ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

LINEN TABLECLOTHS AND NAPKINS

– at a Manor House in 1758

To have a meal on white linen cloth had Medieval traditions in wealthy Swedish homes and became an even more important part of festive dinner arrangements over the coming centuries. Gradually, napkins were introduced in the 16th century to protect the long tablecloths and encourage more refined table manners. These two linen categories were often acquired in matching sets with near-identical patterning. The fashion to own such desirable imported or domestically manufactured woven linen with tablecloths and napkins of the same weaving technique has been revealed via listed items in an Inventory dating 1758 at Christinehof Manor House in southernmost Sweden. This detailed handwritten document will be compared with contemporary artwork, a museum display, preserved table linen, and the aristocratic Piper family’s shares of two linen manufacturers.

This undated 18th century painting of a ‘Washerwoman’ by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), gives a glimpse into how linen was put to soak in a wooden barrel. Probably it is winter or a damp day as linen is hanged to dry indoors. Washing linen may include all from the smallest cap to the largest tablecloth and it must be emphasised that such cloths become very heavy; which would lead to strenuous work for hired washerwomen or some indoor servants employed to do the laundering at regular basis at a manor house like Christinehof. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 780. Wikimedia Commons).

This undated 18th century painting of a ‘Washerwoman’ by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), gives a glimpse into how linen was put to soak in a wooden barrel. Probably it is winter or a damp day as linen is hanged to dry indoors. Washing linen may include all from the smallest cap to the largest tablecloth and it must be emphasised that such cloths become very heavy; which would lead to strenuous work for hired washerwomen or some indoor servants employed to do the laundering at regular basis at a manor house like Christinehof. (Courtesy of: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM 780. Wikimedia Commons).The geographical origin of the table linen is only stated in the handwritten 1758 document for a small number of items, like; ‘2 tablecloths, 3 dozen napkins from Pomerania, marked with C 58’. However, the most probable weavers for most of such linen was the domestic Flor Linen Manufacturer in Helsingland province, which produced luxury goods such as damask as well as other sorts of linen qualities, where the Piper family owned ’45 shares’. According to the late textile historian Ernst Fischer’s research in the 1950s, who described linen in storage on the Piper manor houses in the province of Skåne – one napkin only has been preserved woven prior to 1758. Interestingly, he noted: ‘On Sövdeborg is thus a napkin with a rich border, the initials C P [Christina Piper, 1673-1752] in corner monograms and the Piper coat of arms in the mirror. This napkin originates in the early 18th century and demonstrates a quality which indicates that one would like to assign it to the Flor Linen Manufacturer in Helsingland, which was founded around this time [in 1729]’. Furthermore, in 1753, another Swedish linen manufacturer started a production in the town of Vadstena. Tablecloths of linen were produced from the start, but damask weaving was first introduced after this 1758 Inventory was written – in the 1770s. It was highly likely, however, that some other linen qualities had their origin there, due to that the Piper family in 1755 invested in ‘The Share number 55 in Vadstena Fine Linen Manufacturer’.

This well-preserved linen damask napkin, marked/dated 1757 and ‘SCL 15’ in cross-stitch is likely to have been very similar to some of the napkins listed in the Inventory at Christinehof. The cloth may be comparable from several angles, most obvious the dates with just one year apart and the advanced damask technique. But also according to facts amassed by the present-day owner, which reveals that the napkin was woven by the Flor Linen Manufacturer in Helsingland, where the Piper Family was frequent customers. Additionally the napkin had originally been in the ownership of Sara Catharina Linroth (1739-1826) who married baron Carl Gustaf Löwenhjelm (1732-1788) in the year 1757, who belonged to another noble family in Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museums, Sweden. MMT 000419).

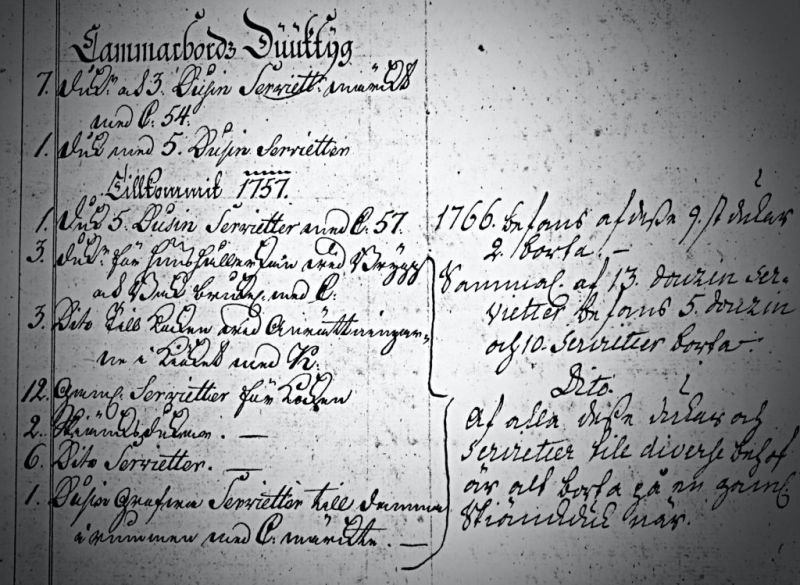

This well-preserved linen damask napkin, marked/dated 1757 and ‘SCL 15’ in cross-stitch is likely to have been very similar to some of the napkins listed in the Inventory at Christinehof. The cloth may be comparable from several angles, most obvious the dates with just one year apart and the advanced damask technique. But also according to facts amassed by the present-day owner, which reveals that the napkin was woven by the Flor Linen Manufacturer in Helsingland, where the Piper Family was frequent customers. Additionally the napkin had originally been in the ownership of Sara Catharina Linroth (1739-1826) who married baron Carl Gustaf Löwenhjelm (1732-1788) in the year 1757, who belonged to another noble family in Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museums, Sweden. MMT 000419). This is a section of page 48 from the “Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758”. The additional notes eight years later also reveal that several of the listed linen, which had been in frequent use in the kitchen, for dusting rooms etc were by now in 1766 missing – probably due to being worn-out. See the listed table linen from this text section in an English translation below. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof… D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

This is a section of page 48 from the “Inventory of Furniture and All Sorts of Household Utensils at Christinehof Manor House Anno 1758”. The additional notes eight years later also reveal that several of the listed linen, which had been in frequent use in the kitchen, for dusting rooms etc were by now in 1766 missing – probably due to being worn-out. See the listed table linen from this text section in an English translation below. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof… D/Ia). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Chamber [Table] Tablecloths

7 Tablecloths with 3 dozen Napkins marked with C54.

1 Tablecloth with 5 dozen napkins.

Added in 1757

1 Tablecloth, 5 dozen napkins with C57.

In 1766, of these 9 tablecloths, 2 are missing.

3 Tablecloths for the housekeeper, to be used for brewing and baking, with C.

3 Ditto for the cook, used for preparations in the kitchen, with K.

12 old napkins for the cook.

2 Buffet tablecloths.

6 Ditto napkins.

1 Dozen coarse napkins, for dusting in the rooms, marked with C.

[1766] In total of 13 dozen napkins, 5 dozen and 10 single napkins are missing.

Ditto. Of all the tablecloths and napkins for various uses, all are missing besides an old star [patterned] tablecloth.

……...........................................

The 1758 inventory listed a total of 41 linen tablecloths of various qualities, together with 539 napkins, all in the care of the housekeeper ‘Madam Nordenmarck’. The most complex design was described as ‘His Excellency’s Arms woven into…’ in ‘Damask diaper with 24 napkins’. Furthermore, ‘3 tablecloths and 18 napkins’ were registered using the same weaving technique. It may also be noted that the majority of the linen fabrics were marked with ‘C’ and the years ’54’, ’57’ or ’58’ [in the 1750s] referring to the tenant in tail, who at the time was Carl Fredrik Piper (1700-1770). Listed patterns in the Inventory included ‘Night and Day motif ’, ‘The French rose’ and ‘Fortification pattern’ – all woven in variations of diaper or damask with geometric patterning and a wide border with contrasting designs. The substantial number of listed napkins (539) appears to be evidence of frequent and sizeable dinner parties. Napkins measured circa 80-90 cm in square shape, that is to say, larger than models of today. The most preferred fashion in the mid-18th century for folding napkins was the quite simple so-called “hovsnibben”, as may be studied in the reconstruction of the laid table below.

In stark contrast to the everyday life of the illustrated linen washerwoman, this reconstruction of an elegantly laid table in a Swedish home of the nobility in mid-18th century, demonstrates how the linen napkins and large-size tablecloth were important parts of the festive meal. One can reflect on that the extensive width as well as length of the fabric was necessary for the tablecloth to reach the floor at all four sides of the table. However, one may notice that the choice of linen tablecloth for this reconstruction has been woven in full width, which was not customary around 1750. Even if the hand-woven cloth in damask or diaper had been purchased from a well-established linen manufacturer, the loom widths were not wide enough, so two exact pieces of fabric had to be finished off with a long seam to obtain the desired width – traditionally in the finest stitching to be as invisible as possible. (Courtesy of the Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0000533, The Exhibition “Dukade bord”. Digitalt Museum).

In stark contrast to the everyday life of the illustrated linen washerwoman, this reconstruction of an elegantly laid table in a Swedish home of the nobility in mid-18th century, demonstrates how the linen napkins and large-size tablecloth were important parts of the festive meal. One can reflect on that the extensive width as well as length of the fabric was necessary for the tablecloth to reach the floor at all four sides of the table. However, one may notice that the choice of linen tablecloth for this reconstruction has been woven in full width, which was not customary around 1750. Even if the hand-woven cloth in damask or diaper had been purchased from a well-established linen manufacturer, the loom widths were not wide enough, so two exact pieces of fabric had to be finished off with a long seam to obtain the desired width – traditionally in the finest stitching to be as invisible as possible. (Courtesy of the Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NMA.0000533, The Exhibition “Dukade bord”. Digitalt Museum).In such a detailed listed Inventory from the 1750s and with a comparable study of material culture in the form of preserved physical objects, contemporary interior paintings and other primary sources it is clearly visible that the consumer revolution was well-established within the nobility in Sweden at this time. This did not only affect their festive arrangements, but also their everyday life, influenced by manufactured produce and imported goods from all sorts of perspectives. Exquisitely woven table linen in damask or diaper was one such obvious category, which substantiated one’s high standard of living. But simpler linen or ‘old’ pieces not seen as representative at the family table, were also of importance for the household (presented in a complete translation above). Other objects listed in significant quantities, either necessary or desired for festive or everyday meals, included large sets of true porcelain and soft-paste porcelain services, wineglasses, carafes, tureens, fruit baskets, butter boxes, bowls, plates of tin and much more. The highest-valued crystal and porcelain pieces were even decorated with the Piper family’s coat of arms.

This is the twelfth essay based on an Inventory dated 1758 at Christinehof Manor House. Quotes from the original documents are translated from Swedish to English.

Sources:

- Christinehof Manor House, Sweden (research visits from the late 1980s to 2016).

- Fischer, Ernst, Linvävarämbetet i Malmö och det skånska linneväveriet, Malmö 1959 (Quote p. 271).

- Hansen, Viveka, Inventariüm uppå meübler och allehanda hüüsgeråd vid Christinehofs Herregård upprättade åhr 1758, Piperska Handlingar No. 2, London & Whitby 2004 (pp. 32-36 & 38-62).

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, (Piper Family Archive. Inventory 1758: no D/Ia & Shares in linen manufacturers: F/IId 2).

- The Nordic Museum (Nordiska Museet) Stockholm, Sweden. (Reconstruction of how a mid-18th century table was laid, photo from the exhibition “Dukade bord”. DigitaltMuseum).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE