ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

LINEN, WOOL, COTTON AND SILK GARMENTS

– in an 18th Century Farming Community

This essay aims to present a transcription – in an English translation for the very first time – of Pehr Osbeck’s (1723-1805) observations related to clothes for everyday use and festive occasions in a farming community. Some aspects were long-lived traditions, fashionable influences, household economy, and the overall demand for various garments. His learned experiences over time were published in 1796. Osbeck was industrious, and during his almost 50 years in the parish of Hasslöv – besides his priesthood duties – he had time for in-depth reflections concerning botany, zoology and social circumstances in the countryside in the Halland province. The transcription will be supplemented with a short introduction of his life as well as images of preserved garments and artworks originating from the same geographical area in the south of Sweden.

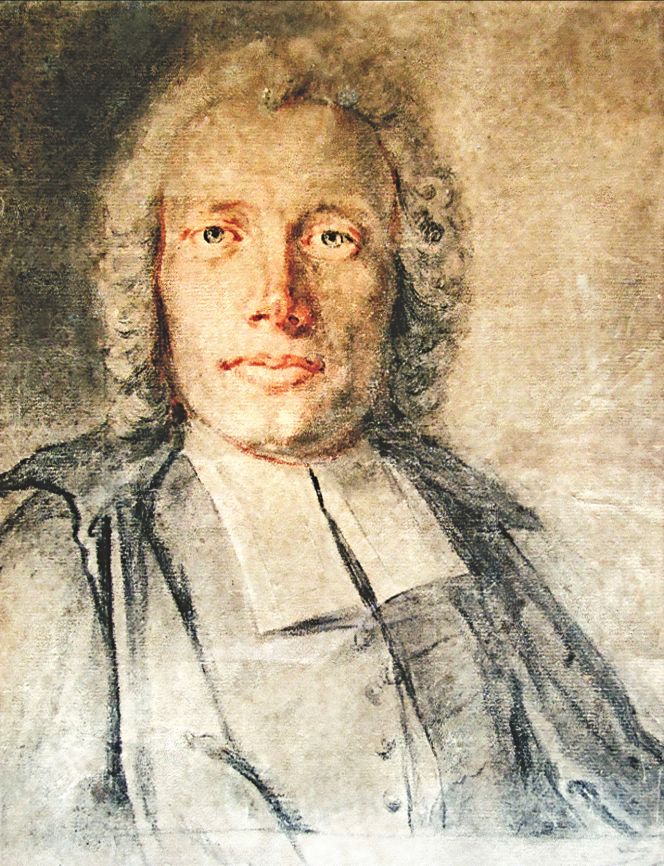

Portrait of Pehr Osbeck painted by the artist Magnus Lindgren, probably during Osbeck’s early years as rector in the parish of Hasslöv. He is portrayed wearing his everyday clerical garb, a long black frock coat, traditionally stretched over the shoulders and buttoned down the front, falling in neat pleats down the back. (The portrait hangs in the church of Hasslöv, Sweden). Photo: Lars Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Portrait of Pehr Osbeck painted by the artist Magnus Lindgren, probably during Osbeck’s early years as rector in the parish of Hasslöv. He is portrayed wearing his everyday clerical garb, a long black frock coat, traditionally stretched over the shoulders and buttoned down the front, falling in neat pleats down the back. (The portrait hangs in the church of Hasslöv, Sweden). Photo: Lars Hansen, The IK Foundation.In his early 20s, Pehr Osbeck became a student at Uppsala University, where he signed in on 20 September 1745. He primarily studied for a priesthood and natural history under Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). After his student years, Osbeck came to work as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist for the Swedish East India Company’s ship Prins Carl to Canton in China from November 1750 to June 1752. During the voyage, the ship was also anchored at Cadiz, Java, and Ascension – a journey financed with his employment as the ship’s chaplain. From 1753 to 1758, he was employed as a house chaplain, botanist and tutor by Count Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770) at Åkerö manor house. According to letters and writings that are still intact, he appears to have found this period to be one of the most harmonious periods in his life. During his stay with the Tessins, Osbeck collected his notes from the long voyage and, in 1757, published his Dagbok öfwer en Ostindisk Resa åren 1750, 1751, 1752 (Diary from an East India Passage in the years 1750, 1751, 1752), which was later published in several foreign languages. Osbeck’s period as a man of science among the elite of society came to an abrupt end in 1758, however, at a time when Tessin no longer had the financial means to keep him in his employ. Osbeck was forced to seek a living within the priesthood, and via Tessin’s contacts, he was assigned to the parish of Hasslöv in the southern part of the Halland province. Here, he gained a new life in many respects, as this came to be the place where the former apostle spent the rest of his life, besides which he married Susanna Dahlberg the same year. Eight or nine children (three died in infancy) were born into the marriage, which meant a heavy burden of responsibility, and they lived in straightened economic circumstances. Osbeck was active until his final years and died in 1805, aged 82.

During his many years in the parish of Hasslöv, Osbeck could hardly avoid seeing the changes in the parishioners’ way of dressing. It was principally their festive garb that interested him, as the everyday clothes presented fewer variations. Not only were the styles changed, but the colours and materials also differed. For the men, the novelty was that in 1758, they mainly wore grey homespun, whereas 40 years later, they dressed in blue adorned with silver buttons and wore hats with velvet ribbons, silk braids, and fur coats. Here exemplified with a well-preserved indigo/woad blue dyed twill-woven woollen coat, in use circa 1750-1800, Höks district in Halland province. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0053549. DigitaltMuseum).

During his many years in the parish of Hasslöv, Osbeck could hardly avoid seeing the changes in the parishioners’ way of dressing. It was principally their festive garb that interested him, as the everyday clothes presented fewer variations. Not only were the styles changed, but the colours and materials also differed. For the men, the novelty was that in 1758, they mainly wore grey homespun, whereas 40 years later, they dressed in blue adorned with silver buttons and wore hats with velvet ribbons, silk braids, and fur coats. Here exemplified with a well-preserved indigo/woad blue dyed twill-woven woollen coat, in use circa 1750-1800, Höks district in Halland province. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0053549. DigitaltMuseum). The women’s clothes varied more between the parishes, but Osbeck could also see fashions become more personalised with individual ideas of how different fabrics were combined to the best effect. They were mainly dressed in linen shirts, skirts made of broadcloth, and woven ribbons, and some wore silk scarves around the neck, sheepskin skirts in winter, red knitted jackets, white linen aprons and blue cotton cloth on the head. This knitted jacket of an 18th century model is an excellent example of the finely developed knitting traditions in the province. Notice the ornamental star motifs within a latticework on the single-coloured jacket. According to the museum catalogue card, this particular garment had been made and initially used around 1750 to 1779, Årstad district, Halland province. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0134914. DigitaltMuseum).

The women’s clothes varied more between the parishes, but Osbeck could also see fashions become more personalised with individual ideas of how different fabrics were combined to the best effect. They were mainly dressed in linen shirts, skirts made of broadcloth, and woven ribbons, and some wore silk scarves around the neck, sheepskin skirts in winter, red knitted jackets, white linen aprons and blue cotton cloth on the head. This knitted jacket of an 18th century model is an excellent example of the finely developed knitting traditions in the province. Notice the ornamental star motifs within a latticework on the single-coloured jacket. According to the museum catalogue card, this particular garment had been made and initially used around 1750 to 1779, Årstad district, Halland province. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0134914. DigitaltMuseum).![Map of Halland province, dated 1807, is almost contemporary to Pehr Osbeck’s published book in the previous decade. The parish of Hasslöv [marked ‘Hasslöf’ on the map] was situated in Höks district, a parish bordering the most southerly province Skåne in Sweden. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Old Map Collection. Alvin-record:55040. Part of the map in the picture. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4a-map-1807-664x821.jpg) Map of Halland province, dated 1807, is almost contemporary to Pehr Osbeck’s published book in the previous decade. The parish of Hasslöv [marked ‘Hasslöf’ on the map] was situated in Höks district, a parish bordering the most southerly province Skåne in Sweden. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Old Map Collection. Alvin-record:55040. Part of the map in the picture. Public Domain).

Map of Halland province, dated 1807, is almost contemporary to Pehr Osbeck’s published book in the previous decade. The parish of Hasslöv [marked ‘Hasslöf’ on the map] was situated in Höks district, a parish bordering the most southerly province Skåne in Sweden. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, Old Map Collection. Alvin-record:55040. Part of the map in the picture. Public Domain).From 1758 until the publication of Pehr Osbeck’s book Utkast til beskrifning öfver Laholms Prosteri (Outlines of a description of the Deanery of Laholm) in the year 1796, he collected material about customs and traditions, plants and general conditions of life in the area. These detailed observations were connected to life in a strictly limited geographical area over almost forty years, including studies of spinning materials, knitting, and weaving. The focus of this essay is notes on how the rural population dressed. Here follows the transcription – in an English translation from the Swedish language – of the text sections, including his reflections about local clothing traditions.

- ‘At my arrival here in 1758, men almost everywhere wore grey woollen wadmal clothes, with grey, brown or blue waistcoats, seldom red – hooks instead of buttons and without pockets. Nowadays [the 1790s], some of them are dressed in blue and, in particular, the farm hands who showed off with silver-plated buttons, fashionable pockets, hats with velvet ribbon, silver buckles, silk cords and tassels, which dangle to and fro as well as a long Spanish cane, if it shall be perfect. The young men could not be without loose cuffs, furs, mittens and a cane. With what shall they warm themselves in old age?

- The women’s costumes are not the same in all parishes. In Wåxtorp parish, they use their linen closeup on the neck, just as the men; formerly, the maids used their hair only; nowadays, mostly caps or head cloth like the [married[ women. Some of them rub their head cloth with glass so it shines. Here, caps are used without ribbons around the head, which otherwise are common in other parishes. The bride [unmarried] maids keep the old tradition going bare-headed with plaited hair. In Hasslöv parish, the [married] women have held the old customs to use a white head-cloth or a cap of black silk fabric, whilst the maids use other colours. Neckcloths of silk increase year by year, almost everywhere, also by the men, but the women often use several silk cloths, two around the neck and one to cover the hymn book, when they go to church. Red skirts and blue sweaters are part of the festive costume. White hairy lambskins or sheepskins skirts (the wool nevertheless cut) added with a hand’s breadth red broadcloth. Scarlet or other red cloths at the skirt hemline are commonly used on everyday clothes, particularly during harvest time. Red knitted sweaters and black woollen wadmal sweaters, some with a sizeable round-shaped silver leaf placed on each side of the chest, are church clothes too; otherwise hairy sheepskin sweaters or knitted sweaters during the winter, but sweaters are not used in the summer.

- They use white aprons, commonly two, one on the outer skirt and one worn under the outer skirt. During rain and poor weather, they pull the skirt over their head and let the wet, long linen undergarment only cover their back. So, they are hardly worried about colds and the consequences that may follow. On the other hand, in some parishes, it is customary to use a blue or multicoloured cotton cloth over the head and tie it under the chin, which means they believe it to be perfectly protected.

- Previously, widows wore wide black coats during mourning, a no longer used custom. The custom of the widow or closest female relatives going to the grave with a black skirt pulled over the head is also no longer used. During the mourning period, the neckcloth is tucked under the black sweater, otherwise draped down the back.

- Almost every parish has its own customs. In Hasslöv parish, most weddings are held over three days, which nevertheless have been few during the last couple of years. The marriage ceremony is partly held in the church and partly in their house.

- The betrothal was formerly in the church, which is still in Hishult parish, where the priest has this ceremony and offers it on the same occasion, but in other places, the priests are not present at the betrothal. The bride is usually dressed by the groom’s closest family member in a foolish[!] way, with a red skirt and black sweater, or if the lack thereof, in another knitted sweater.’

Pehr Hörberg, interestingly, also described the headgear used by the bride: ’Some decoration is hung on the chest, equally as a crown is placed on her brushed-out hair.’ Comparable to this traditional elaborate crown, which was initially used in the same Höks district in Halland province. The striking headgear includes metallic lace, glass pearls, a selection of colourful silk ribbons, and cut fabric pieces to hang down the back of the young woman. | The illustrated crown is undated but probably originating from the second half of the 18th century. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0052127. DigitaltMuseum).

Pehr Hörberg, interestingly, also described the headgear used by the bride: ’Some decoration is hung on the chest, equally as a crown is placed on her brushed-out hair.’ Comparable to this traditional elaborate crown, which was initially used in the same Höks district in Halland province. The striking headgear includes metallic lace, glass pearls, a selection of colourful silk ribbons, and cut fabric pieces to hang down the back of the young woman. | The illustrated crown is undated but probably originating from the second half of the 18th century. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0052127. DigitaltMuseum).Hörberg continues with his observations of the wedding preparations in the local area: ‘A braid of silver or gilding is placed around the sweater hem, one around the waist, or another belt borrowed from good friends. In other places, some brides are dressed by the priest’s wife in the parish, who borrows the bride some of her fine clothes. At my arrival [in 1758], it was also customary here, but due to that, I got tired of all wedding voluptuousness; my wife gave up this earning, which only is a few ells of linen for the one who dress [the bride] and the same to the spokesperson. The groom has by now [the 1790s] blue woollen garments, yellow chamois leather trousers and boots, loose cuffs with red edgings on the sleeves, etc.’

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Osbeck’s journal & biography. Vol. Seven: pp. 15-226 & Vol. Eight: pp. 50-53).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 108-124. See Pehr Osbeck’s chapter for more information about his textile observations).

- Osbeck, Pehr, Dagbok öfwer en Ostindisk Resa åren 1750, 1751, 1752. Publ. 1757.

- Osbeck, Pehr, Anledningar Til Nyttig Upmärksamhet under Chinesiska Resor. Inträdes-Tal i Kongl. Vetenskaps Academien, 1758.

- Osbeck, Pehr, Utkast til beskrifning öfver Laholms Prosteri 1796, Lund [facsimile] 1922. (Quotes in translation: pp. 76-77 & 83-84).

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden (DigitaltMuseum: Provenance information about the blue coat, red jacket and crown illustrated in this essay).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE