ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

MANUFACTURING & HOME WEAVING

– a Study of Woollen Textiles from 1700 to 1750

Local manufacturing of woollens, home weaving, imports of cloth, purchases from pedlars or coastal seafaring trade were all possible options for the citizens of Malmö in the early 18th century. Besides the trade, this study focuses on the weaving of broadcloth and similar qualities by locally active masters, journeymen and apprentices. A visit to the Swedish National Archive a few years ago also gave new pieces of information regarding which types of cloth the professional weavers and dyers produced in Malmö 1744. The increased weaving of decorative interior textiles – in farming communities within this area of southernmost Sweden – will additionally illustrate this essay.

Early 18th century portraits of ordinary people in the Nordic area is quite unusual. This painting dating 1701 is a rare example – purchased by Kulturen in Lund 1904 from the Malmö merchant Eugen Wingårdh. Maybe the farmers lived in the same area 200 years earlier. All three men are depicted in warm woollen clothes of wadmal or broadcloth, whilst a linen tablecloth covered the table. Oil on canvas, attributed to Magnus Jürgens. (Courtesy of: Kulturen in Lund, KM 14554, Creative Commons).

Early 18th century portraits of ordinary people in the Nordic area is quite unusual. This painting dating 1701 is a rare example – purchased by Kulturen in Lund 1904 from the Malmö merchant Eugen Wingårdh. Maybe the farmers lived in the same area 200 years earlier. All three men are depicted in warm woollen clothes of wadmal or broadcloth, whilst a linen tablecloth covered the table. Oil on canvas, attributed to Magnus Jürgens. (Courtesy of: Kulturen in Lund, KM 14554, Creative Commons).Wars, high taxes and epidemics made daily life difficult and obstructed trade in Malmö during the first two decades of the 18th century. Even if many people died in widespread illnesses during the winter of 1709/1710 and 800 to 1,000 individuals lost their lives in the plague in 1712, it is still possible to trace textile activities from several perspectives in local historical documents. For instance, giving evidence for that goods were offered for sale by the itinerant pedlars from Västergötland as well as various other cloths could be found in small-ware shops at the marketplace Stortorget in 1710.

The prolonged Great Northern War (1700–1721) also subdued all sorts of trading activity in periods; as a consequence, the ships preferred to avoid Öresund, and the Malmö merchants had their goods delivered to Trelleborg on the south coast instead. This affected, among others, the merchant Frantz Suell the Elder, who in 1717 imported printed calicoes and silks via Rostock on the Baltic Sea coast to be sold in his Malmö shop. Another transport route for textile wares to Malmö was the inland coastal trade, foremost from the former Danish areas Halland and Bohuslän. This merchandise primarily included linen and wadmal, which were basic assortments of textiles possible to produce in home environments. The demand was substantial for these types of fabric, used for clothes and interior furnishing alike.

![Fabric samples which originate from the woollen manufacturer Johan Cornelius Ledebur in Malmö, 1744 (Ledeburska Fabriquen). Despite the plastic film, these colourful samples demonstrate some of his workshop’s assortment of broadcloth in various weaving techniques and printed flannels. Riksarkivet [Swedish National Archives], Stockholm. Photo: Viveka Hansen.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-ledeburska-malmocc88-664x653.jpg) Fabric samples which originate from the woollen manufacturer Johan Cornelius Ledebur in Malmö, 1744 (Ledeburska Fabriquen). Despite the plastic film, these colourful samples demonstrate some of his workshop’s assortment of broadcloth in various weaving techniques and printed flannels. Riksarkivet [Swedish National Archives], Stockholm. Photo: Viveka Hansen.

Fabric samples which originate from the woollen manufacturer Johan Cornelius Ledebur in Malmö, 1744 (Ledeburska Fabriquen). Despite the plastic film, these colourful samples demonstrate some of his workshop’s assortment of broadcloth in various weaving techniques and printed flannels. Riksarkivet [Swedish National Archives], Stockholm. Photo: Viveka Hansen.Sven T Kjellberg’s thorough research in the 1940s of the woollen manufacturers in 18th century Malmö (pp 647-95) also mentioned Johan Cornelius Ledebur, who in 1739 started his business together with Jöran Falkenblad and Jacob Hegardt. Their manufacturing included a wool area, weaving rooms and spaces for packing – staffed with 39 workers. Ledebur died as early as November 1743, even if his name still existed on the accounts of cloth samples the following year. It seems to have been challenging to find enough locally qualified weavers; the manufacturers, therefore, employed several Germans and Dutchmen as Kjellberg noted: ‘…the master Jacob Berendt and the journeymen Johan Berg and Jacob Meiding, sock weaver master Conrad Egidius Mejer and the wool specialist Christoffer Knebel.’

Woollen manufacturing was active as early as the 1680s (described in the previous essay of this series) and continued to be so during the whole period from 1700 to 1750. At times, with more than one establishment. Overall, the trade seemed to be very changeable: owners often stayed for short periods only, unsuitable choices of premises, poor profitability, difficulty finding the correct staff, as well as child labour and educational ambitions for an orphanage. Some years were, however, more optimistic, for instance, in 1709, when a substantial order from the cavalry regiment in Skåne included fabric for 2,000 coats. The early 1730s up to the 1750s was regarded as a flourishing period for the woollen trade in Malmö with a large number of employees from a wide selection of vocations – unskilled boys and workmen, carders, spinners, fullers to specialist dyers, master weavers, journeymen and apprentices.

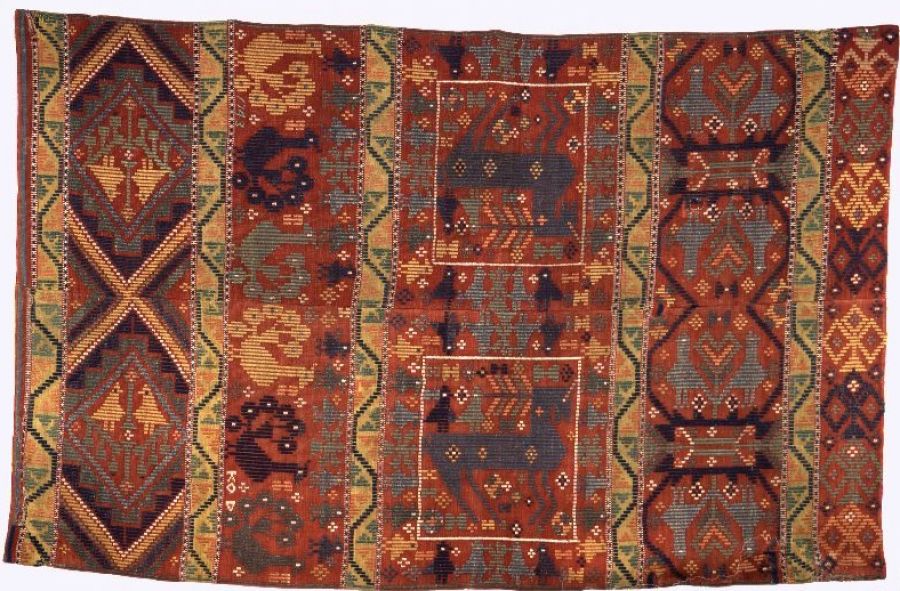

From the mid-18th century, the weaving of interior textiles also increased substantially in the countryside close to Malmö. See two examples of such skills and traditions on bedcovers below, woven for dowries, etc, used by daughters, mothers and other female individuals in well-to-do farming families.

This bedcover was woven in brocaded on the counted thread technique on a hemp warp and woollen weft, dated “1743” in chain stitching. Traditional in colour as well as in motifs with deers, peacocks, birds and trees of life. Woven in two identical pieces and stitched together with a middle seam, by an unknown woman – with the initials “KOD” – in a farming community close to Malmö. 200 cm x 127 cm, Bara district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM 029355, Creative Commons).

This bedcover was woven in brocaded on the counted thread technique on a hemp warp and woollen weft, dated “1743” in chain stitching. Traditional in colour as well as in motifs with deers, peacocks, birds and trees of life. Woven in two identical pieces and stitched together with a middle seam, by an unknown woman – with the initials “KOD” – in a farming community close to Malmö. 200 cm x 127 cm, Bara district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM 029355, Creative Commons). A close-up detail of another bedcover, dated a few years later in “1746” with the initials “KMD”, demonstrates that the skilled female weavers in the farming villages around Malmö often used the same type of motifs and choice of natural dyes for various weaving techniques. This time-consuming weave was made in a tapestry type “rölakan” on linen warp with woollen weft. 213 cm x 116 cm, Hököpinge village, Oxie district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM 002452, Creative Commons).

A close-up detail of another bedcover, dated a few years later in “1746” with the initials “KMD”, demonstrates that the skilled female weavers in the farming villages around Malmö often used the same type of motifs and choice of natural dyes for various weaving techniques. This time-consuming weave was made in a tapestry type “rölakan” on linen warp with woollen weft. 213 cm x 116 cm, Hököpinge village, Oxie district, Skåne, Sweden. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, MM 002452, Creative Commons).Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. Quotes are translated from Swedish to English. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen pp. 23-91, 1999.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943.

- Riksarkivet [Swedish National Archives], Stockholm, Sweden (Kommerskollegium. Kammarkontoret. “Industrivävnadsprover A-Ö”. Study of textile sample book from 1744).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE