 18th century, Sweden as a country did import substantial quantities of wool fibre and woollen cloth, but just as was the case with flax and hemp, the inhabitants of the country were also encouraged through the Hat Party’s policy to buy sheep either to process the wool further themselves or sell it on to the manufactures. In contrast to the handicraft taking place all over the country for everyone’s needs, textile manufacturers in towns and cities hallmarked their produce – with a stamp of authenticity – and had to follow the rules and regulations linked to their trade. Sheep breeding was also disseminated across all layers of society, from the large sheep-breeding farms/estates to the poorest crofter. On his provincial tours, the naturalist Carl Linnaeus repeatedly recorded noteworthy events to do with sheep breeding and wool, whereas notes on the more everyday occurrences of handling wool and sheep are rare.

The parliament of 1741 also presented plans for how the farmers would be rewarded and encouraged to improve and renew their stock of sheep. That formed one of many decisions taken by the political leaders, who after that were informed via enlightening “small prints” about new regulations, bans, and news for the benefit of the country’s inhabitants. The farmers were not, however, so easily convinced about novelties, their old traditions of how to process wool fibres being deeply rooted in the countryside. The new softer kinds required a different and more cautious handling, and Jonas Alström (1685-1761) of the manufacturing mill at Alingsås in Västergötland province spearheaded the development of the new knowledge. He was of the opinion that trainees should be trained at the mills and large sheep farms so as later to be able to instruct the country folk in the best ways of washing, sorting, carding and spinning the wool.

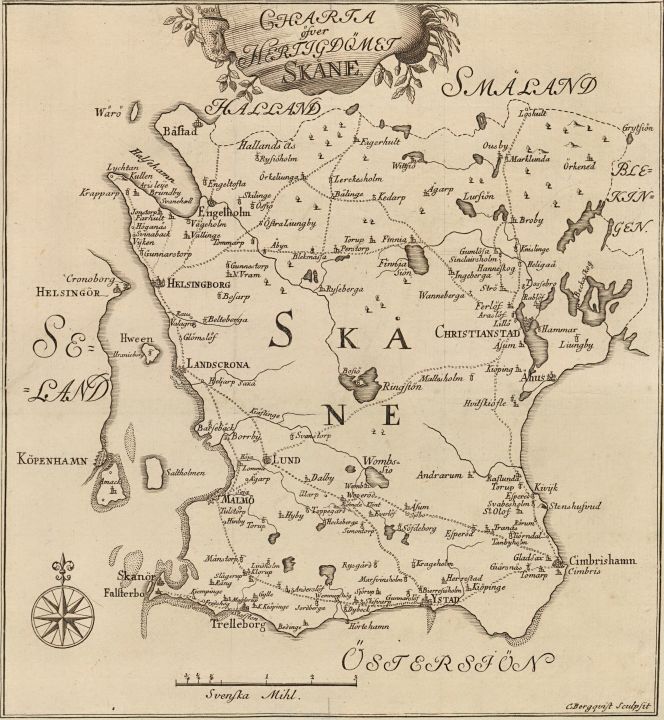

This map, included in Carl Linnaeus’ journal of the journey to Skåne in 1749, was assisted by dotted lines for his travel route, which is helpful for research linked to his observations – sheep and their wool being one such perspective. Traditions varied as to the shearing of the sheep: shearing both in the autumn and the spring, in the autumn only, in the spring only, shearing using clippers, stripping the wool or washing the sheep before shearing. Linnaeus encountered a number of those methods on his tours of Skåne as well as on the earlier journeys during the same decade to the provinces of Öland, Gotland and Västergötland. At the Sinclairsholm estate – marked out on the map and situated in the northeast corner of Skåne – it was, for instance, noted on 18th May 1749 that the Spanish sheep ‘must not be shorn more than once a year, for against the winter they do not tolerate the cold.’ Linnaeus also observed the foreign breeds of sheep in the province’s countryside, where it was similarly evident that the sheep did not survive the winter without a good layer of wool. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa…1751, XIV – 1).

This map, included in Carl Linnaeus’ journal of the journey to Skåne in 1749, was assisted by dotted lines for his travel route, which is helpful for research linked to his observations – sheep and their wool being one such perspective. Traditions varied as to the shearing of the sheep: shearing both in the autumn and the spring, in the autumn only, in the spring only, shearing using clippers, stripping the wool or washing the sheep before shearing. Linnaeus encountered a number of those methods on his tours of Skåne as well as on the earlier journeys during the same decade to the provinces of Öland, Gotland and Västergötland. At the Sinclairsholm estate – marked out on the map and situated in the northeast corner of Skåne – it was, for instance, noted on 18th May 1749 that the Spanish sheep ‘must not be shorn more than once a year, for against the winter they do not tolerate the cold.’ Linnaeus also observed the foreign breeds of sheep in the province’s countryside, where it was similarly evident that the sheep did not survive the winter without a good layer of wool. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa…1751, XIV – 1).According to the late historian Sven T Kjellberg’s in-depth studies of wool, the importance and advantages of the wool from the Swedish native breed of sheep for coarser woollen textiles had not been fully appreciated by the Board of Commerce until the early 1830s, by which time the domestic wool had changed through breeding and crossing with foreign breeds to the point of being unrecognisable. That was one development for which Carl Linnaeus, among others, had been an advocate in his day nearly 100 years earlier, thanks to the newly gained popularity of the English and Spanish breeds, which yielded wool so much softer than the domestic sheep’s coarse equivalent. For the best potential for the country’s manufacture and sheep farming, he kept talking about those foreign breeds, which should preferably be separated from the other animals. On his journey to the province of Skåne, for example, he wrote on 2nd June 1749: ‘The sheep wandered in the fields near Cimbrishamn (marked out on the map and situated in the southeast corner of the province) almost in greater multitude than I have seen in any other place, and they were both of better and worse kind. The town of Cimbrishamn alone had 500 old sheep and 500 young ones and a few English rams. Gladsax, on the other hand, had even more sheep and several English rams.’

Just as there were awards to encourage foreign sheep breeds, so there were similar schemes for spinning. Knowing how to handle the spinning wheel and produce a fine and even yarn was considered one of a woman’s most essential skills. The most skilful women spinners were honoured with a medal, instituted by King Adolf Fredrik and Queen Lovisa Ulrika in 1751 – whose portraits adorn the reverse side of the medal – with the text ‘To the Honour of the woman who knows how to do fine and fast spinning.’ (Private ownership).

Just as there were awards to encourage foreign sheep breeds, so there were similar schemes for spinning. Knowing how to handle the spinning wheel and produce a fine and even yarn was considered one of a woman’s most essential skills. The most skilful women spinners were honoured with a medal, instituted by King Adolf Fredrik and Queen Lovisa Ulrika in 1751 – whose portraits adorn the reverse side of the medal – with the text ‘To the Honour of the woman who knows how to do fine and fast spinning.’ (Private ownership).Spinning was also very much seen as a child’s work, something which Linnaeus strongly advocated, as did his other contemporaries. It was regarded as self-evident that children from the age of seven or eight should contribute to the livelihood of the peasantry and the poorer section of the people. In Malmö, ‘such a nice institution for poor children’ (12th July 1749) existed – where sewing, spinning and bobbin lace were taught. There was also a clothing factory in the city, as in many other places in the country, as there were good prospects for such activities to expand at the time. That was due to the political directives on a self-sufficient clothing trade, which placed completely new requirements on the quantity of yarn that had to be produced to cover the country’s needs.

Linnaeus showed a great interest in the largest broadcloth manufacturer of the town when he visited Malmö on 18th June 1749, where mainly ‘fine broadcloth, swanboy [thick, soft], rask [thin and smooth], camlet, plush [often with flower designs], felt, flannel, shag or nap, Freisian or fearnought, so-called molton [tightly woven, soft and thick]’, in other words, woollen fabrics of varying quality and thickness. He described the activity as follows: ‘... established by Mr Mayor [Josias] Hegardt, consisted of 5 rough looms and 2 finer ones, besides the ones belonging to the son, Johan Hegardt, who had 3 rough looms, 2 cloth looms and 2 stocking looms. Here I saw more wool than ever I had seen in any one place. Many a man goes dressed in fine broadcloth, who would never dream of the number of processes the wool goes through before it can become a garment.’ Furthermore, it was noted there that the production required thirty-seven different stages, from the shearing of the sheep to the making up of the garments. At the time of his visit, the manufacturer was at its peak with 113 employees, most of whom were ‘scrubbers, carders and spinners’ who numbered 74. Other occupational categories consisted of ‘4 masters, 5 journeymen, 9 apprentices, 2 sorters and washers of wool and 1 feller with 2 help-mates, 1 cutter with a journeyman and 1 help-mate, 2 burlers and 2 dyers’. A book of samples (1744) with manufacture-woven fabrics is still kept at The National Archive, including, among many Swedish manufacturers, a large number of broadcloth qualities in different colours by Josias Hegardt of Malmö. The fabrics from that enterprise were divided into categories of differing quality and price; there it shows the most common thickness as named 9/4, the finest 11/4 and the coarsest 7/4. Other manufacturers in Malmö in the year 1749 were: J Falkenbladh, who made ‘wool, stuff, sweaters and stockings’ and N Suell, who produced felt caps. That the weaving and knitting of stockings were linked to many manufacturers in the country was not recorded by Linnaeus, though, except for Johan Hegardt’s ‘2 stocking looms’ (Kjellberg: p. 737).

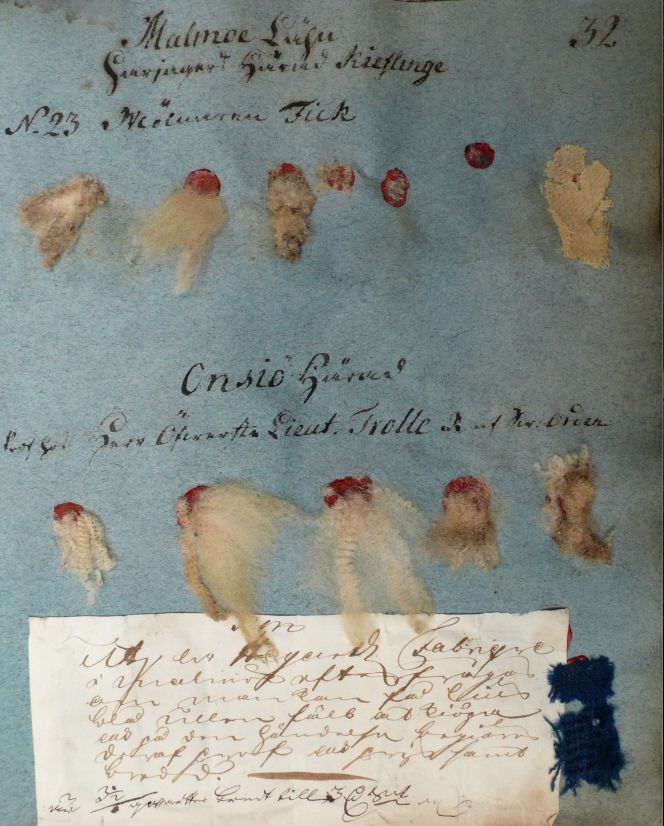

In conclusion, two additional pages of the total of 41 pages from the award-winning wool fibres with a seal and woven samples from the province in 1751 will exemplify the importance of good qualities for individual sheep owners as well as the estates of the nobility to be able to deliver to broadcloth manufacturers in towns and cities.

These samples of award-winning wool fibre originated from two sheep owners in ‘Malmoe Lähn’ in Skåne province. On top, a miller named Fick in Harjager district, from which wool the earlier mentioned Hegardt manufacture in Malmö had produced a white twill woollen quality, sampled to the right. The same woollen manufacturer had also woven blue broadcloth sampled below from the sheep owned by a lieutenant colonel and nobleman Trolle in the Onsjö district. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 32). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

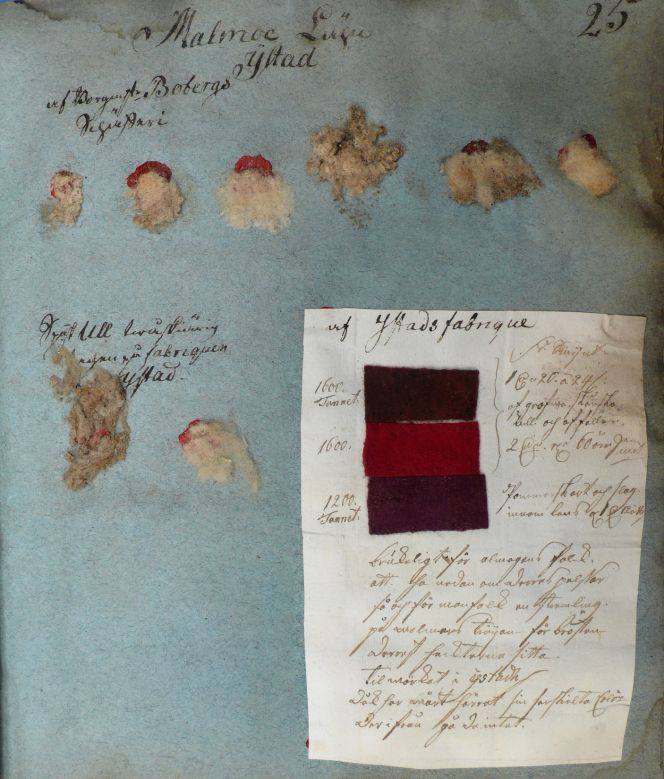

These samples of award-winning wool fibre originated from two sheep owners in ‘Malmoe Lähn’ in Skåne province. On top, a miller named Fick in Harjager district, from which wool the earlier mentioned Hegardt manufacture in Malmö had produced a white twill woollen quality, sampled to the right. The same woollen manufacturer had also woven blue broadcloth sampled below from the sheep owned by a lieutenant colonel and nobleman Trolle in the Onsjö district. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 32). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Whilst this single page of award-winning samples in the Board of Commerce document originated from Ystad, a town on the south coast of Skåne (also visited by Carl Linnaeus in 1749 and marked on his map above). The fine wool fibre samples were noted to be from ‘Mayor Boberg’s sheep-breeding farm’. The local' Ystad Manufacture' had also used these particular wool consignments to weave broadcloth – dyed in the three reddish colours attached here. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 25). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Whilst this single page of award-winning samples in the Board of Commerce document originated from Ystad, a town on the south coast of Skåne (also visited by Carl Linnaeus in 1749 and marked on his map above). The fine wool fibre samples were noted to be from ‘Mayor Boberg’s sheep-breeding farm’. The local' Ystad Manufacture' had also used these particular wool consignments to weave broadcloth – dyed in the three reddish colours attached here. (Collection: The National Archive…1751, p. 25). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 294-302 & 312. For a complete Bibliography and a wide selection of publications about 18th Century wool production and woollen manufacturing in Sweden, see this book).

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Förordning Angående Premier för god Swensk Ull ..., Stockholm 1751.

- Kongl. Maj:ts och Riksens CommerceCollegii Kungörelse, Angående The til Inrikes Ull Handelens befrämjande..., Stockholm 1757.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Utfärdade HallOrdning och Allmänne FactorieRätt. För alla Manufacturister uti Silke, Ull och Linne,... Stockholm 1739.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm, Sweden. (1751: Kommerskollegium, Kammar-kontoret Ullprover. & ‘Industrivävnadsprover A-Ö Provbok med tyger: 1744’ & ‘Riksdagens utskottshandlingar 1740-41 vol 28: handels och manufakturdeputationens betänkande ang. gott fårslags utspridande bland allmogen 7/3 1741’). | Research visits in February 2014.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE