ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– Embroidery in Blackwork or “Svartstick”

Some years ago, out of pure historical interest, I made a number of embroidery reproductions from various provinces in Sweden, originating in the 18th- and 19th centuries. The aim now is to share these samples and compare them with the original embroideries and other primary sources in a new series of essays. This first observation looks closely at the delicate embroidery of the old blackwork technique called “svartstick” in the province of Dalarna. It is one of many fascinating styles of embroidery, once done by very skilled hands to outstanding craftsmanship and artistry.

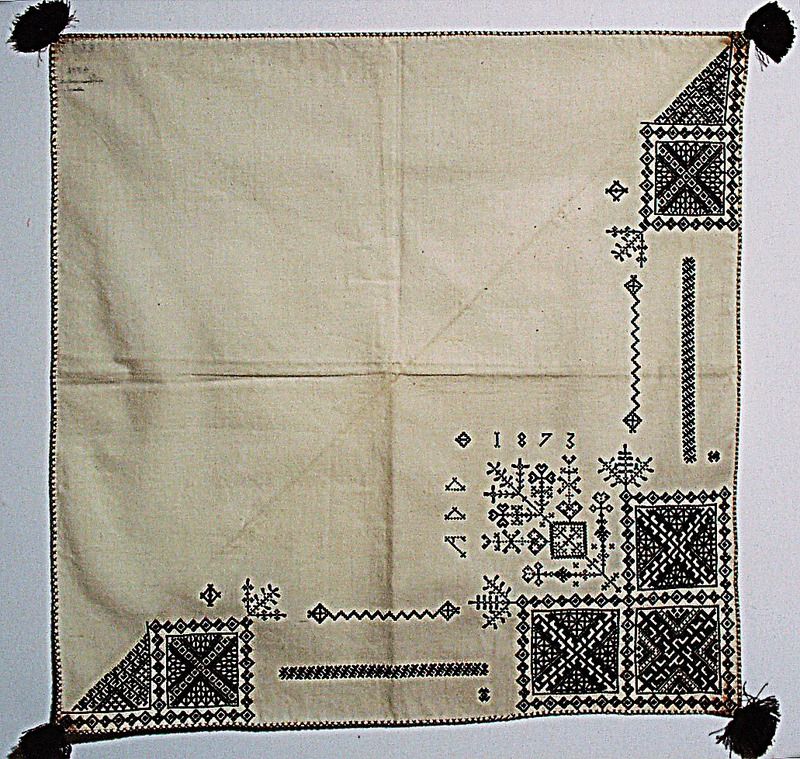

Embroidered neckerchief in blackwork “svartstick” with black silk on cotton, marked ‘ADD 1873’ by Anna Danielsdotter, 24 years old from the village of Tible, Leksand parish, Dalarna, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0004304, Creative Commons).

Embroidered neckerchief in blackwork “svartstick” with black silk on cotton, marked ‘ADD 1873’ by Anna Danielsdotter, 24 years old from the village of Tible, Leksand parish, Dalarna, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, NM.0004304, Creative Commons).The blackwork technique has a widespread history with its roots in Medieval times, but the technique can mainly be studied from exclusive embroidered details in clothing/fashion depicted in works of art from the 16th century. For example, in Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1497-1543), many portraits or, on numerous occasions, depictions of Elizabeth I (1533-1603). However, in Sweden, this type of blackwork also became immensely popular, with the well-to-do during this period, and later on, it also spread to and influenced more groups in society.

During the 19th century, the blackwork in Sweden had developed into a so-called provincial embroidery – foremost in Dalarna – where it became known as “svartstick” [black stitching], where the technique was embroidered with black silk on white cotton fabric. As shown in the photograph above, the style of stitching was used to decorate neckerchiefs belonging to the female festive dress of the parish Leksand. The said garment holds several local names, among others “Svartsticksklädet” and “Tuppaklädet”. The embellishing corner tassels were also important details, coming to their best advantage when used as a triangular folded neckerchief to beautify the women’s best clothing. Judging by the fact that several hundred neckerchiefs – with an almost identical layout of individually chosen embroidery patterns – are kept at Swedish museums today, they must have been frequently used in this geographically restricted area of one single parish.

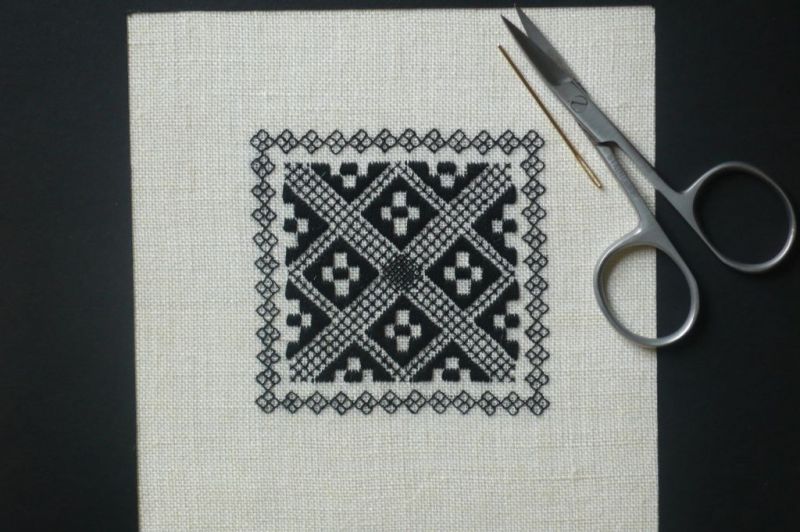

Historical reproduction of “svartstick” on unbleached linen (15 threads/cm) with black silk. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.

Historical reproduction of “svartstick” on unbleached linen (15 threads/cm) with black silk. Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen.The attempt to reproduce the embroidery type was made with black silk in cross-, back-, square- and satin stitches. Such original 19th century embroideries were usually sewn on cotton, which was regarded as superior and more fashionable than linen. However, it was not possible to find a similar type of cotton material, so it was decided to use fine linen as a replacement. The combination of stitches is not complex in itself, but the tiny stitching overall needs to be carried out with precision to reach a satisfactory result. It must also be noted that the preferred 19th century cotton qualities were even finer and denser, which resulted in a higher degree of difficulty.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka (Historical Reproduction/Embroidery).

- Lundbäck, M., Ingers, G. & Ljungkvist, E., Hemslöjdens Handarbeten – Andra delen, Stockholm 1954.

- Melén, L., Landskapssömmar, Västerås 1970.

- DigitaltMuseum: (including many examples of ‘Svartstick’ embroideries kept in Swedish museums).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE