ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– "Tvistsöm" Embroidery

Decorating domestic as well as ecclesiastical textiles with tvistsöm or the quite similar cross-stitch technique has at least traditions back to the 13th century in Europe. In southernmost Sweden, this way of embroidering became popular three centuries later and continued to be so up to the 1850s. The motifs used were pomegranates, acanthuses, crosses, stars, stylised flowers, birds, and geometrical borders. The aim of this essay is to share the experience of reproducing two full-size embroideries together with a brief historical introduction of patterns, materials and stitching.

Tvistsöm cushion dated 1771, southwest part of Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0324880, & historical facts from catalogue card. Creative Commons).

Tvistsöm cushion dated 1771, southwest part of Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0324880, & historical facts from catalogue card. Creative Commons).The earliest proof for the technique’s use in Skåne (Scania) can be followed via estate inventories from the 16th century bourgeois in Malmö – described as ‘embroidered on tvist’ – and their embroideries, later on, influenced the wealthy farmers in surrounding districts during the coming centuries. Textile researcher Ernst Fischer also found several pieces of evidence from this type of archive material, concluding that the method of stitching probably got its name, tvistsöm, from the fabric on which it was stitched. Additionally, he points out that the men who recorded these inventories seldom had specialist textile knowledge and, therefore, often had difficulties describing various weaving or embroidery techniques accurately. The tapestry weaving, on the other hand, seemed to have been well known amongst them and, therefore, often used as a comparison, even if the cushion/cover/bedcover was embroidered. Due to this, the written inventories could, for example, list: ‘embroidered with flames’, ‘flame-like’, ‘a tapestry embroidered large table cover with red and white fringes‘ or ‘1 embroidered or tapestry bench cover’ during the 18th century. (Quotes are translated from Swedish; Ingers & Fischer, Tvistsöm… pp. 7-8).

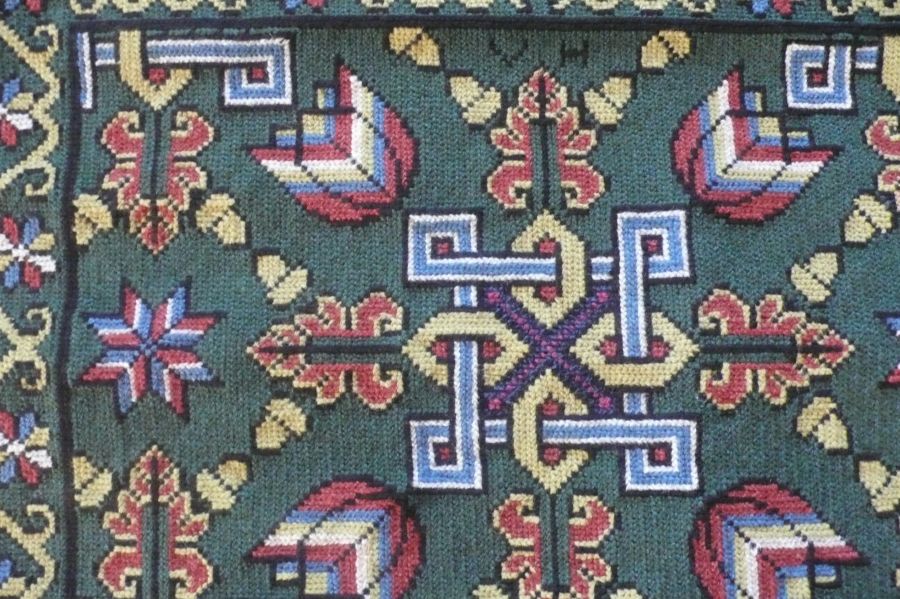

Historical reproduction of a full size tvistsöm cushion (50x66cm, part of illustrated). The original of this motif were embroidered in various sizes for bedcovers and cushions, in Skytts and Oxie districts, Skåne, Sweden. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

Historical reproduction of a full size tvistsöm cushion (50x66cm, part of illustrated). The original of this motif were embroidered in various sizes for bedcovers and cushions, in Skytts and Oxie districts, Skåne, Sweden. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.The attempt above has the same pattern composition as the oldest preserved embroidery of this kind from Skåne, a magnificent bedcover dated 1684 and today kept at the National Museum’s collections in Stockholm. The depicted combination of motifs was embroidered in the southwest part of Skåne – and foremost in the Torna district – with dates stretching up to 1839. Another commonly used pattern in the art of textiles from many cultures was the pomegranates, a group of designs showing ample richness in variation in preserved embroideries from this area, dated at the earliest 1691 and approximately 150 years ahead. Other occurring motifs were primarily: acanthuses, stars, crosses, stylised flowers, birds and geometrical borders.

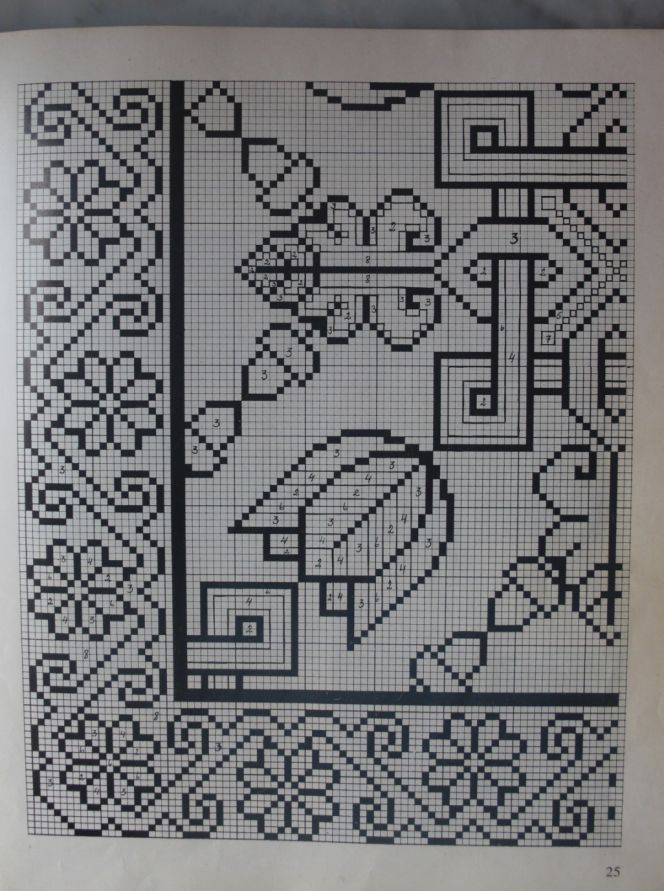

In 1969 the book “Tvistsöm” was published by Gertrud Ingers and Ernst Fischer describing the history of the embroideries as well as depicting reproductions of the old motifs on linen fabric stitched with wool, together with newly composed designs in linen only. Original designs had a renaissance and new compositions became popular during the coming two decades at the Handcraft organisation (Hemslöjden) in Malmö. However the tradition to stitch tvistsöm with inspiration of or embroidering more exact copies from the 18th- & 19th century designs have continued into recent decades, but now foremost by the Hemslöjden in nearby Landskrona supplying designs, yarn and courses. This page from the mentioned book illustrates an example for how the embroidery motifs were explained with additional colour references. Photo: Viveka Hansen.

In 1969 the book “Tvistsöm” was published by Gertrud Ingers and Ernst Fischer describing the history of the embroideries as well as depicting reproductions of the old motifs on linen fabric stitched with wool, together with newly composed designs in linen only. Original designs had a renaissance and new compositions became popular during the coming two decades at the Handcraft organisation (Hemslöjden) in Malmö. However the tradition to stitch tvistsöm with inspiration of or embroidering more exact copies from the 18th- & 19th century designs have continued into recent decades, but now foremost by the Hemslöjden in nearby Landskrona supplying designs, yarn and courses. This page from the mentioned book illustrates an example for how the embroidery motifs were explained with additional colour references. Photo: Viveka Hansen.The wish and interest to reproduce two full-size embroideries of this type – some years ago – had its origin in understanding more of the enormous amount of time the women used to produce interior textiles of this kind, often several years prior to the young woman’s marriage. To copy details of historical textiles to the best possible exactness is something I have carried out in different weaving techniques, embroideries, plaiting and lace making over the years. It has been most fulfilling and enjoyable, but to instead tackle full-scale embroideries gives further respect for yesterday’s women’s deep knowledge, skills and patience. The hours for my embroideries were never counted, which undoubtedly were not prioritised during the 17th-19th centuries when this type of embroidery was an item of status, beauty and skilful handcraft made in wealthy farmer’s homes to be inherited for the next generation and never meant to be sold.

By counting the number of stitches in both directions, one can easily make an estimate for the embroidery reproduction, in the size of 50cm by 140cm – to 172 stitches x 420 stitches = c. 72 240 stitches! Additionally, a farmer’s home in the southwest of Skåne could be the owner of numerous embroideries of this type, not to mention all other textiles made by the female members of the household to demonstrate the family’s wealth, knowledge, handcraft skills and status. This included a substantial storage of all sorts of interior fabrics, which during various festivities decorated the home and embellished the carriage seat with cushions in tvistsöm and other complicated woven/embroidered textiles in a richly coloured combination of patterns. One must also remember that the linen fabric used first had to be woven; the wool spun into yarn and then dyed with natural dyes into preferred shades before the embroiderer could even start her work.

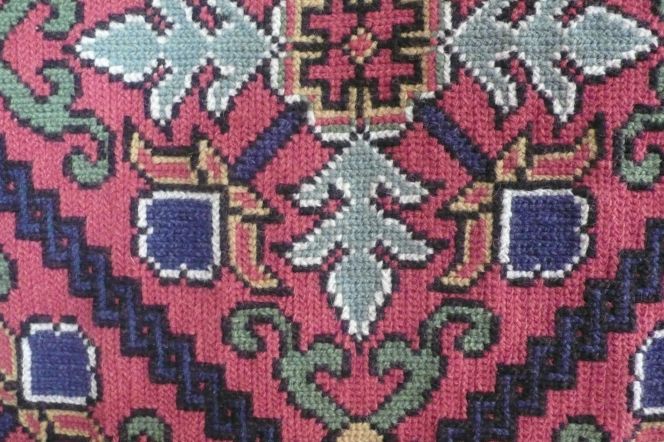

This close-up detail shows a part of the 2nd full size historical reproduction of the technique (50x140cm). The provenience of the original embroidery is Östarp parish, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

This close-up detail shows a part of the 2nd full size historical reproduction of the technique (50x140cm). The provenience of the original embroidery is Östarp parish, Torna district, Skåne, Sweden. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen. Extreme close-up image showing the stitching with woollen yarn and the extended tabby quality of linen for the reproduction; an equivalent linen was made use of for the original embroideries in the 18th- & 19th centuries. The technique in itself is fairly simple – one and a half cross stitch – but the process is rather time consuming when the entire surface is filled with stitches totally covering the linen material. For the reproduction machine woven linen and machine spun yarn was used. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

Extreme close-up image showing the stitching with woollen yarn and the extended tabby quality of linen for the reproduction; an equivalent linen was made use of for the original embroideries in the 18th- & 19th centuries. The technique in itself is fairly simple – one and a half cross stitch – but the process is rather time consuming when the entire surface is filled with stitches totally covering the linen material. For the reproduction machine woven linen and machine spun yarn was used. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.Sources:

- DigitaltMuseum (several examples of “Tvistsöm” embroidery kept in Swedish museums).

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art – Traditional Marriage Weaving, London 1996.

- Hansen, Viveka (Historical Reproduction/embroideries).

- Ingers, Gertrud & Fisher, Ernst, Tvistsöm, Malmö 1969.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE