ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

GILBERT WHITE AND HIS NETWORK

– An 18th Century Case Study of Natural History and Textiles

As expected in The Natural History of Selborne, the naturalist Gilbert White (1720-1793) reveals little about his life, clothing, fabric purchases, or traditional textile craft. However, to know more about such matters, various correspondence, receipts, and other traces from his lifetime add further thoughts. This essay will look closer into this relatively unknown part of White’s observations and experiences, together with his connections to the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and a few of his former students. It is to be illustrated with artworks, correspondence, and original handwritten pages of White’s work, aiming to increase knowledge of his domestic sphere intertwined with learned natural knowledge seen from the perspective of a restricted geographical area in southernmost England.

An ink and pen portrait of Gilbert White as a young man was presented to him by a friend at White’s graduation at Oxford University circa 1746. He was depicted in the voluminous collarless clerical-type gown according to the dress code of his Master’s degree. On top of his wig, the square academic cap was worn, and around the neck, what seemed to be a black ribbon. (Courtesy: Gilbert White Museum and the Oates Collection).

An ink and pen portrait of Gilbert White as a young man was presented to him by a friend at White’s graduation at Oxford University circa 1746. He was depicted in the voluminous collarless clerical-type gown according to the dress code of his Master’s degree. On top of his wig, the square academic cap was worn, and around the neck, what seemed to be a black ribbon. (Courtesy: Gilbert White Museum and the Oates Collection).Overall, Gilbert White has been much written about in all sorts of research over the years, and general events of his life will not be repeated here but instead be randomly glanced at from several periods of his life. First and foremost, his only book, The Natural History of Selborne, which describes the local nature over almost twenty years, was written in two series of letters (some never posted) in the 1770s and 1780s addressed to the naturalist Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) and the lawyer-cum-naturalist Daines Barrington (1727-1800) together with other of White’s notes. The book has been published in many editions since the first edition in 1789, and his close methods of observing nature later influenced Charles Darwin (1809-1882), among many others.

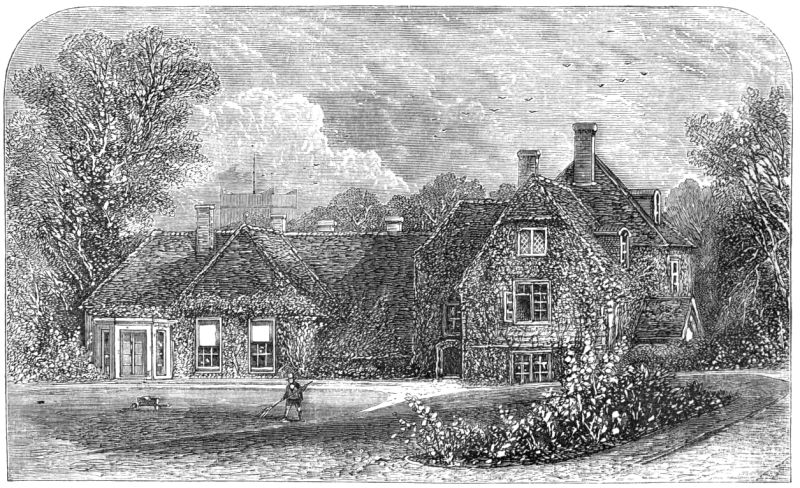

The family house, named ‘The Wakes’ in Selborne, England – where Gilbert White lived during parts of his childhood. A property to which White moved back after his father’s death in 1758 and lived for the rest of his life until he died in 1793. The house is kept as a museum today, and it has been restored and furnished with contemporary furniture from White’s lifetime, among many objects, including embroidered bed hangings made up for him by his four aunts. (This later engraving was originally published in the magazine ‘Once a Week’, vol. 8, p. 26, on 27 December 1862).

The family house, named ‘The Wakes’ in Selborne, England – where Gilbert White lived during parts of his childhood. A property to which White moved back after his father’s death in 1758 and lived for the rest of his life until he died in 1793. The house is kept as a museum today, and it has been restored and furnished with contemporary furniture from White’s lifetime, among many objects, including embroidered bed hangings made up for him by his four aunts. (This later engraving was originally published in the magazine ‘Once a Week’, vol. 8, p. 26, on 27 December 1862).Another detail of textile material culture can be gleaned from an Account Book, dated 1752-53, kept during Gilbert White’s time in Oxford. This manuscript has been studied by White’s biographer Richard Mabey, who found out that at the end of the year 1752, it was summed up that White paid for purchased fabrics in Mrs Croke’s haberdashery for £36.15s or almost a third of his proctorial earnings. These fabric qualities included: ‘official velvet sleeves and silk trimmings, for suits and waistcoats’ and ’20 yards of blue check’d linen for curtains.’ This seems to be a rare insight into his purchases of textile materials for clothing and household furnishing.

Like many church men in the 18th century, though, Gilbert White had developed a combined work role over the decades as a curate-cum-naturalist. Meaning that he had knowledge of Carl Linnaeus’ work and followed his classification system in botany and zoology – the two men, however, appear not to have had any correspondence but had several mutual contacts in the wide-stretching naturalist network of the time. Even if White followed strict classification rules, his written works were vividly described and regarded as a pleasant and interesting read about a small geographical area.

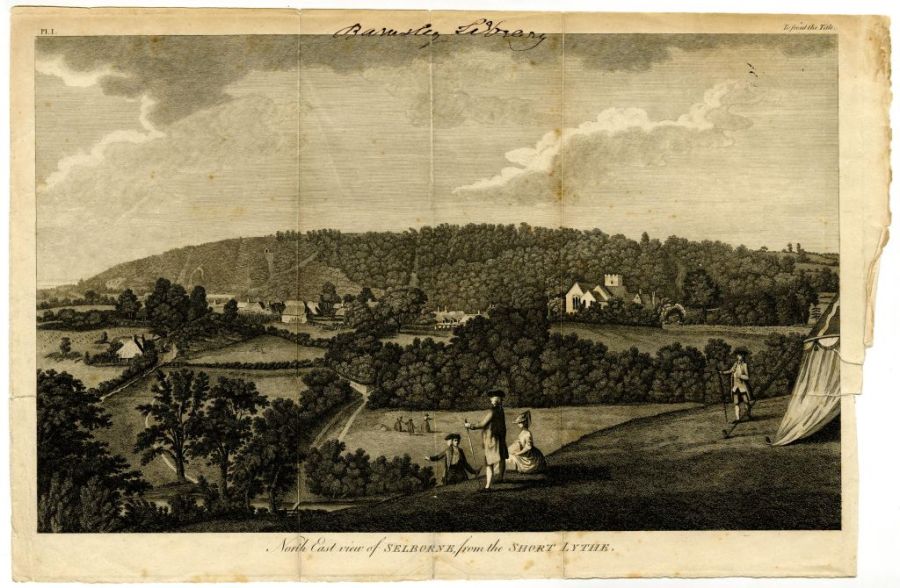

Gilbert White very much emphasised the importance of having a good understanding of all matters in such a small area – like Selborne, from his point of view – to give a complete picture of nature in this place. Preferably to study each and every creature in its natural environment. He believed that other writers should do the same in their local areas, which would give linked networks of extensive information for humanity over time. | This illustration was included in his ‘Natural History of Selborne’ 1789, where a group of well-to-do men and a woman – in typical fashionable clothes of the time – admiring the beautiful view over the small village. They were assisted by a sturdy, embellished linen tent for refreshments and protection from the sun on this summer’s day, contrasting with a group of fieldworkers in working dress in the valley. (Courtesy: The Trustees of the British Museum. No: 16113661303).

Gilbert White very much emphasised the importance of having a good understanding of all matters in such a small area – like Selborne, from his point of view – to give a complete picture of nature in this place. Preferably to study each and every creature in its natural environment. He believed that other writers should do the same in their local areas, which would give linked networks of extensive information for humanity over time. | This illustration was included in his ‘Natural History of Selborne’ 1789, where a group of well-to-do men and a woman – in typical fashionable clothes of the time – admiring the beautiful view over the small village. They were assisted by a sturdy, embellished linen tent for refreshments and protection from the sun on this summer’s day, contrasting with a group of fieldworkers in working dress in the valley. (Courtesy: The Trustees of the British Museum. No: 16113661303).One may also emphasise that to know a little about everything from a global perspective was not something White favoured, even if he commented on exotic stuffed birds and other specimens when coming across various such collections in London, etc. Like in a letter to Daines Barrington on October 8, 1770:

- ‘Men that undertake only one district are much more likely to advance natural knowledge than those that grasp at more than they can possibly be acquainted with: every kingdom, every province, should have its own monographer.’

The famous Carl Linnaeus was not the only naturalist White referred to; another was Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752), who had been a student of Linnaeus and made a journey to Egypt, Palestine, etc. White was particularly interested in Hasselquist’s observations of the migrating patterns of specific birds to Egypt compared to his observations in Selborne (or lack of sightings in Great Britain). Interestingly, he was up-to-date with published literature. In this case, Hasselquist’s journal was published in an English edition in London in 1766, and White mentioned the book just one year later (and still made references in 1779 to Hasselquist in a letter to Barrington). White was also fascinated by curiosity and mystery; he had a very investigative mind and often tried to convey the immediate experience of his observations in his writing. White, as a curate-cum-naturalist, had the same belief as Carl Linnaeus and many other naturalists of the time – God as the creator was always present when drawing conclusions about the Natural World and scientific knowledge. It may also be noted that Linnaeus corresponded with John White (1727-1780) – Gilbert’s brother – in the complex 18th century network of naturalists et al. Just like the naturalist Daniel Solander (1733-1782), shortly after he arrived in London in the summer of 1760, he mentioned Gilbert White in a letter to his former teacher Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala, as illustrated below.

![Page four of a letter from Daniel Solander written on 21 July 1760 from London to Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala. Among many naturalists, the young Swede had met or learned about Gilbert White as a knowledgeable person in natural history, as he briefly mentioned: ’Mr [Gilbert] White, who has a larger bird collection than [George] Edwards…’ (in translation from Swedish). Solander, who had arrived in London about a month prior to this letter, seems to have aimed to inform Linnaeus of all possible naturalists and other persons of interest, due to that more than twenty individuals were mentioned in the letter, besides the ones Solander sent regards to in Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:231128. & The Linnean Society of London. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4-solander-white-linnaeus-1760-664x796.jpg) Page four of a letter from Daniel Solander written on 21 July 1760 from London to Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala. Among many naturalists, the young Swede had met or learned about Gilbert White as a knowledgeable person in natural history, as he briefly mentioned: ’Mr [Gilbert] White, who has a larger bird collection than [George] Edwards…’ (in translation from Swedish). Solander, who had arrived in London about a month prior to this letter, seems to have aimed to inform Linnaeus of all possible naturalists and other persons of interest, due to that more than twenty individuals were mentioned in the letter, besides the ones Solander sent regards to in Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:231128. & The Linnean Society of London. Public Domain).

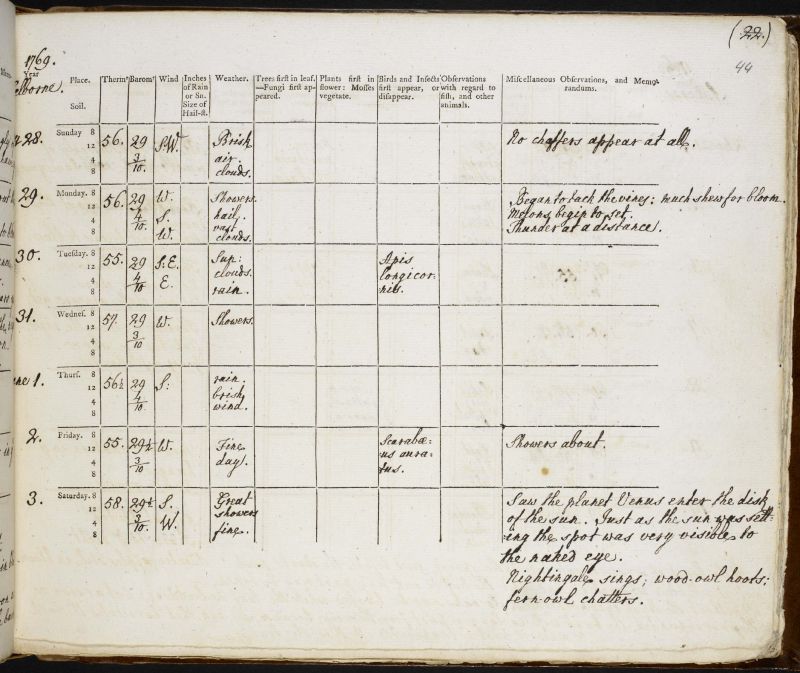

Page four of a letter from Daniel Solander written on 21 July 1760 from London to Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala. Among many naturalists, the young Swede had met or learned about Gilbert White as a knowledgeable person in natural history, as he briefly mentioned: ’Mr [Gilbert] White, who has a larger bird collection than [George] Edwards…’ (in translation from Swedish). Solander, who had arrived in London about a month prior to this letter, seems to have aimed to inform Linnaeus of all possible naturalists and other persons of interest, due to that more than twenty individuals were mentioned in the letter, besides the ones Solander sent regards to in Sweden. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record:231128. & The Linnean Society of London. Public Domain). The full title of Gilbert White’s handwritten naturalist calendar reads: ’The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton. To which are added the naturalist’s calendar, observations on various parts of nature; and poems’. Here exemplified with one page of his words dated 28 May to 3 June in 1769. The information recorded in his Naturalist’s Journal about weather and a multitude of notes about his garden, natural history and agriculture – observations which became helpful for conclusions drawn in his later published letter-form book ‘The Natural History of Selborne’. (Courtesy: British Library. Add. MS 31846).

The full title of Gilbert White’s handwritten naturalist calendar reads: ’The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton. To which are added the naturalist’s calendar, observations on various parts of nature; and poems’. Here exemplified with one page of his words dated 28 May to 3 June in 1769. The information recorded in his Naturalist’s Journal about weather and a multitude of notes about his garden, natural history and agriculture – observations which became helpful for conclusions drawn in his later published letter-form book ‘The Natural History of Selborne’. (Courtesy: British Library. Add. MS 31846).The two series of forty-four and sixty-six letters, written by Gilbert White to be published in The Natural History of Selborne – mainly covered his interests in the field of nature, observations of birds’ migration patterns, the changing seasons, contemporary theories by other naturalists all via his in-depth local studies of living plants and animals in their natural habitats. However, in between various reflections of household economies, named oeconomy in the 18th century, some textile traditions were mentioned. In a letter to Thomas Pennant (undated Letter 5, probably never sent, but dates mentioned in the letter covered the period from 1 May in 1779 to 1 January in 1787). Wool and spinning during winter months by ‘the sober and industrious poor’ was noted:

- ‘Formerly, in the dead months they availed themselves greatly by spinning wool for making of barragons, a genteel corded stuff, much in vogue at that time for summer wear; and chiefly manufactured at Alton, a neighbouring town, by some of the people called Quakers: but from circumstances, this trade is at an end.’ Note: ‘Since the passage above was written, I am happy in being able to say that the spinning employment is a little revived, to the no small comfort of the industrious housewife.’

This was probably a light woollen cloth of corduroy type, also known as a ribbed weave, a fabric which could be woven in various qualities of coarseness. A durable material for trousers, jackets, etc., popular with the country people in 18th century England.

In conclusion, two further letters to Daines Barrington show White’s skilful way of observing useful handicrafts within local households in the countryside. At first, it was noted how beneficial it would have been if more people had learned of the advantages of skilled household crafts in Hampshire. This reflection is also an interesting link, or at least a similar way of notation, compared to recordings of the subject in some of Linnaeus’ Latin publications from the 1730s to 1760s. In particular, White frequently referred to the famous botanist, and as a man of the church, he mastered the Latin language. However, White could not likely read Linnaeus’ journals from the provincial tours in Sweden (in the Swedish language only) carried out in the 1740s, which included substantial sections on the all-important oeconomy. Parts of White’s Letter 26, from 1 November 1775, reads:

- ‘While on the subject of rural oeconomy, it may not be improper to mention a pretty implement of housewifery that we have seen nowhere else, that is, little neat besoms which our foresters make from the stalk of the polytricum commune, or great golden maiden-hair, which they call silk-wood, and find plenty in the bogs. When this moss is well combed and dressed, and divested of its outer skin, it becomes of a beautiful bright-chestnut colour; and, being soft and pliant, is very proper for the dusting of beds, curtains, carpets, hangings, &c. If these besoms were known to the brush makers in town it is probable they might come much in use for the purpose above-mentioned. Note: ‘A besom of this sort is to be seen in Sir Ashton Lever’s Museum’.

- In Letter 37 to Daines Barrington on 8 January 1778, among many matters, White made comparisons of linen and woollens in Wales: ‘The use of linen changes, shirts or shifts, in the room of sordid and filthy woollen, long worn next the skin, is a matter of neatness compositely modern; but must prove a great means of preventing cutaneous ails. At this very time, woollen instead of linen prevails among the poorer Welch, who are subject to foul eruptions.’

Notice: Quoted sections in letters to Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington of this essay have been cited from – Gilbert White’s The Natural History of Selborne (edited by Anne Secord, Oxford 2013).

Sources:

- British Library, London, United Kingdom. Collection online. (Information about an illustrated Gilbert White manuscripts).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (search words: Gilbert White, English naturalist and clergyman).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017. (Research of Carl Linnaeus’ publications on the household economy and textiles).

- Mabey, Richard, Gilbert White: A biography of the author of The Natural History of Selborne, London 2006 (quote: p. 65, initially taken from ‘Account Book, 1752-53. TB vol. II p. 323’).

- White, Gilbert, The Natural History of Selborne, edited by Anne Secord, Oxford 2013.

- Uppsala University Library, Sweden (Alvin Online: Letters from Daniel Solander and John White to Carl Linnaeus, 1760s-1770s).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE