ESSAYS No: XXXII | March 1, 2015 | By Viveka Hansen

This sixth historical essay from North America will focus on the Finnish/Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm’s studies of the fur trade throughout his stay and travels in the colonies from 1748 to 1751, together with a brief discussion of the well-documented trades’ long and complex history. His journeys by foot, horse, coach and boat passed through the present-day Province of Quebec in Canada and the U.S. states of Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware and New Jersey. The aim of this text is to present this lucrative trade from the eyes of Kalm through journals, followed up with my observations learned from the research project – “Bridge Builder Expedition – North America” – in the summer of 2014.

Tadoussac was one of the centres for fur trade between the French and the First Nation’s people during the 17th and 18th centuries – by which it was already an established trading post with a long history. Here a view over the all important road of trade – Saint Lawrence River – and Petite Chapelle de Tadoussace (Tadoussac Chapel) built 1747, just a few years before Kalm visited areas close-by. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Even if Pehr Kalm never visited Tadoussac, he does mention it on numerous occasions in his journal (1749). This location was primarily denoted in connection to the fur trade and among these observations he wrote in both English and French from Tadoussac: ‘White foxes from Tadoussac, renards blancs de Tadoussac.’ Pelts from foxes, as well as many other mammals, had long before the Europeans arrived on the northeast coast of America been valuable and necessary trading goods for the Native Americans. In addition, the Europeans’ 16th to 18th century fashions, desires or needs for furs in various clothing increased the demand manifold.

![This portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) is probably depicting the French diplomat Charles de Solier in London 1534 [print 1647], dressed in a fur-edged mantle. If the wealthy man’s fur details had its origin from the earliest fur-trading via Jacques Cartier’s first voyages into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the 1530s, is not possible to verify. But this portrait – together with many other contemporary depictions – is proof of the trades future potential while at this time was already an established fashion in well off circles to use fur in linings, edgings etc on clothing to keep warm – especially on the British Isles and in Northern Europe. Courtesy of: Folger Shakespeare Library, Digital Image Collection (38106).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-038106-664x867.jpg)

This portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) is probably depicting the French diplomat Charles de Solier in London 1534 [print 1647], dressed in a fur-edged mantle. If the wealthy man’s fur details had its origin from the earliest fur-trading via Jacques Cartier’s first voyages into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the 1530s, is not possible to verify. But this portrait – together with many other contemporary depictions – is proof of the trades future potential while at this time was already an established fashion in well off circles to use fur in linings, edgings etc on clothing to keep warm – especially on the British Isles and in Northern Europe. Courtesy of: Folger Shakespeare Library, Digital Image Collection (38106).

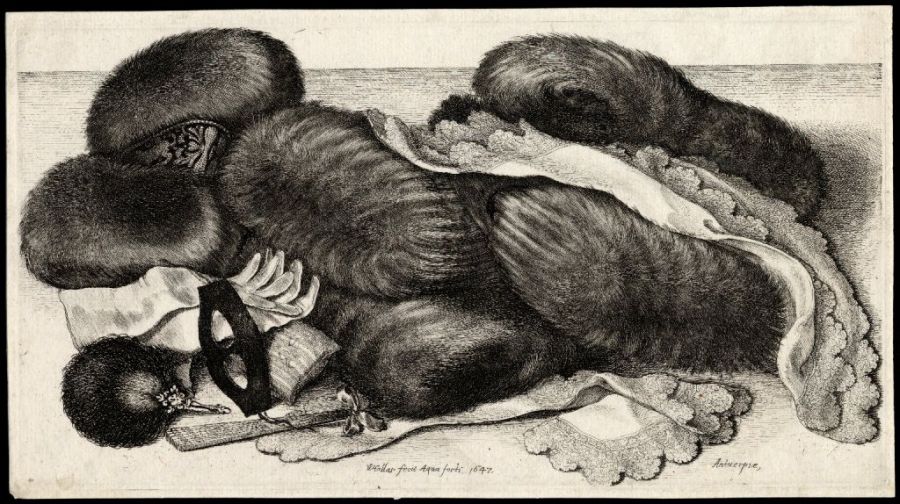

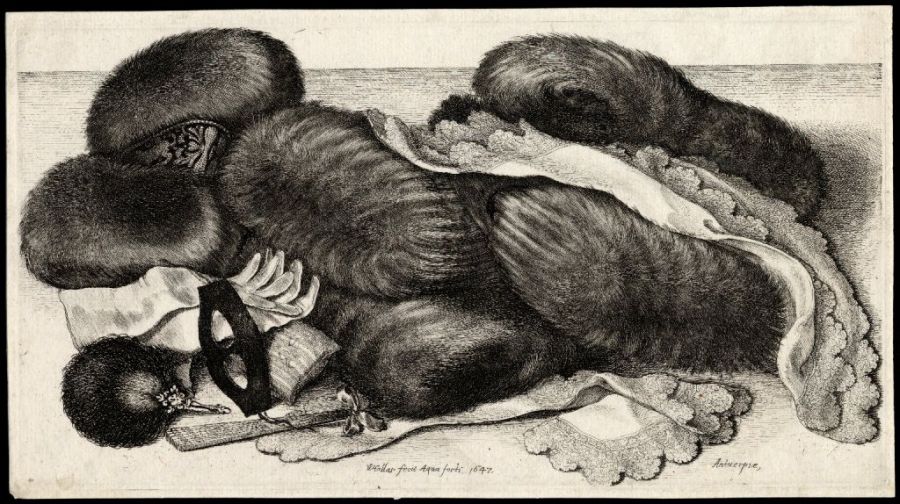

‘A group of muffs and articles of dress on a table’, etching dating 1647. This depiction demonstrates fashion accessories more than a hundred years later, showing how important fur continued to be for fashion conscious men and women during wintertime in Europe. Courtesy of: Folger Shakespeare Library, Digital Image Collection (6101).

The great popularity and status of using furs in clothing during the 16th and 17th centuries was not only in demand because of the cold weather; its wearers were also dependent on the complex trade and regulations for different groups in society. Jane Ashelford describes these facts in her book The Art of Dress: ‘In the early Tudor period furs had been the chief symbol of rank and wealth and, as such, were strictly governed by sumptuary legislation’ (p. 50). But she also mentions that these laws were not effective and problems also arose in both Britain and other northern European countries, due to that many animals were hunted to near extinction for their valuable skins.

The continuous great demand for skins and fur garments in Europe, of course, made the North American market even more precious and important for the French and English traders during a period of several hundred years. Kalm’s observations in the late 1740s are, in this case, a most informative primary source with detailed descriptions from this period of the trade, including all types of animal fur/skins used for linings, accessories on clothes, muffs, fur coats, etc. Primarily for the European market, but also for the growing populations in the North American colonies along the east coast.

The beaver was repeatedly mentioned in Kalm’s journal for its valuable skins, on one such occasion when he studied an old Boston newspaper during one of his stays in Philadelphia (7th Dec., 1749). To document the trade he copied a Price List from ‘The American Weekly Mercury’ listing goods for sale in Boston on the 23rd February in 1720. Among various items for sale – the Bostonians could buy ‘Beaver skins’ for ‘3 sh. 10 d. p. pound’. Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum: ‘American Beaver’ by John James Audubon c. 1844.

Beaver hats were in fashion in a variation of models over an extended period of time, for around 300 years starting from circa 1550. These hats made of felted beaver fur had a combination of desirable qualities: durability, softness, and beautiful material. Overall, they were rainproof. Reasons making it an essential part of the fur traders’ business, but it was not only beaver pelts included in this long-lived commerce, which Kalm’s detailed accounts give many examples of from the mid 18th century.

The following citations from his journal will show us various impressions of the fur trade and the importance it had for the French, English as well as the Native Americans. Smuggling, privileges, geographical understanding of local areas and historical knowledge of the lucrative trade are also significant. On 13th June in 1749, he noticed, for example, when arriving in Albany: ‘All the yachts which ply between Albany and New York, belong to Albany. They go up and down the river Hudson, as long as it is open and free from ice. They bring from Albany boards or planks, and all sorts of timber, flour, peas, and furs, which they get from the Indians, or which are smuggled from the French.’

Still in Albany one week later (June 21, 1749), he wrote: ‘There is a great penalty in Canada for carrying furs to the English, that trade belonging to the French West India Company; notwithstanding which the French merchants in Canada carry on a considerable smuggling trade. They send their furs, by means of the Indians, to their correspondents at Albany, who purchase it at the price which they have fixed upon with the French merchants. The Indians take in return several kinds of cloth, and other goods, which may be got here at a lower rate than those which are sent to Canada from France.’

Two months later, in the French colony (August 6, 1749, Quebec), Kalm was studying the fur trade even closer: ‘The French merchants from Montreal on their side, after making a six months stay among several Indian nations, in order to purchase skins of beasts and furs, return about the end of August, and go down to Quebec in September or October, in order to sell their goods there. The privilege of selling the imported goods, it is said, has vastly enriched the merchants of Quebec…’.

Further, two months later (October 5, Montreal), he also added some facts about the strict rules of the trade in the French area: ‘The beaver trade belongs solely to the Indian company in France, and nobody is allowed to carry it on here, besides the people appointed by that company. Every other fur trade is open to everybody. There are several places among the Indians far in the country, where the French have stores of their goods; and these places they call les postes.

The widespread importance of the fur trade can additionally be understood from these unique extensive lists, as Kalm recorded in his journal during a stay in Montreal on 22nd September 1749.

‘The prices of the skins in Canada, in the year 1749, were communicated to me by M. de Couagne, a merchant at Montreal, with whom I lodged. They were as follows:

- Great and middle sized bear skins, cost five livres.

- Skins of young bears, fifty sols.

- ~~~~ lynxes, 25 sols.

- ~~~~ pichoux du sud, 35 sols.

- ~~~~ foxes from the southern parts, 35 sols.

- ~~~~ otters, 5 livres.

- ~~~~ racoons, 5 livres.

- ~~~~ martens, 45 sols.

- ~~~~ wolf-lynxes, 4 livres.

- ~~~~ wolves, 40 sols.

- ~~~~ carcajoux, an animal which I do not know, 5 livres.

- Skins of visons, a kind of martens, which live in the water, 25 sols.

- Raw skins of elks, 10 livres.

- ~~~~ stags.

- Bad skins of elks and stags, 3 livres.

- Skins of roebucks, 25, or 30 sols.

- ~~~~ red foxes, 3 livres.

- ~~~~ beavers, 3 livres.

I will now insert a list of all the different kinds of skins, which are to be got in Canada, and which are sent from thence to Europe. I got it from one of the greatest merchants in Montreal. They are as follows:

- Prepared roebuck skins, chevreuils passés.

- Unprepared ditto, chevreuils verts.

- Tanned ditto, chevreuils tanés.

- Bears, ours.

- Young bears, oursons.

- Otters, loutres.

- Pecans.

- Cats, chats.

- Wolves, loup de bois.

- Lynxes, loups cerviers.

- North pichoux, pichoux du nord.

- South pichoux, pichoux du sud.

- Red foxes, renards rouges.

- Cross foxes, renards croisés.

- Black foxes, renards noirs.

- Grey foxes, renards argentés.

- Southern, or Virginian foxes, renards du sud où de Virginie.

- White foxes, from Tadoussac, renards blancs de Tadoussac.

- Martens, martres.

- Visons, or foutreaux.

- Black squirrels, ecureuils noirs.

- Raw stags skins, cerfs verts.

- Prepared ditto, cerfs passés.

- Raw elks skins, originals verts.

- Prepared ditto, originals passées.

- Rein-deer skins, cariboux.

- Raw hinds skins, biches verts.

- Prepared ditto, biches passées.

- Carcajoux.

- Musk rats, rats musques.

- Fat winter beavers, castors gras d’hiver.

- Ditto summer beavers, castors gras d’été.

- Dry winter beavers, castors secs d’hiver.

- Ditto summer beavers, castors secs d’été.

- Old winter beavers, castors veiux d’hiver.

- Ditto summer beavers, castors vieux d’été.’

Even if Kalm predominately mentioned the fur trade from the French province of Quebec and the English areas of New York and Albany, he, on several occasions, also observed when people living in Pennsylvania were making use of skins/furs for their own use in clothing or to be sold in the nearest town. Two examples from 1748 and 1749: ‘Some people reckon squirrel flesh a great dainty, but they generally make no account of it. The skin is good for little, yet small straps are sometimes made of it, as it is very tough: others use it as a fur lining, for want of a better. Ladies shoes are likewise sometimes made of it.’ (Pennsylvania, near Germantown, November 14, 1748). The following year: ‘The skin sold for eighteen-pence, at Philadelphia. I was told that the Raccoons were not near so numerous as they were formerly, yet in the more inland parts they were abundant. I have mentioned the use which the hatters make of their furs…’ (Raccoon, Pennsylvania, February 8, 1749).

Even earlier historic trade with fur by Swedes in Pennsylvania caught Kalm’s attention (in Wallenius’ Extracts from Kalm’s Diary). Among several observations, he makes it clear that these types of furs were both valuable and in great demand in 1714: ‘In the same year, as Mr Björck was leaving, the Swedes sent along with him 115 furs, some of raccoons, others of mink, lynxes, otters, panthers and wild cats, some to the King of Sweden, others to Bishop Svedberg. Those of the King, which were dispatched to Pomerania, were seized by the enemy when Stralsund was lost (ibidem).’

Another common way of trading was via bartering, which an exhibition at the Art and Albany Heritage Area Visitor Center explains. The beaver, raccoon and doe skins’ values in 1765 were for example, compared as follows:

- One blanket = two middling beaver skins

- One small keg of rum = three large beaver skins

- One looking glass = two middle-sized raccoon skins

- One silk handkerchief = two good doe skins

- One beaver trap = two beaver skins, middle-sized

The bartering of fur and skins between the Iroquois and the early 17th and 18th century Dutch and later English settlers in the Beverwijck/Albany area – along the Hudson River – was of great significance. Particularly the beaver pelts, which became a cornerstone in the local economy and made the community grow and become more prosperous. The number of furs traded/bartered in the area reached its peak in 1656 (40,000 pelts), almost 100 years before Kalm’s visit to the town.

Sources:

- Albany Institute of History & Art and Albany Heritage Area Visitor Center, New York, U.S. (visits in the summer of 2014, “Bridge Builder Expeditions…”).

- Ashelford, Jane, The Art of Dress – Clothes and Society 1500-1914, London 2002.

- Brooklyn Museum; Online Collection – John James Audubon (American Beaver).

- Folger Shakespeare Library, Digital Image Collection.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes (Vol. Three Book 1 & 2, Pehr Kalm’s Journal). London & Whitby 2007-2012.

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Kalm, Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland. Helsingfors 1956.

- Musei de La Place-Royal, Quebec, Canada (visit in the summer of 2014, “Bridge Builder Expeditions…”).

- Musee l’Archeology & l’History, Montreal, Canada (visit in the summer of 2014, “Bridge Builder Expeditions…”).

- The IK Foundation; “Bridge Builder Expeditions – North America”.

- The Poste de traite Chauvin historical museum [Fur Trading Post], Tadoussac, Canada (visit in the summer of 2014, “Bridge Builder Expeditions…”).

More in Books & Art:

Today it is possible to experience and take in part of the trading post’s history through a 1960s replica which acts as ‘The Poste de traite Chauvin historical museum’ and is situated close to where Pierre de Chauvin’s original trading post was located, which dated from 1600. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Today it is possible to experience and take in part of the trading post’s history through a 1960s replica which acts as ‘The Poste de traite Chauvin historical museum’ and is situated close to where Pierre de Chauvin’s original trading post was located, which dated from 1600. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

![This portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543) is probably depicting the French diplomat Charles de Solier in London 1534 [print 1647], dressed in a fur-edged mantle. If the wealthy man’s fur details had its origin from the earliest fur-trading via Jacques Cartier’s first voyages into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the 1530s, is not possible to verify. But this portrait – together with many other contemporary depictions – is proof of the trades future potential while at this time was already an established fashion in well off circles to use fur in linings, edgings etc on clothing to keep warm – especially on the British Isles and in Northern Europe. Courtesy of: Folger Shakespeare Library, Digital Image Collection (38106).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-038106-664x867.jpg)