ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

KAITAG

Textile Art from Daghestan

In April 1994, I had the pleasure to work as curator for this unique collection of embroidery from the Kaitag people in Daghestan exhibited at Christinehof Manor House in Skåne, Sweden. The unusual patterns embossed with beautiful colour combinations fascinated more than 5,000 textile-interested visitors. The thirty-five embroideries, dated between the 16th and 19th centuries, were on display in five of the castle's newly restored rooms.

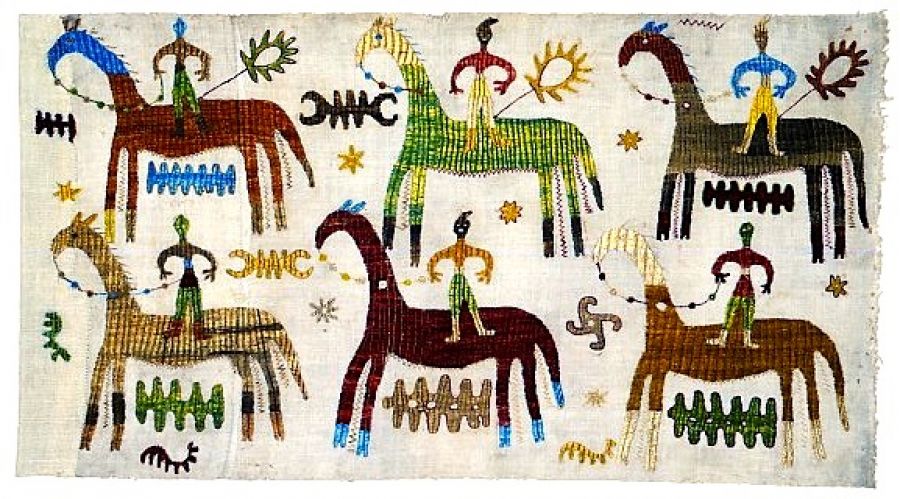

South Dargin region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Horses in two Rows”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 93 x 56 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.

South Dargin region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Horses in two Rows”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 93 x 56 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.We have learnt a lot about the earlier, fairly unknown embroideries from Robert Chenciner, an English researcher on the Kaitag’s regional history and ethnography, as well as everything linked to the embroideries. The results of his six years of fieldwork were presented during the autumn of 1993 in the book Kaitag Textile Art from Daghestan.

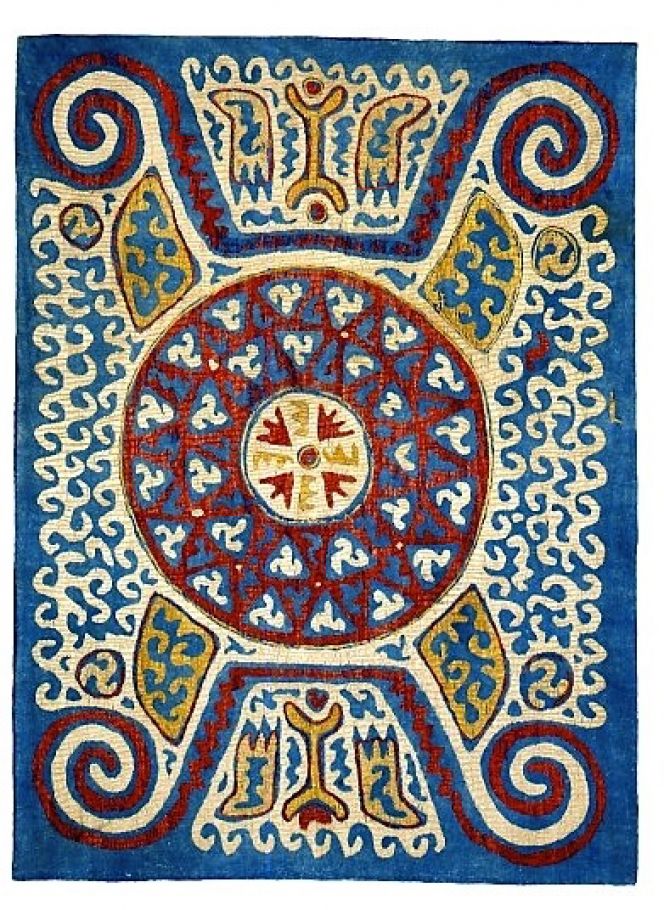

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century. “Spiralling Horns”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 90 x 67 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century. “Spiralling Horns”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 90 x 67 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.The Kaitag region has, over the millennia, been invaded by countless cultures, something which can clearly be seen in the shifting characteristics of the patterns. Here we see, among others; Mongolian, Chinese, Byzantine, Ottoman and Celtic art mixed with the region's art forms. The silk embroideries were used through ritual means, at births, weddings and funerals. Infant cot covers were embroidered with symbols which would protect the newborn from ‘the evil eye’ and before the wedding it was tradition for the bride to be draped in her costly dowry, consisting of a beautifully embroidered cloth. The embroidery was done with great precision and vivid colours, however it was not something which could be admired, as the embroidery’s backside was only meant to be shown. The only situation when the motifs were visible, was when used as ‘grief cushions.’ At funerals the embroideries could be placed over the dead’s face, so that nobody could see the deceased. The hope was that it would rewake the dead to the living.

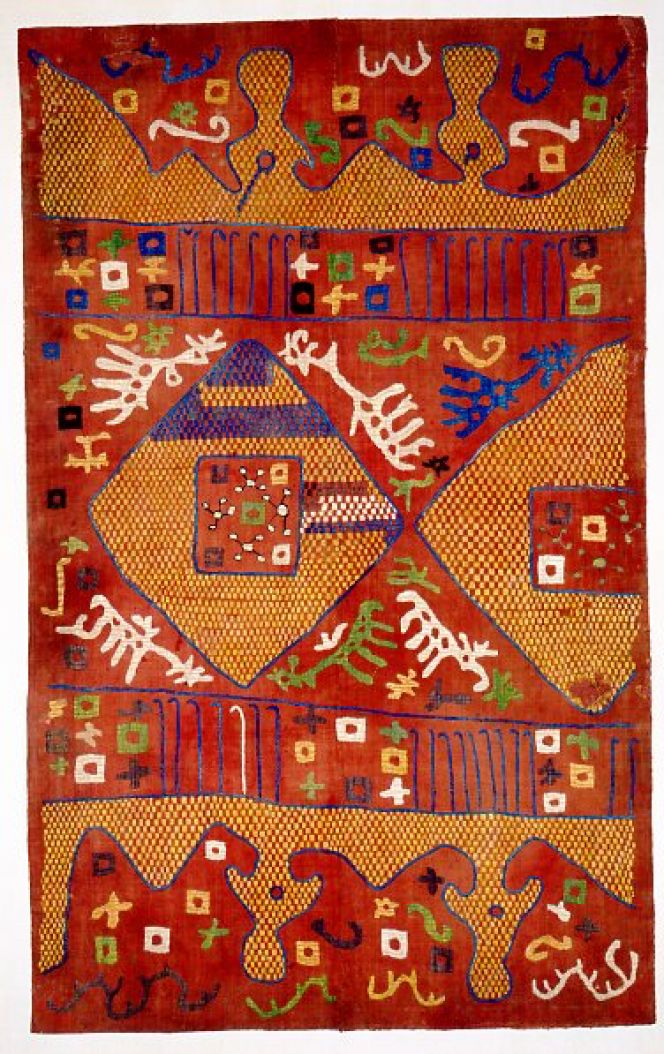

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Elk on Red”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 120 x 78 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Elk on Red”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 120 x 78 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.The embroideries are colourful and at a closer inspection; eleven yellow, three red, two blue, four brown and four green shades added with black can be identified. Different local plants were used for the yellow colouring, like for example weld Reseda luteola. For the red, madder Rubia tinctorum, a plant which flourished in the Kaitag area and for other red colourings the cochineal insects, which were probably imported from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. Indigo Indigofera tinctoria; from Persia or India was a fundamental part of the natural dyes.

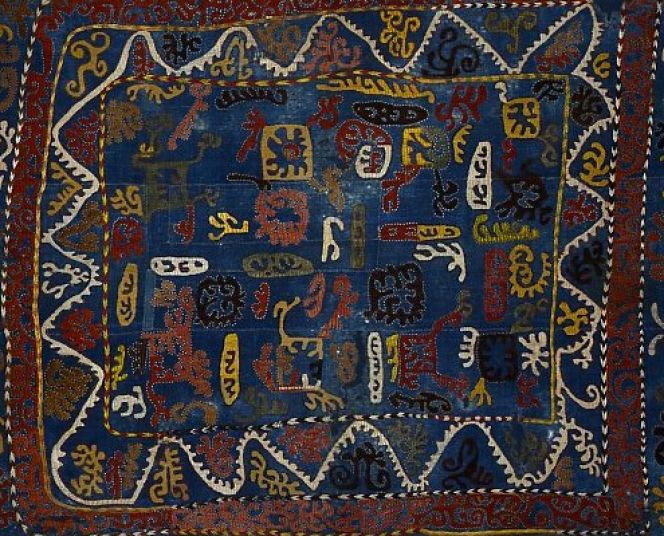

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Hundred Creatures”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 159 x 117 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.

Kaitag region, Daghestan. 18th century or earlier. “Hundred Creatures”. Silk embroidery on cotton, 159 x 117 cm. Courtesy of: Textile Art Publications (TAP), London.The embroidery yarn is comprised of silk, which has been twined by the embroideress. There would have been a high concentration of mulberry trees in Daghestan at the time and so, a large-scale production of silk. The stitches are many but the dominant form is laid and couched stitches. This form of embroidery fills the space in question and gives maximal colour exposition with the use of a minimal amount of yarn. Other stitches which are conveyed are amongst others; running stitch, stem stitch, double chain stitch, cross stitch, herringbone stitch and feather stitch. The background fabric for the vividly coloured embroideries, for the most part handwoven cotton was used and on many occasions three or four smaller pieces were sewn together to form the required size. However some of the embroideries have been sewn on thin silk fabric.

The exhibition took place between 1 April-1 May 1994. It was a cooperation between the senior associate member of Sankt Anthony’s College, Oxford and author Robert Chenciner, Textile Art Publications (TAP) London and The IK Foundation & Company, who arranged the exhibition at Christinehof Castle, Sweden.

Sources:

- Chenciner, Robert, Kaitag – Textile Art from Daghestan, London 1993, Textile Art Publications.

- Hansen, Viveka,‘Kaitag – Textilkonst från Daghestan’, Hemslöjden No: 6, p. 30. 1994.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE