ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

KNOTTED PILE WEAVES 1600 TO 1850

– a Study of Swedish Traditions with Influences from other Geographical Areas

The earliest Nordic pile woven fabric can be traced to archaeological Bronze Age finds about 3500 years old, but from the early modern period, piled weaves were made from yarn or pieces of cloth knotted into a coarse warp and weft of linen or hemp. These textiles were used for warm, comfortable bedcovers, and the oldest surviving rya dates from the 17th century. Though written sources indicate an even earlier history, with regulations for 15th century Swedish nunneries mentioning that ryio formed part of the nuns’ bedclothes. This essay will look closer at the variation of traditional designs in part- or fully-piled techniques – at times including embroidery – which the weavers developed in their domestic sphere by using various qualities of wool, linen and hemp in natural dyed colours or un-dyed yarns. Some bedcovers or seat cushions were for daily use, whilst other such textiles foremost had decorative functions during festive occasions.

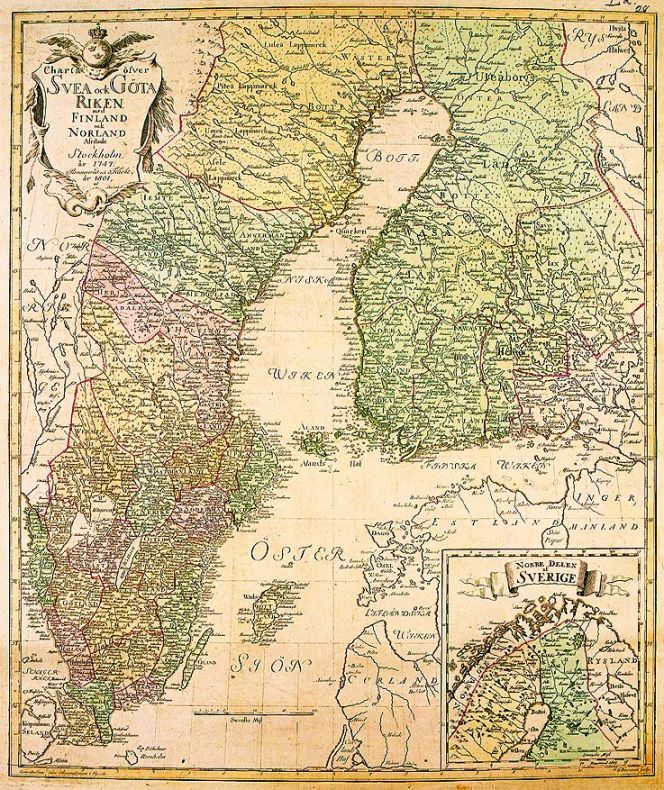

‘A map of Sweden and Finland in 1747’ which gives a good overview of all provinces, where in most areas, some type of pile weaves were produced over the 250-year period. | Åkerland, E. & Biurman, Georg. Published: 1801. (Courtesy of: Helsinki University Library, Wikimedia Commons).

‘A map of Sweden and Finland in 1747’ which gives a good overview of all provinces, where in most areas, some type of pile weaves were produced over the 250-year period. | Åkerland, E. & Biurman, Georg. Published: 1801. (Courtesy of: Helsinki University Library, Wikimedia Commons). Piled weavings, known as flossa or rya, were commonly used in large parts of Sweden for seat cushions and bedcovers, woven in the traditional low loom. Fully piled weaves are a technique often used in Finland, where it is known as ryijy, and in Sweden, it is called rya. The former have been thoroughly researched by U.T. Sirelius and the latter by Vivi Sylwan already in the 1920s respective 1930s. The designs used in the two countries are very similar, and in many cases, it is almost impossible to distinguish between them. The reason for these pile weaves similarities – dating from the 17th to mid-19th century – was probably due to the close contact between the two countries, with most areas of Finland since the Medieval period and up to the year 1809 being part of Sweden. On the island, Åland, situated in the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Finland, bedcovers made in this technique were, for instance particularly well represented even up to the 1860s – judging by dates included on such bedcovers – registered in 42 photographs (kept at the Nordic Museum) taken in 1924 by Miss Lundström in Mariehamn on Åland.

The pile, which tends to be quite thick due to its warming, aims as a bedcover; even so, it seems to have had some regional differences. For instance, according to research by Vivi Sylwan, on the examples from the island of Öland and province of Värmland, the pile is short and cut, whilst in other provinces of Sweden like Uppland where the pile is longer and shaggier, and in Småland the wool for the pile is heavily twisted and the top is uncut, leaving loops.

Firstly, the loom was set up with warp threads in place, then a number of shuttled weft threads were inserted to form a base, and then the knotting would commence. A piece of coloured wool was wrapped and tied around the first pair of warp threads, this process continuing horizontally across the loom breadth, to create a row of knots on the surface. Between each row of knots at least two weft threads were inserted with the shuttle. After a length of the fabric had been woven, the looped surface – depending on the fineness of used materials – was either cut to form a velvet-like surface or left as loops on coarser qualities. Variations, therefore, occur both in the strength of the foundation of piled weavings and the treatment of the surface – giving piled weaves a multitude of designs from plain to richly patterned, partly piled or added with embroidered details.

‘In the chest chamber’ by the artist Jakob Kulle from 1875, demonstrates how art woven textiles inherited through generations were kept safe in a wooden decorated chest. This due to the long-lived tradition to include a multitude of woven and embroidered textiles in the young bride’s dowry in the well-to-do farming communities. Particular in the southern districts of the province Skåne. It seems like the girl wearing a brown fashionable dress is looking at the old treasures, explained by the traditionally dressed young woman. Judging by the design of the cushion cover with star motifs displayed on the chair, it looks to have been woven in the partly-piled “halvflossa”, a popular technique in this area up to about 30-40 years prior to this artwork. (Owner: Malmö Museum. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

‘In the chest chamber’ by the artist Jakob Kulle from 1875, demonstrates how art woven textiles inherited through generations were kept safe in a wooden decorated chest. This due to the long-lived tradition to include a multitude of woven and embroidered textiles in the young bride’s dowry in the well-to-do farming communities. Particular in the southern districts of the province Skåne. It seems like the girl wearing a brown fashionable dress is looking at the old treasures, explained by the traditionally dressed young woman. Judging by the design of the cushion cover with star motifs displayed on the chair, it looks to have been woven in the partly-piled “halvflossa”, a popular technique in this area up to about 30-40 years prior to this artwork. (Owner: Malmö Museum. Photo: The IK Foundation, London). To compare with this well-preserved seat cushion dated to the 1790s, in a star shaped design with zigzag border, in the partly-piled technique or so-called “halvflossa”. It was woven in Skåne – probably in the southwestern part of this province, Sweden. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0029025A).

To compare with this well-preserved seat cushion dated to the 1790s, in a star shaped design with zigzag border, in the partly-piled technique or so-called “halvflossa”. It was woven in Skåne – probably in the southwestern part of this province, Sweden. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0029025A). The so-called part-piled weaves known as halvflossa (or trensaflossa) were produced in several areas, but judging by preserved textiles, the technique seems to have been most popular in a restricted area of the province Skåne, like the cushion depicted above. The coarse linen warp is entirely covered with a single-coloured woollen weft, creating a weft-faced plain weave. The pattern is created by tying woollen knots to the warp in selected areas and designing patterned piled areas in contrast to the flat surface. This type of weaving is quite often accompanied by later added woollen embroidery in stem stitches. The pattern choices for the piled sections include the traditionally used motifs, which are also common in other types of local art weaving and embroidery. Predominately, palmettes, heart rosettes, lily-crosses, double rosettes, eight-pointed stars, zigzag lines and rosettes in diagonal squares.

A fully piled weave which was finer and denser in quality than “rya” was named “flossa”. This unique seat cushion – on linen warp with an unbleached hemp weft ground and woollen knots – of a lion resting on a flower scattered meadow is clearly different in style from the geometrical motifs woven in farming communities. It is believed that the clergy Johannes Norlin’s wife Ulrika Oxelgren, who lived in the Swedish province of Småland (Östra district, Skirö parish), made this and other art woven textiles inspired by nature and biblical stories alike around 1755 to 1775. Furthermore, printed books with ornamental ideas for weaving and embroidery most likely also assisted her when choosing designs. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0327829).

A fully piled weave which was finer and denser in quality than “rya” was named “flossa”. This unique seat cushion – on linen warp with an unbleached hemp weft ground and woollen knots – of a lion resting on a flower scattered meadow is clearly different in style from the geometrical motifs woven in farming communities. It is believed that the clergy Johannes Norlin’s wife Ulrika Oxelgren, who lived in the Swedish province of Småland (Östra district, Skirö parish), made this and other art woven textiles inspired by nature and biblical stories alike around 1755 to 1775. Furthermore, printed books with ornamental ideas for weaving and embroidery most likely also assisted her when choosing designs. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0327829).Inspiration did not originate only from pattern books, nature or geometrical pattern combinations, which had been commonly used in the Nordic area since the Renaissance. Baroque-style flower compositions, etc, became immensely popular during the late 17th and early 18th century. According to in-depth research by the late textile historian Anna-Maja Nylén, the reason was the immensely popular pattern-woven velvets, which were imported from Holland and England. These motif compositions came to a great extent to be used for furnishing textiles by the well-to-do strata of society and, among other matters, gave rise to pile woven decorative rya in clergy communities. Patterns like flowers in urns, flower bouquets, creepers of leaves and matching borders became favoured – several such bedcovers have been preserved with dates from circa 1740 to 1780.

Fully-piled “rya”, woven and used for a warming bedcover in the province of Bohuslän, Inland Torpe district. This detail gives a close-up view of the technique, illustrating that in this area the woollen knots formed an uncut loop piled surface and its colourful geometrical motifs were exactly positioned on the white ground. The bedcover, finished off with a wide border of geometrical star designs was woven in a half-width in a traditional narrow handloom, which made it necessary for the weaver to make two almost identical woven pieces and after the weaving these were stitched together to make a full-sized bedcover. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0095884, detail).

Fully-piled “rya”, woven and used for a warming bedcover in the province of Bohuslän, Inland Torpe district. This detail gives a close-up view of the technique, illustrating that in this area the woollen knots formed an uncut loop piled surface and its colourful geometrical motifs were exactly positioned on the white ground. The bedcover, finished off with a wide border of geometrical star designs was woven in a half-width in a traditional narrow handloom, which made it necessary for the weaver to make two almost identical woven pieces and after the weaving these were stitched together to make a full-sized bedcover. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0095884, detail).![A close-up detail of a partly piled weave, where the surrounding greenish lattice-work was the only piled knots, together with geometrical star motifs in a voided pile weave border (not depicted). Whilst, the colourful finely shaped woollen embroidery represents the focal point on this carriage seat cushion, marked with ‘ANO 1835’ and the initials ‘ECD’ ‘OAS’ – woven and embroidered by the same woman who had both craft skills or by two separate women in Wemmenhög district, Skåne province in southernmost Sweden. Even if not evident, it appears to have been made for a young bride’s dowry, due to the initials of one female name (ending on D = dotter [daughter]) and one male name (ending on S = son [son]). (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0018439, detail).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/6-nm-0018439-800x565.jpg) A close-up detail of a partly piled weave, where the surrounding greenish lattice-work was the only piled knots, together with geometrical star motifs in a voided pile weave border (not depicted). Whilst, the colourful finely shaped woollen embroidery represents the focal point on this carriage seat cushion, marked with ‘ANO 1835’ and the initials ‘ECD’ ‘OAS’ – woven and embroidered by the same woman who had both craft skills or by two separate women in Wemmenhög district, Skåne province in southernmost Sweden. Even if not evident, it appears to have been made for a young bride’s dowry, due to the initials of one female name (ending on D = dotter [daughter]) and one male name (ending on S = son [son]). (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0018439, detail).

A close-up detail of a partly piled weave, where the surrounding greenish lattice-work was the only piled knots, together with geometrical star motifs in a voided pile weave border (not depicted). Whilst, the colourful finely shaped woollen embroidery represents the focal point on this carriage seat cushion, marked with ‘ANO 1835’ and the initials ‘ECD’ ‘OAS’ – woven and embroidered by the same woman who had both craft skills or by two separate women in Wemmenhög district, Skåne province in southernmost Sweden. Even if not evident, it appears to have been made for a young bride’s dowry, due to the initials of one female name (ending on D = dotter [daughter]) and one male name (ending on S = son [son]). (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, NM.0018439, detail). Even earlier in the 15th and 16th centuries, “Oriental” pile-woven carpets had some influence over similar techniques and patterns used in European textile furnishing. Overall, it must be stated that the rya weaving and similar style pile woven textiles, including knots, have been globally used due to their widespread practical advantages for carpets, bedcovers, seat cushions, religious objects and warm clothes in geographical areas like Spain, the Nordic countries, Turkey, Egypt, Peru, Central Asia, Iran, Caucasus, Central Africa, Japan and Northern China.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art, London 1996 (pp. 80-89).

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969 (pp. 172-186).

- Sirelius, U.T., The Ryijy-Rugs of Finland, Helsinki 1926.

- Sylwan, Vivi, Svenska ryor, Stockholm 1934.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden (Four images and information from catalogue cards. DigitaltMuseum/Creative Commons & Information about photographs by Miss Lundström in 1924: search words ‘rya Finland’).

- Walterstorff, Emelie von, Textilt Bildverk, Stockholm 1925 (pp. 24-34 & Plates 39-56).

- Wistrand, P. G. ‘Anteckningar af en småländsk prestfru, förda under åren 1751-1810’, Fataburen 1911, pp. 65-100.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE