ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

GLOBAL TRADE WITH TEXTILE DYES

– Brazil-wood and other Dye Woods used in 18th and 19th Century Sweden

Brazil-wood and other South American woods were useful in textile dyeing and became known and desired in Europe already in the 16th century via the Portuguese and Spanish Colonial Empires. This timber trade continued to be used by diverse societies over several centuries. Sweden was one of many importers of such merchandise in the 18th- and 19th centuries, primarily for the demands of the country’s brazil-wood mills and dye works. Other long-distance sea-traded woods suitable as dyes originated in Asia and are named sappan wood. This essay will look closer at some of these dyes – traced via contemporary travel journals, import lists, instructive dye books, artwork, rediscovered links to a dye manufacturer on a 1760s map, as well as a preserved tool once used for the preparation of such dyestuff – my own practical dyeing experiments with brazil-wood in the 1980s aim to give further insight into this practice.

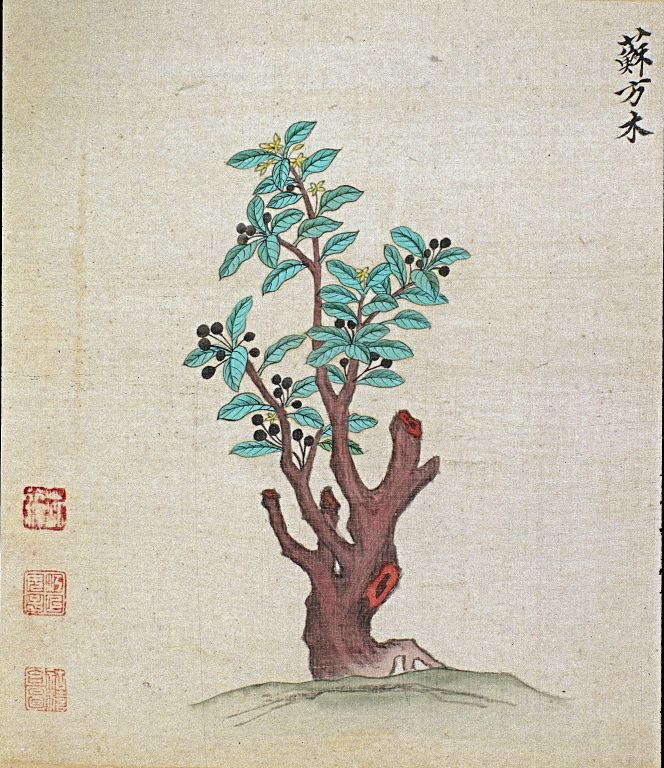

Caesalpina belongs to the plant family Luguminosae, genus Casalpiniodeae, a group of trees and bushes growing in tropical areas. For several Caesalpina species, the wood has been used as a dyestuff for centuries. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images: Artist, Zhou Hu and Zhou Xi, Japan).

Caesalpina belongs to the plant family Luguminosae, genus Casalpiniodeae, a group of trees and bushes growing in tropical areas. For several Caesalpina species, the wood has been used as a dyestuff for centuries. (Courtesy: Wellcome Images: Artist, Zhou Hu and Zhou Xi, Japan).The most sought-after were brazil-wood and pernambuco from South America and sappan from southeast Asia (a trade that had existed since the Middle Ages between East India and Europe). Here, it is illustrated with a sappan tree on a silk painting dated 1644, originally included in a Japanese herbal. This tree was native to tropical South Asia, meaning that the dye wood had to be imported to Japan; among other sources, this is evident via the Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg’s (1743-1828) travel journal in early September 1775. He wrote: ‘The articles which the Dutch company sent this year were a large quantity of soft sugars, elephants’ teeth, sappan-wood for dyeing, also a large quantity of tin and lead, a small quantity of bar-iron, fine chintzes of various sorts, Dutch cloths of different colours and degrees of fineness, shalloons, silks, cloves, tortoise-shell, China root, and Costus Arabicus.’ The Dutch East India Company (VOC) had sailed from Batavia on Java with these commodities, with various origins. Still, it is highly likely that the sappan wood that the Japanese desired for red dyes had been harvested in Java. Similarly, this particular dye wood also found its way to dyers in Sweden via the Swedish East India Company or via reexport from some of the other European companies – in complex trading networks.

![During one of his provincial Swedish tours, the journey to Västergötland in 1746, the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) noted in his travel journal that the town of Borås had three dye works, one of which was ‘Langlet’s dye-works’ where he and his travelling companions had the opportunity to watch many stages of the dyeing process on 5 July. This map of the manufacturing town Borås, drawn about twenty years later, gives an enlightening view of the place. From a dyeing perspective, the house and surrounding fields with the letter [l] were named ' Dye plantation’ in the text. Even if brazil-wood was first mentioned two days later in the neighbouring town of Alingsås, such dye wood was probably used in the dye works in this town. | Map by the cartographer J. Forsell in 1767, watercolour pencil drawing. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 2000098. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2a-boras-1767-800x623.jpg) During one of his provincial Swedish tours, the journey to Västergötland in 1746, the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) noted in his travel journal that the town of Borås had three dye works, one of which was ‘Langlet’s dye-works’ where he and his travelling companions had the opportunity to watch many stages of the dyeing process on 5 July. This map of the manufacturing town Borås, drawn about twenty years later, gives an enlightening view of the place. From a dyeing perspective, the house and surrounding fields with the letter [l] were named ' Dye plantation’ in the text. Even if brazil-wood was first mentioned two days later in the neighbouring town of Alingsås, such dye wood was probably used in the dye works in this town. | Map by the cartographer J. Forsell in 1767, watercolour pencil drawing. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 2000098. Public Domain).

During one of his provincial Swedish tours, the journey to Västergötland in 1746, the naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) noted in his travel journal that the town of Borås had three dye works, one of which was ‘Langlet’s dye-works’ where he and his travelling companions had the opportunity to watch many stages of the dyeing process on 5 July. This map of the manufacturing town Borås, drawn about twenty years later, gives an enlightening view of the place. From a dyeing perspective, the house and surrounding fields with the letter [l] were named ' Dye plantation’ in the text. Even if brazil-wood was first mentioned two days later in the neighbouring town of Alingsås, such dye wood was probably used in the dye works in this town. | Map by the cartographer J. Forsell in 1767, watercolour pencil drawing. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Sweden. Alvin-record: 2000098. Public Domain).Brazil-wood (Paubrasilia echinata or Caesalpinia echinata) was primarily named bresilja in Swedish, but also blåspån (blue chip), brown brazil-wood, brunträ (brown wood) or brunspån (brown chip), which produce black, dark blue to dark violet colours but are relatively poor at tolerating sunlight. According to Carl Linnaeus’ observations, in Jonas Alström’s (1685-1761) storehouse in Alingsås, there were also imported dyestuffs which produced yellow nuances, the foremost of which being ‘gelbholtz’ (yellow wood), also called ‘gulspån’ (yellow chips) or yellow brazil-wood. Such an exotic wood was shipped via the Spanish trade from South America, where the very best quality was thought to have its origin in Cuba. The dyes were delivered in the form of splintered chips and then ground to fine gravel or powder after arrival.

Otherwise, indigo was the most sought-after and admired dye for the highest quality blue colours, but there was, moreover, a more straightforward way of producing a blue colour without the complicated vat-dyeing method, and that was by using imported dye-woods, which only needed to be steeped in a mordant bath with alum. Linnaeus noticed that substance, along with woad and indigo, in the store of Alström’s Manufacture on 7 July in 1746, and likewise bresiletta, which were small pieces of brazil-wood/campeachy wood, which had already been ground into a damp and dripping extract from the same. Using brazil-wood was nonetheless regarded as cheating by some professional dyers, as it could be confusingly similar to indigo or woad. However, the result soon appeared in the form of relatively poor light resistance, and it was particularly hazardous to use brazil-dyed wool together with other lighter colours, as the dyestuff quickly shed. Even so, it was a popular dye.

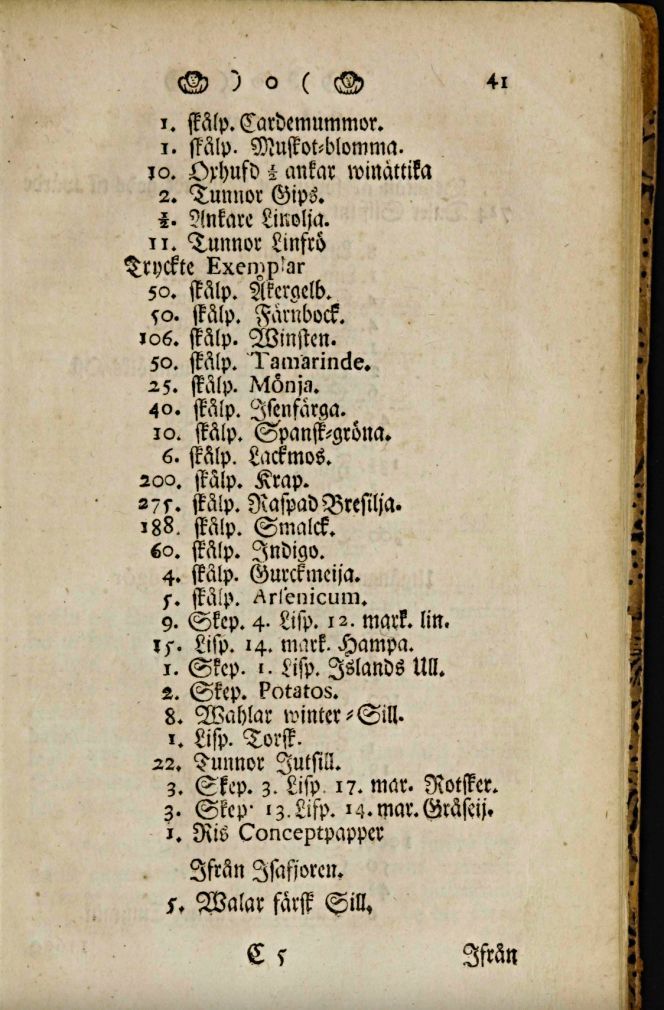

Another traveller during the 1740s was the baron and architect Carl Hårleman (1700-1753), who journeyed from Stockholm to the provinces of southern Sweden in 1749. Among various observations, he made detailed recordings of imports; interestingly, in the centre of this depicted page in the printed journal, he stated, ‘275 pounds of splintered brazil-wood. This dye wood, together with a multitude of exotic long-distance trade (including indigo and madder) together with various European commodities, was part of a ‘List of imported goods at Helsingborg Sea Customs for the year 1748’, which all had been brought in with ships via the harbour town of Helsingør in Denmark. (From: Hårleman… 1749. p. 41. see sources).

Another traveller during the 1740s was the baron and architect Carl Hårleman (1700-1753), who journeyed from Stockholm to the provinces of southern Sweden in 1749. Among various observations, he made detailed recordings of imports; interestingly, in the centre of this depicted page in the printed journal, he stated, ‘275 pounds of splintered brazil-wood. This dye wood, together with a multitude of exotic long-distance trade (including indigo and madder) together with various European commodities, was part of a ‘List of imported goods at Helsingborg Sea Customs for the year 1748’, which all had been brought in with ships via the harbour town of Helsingør in Denmark. (From: Hårleman… 1749. p. 41. see sources).That Carl Linnaeus and his contemporaries were fervent advocates of the excellent qualities of domestically grown plants for dyeing did not exclude the existence of a wide range of imported alternatives. The earlier mentioned manufacturer, Jonas Alström, is the most evident proof of that in Linnaeus’ notes from his Västergötland journey. The storehouses of the manufacture are described as being filled with dyes and dye-grass, a considerable part of which was imported, such as ‘brazil-wood, sappan, Pernambuco, yellow-wood, campeachy wood, wood from Versecz, Japanese wood, weld (French and Swedish), orchil, litmus, woad (English, French, [Thuringian] from Erfurt, Swedish; the two latter equally good and the best), indigo, common madder, sumach, pomegranate peel, laurel berries, oak-apple, cochineal, acorns from a certain species of oak and Spanish pepper’ (7 July 1746). As mentioned initially, the East India Companies formed an essential link in transporting exotic dyes, not only the Swedish company but also the other European companies which carried out trade both directly with the East Indies and together via the Spanish Empire, which had the monopoly of the exchange of goods in dyestuffs from its colonies in South America. The merchants and their partners at different levels made good business deals, but the mystery-making and secrecy surrounding it all were of striking dimensions. Moreover, the account books of the Swedish East India Company were burnt after each audit, making it impossible for any further detailed research to be done into what exotic dyes, for instance, were brought back by those ships.

Examples of colours achieved through experimental blue dyeing of woollen yarn are indigo, brazil-wood and cochineal. Those three imported dyestuffs are to be found described in Carl Linnaeus’ journal Västergötland Journey at Jonas Alström’s manufacture. From the left: 1. Indigo on non-mordanted dark grey yarn. 2. Indigo on non-mordanted white yarn. 3. White yarn mordanted with alum and tartar, dyed with cochineal and indigo afterwards. 4. White yarn mordanted with alum, dyed with cochineal and indigo after that. 5. The darkest blue with brazil-wood on light grey yarn mordanted with alum. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Examples of colours achieved through experimental blue dyeing of woollen yarn are indigo, brazil-wood and cochineal. Those three imported dyestuffs are to be found described in Carl Linnaeus’ journal Västergötland Journey at Jonas Alström’s manufacture. From the left: 1. Indigo on non-mordanted dark grey yarn. 2. Indigo on non-mordanted white yarn. 3. White yarn mordanted with alum and tartar, dyed with cochineal and indigo afterwards. 4. White yarn mordanted with alum, dyed with cochineal and indigo after that. 5. The darkest blue with brazil-wood on light grey yarn mordanted with alum. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. The dyeing experiments with brazil-wood turned out well, producing the deep dark blue (no. 5 illustrated above), according to the following recipe:

- Brazil-wood in the form of small wood chips was put to soak, brought to a boil, and then left to cool. The yarn, pre-mordanted with alum, was used in proportions of 100g yarn to 60g brazil-wood. The yarn was added to the dye bath at 35°C, which was then increased to 90°C for two hours. The dye bath cooled, and the yarn was removed, very thoroughly washed and hung to dry.

The dry yarn bled somewhat initially, but that soon decreased. The colour is still as deep blue after over 40 years, but it has not been exposed to much light or washed.

Several 18th century Swedish dye books and household dictionaries included the subject ‘Bresilja’ [Brazil-wood]; one such example was Lorens Wolter Rothof’s publication over almost 800 pages, printed in 1762. The description of brown and blue brazil-wood stretched over three pages – including instructions to dye black, blue and purple on wool, linen and cotton goods and produce red writing ink.

![Wooden club, for crushing the brazil-wood chips. Initially, the tool – weight 4,8 kg, height 18 cm and diameter 16 cm – was used in the brazil-wood mill of W. Schmidt & Co:s färgstoffmagasin [dyestuff magazine] in Karlshamn, Sweden. This manufacture started in 1810 and continued to circa the year 1900. | The museum acquired this tool and a few other objects linked to the same business in 1924. (Courtesy: Tekniska Museet, Stockholm. TEKS0030021).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5a-digitaltmuseum-664x552.jpg) Wooden club, for crushing the brazil-wood chips. Initially, the tool – weight 4,8 kg, height 18 cm and diameter 16 cm – was used in the brazil-wood mill of W. Schmidt & Co:s färgstoffmagasin [dyestuff magazine] in Karlshamn, Sweden. This manufacture started in 1810 and continued to circa the year 1900. | The museum acquired this tool and a few other objects linked to the same business in 1924. (Courtesy: Tekniska Museet, Stockholm. TEKS0030021).

Wooden club, for crushing the brazil-wood chips. Initially, the tool – weight 4,8 kg, height 18 cm and diameter 16 cm – was used in the brazil-wood mill of W. Schmidt & Co:s färgstoffmagasin [dyestuff magazine] in Karlshamn, Sweden. This manufacture started in 1810 and continued to circa the year 1900. | The museum acquired this tool and a few other objects linked to the same business in 1924. (Courtesy: Tekniska Museet, Stockholm. TEKS0030021).Enlightening information about the general use, unhealthy working conditions and processing of brazil-wood by Swedish professional mill owners and dyers during the 19th century – is particularly evident via Carl Sahlin’s book about his family’s dye works during the 1870s in Vollsjö village, Skåne province. At this time, natural dyes were still commercially used, particularly for wool, even if synthetic dyes dominated. Brazil-wood was by now either imported in finely splintered wood chips or in wooden blocks and splinted into chips in the Swedish factories. The main reason for this continuous use of various South American hardwoods for dyeing blue, brown and black colours to a reasonable cost was that the basic chemical structure of synthetic indigo was worked out by the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer in 1865. Still, difficulties arose when synthesising the “new indigo”; therefore, the substance was first fully developed around 1880, meaning pure indigo in the 1870s was much more expensive than brazil-wood.

Due to the informative nature of Sahlin’s brazil-wood observations, the text will be presented in a complete English translation from the Swedish language:

- ‘Brazil-wood, blue or brown. 5 öre per pound. This for us since long ago, very much known and used dye-wood was imported in blocks via Hamburg from South America and ground at Swedish factories. Such establishments existed in several places in the early 1870s. The largest was the Marieberg brazil-wood mill in Mölndal, close to Göteborg, owned by the wholesale dealer Anders Leffler. Another such mill in the Göteborg area was located at Lerjeholm and belonged to the priest A.W. Ekman. Strömma brazil-wood mill was located close to Karlshamn and had its founder A. Hellerström as its founder. It later came into W. Schmidt & Co’s [compare the image above] ownership and manufacturing on a large scale, particularly since steam power was introduced. To this place, the dye wood blocks were imported directly from Yucatan [in Mexico] in full shiploads. Mr. L.W. Herlitz, who had learned the craft at Strömma brazil-wood mill, founded such a mill close to Stockholm. Also, close to Örebro, such a factory was located, which was operated by manufacturer D.J. Elgérus based on tenancy. The production was in this manner: The wood blocks were splinted in the brazil-wood machine after the product was fed between the stones in an ordinary mill. Depending on the thoroughness of the grinding, the result was splint ground or gravel ground brazil-wood. The dust was terrible in the mill, so the workers became strongly coloured both externally and internally. Finally, the heaps of brazil-wood were sprayed with water until a particular desired colour and dampness were obtained. This was named fermenting. Packing was mostly done in barrels of 200 pounds but also bales of 150 pounds weight. Depending on the country of origin of the wood, the product was called Campéche, San-Domingo or Jamaica brazil-wood. The last mentioned was of poorer qualities, so it was never sold to the dye works.’

- ‘Already before the year 1700, there was a brazil-wood mill in Stockholm, founded by Niklas Pauli. In the Royal Library are also kept price lists from another such factory, which belonged to E.A. Bolinder, born 1771- died 1818, named the Dyestuff Manufacturer Mölna.’

It must be noted that today, brazil-wood Paubrasilia echinata is sadly listed as an endangered species in South America due to excessive harvesting for dyeing and other uses over the centuries.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka (Experiments in textile dyeing on woollen yarn; with brazil-wood).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 352-357, 370, 373, 428).

- Hårleman, Carl, Dag-Bok Öfwer en ifrån Stockholm igenom åtskillige Rikets Landskaper gjord Resa år 1749, Stockholm 1749 (p. 41).

- Kjellberg, Sven, T., Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974 (Information about the Swedish East India Company).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Nordisk Familjebok, Stockholm 1905 (Vol. Four, p. 946. search word: Caesalpinia L.).

- Rothof, Lorens Wolter, HushållsMagasin, Första Delen om Hushållsämnen Till Deras nytta, bruk och skada…, Skara 1762 (pp. 66-69).

- Sahlin, Carl, Ett skånskt färgeri, Stockholm 1928 (Quote in translation: pp. 166-168).

- Sandberg, Gösta, & Sisefsky, Jan, Växtfärgning, Stockholm 1979.

- Tekniska Museet [National Museum of Science and Technology], Stockholm. (Historical information about the wooden club for brazil-wood, from the catalogue card at DigitaltMuseum).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Wikipedia: search words: Paubrasilia (also known as Pernambuco wood or brazil-wood).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE