ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

ITALIAN SILKS AND VELVETS

– Medieval Textiles

Lucca, Genova, Firenze, Venezia, and Milano are cities where silk weaving developed into a work of art during the Medieval period and Renaissance. These desirable textiles were sold via a myriad of trading routes through Europe and beyond. St Petri church in Malmö was one such customer, who aspired to extend its storage of vestments, especially during the 15th century and up to the Reformation. The aim of this fourth text of the collection is to give a brief history of Italian silks and their weaving traditions. Close-up photographs of selected silk and velvet fragments intend to illustrate motifs further, as well as preferred colours and the former uses for these sought-after textiles, not only by churches and cathedrals but to the same extent by the wealthy citizens who wished to be fashionable in clothing, as well as for textile interiors in their homes.

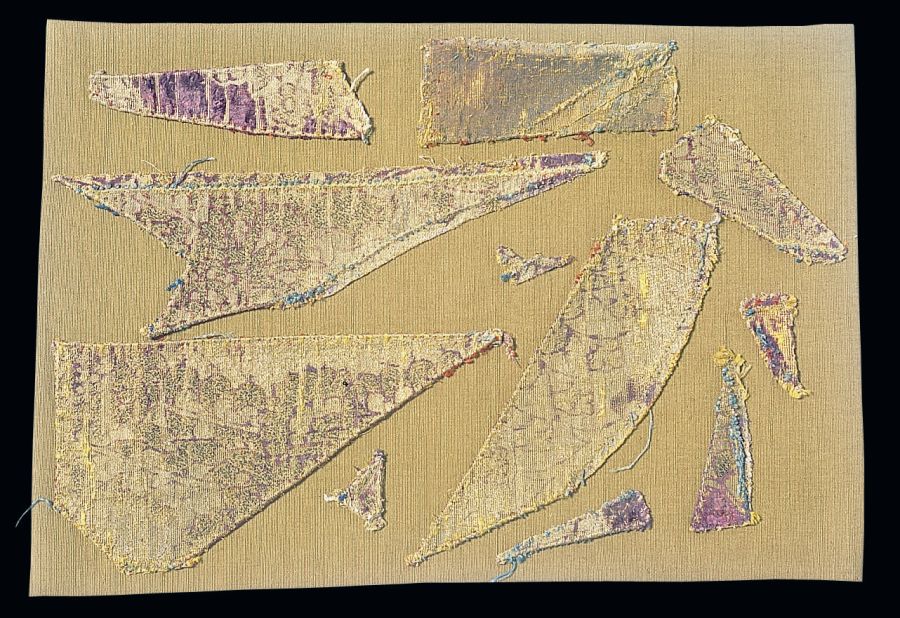

These ten fragments are some of the pieces left which are once believed to have been part of a 15th century chasuble. For this vestment an exquisite Italian silk with originally deep red pomegranates and shining membrane gold was used – today purple in colour and darkened metallic threads. Largest width, 68 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

These ten fragments are some of the pieces left which are once believed to have been part of a 15th century chasuble. For this vestment an exquisite Italian silk with originally deep red pomegranates and shining membrane gold was used – today purple in colour and darkened metallic threads. Largest width, 68 cm. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.The competition was fierce between the weaving centres, particularly in the city-states of Lucca, Genoa, Florence, Milan and Venice. Several towns managed to develop an individual style of their own in patterns and silk qualities, but these trading secrets were hard to keep and spread quite rapidly to surrounding areas. The late textile historian Agnes Geijer emphasised that at the same time as the weavers took great care of their family’s traditional designs, they were often equally interested in being up-to-date with inventions and methods from nearby workshops. These circumstances resulted in the complex patterned silks and velvets from various weaving centres gradually appearing to be more and more similar and finally, during the 15th century, it became almost impossible to identify local differences in designs, colour preferences or other characteristics.

However, less successful attempts to keep local knowledge within certain city-states were made in the 15th century. For example, in July 1440, it became illegal to move looms or other weaving equipment from Genoa, at the same time as several areas had restrictions for the weavers’ movements. In theory, this meant that silk weavers could only work where they were once trained, but this prohibition had limited effects. Two reasons were that weavers from Genoa moved and started up their own silk workshops in Milan or Ferrara or that Venetian weavers moved abroad.

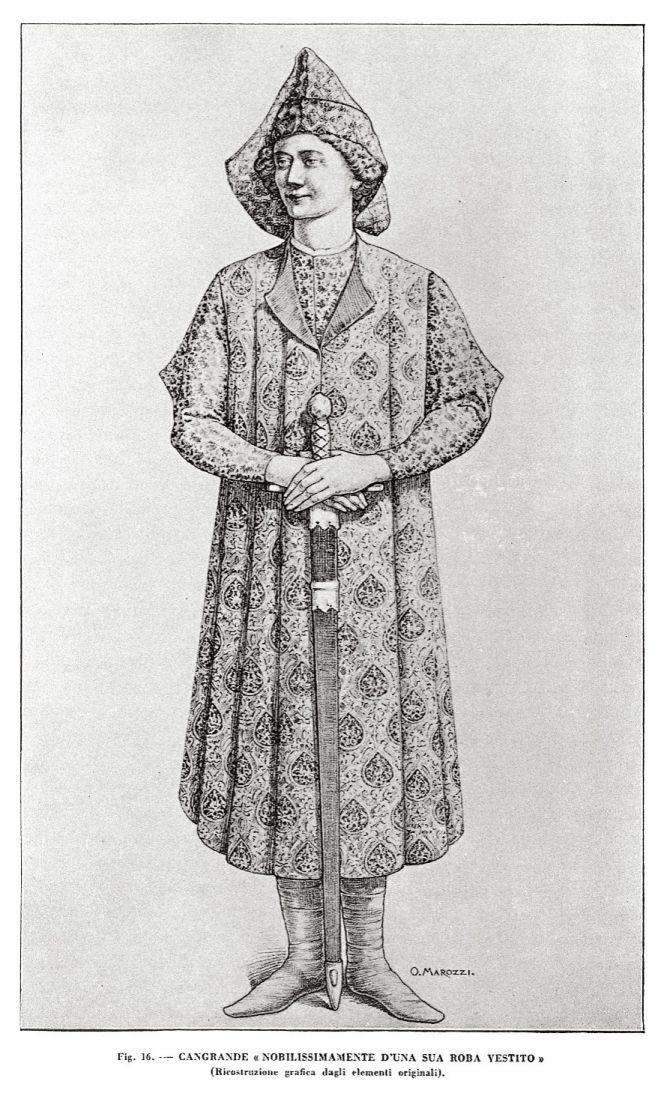

Medieval portraits is a vital primary source for the study of fabrics/motifs of clothes and other textiles. All those who could afford a silk brocade with for example a pomegranate design like this was; the church, nobles, monarchs who sought to own these luxurious textiles. This particular motif can be traced throughout history, but it reached great popularity in Italy during the 14th to 16th centuries, both within ecclesiastic and noble spheres, an example of this can be seen here in this portrait of a young nobleman in the 14th century. (Sangiorgi, Giorgio, Contributi allo studio dell’arte textile, Roma 1920).

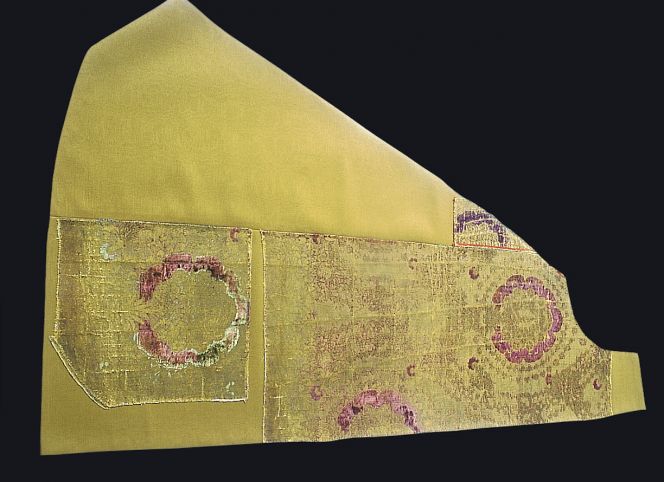

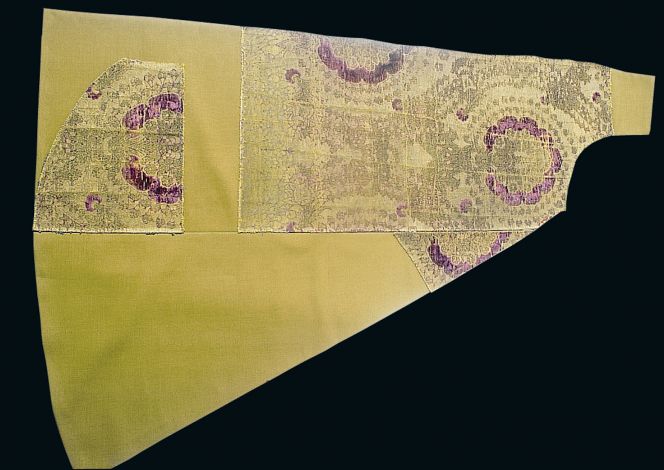

Medieval portraits is a vital primary source for the study of fabrics/motifs of clothes and other textiles. All those who could afford a silk brocade with for example a pomegranate design like this was; the church, nobles, monarchs who sought to own these luxurious textiles. This particular motif can be traced throughout history, but it reached great popularity in Italy during the 14th to 16th centuries, both within ecclesiastic and noble spheres, an example of this can be seen here in this portrait of a young nobleman in the 14th century. (Sangiorgi, Giorgio, Contributi allo studio dell’arte textile, Roma 1920). On this partly preserved profane coat in the St Petri collection, dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, the pomegranate motif is present just as on the portrait above. The more than thirty fragments were reconstructed by textile conservator Margaretha Nockert in the early 1980s in order, to demonstrate the probable shape of the coat…

On this partly preserved profane coat in the St Petri collection, dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, the pomegranate motif is present just as on the portrait above. The more than thirty fragments were reconstructed by textile conservator Margaretha Nockert in the early 1980s in order, to demonstrate the probable shape of the coat… The garment is regarded to have been very loose fitting (300 cm in circumference) with long wide sleeves and reaching down to the feet. The largest fragment is 47 cm wide and 103 cm long, here illustrated in two separate images. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

The garment is regarded to have been very loose fitting (300 cm in circumference) with long wide sleeves and reaching down to the feet. The largest fragment is 47 cm wide and 103 cm long, here illustrated in two separate images. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Some weaving workshops in the Italian city-states were family businesses while others were more extensive manufacturers, but all together, silk weaving developed into a major trade and wide-ranging export. As mentioned earlier, it was not only European churches that purchased Italian silks and velvets; everyone who could afford such luxury qualities was a potential customer. For example, in accounts and estate records (1325-1462) from England, it is possible to localise that the Royal household imported silks of Italian origin, a trade often carried out via the town of Bruges [Brugge]. The late Donald King, historian and keeper of textiles at The Victoria and Albert Museum, specialised in these fabrics and particularly in the silks from Lucca. In research based on studies from Lucca, King also emphasised that the silk weaving in this city-state reached its peak during the 13th century. However, the production probably started before the year 1000, and similar exquisite qualities were still much sought-after in the early 15th century.

One of the most famous techniques diasprum [diasper] – a complex double silk weave – was woven in one or two colours and often added with metallic threads of gold and silver. Family names connected to this famous silk weaving in Lucca were Buonvisi, Cenami, Fatinelli, Guidiccioni, Guinigi, Sercambi, Spada and Trenta. These long-lasting weaving families are believed to have been the foundation, not only for the large domestic production but also for the extensive export to the countries in Northern Europe, among other places. Their exquisite silk fabrics also inspired many more families in nearby areas to master this lucrative craft, and eventually, Spanish workshops started to “imitate the art of weaving from Lucca”.

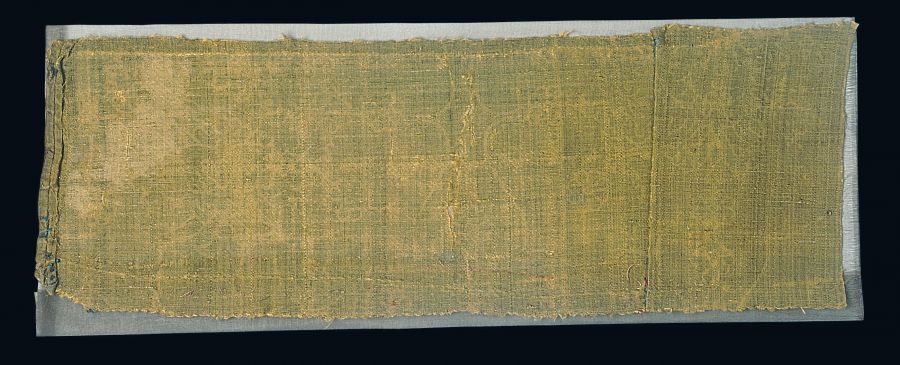

Italian gold and silk brocade – a quality which has lost some of its former glory due to its darkened membrane gold – probably part of a chasuble or cope in the Medieval St Petri church. The fabric was woven in the 15th century. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Italian gold and silk brocade – a quality which has lost some of its former glory due to its darkened membrane gold – probably part of a chasuble or cope in the Medieval St Petri church. The fabric was woven in the 15th century. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.During the 14th century, the Venetian silk weavers were seen as equal to the master craftsmen in Lucca, and this century also became the starting point in Venice and other places for a style more inspired by the East. Agnes Geijer called this style the “free” or “wild” with its flying birds, Chinese dragons, irregular flower compositions and jumping deers in contrast to the previous use of strict geometrical patterns. However, early on in the coming century, stricter ideals were once again preferred, with pomegranates being one of the favourite kinds of patterning on Italian silk fabrics. As already noted, several proofs of this popular motif are included in the collection of St Petri church (images 1 to 4 and on one further fragment below).

These fragments of a gold and silk brocade, have probably been used as gussets in garments. The fabric was woven in Italy during the 15th century. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

These fragments of a gold and silk brocade, have probably been used as gussets in garments. The fabric was woven in Italy during the 15th century. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Agnes Geijer’s research also pointed out that the workshops in Milan reached its peak around 1474, while the silk weaving manufacturing and trade by now involved 15,000 individuals in a population of less than 100,000. To a great extent, they produced silk fabrics with various pomegranate patterns! Metallic threads or so-called membrane gold or silver were equally important for the weft of these fabrics. The use of gold and silver threads not only gave the textiles a luxury aura, but strengthened the desired visual effects in the weaving techniques. The weaving was not only technically complex, but the thinness of the warp, as well as the weft, pushed the craft to the limit of what was possible. The production of the valuable textiles was clearly a team effort: purchase of the best raw material, spinning, pattern designs, warping, the preparation of the loom, the weaving and finally, the commercial side with possible advertising, correspondence and selling of each and every metre of fabric.

The master weaver was assisted by an apprentice boy sitting on the top of the loom, who pulled selected warp threads at the right moment after the weaver's instructions. Since the early 15th century, the weaving width was standardised to 60-70 cm, mainly due to the increasing complexity of the patterning of the silks and often even more advanced cut and uncut velvets.

This brownish fabric – originally red in colour and part of an altar cloth dating from circa 1500 – is a good example showing that velvets could also be plain in structure. Additionally, the Apostles – Paul to the left with his attribute “the sword” and Peter to the right with his “keys” – are depicted in traditional silk and gold laid work. Biblical motifs in embroidery connected to the Medieval textile collection of St Petri church, will be the theme for the next essay in this series. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This brownish fabric – originally red in colour and part of an altar cloth dating from circa 1500 – is a good example showing that velvets could also be plain in structure. Additionally, the Apostles – Paul to the left with his attribute “the sword” and Peter to the right with his “keys” – are depicted in traditional silk and gold laid work. Biblical motifs in embroidery connected to the Medieval textile collection of St Petri church, will be the theme for the next essay in this series. Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of St Petri church textiles, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Kyrkliga textilier i Malmö – från medeltid till barock’, Elbogen pp. 61-135. 2000.

- St Petri Church, Medieval Church Collection, Malmö, Sweden (researched in 1999 & 2000 for the above article. If not otherwise stated, all textile fragments are part of the St Petri collection).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE