ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– and a Case Study of Swedish Knitting Traditions

The earliest knitting in the Nordic area can be traced to the 16th and 17th centuries. Foremost, via archaeological fragments and extant luxury silk garments – sometimes in combination with gold or silver threads – and artworks depicting wealthy individuals in knitted sweaters or waistcoats. This essay, however, will focus on the following centuries, at a time when the technique had become widespread in the southern half of Sweden. Clothes kept in museum collections, contemporary travel journals, local descriptions, paintings, early photographs and a reproduction of a knitted cap have been part of my research. These traditions give a multitude of aspects connected to domestic economies, trade and selling of knitted goods, women’s work and overall textile handicraft, which in some restricted geographical areas developed into highly skilled crafts, on an almost industrial scale in a cottage environment.

This interior of a manor house illustrates two young female servants, circa 1775, which gives a detailed understanding of everyday tasks like ironing a linen shirt as well as knitting. For this case study, the knitting in the round with four needles is of particular interest. The seated woman appears to work on a single coloured white coarse wool sock, a type which was preferred for best durability, lowest cost due to that it was un-dyed and uncomplicated to knit in one colour only. Just as today, socks easily became worn out and either had to be renewed or at least the heel-foot-toe part to be re-knit. To my knowledge however, no such socks of an ordinary model, which evidently originate from the 18th century have been preserved up to the present time. (Oil on canvas by the artist Pehr Hilleström (1832-1816) at Näs manor house, province of Upland. (Sold by Bukowskis Classical auction 589, unknown ownership).

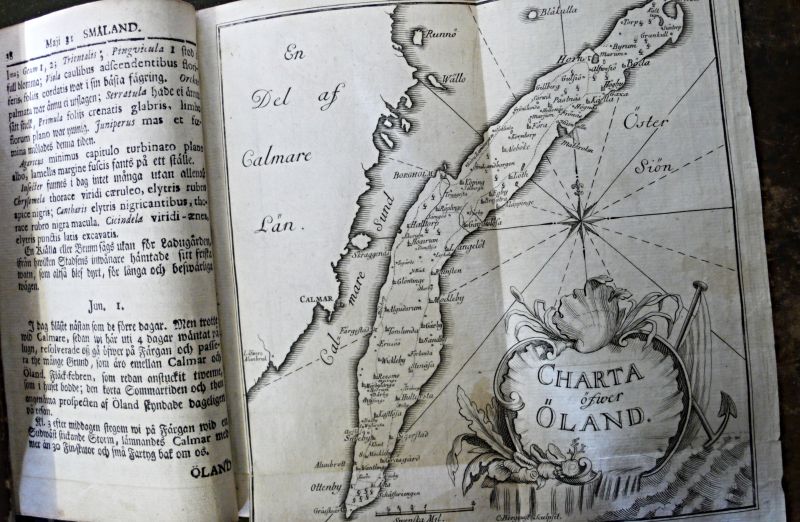

This interior of a manor house illustrates two young female servants, circa 1775, which gives a detailed understanding of everyday tasks like ironing a linen shirt as well as knitting. For this case study, the knitting in the round with four needles is of particular interest. The seated woman appears to work on a single coloured white coarse wool sock, a type which was preferred for best durability, lowest cost due to that it was un-dyed and uncomplicated to knit in one colour only. Just as today, socks easily became worn out and either had to be renewed or at least the heel-foot-toe part to be re-knit. To my knowledge however, no such socks of an ordinary model, which evidently originate from the 18th century have been preserved up to the present time. (Oil on canvas by the artist Pehr Hilleström (1832-1816) at Näs manor house, province of Upland. (Sold by Bukowskis Classical auction 589, unknown ownership). The island of Öland was the place where knitting caught the naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) attention, perhaps mainly because the women knitted stockings while out walking or doing other chores. This map of Öland was included in his travel journal from the summer of 1741, printed four years later. (Collection: Lund University Library, Special Collection. Linnaeus… 1745). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The island of Öland was the place where knitting caught the naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) attention, perhaps mainly because the women knitted stockings while out walking or doing other chores. This map of Öland was included in his travel journal from the summer of 1741, printed four years later. (Collection: Lund University Library, Special Collection. Linnaeus… 1745). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.On 18 June 1741 from this island, Linnaeus wrote in his travel journal: ‘The women-folk here in this place were everywhere seen to be busying themselves, having usually in their hand a stocking with needles for knitting’. Or the seemingly impossible combination: ‘The women-folk who drove stones with oxen, knitted continuously on their stockings, although they held the reins during the actual driving’. The production of knitted articles was substantial on the islands of Öland and Gotland, according to written sources from the time, whereas only a limited number of items are still extant. That fact would indicate that the knitting women whom Linnaeus studied chiefly produced everyday garments which gradually wore out, eventually to be used as rags or otherwise re-used. The wool yarn of the garments could be unravelled and be used again for new stockings in the poorer homes. The Öland women as diligent knitters of stockings was widespread, but there was also proof of more refined knitting. That was, for instance, noticed at Högsby on 14 June among the church-going people dressed in their Sunday bests. Some women wore a neck-cloth which was ‘knitted with silk edges’.

Later on this summer, during his visit to the island of Gotland the knitted garments were admired, as they had been in Öland: ‘Jackets here generally worn by the peasants, which resembled jackets of worsted yarn, were usually neatly adorned with white, blue and red colours, as if they had been woven, whereas they had been knitted by the peasant women’s hands.’ (28 June 1741) Knitting beautifully patterned jackets/sweaters was not something generally developed in very many places in Sweden in the 1740s and seemed to have been a novelty for Linnaeus.

Some years later, during his journey to the southernmost province of Skåne in 1749, he also noticed some details of knitted garments for women and men. For instance, on Sunday 14 May in Virestad, Småland, the married women in the farming community wore a small basin-shaped knitted garment of white wool which was wound around the gathered hair at the nape. Some days later, when reaching the village of Sinclairsholm, he noted that men wore blue knitted finger gloves as part of their festive costume.

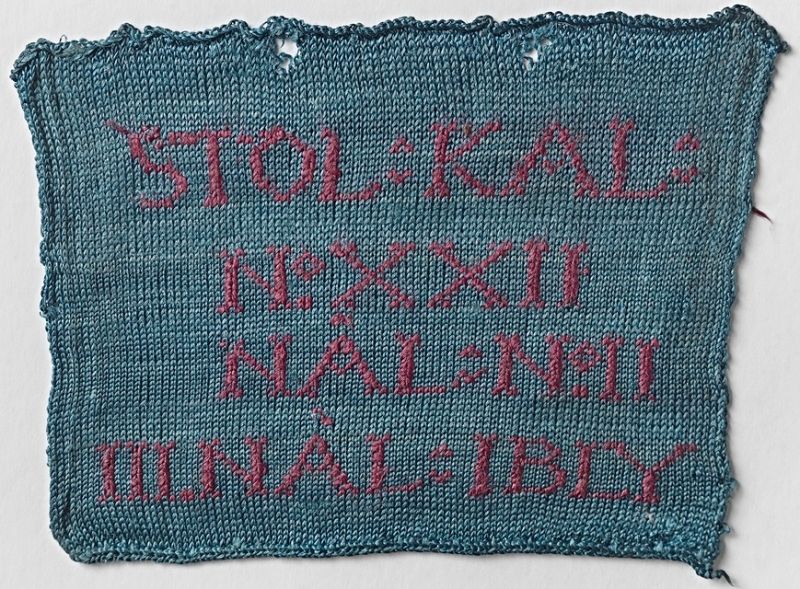

Even if machine-knitted garments still were quite rare in mid-18th century Sweden, it existed and in particular in use for luxurious very fine silk stockings. The technique is illustrated here with one of six machine-knitted samples, originating from an unknown Swedish manufacturer, circa 1740s-1760s. This knitted sample of silk, was done in stocking stitch with a knitted letters in a contrasting colour. According to the Nordic Museum research group, the knitted letters had the following meaning: ‘STOL means stocking loom. KAL plus Roman numeral means the calibre number and thus indicates the fineness of the machine. III NÅL IBLY means three needles per lead. Roman numeral II means two needles per lead. Only those looms with three needles per lead were considered to produce fine quality.’ (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NM.0017648B.145. Digitalt Museum).

Even if machine-knitted garments still were quite rare in mid-18th century Sweden, it existed and in particular in use for luxurious very fine silk stockings. The technique is illustrated here with one of six machine-knitted samples, originating from an unknown Swedish manufacturer, circa 1740s-1760s. This knitted sample of silk, was done in stocking stitch with a knitted letters in a contrasting colour. According to the Nordic Museum research group, the knitted letters had the following meaning: ‘STOL means stocking loom. KAL plus Roman numeral means the calibre number and thus indicates the fineness of the machine. III NÅL IBLY means three needles per lead. Roman numeral II means two needles per lead. Only those looms with three needles per lead were considered to produce fine quality.’ (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NM.0017648B.145. Digitalt Museum).Another close observer of hand knitting was Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) – one of Carl Linnaeus’ former students – who lived in the southern part of the province of Halland from 1758 until his death in 1805. From that period and until the publication of his book Utkast til beskrifning öfver Laholms Prosteri (Outlines of a description of the Deanery of Laholm) in the year 1796, he collected material about customs and traditions, plants and general conditions of life in the area. It was to be a book which was in a sense in accordance with Linnaeus’ regional accounts, but from a somewhat different perspective. Osbeck’s observations about everyday life in a limited geographical area over a longer period were more detailed, even including studies of spinning materials, knitting and weaving with notes on how the rural population dressed. The greatest focus was placed on the intensive activity of knitting in the area, a craft which contributed towards that many people earned an extra income and with that a better existence in the poor and barren landscape. In recent decades, a manuscript in Osbeck’s own hand on natural history and animals of the rural deanery of Laholm has been published (Djur och Natur i Södra Halland under 1700-talet). One can read about the sheep in the area, which he regarded as too few in number, resulting in an insufficiency of wool available to buy in the district. Large quantities were therefore bought in from the province of Skåne for the extensive knitting of stockings, especially the finer kinds of wool. Wool, as well as sheepskin, were even imported from Denmark and Iceland in order for the intensive production of knitted items to continue.

Pehr Osbeck seemed to admire the local women’s industriousness while at the same being surprised that they managed to live into their 70s, 80s and 90s having worked so hard all their lives. They manured, raked, baked, cooked, brewed, washed, worked for the big house, tended children and whenever there was a moment to spare, they knitted without cease while sitting down as well as on their way to some errand. He established that the production of knitted stockings stretched from the ridge of Hallandsåsen to the parish of Laholm. In that the southernmost part of Halland, the knitting of stockings was in fact considered to be the most profitable line of work. He argued that the intensive production originated on the Wallen’s Estate, where part of the dues entailed knitting stockings for the estate. Although the women were the ones most industriously busy with that work, the entire family was involved with everything from carding, spinning and knitting to fulling. His view is reinforced by Per Göran Johansson’s research into knitting in Halland, which demonstrates that land registers from 1759 confirm the statement that the peasants who were exempt from dues had to knit stockings for the estate every year. That consisted of 60 kg wool, approximately enough for 200 pairs of stockings. Estate inventories from the same year recorded that the Wallen’s Estate had 238 kg wool, sorted into various qualities, all ready to be distributed among the peasants for knitting stockings for the estate. Sven T. Kjellberg’s archival studies also indicate that the contemporaries M. Tornberg 1766 and H. P:son Agard 1777 were registered for privileges as makers of carding-combs at Laholm. Carding-combs were indispensable implements for the preparation of wool, and the production by those local manufactures must have been considerable, given the industrial scale of the knitting in the district.

Pehr Osbeck also noted that people held bees where they gathered to knit, something described as follows: ‘At these gatherings the mouth is constantly in as much motion as the knitting needles. Among such persistent fluttering, a good deal of vexatious and mendacious talking can hardly be avoided.’ He also wrote that ‘Womenfolk carry their stockings with them wherever they go, to the catechetical meetings in the homes, to the church where they leave them in the porch, until they come out again; but the men folk leave their stockings at home.’ He reacted against a constant clattering of the knitting needles too as soon as he got anywhere near a woman, and the children were trained at as early an age as 6-8 to be able to assist with the income-yielding activity. Knitting did not only bring in a good income for the peasants but also for the poorer people in society. Assessor Pettersson of Laholm was described as a benefactor, handing out wool to the poor who knitted stockings against payment. They carded, spun, knitted and finally fulled the material to make the stockings stronger and warmer. The foot itself was often made of a coarser type of wool to prolong its life further. Once a considerable quantity of stockings had been knitted, they were collected by tradesmen, usually itinerant pedlars, to be sold on in bigger towns, sometimes as far north as Norway. The military of various regiments were great consumers of the stockings from Halland. Osbeck recorded that ‘the year 1765 yielded 24,000 pairs of stockings and during the last war in Finland the peasants disposed of their goods entirely’. From that, it can be extrapolated that the needs of the military alone for one single year must have meant that nearly 1,000 people were involved in the carding, spinning and knitting of those stockings. Such great knitting activity in the area must, therefore, have originated several decades prior to the 1750s for it to have spread and engaged so many people by then.

The province of Halland had not only a knitting tradition of woollen stockings and sweaters used by several strata of society during the second half of the 18th century, but also much finer cotton garments, knitted in purls of eight-pointed stars and diamond shape motifs. Like this well-preserved example dating circa 1750-70. Such a jersey styled garment however, was probably part of a well-to-do woman’s clothing, due to that cotton at this time was regarded as luxury goods and the design has similarities with upper class fashions. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NM.0127422. Digitalt Museum).

The province of Halland had not only a knitting tradition of woollen stockings and sweaters used by several strata of society during the second half of the 18th century, but also much finer cotton garments, knitted in purls of eight-pointed stars and diamond shape motifs. Like this well-preserved example dating circa 1750-70. Such a jersey styled garment however, was probably part of a well-to-do woman’s clothing, due to that cotton at this time was regarded as luxury goods and the design has similarities with upper class fashions. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NM.0127422. Digitalt Museum). The knitting tradition in the province of Halland continued during the 19th century and became known for its rich combinations of motifs in red, blue and white. At the end of that century the textile craft declined, but from 1907 it got a renaissance via the newly founded handicraft organisation in Laholm by Berta Borgström et al. She organised local women and some men, knowledgeable in the tradition to knit such wool garments and the readymade sweaters, socks, hats etc. were sold. Designs were copied or redesigned and rapidly became immensely popular, not only in the local area. Here illustrated at the Stockholm exhibition in 1909, where the multi-coloured knitting or “binge” was demonstrated by the couple, Lars Petter and Beata Jönsson from the Halland. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NMA.0034471. Digitalt Museum).

The knitting tradition in the province of Halland continued during the 19th century and became known for its rich combinations of motifs in red, blue and white. At the end of that century the textile craft declined, but from 1907 it got a renaissance via the newly founded handicraft organisation in Laholm by Berta Borgström et al. She organised local women and some men, knowledgeable in the tradition to knit such wool garments and the readymade sweaters, socks, hats etc. were sold. Designs were copied or redesigned and rapidly became immensely popular, not only in the local area. Here illustrated at the Stockholm exhibition in 1909, where the multi-coloured knitting or “binge” was demonstrated by the couple, Lars Petter and Beata Jönsson from the Halland. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No. NMA.0034471. Digitalt Museum). Over the years, I have knitted several garments inspired by the historical knitting traditions in the province of Halland in southern Sweden, most recently this cap of 2-ply wool in the same type of colour scale that may have been used traditionally, unknown how far back in time though. Please notice, that this design is exactly the same as the man wears on the photograph from 1909 above, his cap was also a reproduction from even earlier times. (Knitting instruction, see sources: Johansson… p. 106). Photo and ownership: Viveka Hansen.

Over the years, I have knitted several garments inspired by the historical knitting traditions in the province of Halland in southern Sweden, most recently this cap of 2-ply wool in the same type of colour scale that may have been used traditionally, unknown how far back in time though. Please notice, that this design is exactly the same as the man wears on the photograph from 1909 above, his cap was also a reproduction from even earlier times. (Knitting instruction, see sources: Johansson… p. 106). Photo and ownership: Viveka Hansen.With a few concluding thoughts on hand-knitting during the 18th century and for many decades during the coming century too, this essay will emphasise that it had several advantages compared to the use of machines. It required little equipment and could be done while sitting or walking, or after dark by firelight, enabling short free moments to be used for making clothing for the family or for sale. Also, a problem with knitting clothes on stocking frames was that the process was largely standardised, allowing little room for changes in fashion, design or material. In contrast, a woman knitting by hand was freer to adopt new ideas. Hand-knitted products also had the advantage of being cheaper for the customer, since the women, children and old people who made them were paid astonishingly little. Meanwhile, frame-work knitters – like the manufacturer Jonas Alströmer’s establishment using imported knitting machines already around the year 1730 – were more expensive, since having invested money in their mechanised equipment and trained workmen.

Notice: Quotes have been translated from Swedish to English.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 121-23, 323-24 & 337).

- Hansen, Viveka (Reproduction: knitted hat in 2019, after a traditional pattern from Halland province).

- Hazelius-Berg, Gunnel, ‘Stickade tröjor från 1600- och 1700-talen’, Fataburen, pp. 87-100, 1935.

- Johansson, Britta & Nilsson, Kersti, Binge – en halländsk sticktradition, Halmstad 1980.

- Johansson, Per-Göran, Gods, kvinnor och stickning – Tidig industriell verksamhet i Höks härad i södra Halland ca 1750-1870, Lund 2001.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943 (p. 736).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa, på höga öfwerhetens befallning förrättad år 1749…, Stockholm 1751.

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd – den svenska hemslöjden fram till 1800-talets slut, Lund 1972 (pp 51-89).

- Osbeck, Pehr, Utkast til beskrifning öfver Laholms Prosteri 1796, Lund, facsimile 1922.

- Osbeck, Pehr, Djur och Natur i Södra Halland under 1700-talet (after a manuscript), Halmstad 1996.

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990 (p. 207 & quote p. 260).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE