ikfoundation.org

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

ESSAYS |

JET AND DRESSED IN BLACK

– The Victorian Period

Mourning traditions and dressed in black have been described from several angles in my book The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914, which will here be exemplified by two short capes kept at Whitby Museum, advertisements from the local newspaper, censuses and a photograph showing a jet workshop from the 1890s. It may be noted that the jet industry had a very long history, but it was never more prominent than around 1870 when they employed more than 800 people in Whitby. Expensive black clothing and other accessories included in the mourning trade were often also decorated with jet – originally manufactured in Whitby – and later stitched onto ready-made garments purchased locally or from specialist shops in larger cities. In this case study, this practice will be represented with Peter Robinson’s Mourning House on Regent Street in London.

A detailed picture showing the corner of a very heavy and highly decorated black cape from the period 1870s to the 1880s made from ribbed silk and lined with a dark silk. The collection contains a rich selection of garments of this kind, but this particular example of unknown origin is not only exceptionally well preserved but has larger jet ornaments than most. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, 2005/21). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

A detailed picture showing the corner of a very heavy and highly decorated black cape from the period 1870s to the 1880s made from ribbed silk and lined with a dark silk. The collection contains a rich selection of garments of this kind, but this particular example of unknown origin is not only exceptionally well preserved but has larger jet ornaments than most. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, 2005/21). Photo: Viveka Hansen.The Victorian dress collection at Whitby Museum includes a wide range of garments suitable for the various stages of mourning, including mantles, capes, collars, skirts, blouses, hats and dresses, mostly dating from the 1870s to 1890s. Especially striking is the extraordinary collection of capes and mantles, often made of velvet or satin and decorated with jet gemstones, beads, sequins, embroidery, silk ribbons and laces. Wearing black also became a fashion after the death of Prince Albert in 1861, when Queen Victoria herself continued to wear combinations of black until she died in 1901. This mourning mode directly influenced textile choice during several decades, especially among middle-aged and elderly middle-class women.

A rare study of men’s/boy’s working clothes and the daily work in a jet manufactory, circa 1890 at Haggersgate in Whitby. By this time the number of people involved in the manufacturing of jet had dropped but was still significant, whilst the earlier 1871 census demonstrated a peak with more than 800 men, women and children involved in the jet related trade in the Whitby/Ruswarp area alone. (Photo: Frank Meadow Sutcliffe).

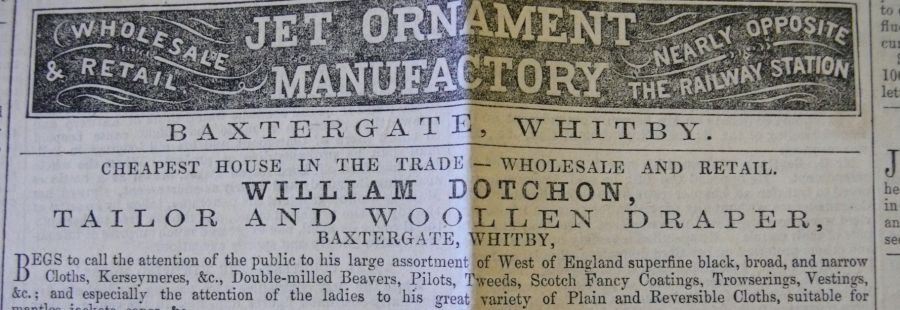

A rare study of men’s/boy’s working clothes and the daily work in a jet manufactory, circa 1890 at Haggersgate in Whitby. By this time the number of people involved in the manufacturing of jet had dropped but was still significant, whilst the earlier 1871 census demonstrated a peak with more than 800 men, women and children involved in the jet related trade in the Whitby/Ruswarp area alone. (Photo: Frank Meadow Sutcliffe). Here an example of a Jet Manufacturer who advertised in Whitby Gazette in the year 1860 with the typical “jet black” ground – printed in reversed, white on black. (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

Here an example of a Jet Manufacturer who advertised in Whitby Gazette in the year 1860 with the typical “jet black” ground – printed in reversed, white on black. (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive). Photo: Viveka Hansen.Every kind of ornamental jet jewellery finished with jet material fastened to the garment in the form of beads or stones was permissible with mourning, hence its popularity. Even some home furnishings might be decorated in this style, like an embroidered lamp shade in Whitby Museum’s Jet Collection. This is a net decorated with both small and slightly larger jet beads that could be draped over another lampshade during periods of mourning.

Label on a cape, from the mourning house ‘Peter Robinson Mantles LTD…’ in London, as described below. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, GMB2). Photo: Viveka Hansen.

Label on a cape, from the mourning house ‘Peter Robinson Mantles LTD…’ in London, as described below. (Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, GMB2). Photo: Viveka Hansen.After a year and a day, the widow could move to her second period of mourning, which still involved dressing in black, but with the most extreme black clothes, which were no longer compulsory. The dress collection includes such a late Victorian very elegant black silk cape, richly decorated with matching perforated tulle, ribbons and lace. Particularly interesting in this case is the sewn-in label: ‘Peter Robinson Mantles LTD. 256 to 262 Regent St. London’. Peter Robinson ran a well-known Mourning Warehouse founded in 1865, one of the larger establishments in what was at that time a lucrative niche, located on the capital’s most fashionable street for the mourning trade. One of the firm’s frequent advertisements promised, among other things:

‘Every requisite for Mourning Attire in the Latest Fashion kept in Stock

The First Talent in Dressmaking, and Special Orders Executed in a Day

Ladies Waited On at Home in any Part of the Country, and Travelling Expenses not Charged.’

which makes clear that exclusive garments like this could rapidly be delivered by train in Whitby and elsewhere in the country. To increase the firm’s appeal outside London, in 1876, they introduced a Book of Styles catalogue from which customers could order ready-to-wear garments to be sent by mail-order.

Sources:

- Adburgham, Alison, Shops and Shopping 1800-1914, London 1967.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (Chapter III & pp. 268-71).

- Whitby Gazette, 1855-1901 (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive).

- Whitby Museum, Costume Collection (studies of 19th century black & jet ornamented garments).

ESSAYS

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society - a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a Textile Perspective.

Open Access essays - under a Creative Commons license and free for everyone to read - by Textile historian Viveka Hansen aiming to combine her current research and printed monographs with previous projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays also include unique archive material originally published in other languages, made available for the first time in English, opening up historical studies previously little known outside the north European countries. Together with other branches of her work; considering textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists – like the "Linnaean network" – from a Global history perspective.

For regular updates, and to make full use of iTEXTILIS' possibilities, we recommend fellowship by subscribing to our monthly newsletter iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

It is free to use the information/knowledge in The IK Workshop Society so long as you follow a few rules.

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE