ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– Dye Plants in 18th Century Sweden and Dyeing Experiments in the 1980s

During a few summers in the early 1980s, I took a great interest in dyeing woollen yarns with local plants in southernmost Sweden. Over the years, these dyed yarns have been used for knitting slipovers, sweaters, mittens etc.; some have been worn out, whilst others still are used within my family. These dyed yellows and browns – all show a good colour strength – a quality which was of particular importance prior to the synthetic dyes (the 1850s) when clothes and textile interior furnishing proportionally were much more expensive than today and due to this, used, reused and altered in various ways during a lifetime. This essay will also give examples of dyeing different yellow and brown shades in the 1730s and 1740s, learned via Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) travel journals printed after his Swedish provincial tours and some of the naturalist’s other botanical publications.

Woollen sweater knitted in 1983 of natural plant-dyed yarn. Despite that, this garment has been frequently used and washed; the colours are more or less unchanged compared to the leftover balls of yarn, which have been kept in a box protected from daylight for 40 years! The strength and durability of these yellow shades have been a positive experience when quite a lot of inspirational work and effort go into dyeing and knitting a garment. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

Woollen sweater knitted in 1983 of natural plant-dyed yarn. Despite that, this garment has been frequently used and washed; the colours are more or less unchanged compared to the leftover balls of yarn, which have been kept in a box protected from daylight for 40 years! The strength and durability of these yellow shades have been a positive experience when quite a lot of inspirational work and effort go into dyeing and knitting a garment. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.Yellow/yellow-beige/yellow-brown nuances have been obtained with the following plants for the natural dyeing experiments:

- cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris)

- wild chamomile (Tripleurospermum perforatum)

- lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum)

- heather (Calluna vulgaris)

- the needles of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris)

- red clover (Trifolium pratense)

- field horsetail (Equisetum arvense)

- tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

- leaves of common alder (Alnus glutinosa)

- rowan (Sorbus aucuparia)

- common hazel (Corylus avellana)

- saw-wort (Serratula tinctoria)

Example of dyeing yellow

The yarn was steeped in a mordant bath with alum, 20g alum/100g yarn and 200g cow parsley flowers/100g yarn.

- The plant parts are boiled for two hours and then left to cool before the flowers are strained away. The pre-mordanted yarn is first soaked before dyeing and is added to the dye bath at 35-40°C. The temperature was increased to 90°C, and the dyeing continued for two hours. The yarn is left to cool in the dye bath, later be thoroughly washed and hung to dry. A solid yellow colour was achieved.

A selection of yellowish shades, possible to dye with plants in southernmost Sweden, indicate the multitude of possibilities which the dyers of pre-synthetic methods undoubtedly had for dyeing wool of such colours with domestic plants. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

A selection of yellowish shades, possible to dye with plants in southernmost Sweden, indicate the multitude of possibilities which the dyers of pre-synthetic methods undoubtedly had for dyeing wool of such colours with domestic plants. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.Likewise, Carl Linnaeus’ observations of dyeing yellow were numerous due to that this colour was the least complicated to produce with plants in the 18th Century. A circumstance which is reflected both in his travel journals and other writings as well as in contemporary printed recipe collections on the dyeing yellows. Besides dyer’s weed, saw-wort, leaves of silver birch and the bark of the apple tree being mentioned in many contexts as the most reliable, domestic dyeing was often based on what was available locally. When there was a good supply of lichen, that is what was used; where the birch woods were dense, its leaves became the natural choice; or if the meadows outside the house were covered in cow parsley, that plant would be used to dye the yarn yellow. Via the provincial tours, methods of dyeing yellow can be traced from Skåne to Lapland, and also with the aid of his publications Flora Oeconomica and Flora Svecica – Svensk Flora, which include several suggestions for that colour.

Dyer’s weed and saw-wort for the dyeing of yellow may have preoccupied Linnaeus in Skåne in 1749, but other common alternatives were also noted on 3rd July, such as ‘birch leaves, scabious and bark of the apple tree’. Two days earlier at Krageholm, he had even heard that the flowers of cow parsley, boiled together with alum, would produce a beautiful yellow colour. The availability of the plants in various regions was thus a crucial factor from a practical point of view. That aspect was also reflected outside Barsebäck on 7th July, where the leaves of bay willow and bog-myrtle were used for dyeing yellow. On the church wall at Virestad in Småland on 13th May, Lichen Viridi Lutens was discovered and recorded as common in the county and ‘with that, the peasants dyed their woollen yarn yellow’. Thus Linnaeus discovered during his tours more and more plants which could be used for dyeing yellow and which, in addition, produced an acceptable result. From his previously undertaken journey to Öland and Gotland (1741), it is evident that dyeing had to adapt to the local conditions, which meant a tougher and drier climate than the more varied one in Skåne. That particular fact concerning shades of yellow is mainly reflected in the far greater use of mosses and bark than in Skåne. The Gotland domestic dyers picked moss off old wooden fences and rocks, ‘which then, boiled with alum, dyed yellow.’ Various kinds of bark were also mentioned in the context, such as alder buckthorn bark, buckthorn bark and apple bark, which were used either raw or dried. ‘Bark from alder buckthorn, boiled raw with water without salt, will yield a yellow colour; but if dried before, will dye brown (29th June)’. On the mainland in Småland on 27th May, he was told of roof moss which grew mainly on shingle roofs of churches and was much used for dyeing yellow. Such notes are clear examples of the many possibilities for dyeing; the same type of bark could yield entirely different nuances, depending on how and when it was used. Saw-wort flourished on Öland too, and on his visit to the dye-works outside Kalmar on 29th May, Linnaeus noticed that the plant was bought from Öland ‘for ten farthings per lb’ [ca 450g]. These are only some of the observations made by Linnaeus on dyeing yellow.

Natural dyeing of wool with birch leaves, cow parsley or flowers of yellow bedstraw produced hardy yellow colours and was described by Carl Linnaeus on several occasions. Here cow parsley with woollen yarn dyed using its flowers, stalks and leaves. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

Natural dyeing of wool with birch leaves, cow parsley or flowers of yellow bedstraw produced hardy yellow colours and was described by Carl Linnaeus on several occasions. Here cow parsley with woollen yarn dyed using its flowers, stalks and leaves. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation. Saw-wort (Serratula tinctoria) was repeatedly recommended by Linnaeus from several Swedish provinces – as noted above – to be a good dye plant. A sheltered and sunny location in the southern part of the country was the most favourable growing condition for this plant. From his journey to Skåne in 1749, he also noted that saw-wort was growing abundantly in the province and, moreover, it was a significant trading commodity; according to Linnaeus, the plant provided the women with a small income in the summertime, as it was transported raw by the cartload and sold at Malmö. What he nevertheless bemoaned on 4the July this year was that the plant which was sold did not remain with the dyers of Malmö but was ‘shipped out to Denmark and other foreign parts before other domestic dyers had got enough…’ That was contrary to common practice in Sweden at the time; that a dye plant was exported instead of being imported. Today, however, saw-wort is sadly a very rare plant in the Nordic area. (Ängsskära/Serratula tinctoria; in Lund Botanical Garden, Sweden). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, 18th May 2022).

Saw-wort (Serratula tinctoria) was repeatedly recommended by Linnaeus from several Swedish provinces – as noted above – to be a good dye plant. A sheltered and sunny location in the southern part of the country was the most favourable growing condition for this plant. From his journey to Skåne in 1749, he also noted that saw-wort was growing abundantly in the province and, moreover, it was a significant trading commodity; according to Linnaeus, the plant provided the women with a small income in the summertime, as it was transported raw by the cartload and sold at Malmö. What he nevertheless bemoaned on 4the July this year was that the plant which was sold did not remain with the dyers of Malmö but was ‘shipped out to Denmark and other foreign parts before other domestic dyers had got enough…’ That was contrary to common practice in Sweden at the time; that a dye plant was exported instead of being imported. Today, however, saw-wort is sadly a very rare plant in the Nordic area. (Ängsskära/Serratula tinctoria; in Lund Botanical Garden, Sweden). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, 18th May 2022).Getting a genuine brown colour with natural dyes was considerably more complex than achieving a yellow hue before synthetic dyes; various types of moss, lichen and bark were commonly used. Some herbs can also yield brownish colours with varying results, but most frequently tending towards yellow. Linnaeus studied one such plant during his tour of Skåne on 25th June 1749. ‘Bur-marigold was collected when she was ripe and yellow in order therewith to dye yellow-brown’.

For dyeing brown, used on the woollen sweater above, cinder lichen (Aspicilia cinerea), also referred to as Stenmossa (rock lichen) by Linnaeus, was the most important source, as described from his provincial tours in Sweden during the 1740s. What is so special about that lichen is that it yields a strongly brown-red colour to woollen yarn without needing mordanting baths. When I did the experiments with dyeing, his note from Småland in 1741 was followed, that is to say, that the lichen was best boiled in the water, which was then strained off before the yarn was added to prevent the yarn from becoming blotchy. The dyeing continued for three hours at 90°C, and the yarn then became the expected even brown-red or russet colour.

There were no notes on the subject of brown shades from Linnaeus’ tour of Västergötland in 1746. Still, a closer study of the weaving manufacturer Jonas Alström’s store of imported dyes makes it clear that the dyeing of brown could have been done there. In the storehouse was to be found on 7th July ‘sandal-wood, madder, yellow-wood and oak-apple’ which together gave a brown colour, although with time, the colour probably changed to more red, bearing in mind the poor light-resistance of sandal-wood. Sandal-wood was an imported tropical dye-wood, which like yellow-wood, roots of common madder and oak-apple, was chipped or ground to a powder.

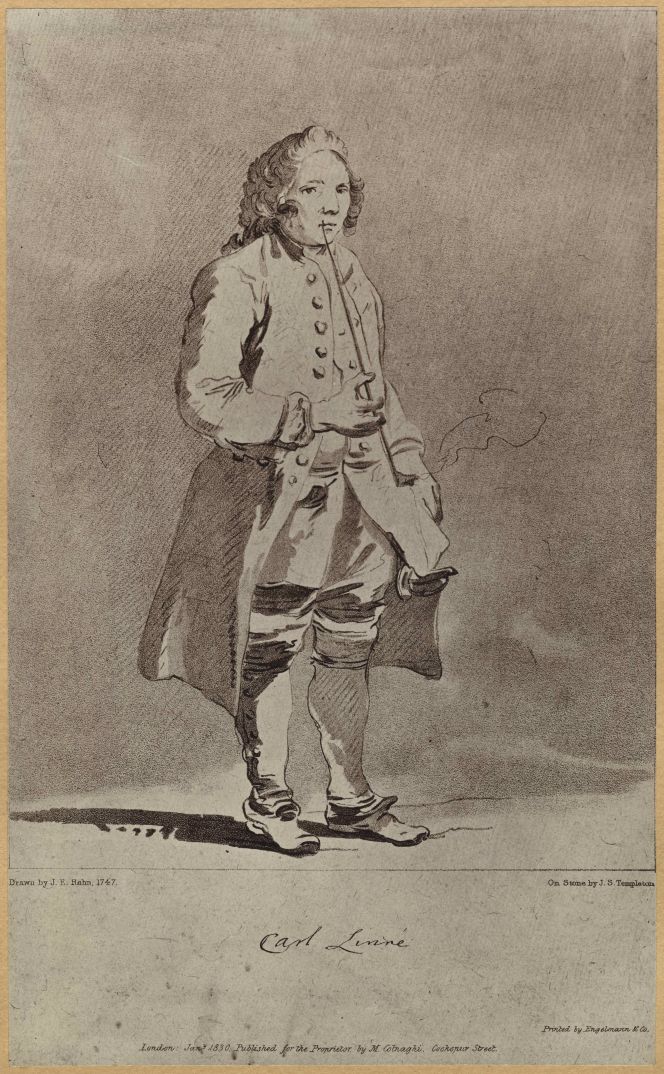

In concluding words about, Carl Linnaeus, who was depicted as a forty-year-old man in 1747 in this portrait – during the same decade when three of his provincial tours in Sweden took place, financed by the parliament to first and foremost find improvements for the mercantile economy of the nation. Observations of natural dyeing with domestically grown plants and to aim for minimisation of import were significant parts of his provincial tours. Initially drawn by the young but well-established artist Jean Eric Rehn (1717-1793), this portrait demonstrates Linnaeus in everyday clothing. He likely used the same or a similar collarless coat, long waistcoat, breeches, long white stockings and practical low-heeled square-toed shoes during his travels.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017. (Read more about Carl Linnaeus’ observations of natural dyeing. pp. 345-87 & Appendix I).

- Hansen, Viveka. (Natural dyeing and knitting of garments: practical experiences by the author of this essay).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa…åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Flora Oeconomica 1737, Uppsala, facsimile 1971.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Svensk Flora – Flora Svecica, Stockholm 1986.

- Lund Botanical Garden, Sweden. | Visit in May 2022.

- Uppsala University Library, No: 17222/Alvin online source (Engraving depicting Carl Linnaeus, c. 1830 after copy by Jean Eric Rehn in 1747).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE