ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

IN THE TEXTILE DOWRY

– Woven Zigzag Designs on Double Interlocked Tapestries from 1700 to 1850

Colourful compositions named zigzag, wave or lightning patterns in the weaving technique double interlocked tapestry or rölakan were initially used during festivities or special occasions as either cushions, benches- or bedcovers from circa 1700 to 1850. Most of the year, such textile treasures were stored in chests, which kept the fabrics well preserved and colours unfaded. Long-lasting traditions, the usefulness of the textiles and the creation of large dowries – woven within the household before the young woman’s wedding – are the three most important factors in the increased production of decorative textiles in the farming communities of southernmost Sweden. This essay is part of an in-depth research of almost 1,700 double-interlocked tapestries in textile collections in northern Europe.

![This design with its zigzag border woven in double interlocked tapestry (rölakan) – is a rare combination of motifs from Torna district in the Skåne province. During my research of this Swedish tapestry type (1984-1991), a few cushions only were similar in style even if no two were identical. However, at some moment in time this carriage cushion or bench cover was cut/reduced in size, but the initials and year ‘EAD 1808’ [D = dotter/daughter] give some clues to its history. The complex tapestry was handwoven with naturally dyed wool on linen warp during the year 1808, probably by the young woman herself prior to her wedding or by her mother or other female relative. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, Hemslöjden Collections. MSSH-0060. Digitalt Museum).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-rolakan-1808-664x718.jpg) This design with its zigzag border woven in double interlocked tapestry (rölakan) – is a rare combination of motifs from Torna district in the Skåne province. During my research of this Swedish tapestry type (1984-1991), a few cushions only were similar in style even if no two were identical. However, at some moment in time this carriage cushion or bench cover was cut/reduced in size, but the initials and year ‘EAD 1808’ [D = dotter/daughter] give some clues to its history. The complex tapestry was handwoven with naturally dyed wool on linen warp during the year 1808, probably by the young woman herself prior to her wedding or by her mother or other female relative. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, Hemslöjden Collections. MSSH-0060. Digitalt Museum).

This design with its zigzag border woven in double interlocked tapestry (rölakan) – is a rare combination of motifs from Torna district in the Skåne province. During my research of this Swedish tapestry type (1984-1991), a few cushions only were similar in style even if no two were identical. However, at some moment in time this carriage cushion or bench cover was cut/reduced in size, but the initials and year ‘EAD 1808’ [D = dotter/daughter] give some clues to its history. The complex tapestry was handwoven with naturally dyed wool on linen warp during the year 1808, probably by the young woman herself prior to her wedding or by her mother or other female relative. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, Hemslöjden Collections. MSSH-0060. Digitalt Museum).Eye-dazzling designs similar to these have been used on textiles for many centuries, in embroidery and weaving alike. Some examples are figure woven silks during the 14th and 15th century Moorish Spain, Florentine flame stitch or Bargello needlework originally used for 17th century upholstering of chairs in Firenze (Florence) or kilim tapestries from south Persia or copied into motifs in Flemish artworks. In southernmost Sweden during the 18th century and up to circa 1850, this type of design seems to have been increasingly popular over the period. In the double interlocked tapestry – a technique making the linen warp completely hidden – various zigzag combinations were gradually adopted to finer lines and a more tapestry-like appearance. A common way of demonstrating one’s skill as a weaver was by getting closer to the highly desired tapestry weaving but still using the ordinary, more time-effective horizontal loom. Therefore, the female weavers in the better-off farming districts produced finer and finer qualities of such patterning over the period 1820s to 1850s.

![One of the motifs depicted in ‘Buratto, a Book of Embroidery’ printed in 1527 is this centred wave or zigzag design. Such printed books for embroidery in the 16th and 17th centuries, have been regarded as important sources of inspiration for well-to-do households of the nobles, bourgeoise and priests who could afford to buy books. Later on in the 18th century, similar combinations of motifs were also spread to women in the farming communities. Either via preserved books, designs copied on to paper or other material or by direct contact with ready-made textiles – which all could influence and give ideas for embroidery as well as for art woven techniques like “rölakan”. (From: Paganino, Alessandro, Il Burato, Libro de Recami, 1527 [1518], p. 58).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-p-58-664x451.jpg) One of the motifs depicted in ‘Buratto, a Book of Embroidery’ printed in 1527 is this centred wave or zigzag design. Such printed books for embroidery in the 16th and 17th centuries, have been regarded as important sources of inspiration for well-to-do households of the nobles, bourgeoise and priests who could afford to buy books. Later on in the 18th century, similar combinations of motifs were also spread to women in the farming communities. Either via preserved books, designs copied on to paper or other material or by direct contact with ready-made textiles – which all could influence and give ideas for embroidery as well as for art woven techniques like “rölakan”. (From: Paganino, Alessandro, Il Burato, Libro de Recami, 1527 [1518], p. 58).

One of the motifs depicted in ‘Buratto, a Book of Embroidery’ printed in 1527 is this centred wave or zigzag design. Such printed books for embroidery in the 16th and 17th centuries, have been regarded as important sources of inspiration for well-to-do households of the nobles, bourgeoise and priests who could afford to buy books. Later on in the 18th century, similar combinations of motifs were also spread to women in the farming communities. Either via preserved books, designs copied on to paper or other material or by direct contact with ready-made textiles – which all could influence and give ideas for embroidery as well as for art woven techniques like “rölakan”. (From: Paganino, Alessandro, Il Burato, Libro de Recami, 1527 [1518], p. 58). A detail of this Trompe-l’œil dating 1671 – a technique in art giving an optical illusion of a three dimensional perspective – by the Flemish artist Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts (c.1630-c.1675), includes a clearly identifiable zigzag ornamented design. This holder used for keeping all sorts of valuable small objects, probably depicted a tapestry woven or embroidered textile. If the colourful zigzag motif was added for a splendid effect only on the painting or if copied from a similar object in real life is unknown, but even so, zigzag or flame designs must have been well known in the Flemish area at this time. (Collection: National Gallery of Denmark… part of KMS1902). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

A detail of this Trompe-l’œil dating 1671 – a technique in art giving an optical illusion of a three dimensional perspective – by the Flemish artist Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts (c.1630-c.1675), includes a clearly identifiable zigzag ornamented design. This holder used for keeping all sorts of valuable small objects, probably depicted a tapestry woven or embroidered textile. If the colourful zigzag motif was added for a splendid effect only on the painting or if copied from a similar object in real life is unknown, but even so, zigzag or flame designs must have been well known in the Flemish area at this time. (Collection: National Gallery of Denmark… part of KMS1902). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Knowledge about weaving traditions in the farming communities in southernmost Sweden before the year 1700 is very limited due to few preserved estate inventories and actual physical objects originating from this stratum of society. However, early traces of such information from the bourgeois and priesthood are much more frequent. Already in the mid-16th century, so-called Flemish tapestries or dove-tail tapestries are listed in various such inventories. When a technique or pattern had been established in a geographical area, these slowly but steadily seem to have been inspired by interconnections between the social classes. Established routes could be:

- nobility – bourgeois – priesthood – farmers

- nobility – priesthood – bourgeois – farmers

- bourgeois – priesthood – farmers

- priesthood – bourgeois – farmers

Priest daughters being married to better-off farmers is believed to have been a particularly important way for the distribution of new pattern combinations for double interlocked tapestries – among other art woven and embroidered textiles during the 17th and 18th centuries. Not all inspirational factors are known, but there is evidence that all strata of society were part of an ongoing development of pure ornamental or symbolic pattern designs alike. The difference is that progression has gone in diverse directions, from nobility, bourgeois, priest homes, and farming communities over several hundred years. Due to this reality, the same or very similar motifs appeared and disappeared over longer or shorter periods, and each stratum of society as well as depending on one’s geographical location (hardy visible in noble families), had a further impact on the continuous sharing of designs for fine zigzag surfaces and borders among a myriad of other pattern combinations.

Well-preserved early 19th century square-shaped cushion in perfectly symmetrically woven zigzag motifs. Handwoven in the double interlocked tapestry technique on a linen warp and woollen weft. Pieces of wadmal cloth strengthened and decorated the corners, whilst traces of down remains within the cushion. Woven in Östra Göinge district, Skåne province, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0040184, front. Digitalt Museum).

Well-preserved early 19th century square-shaped cushion in perfectly symmetrically woven zigzag motifs. Handwoven in the double interlocked tapestry technique on a linen warp and woollen weft. Pieces of wadmal cloth strengthened and decorated the corners, whilst traces of down remains within the cushion. Woven in Östra Göinge district, Skåne province, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0040184, front. Digitalt Museum). The back of the same cushion, demonstrates the same perfection by the weaver. As customary the back was outlined in a “simpler” style however, here in a weft ribbed technique. This way of designing a cushion, meant that the shuttle could be in constant use making it quicker to weave, contrary to the complex zigzag front which was made like a tapestry when the weaver manually had to interlace each woollen colour to its designated area. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0040184, back. Digitalt Museum).

The back of the same cushion, demonstrates the same perfection by the weaver. As customary the back was outlined in a “simpler” style however, here in a weft ribbed technique. This way of designing a cushion, meant that the shuttle could be in constant use making it quicker to weave, contrary to the complex zigzag front which was made like a tapestry when the weaver manually had to interlace each woollen colour to its designated area. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0040184, back. Digitalt Museum).There could be several festivities and celebrations during the year, but when a wedding took place, this was one of the more essential occasions in a family’s life, an event which had been prepared during years of collecting, weaving and embroidering for the daughter’s dowry. Double interlocked tapestries – rölakan were often included as treasured possessions that not only had economic value but also gave the family a particular status at the moment. These textiles also had considerable value in the long term and became possible to inherit through several generations. This was because said textile belongings, most of the time, were kept in chests and were given an airing but otherwise kept out of the sunlight and stored away. With this in consideration, one’s interior decorative textiles got slight wear and tear; for example, the colours of the wool were almost preserved unchanged through the years. Also, many farmers’ textile storages steadily increased in size, becoming more prominent with each generation.

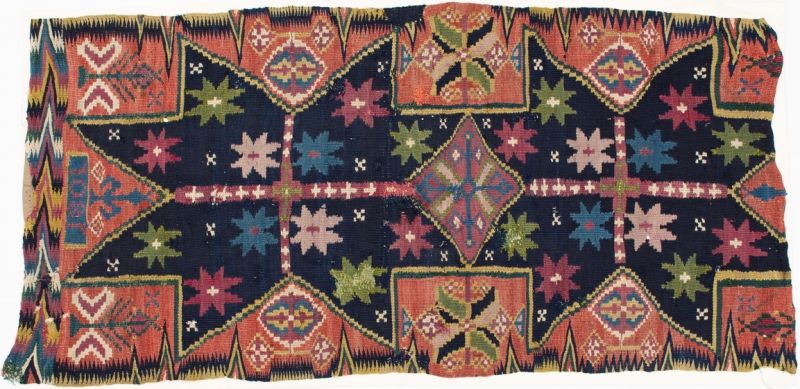

Another example is the so-called “Skytts star” from Skytts district in the Skåne province, woven in an intricate combination of stars and tree of life motifs. Zigzag ornamentations were often included to finalise and decorate the edges of such furnishing textiles. Similar in style as may be studied on this somewhat fragmented cushion in double interlocked tapestry dating 1801 on linen warp with woollen weft, which belongs to a group of only six examples, possible to trace of this particular design. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, Hemslöjden Collections. MSSH-0055. Digitalt Museum).

Another example is the so-called “Skytts star” from Skytts district in the Skåne province, woven in an intricate combination of stars and tree of life motifs. Zigzag ornamentations were often included to finalise and decorate the edges of such furnishing textiles. Similar in style as may be studied on this somewhat fragmented cushion in double interlocked tapestry dating 1801 on linen warp with woollen weft, which belongs to a group of only six examples, possible to trace of this particular design. (Courtesy of: Stiftelsen Skånsk Hemslöjd, Hemslöjden Collections. MSSH-0055. Digitalt Museum).The zigzag motifs were the most common combination of patterns for rölakan textiles. In the inventory, these designs were traced to be a main feature on 153 examples or almost 10% – divided into 68 carriage cushions, 55 square-shaped cushions, 14 bench covers, 11 bedcovers and five fragmented pieces. The type was common in the entire province of Skåne (southernmost Sweden) and also existed to a lesser extent in a few other provinces. Furthermore, minor zigzag motifs were included in a wide selection of other designs within the same geographical area, dominantly as borders. A closer examination of such a large number of textiles reveals how strictly the weaver, in the main, kept to the traditional designs but simultaneously put their own individual character on each cushion with minor unique elements. This could effectively be achieved with small figure details running down the centre surrounded by a zigzag background, covering the entire surface with a slightly changed colour scale, or using border designs that seem to have been endless inspiration.

Sources:

- Fischer, Ernst, Skånska yllebroderier i fria sömsätt, Malmö Museum 1971 (pp. 22-23).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets konst och kulturhistoria, Christinehof 1992 (pp. 16, 29, 105, 121-128 & 249-251).

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art , London 1996.

- Hansen, Viveka, (Inter-foliated multi language edition; with Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets konst och kulturhistoria, 1992), London 2019.

- National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen (Visit the galleries in December 2018).

- Textile Research Centre, Leiden (Online source): Information about Alessandro Paganino & the pattern book: Il Burato, Libro de Recami (1527/Facsimile 1909).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE