ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HANDICRAFT AND TEXTILE INDUSTRY

– a Case Study from 1800s to 1840s

Local weaving of broadcloth and ribbons, a rich tradition of woollen embroideries and woven interior textiles, can be studied from a multitude of preserved documents and objects. From a textile point of view, the first half of the 19th century may overall be considered as a period of change for Malmö in southernmost Sweden, due to the gradual introduction of industrialisation. However, urbanisation was still modest as embroidering and art weaving in the farming communities of the surrounding rural districts reached their peak in perfection during the first three to four decades of the century. This culmination of generations of knowledge – is visible in the style and fineness of patterns as well as in skill and economic ability, such as an extended use of imported natural dyes like indigo, cochineal and madder.

A complexly woven double interlocked tapestry cushion dated 1801, from the village of Hyllie close to/today part of Malmö. (Owner: Malmö Museums no. 29.423). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

A complexly woven double interlocked tapestry cushion dated 1801, from the village of Hyllie close to/today part of Malmö. (Owner: Malmö Museums no. 29.423). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.During the winter of 1806-07, Malmö acted as the unofficial capital of Sweden, as King Gustav IV Adolf lived there with his family. It has not been possible to trace any textiles from their stay in the area, but the locally woven cushion (illustrated above) dated five years earlier has some royal connection. This double interlocked tapestry includes the sentence ‘Albertina Sofia princess of Sweden 1778’ [in translation from Swedish] together with unidentifiable combinations of characters. Sofia Albertina was the sister of the late Gustaf III and the aunt of the then-present king; furthermore, as an unmarried relative, she often accompanied the family on their journeys in the early 19th century. The exact circumstances of the unique cushion are unknown – but maybe it was intended as a gift for Sofia Albertina or if the woman on horseback was meant to depict her.

An 1804 map of the county of Skåne in southernmost Sweden, including Malmö situated on the west coast by Öresund. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 007880).

An 1804 map of the county of Skåne in southernmost Sweden, including Malmö situated on the west coast by Öresund. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 007880).As described in an earlier essay in this series, Malmö had a long tradition of broadcloth manufacturing; the most influential factories around the year 1800 were named Hoppet and Concordia. The workforce was predominantly female and very young, with 60% under the age of twenty. However, the prosperous woollen trade at Concordia was abruptly interrupted by a violent fire in 1808, and it had difficulties recovering. Another reason for the increased problems of the woollen trade was the new and more effective spinning machines and mechanical looms, which at this period in time were more effective for cotton than wool. One example of a small woollen manufactory in 1840 was owned by Mr Eneström, which primarily produced broadcloth and blankets. Whilst a few individuals were occupied in a minor ribbon manufactory with its roots in the 1820s when a lady named Anna Lärka had started this particular textile business.

Quite a rich selection of early 19th century woollen embroideries, double interlocked tapestries and other art-woven decorative interior textiles are preserved from the close-by districts of Oxie and Bara. Usually these textiles were produced by well-to-do farmers’ wives/daughters and not in the city itself. This well-preserved seat cushion from Hötofta village in Oxie district was marked and dated “KAD 1831”. A weft ribbed fabric – linen warp and woollen weft – with a voided pile weave border, woollen embroidery and a so-called “Kavelfrans” or napped edgings. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0020235. Digitalt Museum).

Quite a rich selection of early 19th century woollen embroideries, double interlocked tapestries and other art-woven decorative interior textiles are preserved from the close-by districts of Oxie and Bara. Usually these textiles were produced by well-to-do farmers’ wives/daughters and not in the city itself. This well-preserved seat cushion from Hötofta village in Oxie district was marked and dated “KAD 1831”. A weft ribbed fabric – linen warp and woollen weft – with a voided pile weave border, woollen embroidery and a so-called “Kavelfrans” or napped edgings. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0020235. Digitalt Museum).

A few samplers dating from the 1820s and 1830s demonstrating educational needlecraft can be traced to merchant families in Malmö, together with a well-preserved home-woven linen pillowcase once belonged to a Boel Olsdotter – marked “BOD 1832” in cross-stitch. This linen case is, besides its monogram, decorated with filet lace of white linen- and red cotton thread, together with a stem-stitch embroidery. According to information from the Malmö museum (MMT 002477), she lived in the city, and this particular textile was probably also made locally.

Portrait, by Pehr Lindhberg of Benedikta Sofia Flensburg (1788-1825) in 1824. She belonged to one of the merchant families in Malmö and her husband Mathias Flensburg (1779-1851) sold local as well as imported food and other goods in his shop. Her clothing reveals some sort of wealth: including a black velvet dress with lace decorations and a red ornamented shawl. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 002002).

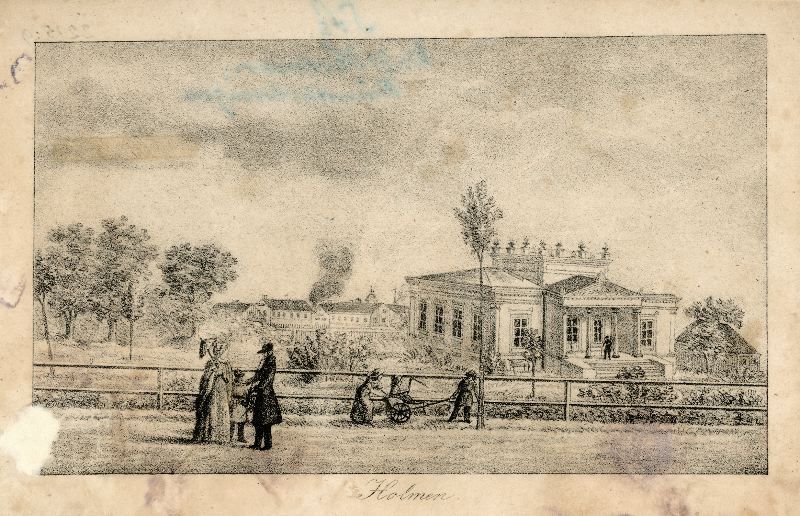

Portrait, by Pehr Lindhberg of Benedikta Sofia Flensburg (1788-1825) in 1824. She belonged to one of the merchant families in Malmö and her husband Mathias Flensburg (1779-1851) sold local as well as imported food and other goods in his shop. Her clothing reveals some sort of wealth: including a black velvet dress with lace decorations and a red ornamented shawl. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 002002). Lithograph by Carl Conrad Dahlberg in 1843 depicted villa “Holmen” with its surrounding park in the outskirts of the growing Malmö – which by then had just over 10 000 inhabitants. A few citizens give example of family life, everyday clothing and fashions from the time. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 02215:009).

Lithograph by Carl Conrad Dahlberg in 1843 depicted villa “Holmen” with its surrounding park in the outskirts of the growing Malmö – which by then had just over 10 000 inhabitants. A few citizens give example of family life, everyday clothing and fashions from the time. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 02215:009).Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen pp. 23-91, 1999 (pp. 46-51).

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943. (Woollen manufactures in Malmö, pp. 647-695).

- Malmö Museum, Sweden (Online collection, images & information on catalogue cards).

- Nordic Museum, Stockholm (DigitaltMuseum, information on catalogue card).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE