ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HANDICRAFT AND TEXTILE EXHIBITIONS

– A Case Study from 1900 to 1914

To spread knowledge of 18th and 19th century textile traditions, including weaving techniques such as tapestries, weft-patterned tabby type “opphämta” double interlocked tapestries and embroideries of various designs – became one of the main aims for many of the Swedish handicraft organisations founded around the year 1900. This also applied to the Malmö organisation in southernmost Sweden. The interest in traditional art-woven fabrics from rural areas and the copying of patterns from century-old textiles had already started during the second half of the previous century. But now, this trend has become more organised, with handicraft shops, exhibitions, weaving schools, lotteries, and an increased collection of 100- to 200-year-old furnishing materials.

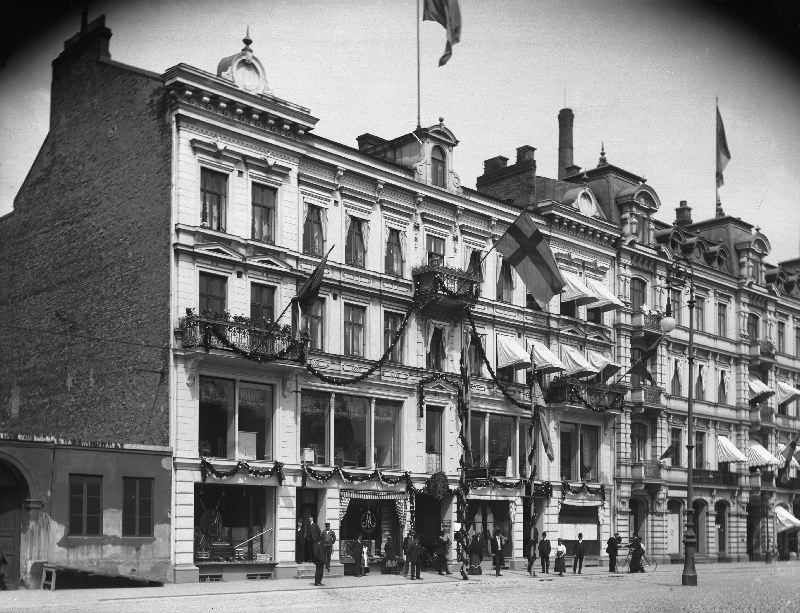

The premises of the handicraft organisation in Malmö 1908 – at Gustav Adolfs Torg 45 – situated close to a busy market place in the Old Town. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EF 000207. Photo: by Viktor Roikjer).

The premises of the handicraft organisation in Malmö 1908 – at Gustav Adolfs Torg 45 – situated close to a busy market place in the Old Town. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EF 000207. Photo: by Viktor Roikjer).The Malmö Handicraft organisation was introduced in 1905, closely linked to the Association of Swedish Handicraft founded in 1899 by Lilli Zickerman (1858-1949). Her ideals, just as many other individuals interested in historical textiles and culture in the late 19th century, was a combination of the “old local handicraft” and the English style as, for instance, William Morris (1834-1896) advocated. Furthermore, in 1899, Zickerman visited England and admired the textiles at Morris & Company in Oxford Street, London. Ellen Key (1849-1926) was another Swedish promoter of the new good taste, which was regarded to give a brighter, more qualitative and harmonious lifestyle – primarily for the bourgeois and inhabitants of similar living standards. The best examples of such interiors were the artist Carl Larsson’s home at Sundborn or a vicarage or well-to-do farmer’s home, where the late 19th century cluttered fashions for home furnishing never had been established.

The interior of the same shop in 1908 gives a glimpse of the display, including textile furnishing – possible to buy ready made or to weave/embroider oneself after motifs and techniques with traditions stretching 100 years or more from the local area – and other handicraft objects. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EF 000228. Photo: by Viktor Roikjer).

The interior of the same shop in 1908 gives a glimpse of the display, including textile furnishing – possible to buy ready made or to weave/embroider oneself after motifs and techniques with traditions stretching 100 years or more from the local area – and other handicraft objects. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EF 000228. Photo: by Viktor Roikjer).The original board for the organisation in Malmö lacked any representation from the farming community or individuals practically involved in weaving etc. Instead, the majority of the members included persons from the nobility living close by together with a professor, a senior master, a wholesale dealer and a member of the Riksdag. However, this group seems to have been representative, as it was the well-to-do who had the opportunity and time to take part in such a primarily unpaid historical and cultural interest. Just as the customers of such handicraft products mainly belonged to the same circles in society – as handmade textiles cost more than fabric-made or if one had the privilege of many hours of leisure time to reproduce large-scale embroideries. But during this period of time, the organisation also had an intense interest in engaging farmers’ daughters or women from working homes in practical paid textile work, whilst these handicraft occupations were regarded to give a decent living.

This particular bedcover woven in “opphämta” with linen warp and linen/woollen weft was one of many textiles purchased by or donated to the handicraft organisation in its earlier years. Such interior textiles produced locally before the year 1900 became an important part of their historical collection, used for various exhibitions and copying of designs for selling newly made reconstructions or yarn to the customers knowledgeable in weaving. Part of bedcover, full size 160x140 cm, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, No: MSSH-0154. Digitalt Museum).

This particular bedcover woven in “opphämta” with linen warp and linen/woollen weft was one of many textiles purchased by or donated to the handicraft organisation in its earlier years. Such interior textiles produced locally before the year 1900 became an important part of their historical collection, used for various exhibitions and copying of designs for selling newly made reconstructions or yarn to the customers knowledgeable in weaving. Part of bedcover, full size 160x140 cm, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, No: MSSH-0154. Digitalt Museum).As shown in the two images above, the shop of the handicraft organisation was from 1908 situated at a suitable central location in Malmö. Besides the selling of textiles, wooden furniture, and other crafted goods in the shop, plenty of other projects were ongoing. From 1907, a lottery took place each year to increase the interest in handicraft wares to a wider group in society and simultaneously to get income from the lottery. A weaving school was another important branch, starting in 1906; the education included local art-weaving from Skåne, knowledge of tools, weave construction and cloth analysis. Woven and embroidered furnishing textiles from the 18th and 19th centuries were purchased and donated to the organisation; the collection increased rapidly in size over a few years. These textiles were used for educational purposes, inspiration for reproductions and the extensive exhibition work, which became more frequent during the 1910s and 1920s.

Some years prior to the foundation of the handicraft organisation – in 1896 – a Nordic Industry and Handicraft Exhibition also took place in Malmö. Exhibitions on these themes had been common and very popular in Europe since the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, and the Malmö exhibition was no exception. Traditional local furnishing was richly represented and mixed with news like machine-embroidered tablecloths, the Art & Crafts movement’s designs and the Jugend style. Eighteen years later – in 1914 – the Malmö Handicraft organisation had the possibility to demonstrate their widespread textile work during the Baltic Exhibition.

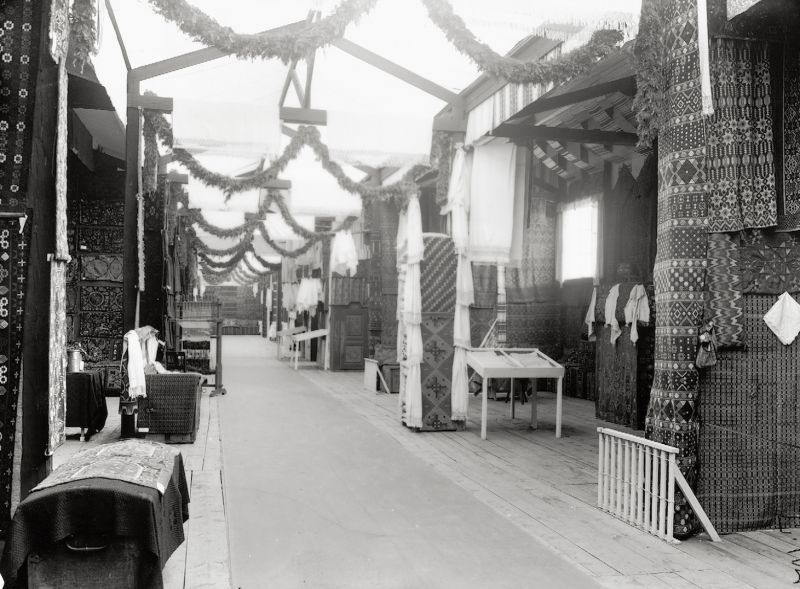

The handicraft organisation of Malmö showed some of their extensive collections at the “Handicraft road” during the Baltic Exhibition in 1914. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EM 1072).

The handicraft organisation of Malmö showed some of their extensive collections at the “Handicraft road” during the Baltic Exhibition in 1914. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EM 1072).This event became the largest exhibition in the history of Malmö, constructed in present-day Pildammsparken (Willowpond Park) with exhibitors from Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Russia. The 1914 Baltic Exhibition was opened on 15 May, but it ended abruptly on 4 October at the outbreak of the war. The event was seen as spectacular at the time, with more than 1.700 exhibitors showing the latest in industry and craft, as well as traditional textile handicrafts, etc. This interest can be glimpsed from photographs taken during the almost six months in 1914, together with about seventy-five articles and catalogues published between 1913 and 1915.

Textiles were richly represented, newly produced and historical fabrics alike. Several Swedish handicraft organisations took part – with a “Handicraft road” as the main attraction as depicted in the photograph above – and the Malmö organisation was, for the apparent local connection, one of the main exhibitors. Furthermore, Stina Rodenstam (1868-1936), who for many years was engaged in weaving traditions in Hudiksvall – in mid-Sweden – wrote an extensive official report in 1915 about handicrafts on display at the Baltic Exhibition. Some of the Malmö organisation’s work was described as follows in translation:

‘In the exhibition of the Malmö Handicraft organisation, consisting of no less than five rooms, we are first introduced to a main room of a farm in Skåne…Both the so-called long benches and main armchair are decorated with beautiful bench covers and chair cushions of rölakan [double interlocked tapestry]…The second room consisted of a modern bedroom of light polished birch furniture, upholstered with blue-striped cotton fabric, which in colour harmonised with the soft, deep blue carpet…The third room showed the impressive richness of patterns in the traditional art woven textiles…The fourth room was named “the lace room”. There was exhibited a substantial collection of exquisite whitework embroidery, laces etc…In the last and fifth room, necessary textiles for the household were on display – including genuine diaper and damask linen fabrics, curtains, tablecloths, costume and dress fabrics and woven ribbons.’

Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen. This is the final essay – of twenty-three – about the textile history of Malmö.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen pp. 23-91, 1999 (pp. 60-66).

- Malmö Museum, Sweden (Online collection, four photographs & information – catalogue cards).

- Rodenstam, Stina, Hemslöjden på Baltiska Utställningen 1914, Officiell berättelse över Baltiska utställningen i Malmö år 1914, sid 581-643, 1915.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE