ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– Bobbin Laces from Southernmost Sweden

Lacemaking and whitework embroideries demonstrated an extraordinarily fine quality in the southeastern part of the province Skåne prior to industrialisation around 1850. Laces of various designs and complexity decorated bedlinen, long shirts, and other linen garments often intertwined in domestic economies and associated with preparation for marriage via the young woman’s dowry in the well-to-do farming communities. This essay aims to briefly introduce these particular lacemaking traditions, together with the reproduction of such laces. Even if my attempts to make laces from the province of Skåne in southernmost Sweden – more than forty years ago – were on an elementary level, the practical experience gave me a valuable understanding of historical lacework, which was helpful on several occasions in later archival and museum studies.

This well-preserved detachable collar, once used on a linen bridegroom’s shirt, is an example of the rich traditions in Skåne – to combine laces and whitework embroidery in mirroring designs. The handmade linen bobbin lace used for this collar is 4,5 cm wide, dating circa 1800-1840, an acquisition made already in 1875 via the artist and folklore researcher Nils Månsson Mandelgren to the Nordic Museum. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum…NM.0009990).

This well-preserved detachable collar, once used on a linen bridegroom’s shirt, is an example of the rich traditions in Skåne – to combine laces and whitework embroidery in mirroring designs. The handmade linen bobbin lace used for this collar is 4,5 cm wide, dating circa 1800-1840, an acquisition made already in 1875 via the artist and folklore researcher Nils Månsson Mandelgren to the Nordic Museum. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum…NM.0009990).Observations by the naturalist Carl Linnaeus during his journey to Skåne in 1749 appear to be one of the earliest notes about using laces in festive clothing in farming communities. This was on 18 May this year, at a visit at Sinclairsholm in the northern part of the province, where the men wore a knee-length coat of bluish-grey broadcloth with horsehair buttons from the neck to the breeches. Moreover, the sleeves had cuffs and flaps at the back, and ‘all the button holes are sewn of brown yarn of camel [angora goat] hair’. The linen shirt had a wide collar, richly embroidered and edged with lace. However, long before this time – 16th and 17th centuries – it is known via preserved portraits that wide laces as a part of the dress were in frequent use by wealthy individuals in the province of Skåne. At what exact time lacemaking became popular within the broader strata of society in this part of Sweden (part of Denmark before 1658) is unknown. Even if the shirts of linen evidently were in use in the early 17th century in the province, it is uncertain to what extent such garments had extra decorations like lacework. Another aspect was the itinerant pedlars of the Västergötland area from around 1750, who may have sold lacework from the “lace centre” Vadstena in Sweden. These pedlar had special privileges for rural trading, a trade carried out in a south-north direction from the provinces of Skåne to southern Norrland. Such a trade may also have influenced lacemaking to thrive and develop further in various regions.

The reproduction of 10 lace samples is illustrated and described below in five images, including lace designs, linen threads, technique and tools compared to a 19th century lace of a more complex type.

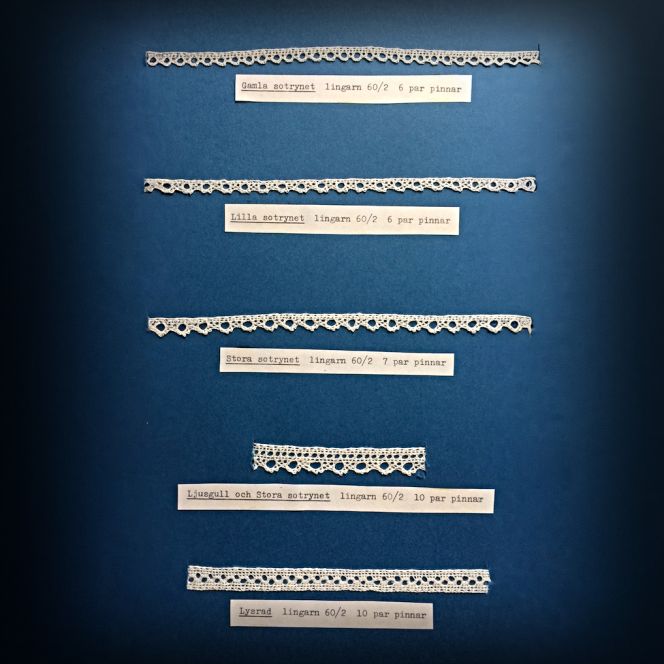

Reproduction of bobbin lace samples 1-5, with their local names underlined, the kind of linen thread used and the number of bobbin pairs used for each lace. All laces are between 0.5 and 1 cm wide. (Private ownership of lace samples, made in 1981-82. Photo: Viveka Hansen).

Reproduction of bobbin lace samples 1-5, with their local names underlined, the kind of linen thread used and the number of bobbin pairs used for each lace. All laces are between 0.5 and 1 cm wide. (Private ownership of lace samples, made in 1981-82. Photo: Viveka Hansen). Five further bobbin lace samples (6-10), with their local names underlined, the type of linen thread used and the number of bobbin pairs used for each lace. All these laces are also 0.5 to 1 cm wide. (Private ownership of lace samples, made in 1981-82. Photo: Viveka Hansen).

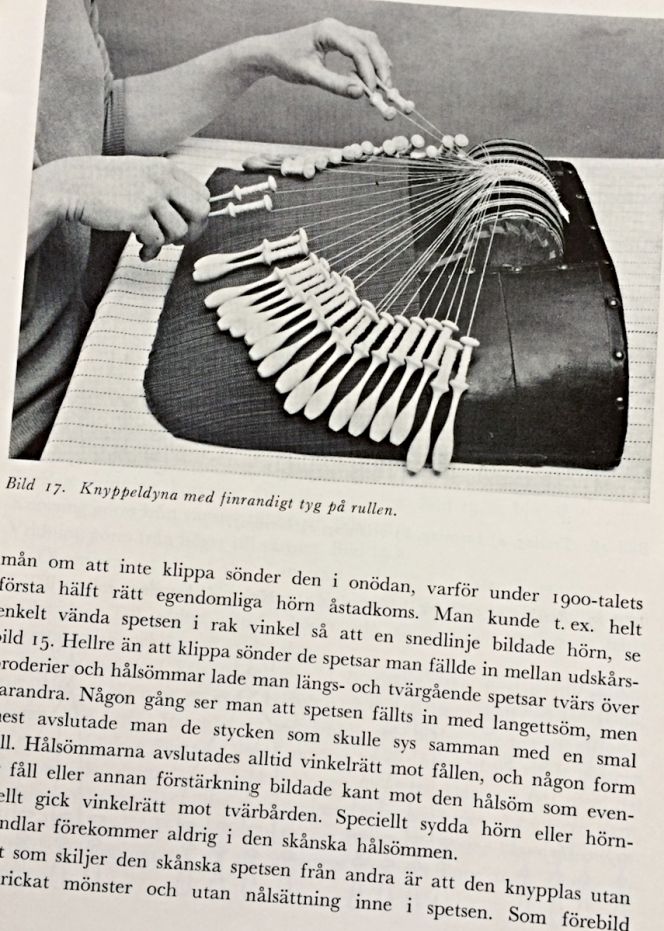

Five further bobbin lace samples (6-10), with their local names underlined, the type of linen thread used and the number of bobbin pairs used for each lace. All these laces are also 0.5 to 1 cm wide. (Private ownership of lace samples, made in 1981-82. Photo: Viveka Hansen). A typical roller pillow for bobbin lacemaking in Skåne, almost identical to the one used for my attempts at lacemaking. Notice the striped fabric on this roller, which assisted the lacemaker with pins placed at the lace edges to keep the exact and desired width of the lace. However, a different form of lace was made in other parts of Sweden where a paper design was used/fastened on the roller, requiring the lacemaker to put pins after prearranged pin holes when the lace advances.(From the book: Ingers, Gertrud… 1966. p. 37).

A typical roller pillow for bobbin lacemaking in Skåne, almost identical to the one used for my attempts at lacemaking. Notice the striped fabric on this roller, which assisted the lacemaker with pins placed at the lace edges to keep the exact and desired width of the lace. However, a different form of lace was made in other parts of Sweden where a paper design was used/fastened on the roller, requiring the lacemaker to put pins after prearranged pin holes when the lace advances.(From the book: Ingers, Gertrud… 1966. p. 37). Bobbins of wood and linen threads for the reproductions, the used thread had the fineness named 60/2, but coarser as well as finer qualities exist. (Private ownership. Photo: Viveka Hansen).

Bobbins of wood and linen threads for the reproductions, the used thread had the fineness named 60/2, but coarser as well as finer qualities exist. (Private ownership. Photo: Viveka Hansen). This traditional handmade linen bobbin lace from the province of Skåne was made in an unknown year during the 19th century. This is an advanced lace with a width of 6 cm, depicting stars and opposite-standing birds in a tree of life. All these motifs were popular for other contemporary handcrafted home furnishing textiles too from the region, like tapestry weaving, art woven cushions of several techniques, whitework embroidery, etc. 48 pairs of bobbins were used in this complex and beautiful lace. (Private ownership. Photo: Viveka Hansen).

This traditional handmade linen bobbin lace from the province of Skåne was made in an unknown year during the 19th century. This is an advanced lace with a width of 6 cm, depicting stars and opposite-standing birds in a tree of life. All these motifs were popular for other contemporary handcrafted home furnishing textiles too from the region, like tapestry weaving, art woven cushions of several techniques, whitework embroidery, etc. 48 pairs of bobbins were used in this complex and beautiful lace. (Private ownership. Photo: Viveka Hansen).To conclude, many museum collections in Sweden have quite an extensive number of preserved linen garments and bedlinen, with decorative bobbin laces of the “Skåne type” dating from 1800 to circa the 1850s. However, this matter does not indicate that such lacework stopped being used during the second half of the 18th century, but handmade examples from this period are primarily rarer due to the increased popularity of machine-made lace. Depending on the planned use of these bobbin laces, qualities seem to vary from relatively coarse on everyday linen shirts and bed linen to very fine, exceptionally so on detachable bridegroom shirts. Locally, the handmade bobbin lacemaking also lived on for much longer due to a family named Ehrensvärd at Tosterup Manor House in the southeast corner of Skåne. This traditional handicraft was researched by the late textile historian Gertrud Ingers in the 1960s, who described some enlightening details of everyday life and hands-on skills. Here is quoted in translation:

- ‘The Ehrensvärd family understood that lacemaking represented an art form which just could not disappear, so from the manor house of Tosterup, they supported all work of whitework and lace, which had been made by local women over time and from the 1830s and 1840s, had been told that the countess of Tosterup each Monday had a reception for the women living in the villages close by. The material was handed out for spinning and weaving, the readymade goods were received, thread for bobbin lacemaking was handed out, readymade laces were checked and discussed, and everyone got their payments. Every skilled woman in lacework – and they were numerous – specialised in their own patterning, whilst they had been introduced to the craft as young girls with the most narrow laces, and some of them became very skilled lacemakers over time. The thread was always the best available. All laces, delivered from the cottages, more or less were grey of the peat smoke, but this was seen as a piece of evidence that it was genuine local lacework.’ (Ingers… pp. 23-24).

The women took great pride in their work, and such delicate laces were sold via the Ehrensvärd family over generations to friends and acquaintances in Stockholm for almost 100 years or up to the 1930s. Prior to this – during the first decade of the 20th century – the handicraft organisation in Malmö had followed up this work with exhibitions, selling of readymade laces, inspiring others to learn lacemaking and document the traditions in publications alike. This was the very same handicraft organisation where I purchased linen threads, accessed tools and learned the basics of the local bobbin lace technique of the “Skåne type” in a series of workshops in the early 1980s.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka (Historical reproductions of ten bobbin lace samples, made in 1981-82).

- Ingers, Gertrud, Skånsk knyppling, Malmöhus läns hemslöjdsförening 1966.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Malmöhus läns Hemslöjd, Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhuslän, Malmö 1916 (pp. 127-159).

- Malmöhus Läns Hemslöjdsförening (Handicraft shop: Purchase (in 1981-82) of linen threads and bobbins used for the reproduction. & Borrowing of a lace cushion for such traditional lacemaking from Skåne).

- Malmöhus Läns och Kristianstads Läns Hemslöjdsföreningar, Skånska spetsar: En kort handbok, Malmö & Kristianstad 1947.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969 (Lacemaking: pp. 295-314).

- The Nordic Museum, Sweden (NM.0009990. Information about this collar with lace & embroidery: DigitaltMuseum).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE