ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– 19th Century Whitework Embroidery

The long history of whitework embroidery has always fascinated me – how, by using the same white linen or cotton sewing thread in a natural way, it developed from the actual sewing of garments and household linen to additionally adorn collars, linings, pillow-cases and all sorts of edgings on fabric. These decorations could be everything from simple borders to highly skilled art forms combined with other types of embroidery and lace-making. Just like the earlier essays describing historical reproductions of Swedish textiles, this text focuses on the attempts to copy a few examples of whitework, the materials used and a brief history of the traditions around this particular handcraft. Additionally, it emphasises the techniques’ possibilities, limitations, beauty and the daily life of the embroiderers in southernmost Sweden.

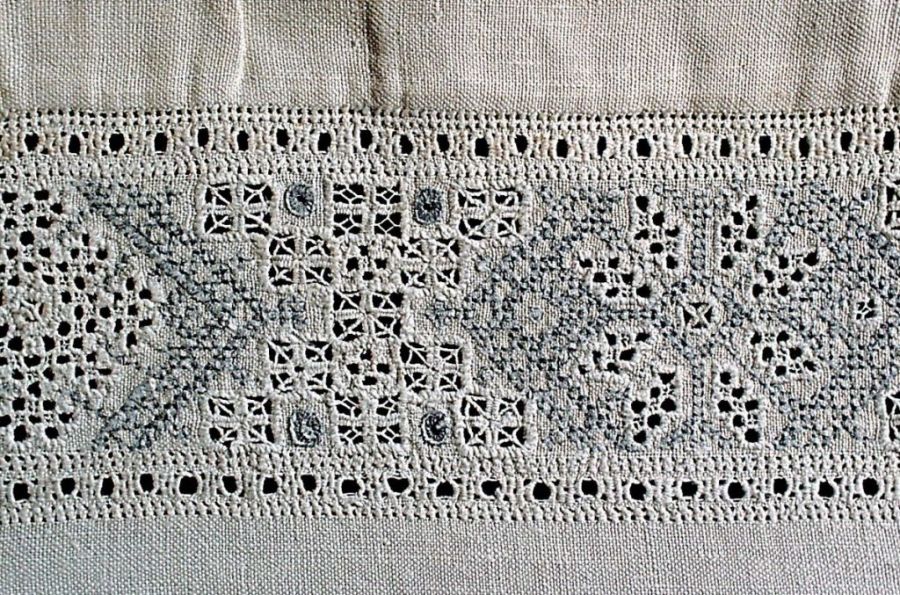

Close up study of a linen pillow-case made in 1838 demonstrating the embroiderer’s skills in various whitework stitching. Borrby parish, Ingelstad district, Skåne, Sweden.(Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, detail of NM.0098458, Creative Commons).

Close up study of a linen pillow-case made in 1838 demonstrating the embroiderer’s skills in various whitework stitching. Borrby parish, Ingelstad district, Skåne, Sweden.(Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, detail of NM.0098458, Creative Commons).Strict geometrical patterning, as on the pillow case above, dominated the skilled embroiderers’ work in southernmost Skåne in the early 19th century, a style originating in the Renaissance tradition of shaping and structuring works of art in symmetrical designs. Even if drawn-thread works have been found in embroideries dating as early as 300-200 BC in Egyptian graves – among other places – the perfection of this style reached its peak in 15th and 16th century Italy. In this geographical area, the advanced embroidery became known as Reticella, using complicated cutwork and drawn-thread work for making scalloped borders, etc.

A second close-up detail of the same pillow-case, additionally showing a monogram in red cross stitch and net embroidery. Made in Borrby parish, Ingelstad district, Skåne, Sweden in 1838. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, detail of NM.0098458, Creative Commons).

A second close-up detail of the same pillow-case, additionally showing a monogram in red cross stitch and net embroidery. Made in Borrby parish, Ingelstad district, Skåne, Sweden in 1838. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, detail of NM.0098458, Creative Commons).In Sweden, just as in many other European countries, it became customary among the wealthy in the 16th and 17th centuries to decorate both garments and bedlinen with various whitework and drawn-thread work techniques, as pointed out by the late textile historian Anna-Maja Nylén in the comprehensive book Swedish Handcraft. This can be studied in many portraits of the time – shirts, collars, and linen headgear, which were often richly decorated with skilfully made whitework as well as needle- or bobbin laces. However, linen was an expensive material and first became more widely spread in society in the early 18th century when flax growth increased. At that time, many areas in Sweden developed their own specialities, and patterns often influenced the early geometrical designs with their roots in the Renaissance. Southernmost Skåne was one such area from where my attempts to reproduce some whitework originated.

-664x499.jpg) The inspiration for some of the stitching was copied from this exquisite whitework sampler copied from a model sewn in the year 1800. This sampler includes 34 variations of whitework ornamentation on a very fine linen – 28 threads/cm, handwoven and sewn with the finest hand spun threads. However the linen for my reproduction was coarser (14 threads/cm) in structure, due to the difficulty in finding such a fine quality linen for embroidery. (Photo: From the publication ‘Ur Skånska syskrin’ p. 10).

The inspiration for some of the stitching was copied from this exquisite whitework sampler copied from a model sewn in the year 1800. This sampler includes 34 variations of whitework ornamentation on a very fine linen – 28 threads/cm, handwoven and sewn with the finest hand spun threads. However the linen for my reproduction was coarser (14 threads/cm) in structure, due to the difficulty in finding such a fine quality linen for embroidery. (Photo: From the publication ‘Ur Skånska syskrin’ p. 10). The attempt to reproduce four whitework embroidery styles on linen (14 threads/cm) with fine 2-ply linen thread (a type of linen thread also used for making hand-made bobbin laces). Top left: a half cross stitch, top right: shadow stitching, bottom left: mock leno effects and bottom right: “basket motif”. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

The attempt to reproduce four whitework embroidery styles on linen (14 threads/cm) with fine 2-ply linen thread (a type of linen thread also used for making hand-made bobbin laces). Top left: a half cross stitch, top right: shadow stitching, bottom left: mock leno effects and bottom right: “basket motif”. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen. Close up study of two of the whitework stitching reproductions – “basket motif” and shadow stitching. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

Close up study of two of the whitework stitching reproductions – “basket motif” and shadow stitching. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.This type of strictly formed patterning was not only in use for whitework embroidery, it inspired all sorts of decorative textiles. It was particularly the case in the wealthy farmer’s areas, used for woollen embroideries, double interlocked tapestries and embellishing many other interior fabrics. In this context, one must consider that even if the origin of the whitework embroideries was rooted in much earlier geometrical designs, it was further developed through various strata of society over many generations to become regional embroidery skills and local special motif combinations. These designs of their own could vary from one district to another in Skåne and even from one parish to the next as late as the mid-19th century. In other words, it is possible to see slight variations in how embroidery, lacework, monograms, fringes, tassels or nets were combined and put together. Traditions, taste, available time for the work, skills, the expectations of an impressive dowry, local trade, geographical isolation, demand and supply of textile raw materials, or possible influence of pattern books – such circumstances could be reasons for developing “unique” local compositions.

The second attempt includes six variation of whitework, embroidered on the same type of linen with 14 threads/cm. Two qualities of strong linen thread (2 ply- and 3-ply) were used, to achieve the effects similar to the early 19th century embroideries made in southern Skåne. From top the stitchings are: 1. ordinary Holbein stitch, 2 & 3 variations of Holbein stitch, 4. diagonal Holbein stitch, 5 & 6. drawn-thread work “H-hålsöm” and “stoppad hålsöm”. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

The second attempt includes six variation of whitework, embroidered on the same type of linen with 14 threads/cm. Two qualities of strong linen thread (2 ply- and 3-ply) were used, to achieve the effects similar to the early 19th century embroideries made in southern Skåne. From top the stitchings are: 1. ordinary Holbein stitch, 2 & 3 variations of Holbein stitch, 4. diagonal Holbein stitch, 5 & 6. drawn-thread work “H-hålsöm” and “stoppad hålsöm”. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen. Close up study of the two drawn-thread work techniques – the so-called “H-hålsöm” and “stoppad hålsöm” in Swedish. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

Close up study of the two drawn-thread work techniques – the so-called “H-hålsöm” and “stoppad hålsöm” in Swedish. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.The cutwork, or “stoppad hålsöm” was the most advanced and time-consuming of the reproductions, even if it was one of the least demanding borders on many of the original complex drawn-thread works! One example can be studied below: on the front of a wedding shirt dating from the 1840s in Herrestads district, which is close to the most southerly coast of Sweden.

![The whitework and drawn-thread work – regularly added with similar motifs in advanced hand-made bobbin laces – adorned the household linen, but to an even greater extent linen shirts and other such garments. This skilled embroidery tradition reached its height in the 1840s in southernmost Skåne, which this shirt is a good example of. The garment was included in the publication ‘Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhuslän’ printed in 1916. The detailed history of the garment is described as follows: ‘Owner: Ingrid Nilsson, Svinarp, Esarp parish, Bara district. Her husband, Jacob Nilsson, from Bromma parish, Herrestads district has inherited the shirt from his parents Nils Olsson and Boel Jacobsdotter, which originally had been his grandfather’s wedding shirt, Jacob Salomonsson in Bromma. It was sewn by his wife Kerstin Mårtensdotter in Bromma, who was known for her skills in making very richly ornamented whitework. A large number of her exquisite work is preserved within the family’ [quote p. 141, translated from Swedish].](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/8-whitework-664x1025.jpg) The whitework and drawn-thread work – regularly added with similar motifs in advanced hand-made bobbin laces – adorned the household linen, but to an even greater extent linen shirts and other such garments. This skilled embroidery tradition reached its height in the 1840s in southernmost Skåne, which this shirt is a good example of. The garment was included in the publication ‘Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhuslän’ printed in 1916. The detailed history of the garment is described as follows: ‘Owner: Ingrid Nilsson, Svinarp, Esarp parish, Bara district. Her husband, Jacob Nilsson, from Bromma parish, Herrestads district has inherited the shirt from his parents Nils Olsson and Boel Jacobsdotter, which originally had been his grandfather’s wedding shirt, Jacob Salomonsson in Bromma. It was sewn by his wife Kerstin Mårtensdotter in Bromma, who was known for her skills in making very richly ornamented whitework. A large number of her exquisite work is preserved within the family’ [quote p. 141, translated from Swedish].

The whitework and drawn-thread work – regularly added with similar motifs in advanced hand-made bobbin laces – adorned the household linen, but to an even greater extent linen shirts and other such garments. This skilled embroidery tradition reached its height in the 1840s in southernmost Skåne, which this shirt is a good example of. The garment was included in the publication ‘Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhuslän’ printed in 1916. The detailed history of the garment is described as follows: ‘Owner: Ingrid Nilsson, Svinarp, Esarp parish, Bara district. Her husband, Jacob Nilsson, from Bromma parish, Herrestads district has inherited the shirt from his parents Nils Olsson and Boel Jacobsdotter, which originally had been his grandfather’s wedding shirt, Jacob Salomonsson in Bromma. It was sewn by his wife Kerstin Mårtensdotter in Bromma, who was known for her skills in making very richly ornamented whitework. A large number of her exquisite work is preserved within the family’ [quote p. 141, translated from Swedish].Sources:

- DigitaltMuseum (Further information about the Pillow-case and several examples of whitework from Skåne in southernmost Sweden).

- Hansen, Viveka (Historical reproductions/embroidery).

- Malmöhus läns Hemslöjdsförening, Gammal Allmogeslöjd från Malmöhuslän, Malmö 1916.

- Malmöhus läns Hemslöjdsförening, Ur skånska syskrin, Malmö 1968.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Swedish Handcraft, Lund 1976.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE