ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

LAUNDRY OCCUPATIONS

– A Case Study via Censuses in Whitby 1841 to 1911

Easy access to water was vital, and here the Whitby area had a definite advantage with the River Esk. It is clear from the censuses that between 1841 and 1911, many local laundresses lived near the river. As an alternative, rainwater could be collected in barrels, and this was considered to give the softest wash. The garment being washed would be beaten clean or worked over with a dolly or washing bat. Wooden tubs of various sizes would also be used for soaking in an alkaline liquid, usually lye, which was fine white ash from the hearth. However, during the 19th century, white ash began to be scarce, and various kinds of soap were widely introduced to remove stains. Soap had been available long before this time, but it was expensive for most people. This essay will look closer into the hundreds of registered laundresses and washerwomen who worked locally according to the censuses from 1841 to 1911.

This early 19th century depiction of Bagdale Road in Whitby somewhat predate the first census of 1841, but even so being a good comparison. The people in clothes typical of the time include a woman carrying a laundry basket on her head. She is probably a laundress on her way either to collect dirty washing, or to return newly washed and ironed clothes to their owner at one of the large houses in the district. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection).

This early 19th century depiction of Bagdale Road in Whitby somewhat predate the first census of 1841, but even so being a good comparison. The people in clothes typical of the time include a woman carrying a laundry basket on her head. She is probably a laundress on her way either to collect dirty washing, or to return newly washed and ironed clothes to their owner at one of the large houses in the district. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection).The 1841 census lists only ten women under the occupation ‘Laundresse’, contrasting with the censuses of later decades, which would record from five to ten times as many. The reason for the change was probably the developing form of the census. Many more than ten women were active as laundresses in Whitby in 1841, though if they were not paid employees or ran a business of their own, they would not have been listed as laundresses. The ten women listed were thus very probably either paid employees in a large household that needed more or less permanent access to laundry service or self-employed. Nine of these ten laundresses of 1841 were between 45 and 60 years old; it was an occupation that attracted middle-aged and elderly women with no small children to look after since the working day would have been long. The many others working in this field – invisible in the 1841 census – would have either worked independently washing clothes for their neighbours or for other Whitby residents who desired and at the same time could afford to employ somebody to perform these duties on a fairly regular basis.

But in 1851, no less than seventy women declared themselves a ‘Laundresse’, four a ‘Laundresse, retired’ and 28 a ‘Washerwoman’. These two terms seem merely to have been different ways of describing the same occupation. The middle-aged or elderly unmarried women and widows were now supplemented by a group of younger unmarried women still living with their parents and thus able to contribute to the family finances. Four elderly women – between 66 and 76 years old – were described as retired, proof that laundering was exhausting and difficult for those of advanced years. No other female textile occupations were qualified by the word ‘Retired’ in the census. Most of these washerwomen lived in the oldest and most crowded part of the town. There were also four women in their fifties employed as ‘Mangle Women’, whose job would have been to complete the work of the washerwomen by ensuring a smooth, even finish for clothes, sheets and other household linen after washing. One woman in Church Street was described as owning a ‘Mangle’. Of the total of 109 women active in this field, only 28 were under forty years old, with the majority between 45 and 65 and the oldest 75.

By the time of the 1861 census, the number of laundresses had diminished somewhat, but there were still many of them in Whitby. 55 women gave their occupation as ‘Laundresse’, four as ‘Laundresse, retired’ and 20 as ‘Washerwoman’. Among these, in Henrietta Street, were three generations of a family all working as laundresses: Elizabeth (44) and Elinore (23) Corne, with grandmother Emma Storey who, as a widow of 80, was the oldest to be active in this occupation. Two sisters worked as ‘Laundry Maids’, a category not found in the two earlier censuses, implying that they sorted and folded laundry and in general helped with the mangling. There was also one woman who gave her occupation as ‘Mangling’ and two ‘Mangle Keepers’. Presumably, one could either leave laundry with them for mangling or call round and do the mangling oneself for a fee. This census contained more younger women than before, with 29 out of 82 below the age of forty.

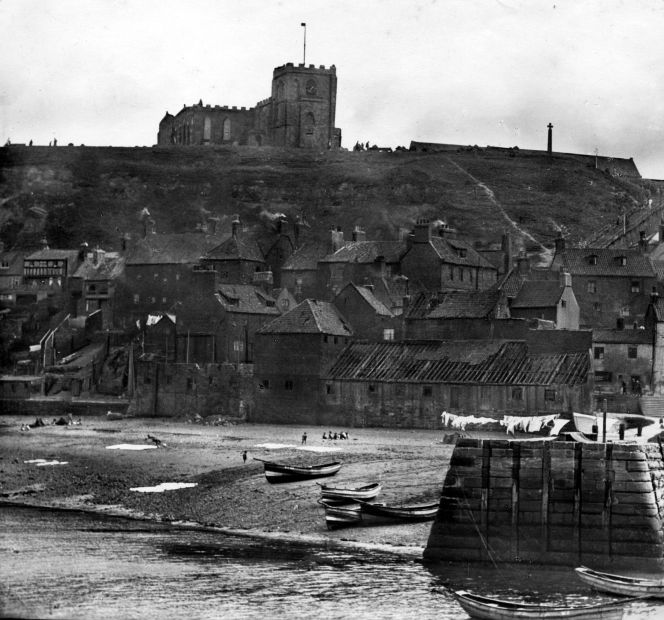

‘Entering the harbour at Whitby’ in 1872. Just like on several other contemporary local paintings and photographs taken a few decades later – washing lines with linen laundry are visible along the River Esk. |Watercolour by Edwin Cockburn (1814-1873). (Private Collection).

‘Entering the harbour at Whitby’ in 1872. Just like on several other contemporary local paintings and photographs taken a few decades later – washing lines with linen laundry are visible along the River Esk. |Watercolour by Edwin Cockburn (1814-1873). (Private Collection).By the 1871 census, the number had sunk still further, with 44 ‘Laundresses’, two ‘Laundresse, retired’ and 13 ‘Washerwomen’. Perhaps this reduction of the total by 20 was caused by those who washed for the middle classes now being classified as ‘House Work, Servant’, an ever more common category. The importance of access to running water can be seen clearly in the fact that nine laundresses were living near the River Esk, in Mayfield Place, Ruswarp Village and Esk Cottages. This year, no ‘Laundry Maids’ were listed, but there was one ‘Laundry Man’, a 68-year-old working with his wife of the same age who was ‘Laundresse’ at Sneaton Castle. Just as ten years earlier, one woman was registered as ‘Mangling’ and two as ‘Mangle Keepers’. The idea that women could pay for mangling their own laundry is probably reinforced by the description ‘keeps public mangle’. 18 of the 62 women and one man were under forty years old, while the oldest working woman was 76.

Washing lines extended along the River Esk. One of several photographs taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe including laundry during the 1880s and 1890s (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 6-55B).

Washing lines extended along the River Esk. One of several photographs taken by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe including laundry during the 1880s and 1890s (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 6-55B).The 1881 census again lists fewer laundresses than ten years before, with 45 ‘Laundresses’, two ‘Laundresse retired’, and only three ‘Washerwomen’ plus one ‘Washerwoman, retired’. The population as a whole had somewhat increased, and just as in 1871, one can assume that domestic workers had a lot of washing to do among their duties, but was simply described as ‘House Work, Servant’. In 1861 and 1871, several women had been working as laundresses in the area of Mayfield Cottages, Ruswarp village and Ruswarp cottage; now, in 1881, ten women were described as laundresses at these addresses near running water. Church Street and its many adjacent yards were not only rich in laundresses because the area was so heavily populated, but also because it was near the mouth of the River Esk. It is also interesting to note the presence of laundresses at Boulby Bank – laundresses would also be found there 10, 20 or 30 years later – and this can be compared with the many photographs from the time showing laundry hung out to dry (see image below). The specialist mangling work and public mangle mentioned in earlier censuses no longer appear this year, probably because handy small mangles were now more common, convenient for servants to use and for neighbours to borrow and lend among themselves. The 1881 census shows much the same distribution of ages as ten years before, with 15 laundresses out of 51 under forty years of age and the oldest 74.

This second photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe showing a woman hanging up washing at Boulby Bank in Whitby, an area where many laundresses lived and worked according to repeated censuses. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-48).

This second photograph by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe showing a woman hanging up washing at Boulby Bank in Whitby, an area where many laundresses lived and worked according to repeated censuses. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe 13-48).The 1891 census lists rather more laundry workers than ten years earlier, with 52 ‘Laundresses’, one Laundresse Assistant’, one ‘Laundry Man’ and two ‘Laundry Women’. This year, only two women described themselves as a ‘Washerwoman’ while there was also a specialist ‘Linnen Washerwoman’. The slight increase in numbers is virtually negligible, and just like ten and twenty years before it can be assumed that those described as ‘House Work Servant’ included laundry work with their other duties. Mayfield Cottages was still a place where five ‘Laundresses’ found it convenient to live. The first-ever recorded ‘Laundresse Assistant’ was a 14-year-old girl at High Stakesby who worked together with her 22-year-old ‘Laundresse’ sister. Just as ten years earlier, no one is described in this census as a ‘Manglewoman’. The one ‘Laundry Man’ was 54-year-old William Waller Richards who worked with his wife, ‘Laundress’ Mary Ann Richards, 53, at Rose Cottage. There was little change in age distribution, with 15 of the 59 women under 40 and the oldest 76.

Washing laid out for drying and bleaching by the sea, which must have been a common occurrence in summer since several photographs have survived of various places along the Whitby shore with large quantities of linen laid out on the sand. Together with washing lines stretching along the beach, taken by an unknown photographer around 1890 to 1900. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photograph book 3/20).

Washing laid out for drying and bleaching by the sea, which must have been a common occurrence in summer since several photographs have survived of various places along the Whitby shore with large quantities of linen laid out on the sand. Together with washing lines stretching along the beach, taken by an unknown photographer around 1890 to 1900. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photograph book 3/20).

The 1901 census shows an increase in numbers compared to ten years before, with 64 recorded as ‘Laundresse’ and one as ‘Laundresse retired’. Many factors may have contributed to this increase. First and foremost, each customer would now have possessed more clothes, especially a greater number of light-coloured garments needing more frequent washing. Also, the general rise in the standard of living around the turn of the century, plus the growth of tourism, may have provided more work for laundresses. Also, more work categories were now defined in the census, including ironing, assistants, hand washers, hand ironers, laundry maids, laundry hands, etc. One woman described herself as working with Dry Cleaning and one man as a Garment Dryer and Cleaner. Increasing mechanisation make it likely that fewer laundresses and other personnel were now required to do the same amount of work as before. Otherwise, women of all ages still predominated in the world of laundry work, with sisters, mothers and daughters, and neighbours working together, and in a few cases married couples. As always, many unmarried women worked in this line of business: 38 of the 62 were unmarried while three were widows. So it was still the case that unmarried young women living at home might help to support their family just as laundry work could help unmarried middle-aged or elderly women earn a living.

Once again, in 1911, Church Street and its neighbouring yards and alleys was where most people involved with laundry work lived: 38 of the 62 were registered at addresses here. Most of the rest also lived in the cramped living conditions of the most crowded parts of Whitby. In 1911, washing linen was still heavy work that caused great strain to the body, even if some workers could now benefit from such innovations as simple washing machines driven by electricity or steam. A novelty in this census was that there were now no laundresses over 70 years old. The universal old age pension had been introduced in 1908, allowing less well-off women for the first time to take advantage of their age and give up such demanding work but still receive a small income.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 299-303).

- The National Archive (Census 1911, Whitby. Digital source).

- The Public Catalogue Foundation, Oil Paintings in Public Ownership in North Yorkshire, London 2006.

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive. Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Photograph books).

- Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection. Whitby Lit. & Phil. (Studies of a wide selection of local photographs and prints).

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library (Census 1881-1901 microfilm).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE