ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

MENDING AND STORING CLOTHES

– Traditions in Whitby: 1700 to 1900

Patching and mending was an everyday occupation that could considerably lengthen the life of garments at a time when textiles and ready-made clothes were expensive to buy. However, patched and repaired clothes are seldom found in museum collections since clothes in this condition usually ended up recycled as rags by later generations of the family, if not by the owner herself. Nor was it at all likely that, even if it did survive, any repaired garment would have been presented to a museum. An in-depth study of local primary sources originating from the Whitby area – like photographs, preserved garments, embroidered samplers, newspaper adverts and sewing tools gives some ideas about these traditions. Whilst probate inventories reveal informative details about how clothes and linen were stored during the 18th century.

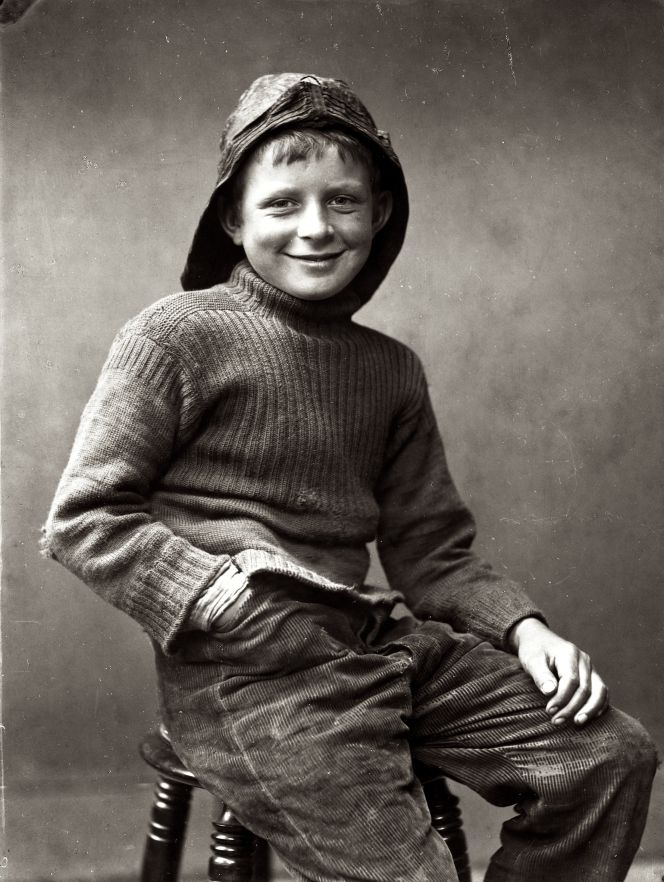

“Fisher Boy”, photographed in about 1890, revealed that the woollen knitted sweater had been heavily worn on the chest (some visible darning) and elbows. Several of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s photographs are evidence of ganseys often worn as everyday clothes, even when they show considerable wear-and-tear or have large holes. Warmth and comfort always came first, but even a tiny hole in a knitted garment can soon become big if not quickly darned. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 24-33E).

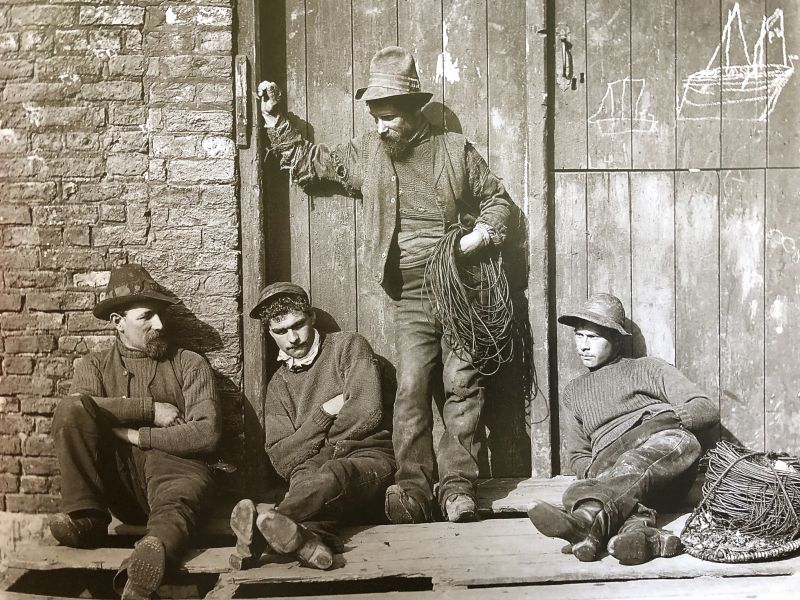

“Fisher Boy”, photographed in about 1890, revealed that the woollen knitted sweater had been heavily worn on the chest (some visible darning) and elbows. Several of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s photographs are evidence of ganseys often worn as everyday clothes, even when they show considerable wear-and-tear or have large holes. Warmth and comfort always came first, but even a tiny hole in a knitted garment can soon become big if not quickly darned. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 24-33E).  Daily wear and tear, together with various darning, is even more evident in this portrait by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe dated around 1900 – of four Whitby fishermen wearing their working garments. In particular visible on the elbows of their knitted woollen ganseys. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 4-34).

Daily wear and tear, together with various darning, is even more evident in this portrait by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe dated around 1900 – of four Whitby fishermen wearing their working garments. In particular visible on the elbows of their knitted woollen ganseys. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, Sutcliffe, 4-34).Advertisements in the weekly newspaper Whitby Gazette during the years 1855-1900 also show that buying clothes was an important form of investment. This fact accounts for why people took great care of their clothes, using them repeatedly and remaking them whenever possible. It was the same in middle-class and upper-class homes where a cast-off garment could either be passed on to servants of the same size, let out or taken in if it no longer fitted, or altered to fit children. However, it is rare to find any advertising or notices about darning, patching or repairing clothes, probably because these were occupations done by mothers, daughters or servants in the home environment. Draper’s shops and other establishments selling clothes particularly emphasised ‘good quality’ or ‘best quality’ or ‘hard wearing’ in adverts, so darning etc., may not have been seen as positive attributes. One of the few exceptions was the advertiser George Kitching in 1865 being ‘Cleaner and Repairer of Furs, Muffs, Boas, &c.’

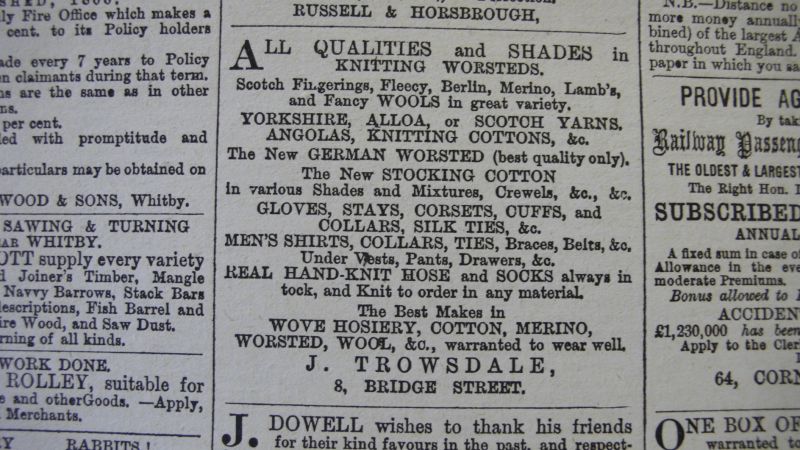

During the 1870s and 1880s, J. Trowsdale frequently advertised in the Whitby Gazette all kinds of yarn for knitting as well as ready-knitted stockings of various qualities from his stock in Bridge Street. The shop repeatedly emphasised that all knitted products were “warranted to ware well”, implying that the time-consuming darning was unnecessary for some time. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1880, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

During the 1870s and 1880s, J. Trowsdale frequently advertised in the Whitby Gazette all kinds of yarn for knitting as well as ready-knitted stockings of various qualities from his stock in Bridge Street. The shop repeatedly emphasised that all knitted products were “warranted to ware well”, implying that the time-consuming darning was unnecessary for some time. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1880, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Darning could also be practiced as an educational needlecraft in so-called “Darning samplers” or a variety of weave techniques constructed by the embroiderer with her needle, usually in cross-shaped or four-cornered patterns copying such techniques as tabby, 2/2 twill or diamond twill. This manner of working was in use from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th. There is one undated sampler of this type in the Whitby Museum collection, sewn by M. E. Bland at the age of 14, with rows of alphabetic letters sharing the space with three “darning” squares at the bottom of the sampler. To be able to “sew” in a variety of techniques was not only a good way of filling up the embroidery, but an essential learning process for a young girl doing it, since such skills could come in very useful for repairing a hole in a piece of twill clothing when a virtually invisible mend was needed.

However, in-depth research through the extensive collection of clothes in Whitby Museum has revealed only one mended item of clothing and one made from large scraps of cloth sewn together. Both were made for children in the Victorian period. No attempts to reproduce the techniques of woven fabric by darning, tabby, 2/2 twill or diamond twill have been found anywhere in the collection.

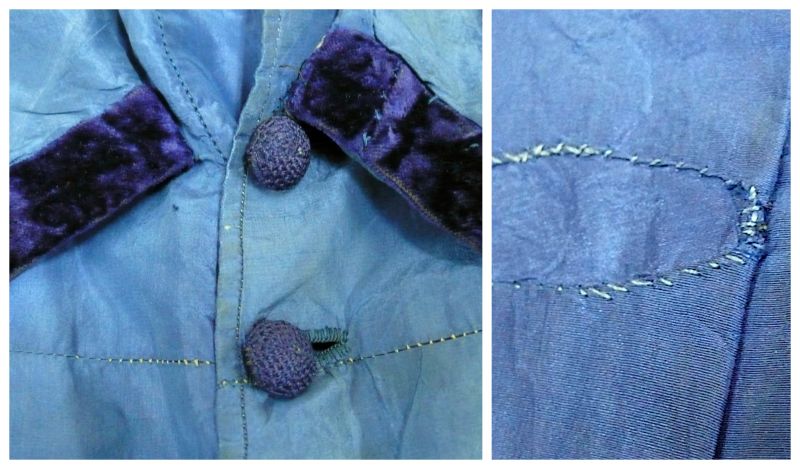

This well-made dress in blue silk fastening at the front with dark-blue buttons and a dark-blue velvet collar were intended for a girl of 6-8 years old. The upper part of the dress has been lined with unbleached linen, and the lower part with waxed tulle. As the illustration to the right shows, a hole in the fabric has been efficiently patched with a piece of the same silk fabric. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, 2006/42.15.). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This well-made dress in blue silk fastening at the front with dark-blue buttons and a dark-blue velvet collar were intended for a girl of 6-8 years old. The upper part of the dress has been lined with unbleached linen, and the lower part with waxed tulle. As the illustration to the right shows, a hole in the fabric has been efficiently patched with a piece of the same silk fabric. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, 2006/42.15.). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The second garment mentioned above was made from small pieces left over from other clothes, skilfully assembled into a little coat for a child of 2 or 3 years. The garment has been sewn from black silk and decorated with black fringes, entirely hand-sewn and lined with a cotton cloth. In the collection, it is otherwise common to find clothes that are torn or have been worn extensively, especially certain types of fragile silk that quickly disintegrate. Many factors have contributed to this: the way the clothes were treated when in use, how they were kept before they came to the museum, and how they have been treated, stored and exhibited since, while we should bear in mind that between more than hundred or sometimes almost two hundred years have passed since these clothes were last in use.

Looking further back, the probate inventories are a good source of information on the kind of furniture used for storing clothes and household linen in Whitby homes during the 18th century. In the first half of the century, chests were common; for example, the master mariner Richard Ward in 1705 owned ‘2 chests’ and the blacksmith Robert Patison in 1744 had ‘a chest’. The custom of keeping clothes and linen lying flat in a chest was a survival from the previous two centuries when it was the usual way of storing clothes. But during the 18th century, the ‘chest of drawers’ became increasingly common in many Whitby homes. This type of furniture had developed to keep pace with the changing fashion in clothes, as lighter-weight material that demanded greater care in storage began to be popular towards the end of the 17th century. Quite simply, delicate silks and satins could be destroyed if everything was piled indiscriminately into a large chest, so garments were folded carefully and increasingly placed in pull-out drawers together with underclothes and accessories. Such a chest of drawers was equally suitable for storing bedclothes, tablecloths and napkins. Furniture of this kind was already well established in Whitby by the beginning of the 18th century when many homes contained two or three chests of drawers, as can be seen from the inventory of the master mariner Francis Smith in January 1702. He had two pieces of furniture of this kind kept in different rooms in his home, and the inventory lists the contents of one of these: ‘In the chest of drawers in the Chamber over the Dining Room 12 pairs of sheets, 5 dozen of the diaper, huckaback and damask napkins, 6 table cloths and 18 pillow beers, 6 window curtains and several other small things’ to a value of £13 3s 4d. It was the textiles rather than the furniture that caused the high valuation, as can be seen from the case of the mariner George Jackson in 1720 when ‘1 chest of drawers’ was valued at only 10 shillings. Similarly, fifty years later, in 1771, the mariner John Gibson owned ‘1 chest of drawers’ worth 12 shillings. Another way textiles could be stored – though only recorded at the beginning of the century – was in a trunk, as in the case of the widow Alice Nellist who in June 1710 possessed ‘An old trunk, linen, 2 cradle cloths’ valued at £5.

In conclusion, the overall storage of garments continued to be stored lying flat throughout most of the 19th century in various chests of drawers, large cupboard wardrobes and an occasional old chest. Clothes hangers were invented around 1870, giving people their first chance to hang up clothes in a wardrobe (if not on a hook). This is a rare survivor, dated to around the year 1900, and evidently from the Whitby tailor ‘G.L. Watson & Sons Tailors Whitby’, an establishment located in Flowergate according to a 1901 directory. The 1901 census also gives further information on the 59-year-old George Watson, living in John Street, where several sons assisted him; the younger Watsons were all tailor cutters: William (31), Thomas (27) and Joseph (21). This clothes hanger is contemporary with the written local sources – probably once part of the sale when a customer had a jacket or suit made up at the tailors. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, not catalogued at time of research). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

In conclusion, the overall storage of garments continued to be stored lying flat throughout most of the 19th century in various chests of drawers, large cupboard wardrobes and an occasional old chest. Clothes hangers were invented around 1870, giving people their first chance to hang up clothes in a wardrobe (if not on a hook). This is a rare survivor, dated to around the year 1900, and evidently from the Whitby tailor ‘G.L. Watson & Sons Tailors Whitby’, an establishment located in Flowergate according to a 1901 directory. The 1901 census also gives further information on the 59-year-old George Watson, living in John Street, where several sons assisted him; the younger Watsons were all tailor cutters: William (31), Thomas (27) and Joseph (21). This clothes hanger is contemporary with the written local sources – probably once part of the sale when a customer had a jacket or suit made up at the tailors. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, not catalogued at time of research). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Sources:

- Cook, W. J. & Co., Whitby and District Directory, Whitby 1901.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 40, 277, 281, 309, 321 & 337).

- Vickers, Noreen, A Yorkshire town of the 18th century, Whitby 1986.

- Whitby Gazette, 1855-1900 (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive: study of original papers).

- Whitby Museum (Whitby Lit. & Phil.), England. Costume, Social History and Photographic Collections and Library & Archive (garments, tools, clothes-hangers, newspapers and photographs).

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library, England. (Census 1901, microfilm).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE